Cast your mind back to 1994, when Sony was preparing to launch its first PlayStation console. The company had a less-than-enviable reputation in the world of video games; its Sony Imagesoft publishing arm had spewed out largely risible titles such as Last Action Hero and Cliffhanger, and many within the industry were still dining out on the fact that Sony had been jilted by Nintendo, with the latter famously backing out of its agreement with the former to produce a CD-ROM drive for the SNES (the genesis of the entire PlayStation project). With no genuine video game credentials to its name, how could Sony possibly hope to challenge the might of Nintendo and Sega – both of which had talented in-house teams capable of producing hits such as Super Mario World, Sonic, Daytona, Metroid and Star Fox?

The answer, as time would tell, was third-party support. Sony made the PlayStation the hottest system in town by giving it powerful specifications, making it relatively easy to develop for and reducing the licence cost per disc, which meant that publishers could sell games for significantly less than they could with cartridge software whilst still maintaining those all-important profit margins. Sony's strategy worked brilliantly, and within its first year, the PlayStation established itself as the market leader all over the globe – but, you could argue, one company stood apart from the rest when it came to assisting in this meteoric rise to power: Namco.

Namco's Rise To Power

Founded in 1955 as Nakamura Seisakusho, Namco would become one of the gaming industry's leading lights thanks to a string of arcade hits like Galaxian, Pac-Man, Galaga and Xevious. Like so many of its competitors, Namco bolstered its position in the '80s by aggressively backing Nintendo's Famicom console, known as the NES in the west. However, from the very beginning, Namco's relationship with Nintendo was a tense one, reflecting the battle of wits that Namco founder Masaya Nakamura waged with Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi.

Nakamura got his son-in-law, Shigeichi Ishimura, to put together a team to reverse-engineer the Famicom hardware and create a port of Galaxian – a port that was so good that it was presented to Nintendo along with the message that Namco intended to manufacture and release it without Nintendo's consent, a threat that enabled Namco to sign a five-year contract with Nintendo that was weighed heavily in its favour, allowing the company to manufacturer its own Famicom carts rather than order them from Nintendo.

However, the company's perceived arrogance would come back to bite it; Nintendo created a strict licencing strategy on the back of this event to ensure no other company would ever get the same treatment, and when the five-year deal expired – a deal which had given Namco several million-selling hits and filled its coffers considerably – Yamauchi was less inclined to bow to Nakamura's pressure and told Namco that it would have to sign the same deal as every other publisher.

Although Namco would sign the new agreement anyway – it wasn't going to turn its back on the cash cow that was the Famicom – Nakamura was reportedly furious and quickly made it company policy to explore other platforms, including the NEC PC Engine and Sega Mega Drive. Namco even briefly toyed with the idea of leveraging its arcade experience to produce its own console, a venture that ultimately never happened. However, the company was still very much aware that home hardware was its crucial market, and when Sony announced the PlayStation in 1994, it quickly signed up as the first third-party supporter of the platform.

Racing On The Ridge

Every console needs a killer app at launch – a title which demonstrates precisely why consumers should invest in it. For the PlayStation, that game was Ridge Racer, a port of the 1993 arcade racing title of the same name. Reportedly produced in six months, the PlayStation conversion was nothing short of a revelation; while it wasn't quite arcade perfect, it was a close enough approximation of the coin-op to cause jaws to drop all over the world.

Namco's relationship with Sony would go beyond being just a third-party ally, however; Tekken, seen as the PlayStation's answer to Sega's massively popular Virtua Fighter, was produced using the System 11 arcade hardware – hardware based on the PlayStation architecture. This ensured a smooth conversion, and while debate still rages on whether or not Namco's brawler is a true match for Virtua Fighter, it chalked up another success for Sony and Namco – and yet another smash-hit in commercial terms. The ball had started rolling on one of the most productive periods in Namco's history.

Steve Jarratt was the launch editor of the UK's EDGE magazine and covered the early months of the PlayStation story before launching the UK's Official PlayStation Magazine, which would accompany the UK release of the machine. As such, he's perfectly placed to discuss why the collaboration between Sony and Namco was so significant.

With Ridge Racer, the phrase ‘arcade perfect’ was constantly bandied about the office. It’s blatantly untrue of course, but it didn’t matter: it felt like a genuine gaming revelation, which you could only experience on PlayStation

"I think getting any major third-party publisher/developer on board at launch is key for the initial impact of a new console," he tells Time Extension. "The PlayStation launch line-up was pretty solid by most standards, but take away Ridge Racer and Air Combat, and it’s definitely less appealing. With a new machine, there are always one or two games that cause the biggest amount of excitement, and back then, working at Future Publishing, Ridge Racer was definitely top of the pile (closely followed by Battle Arena Toshinden). With Ridge Racer, the phrase ‘arcade perfect’ was constantly bandied about the office. It’s blatantly untrue of course, but it didn’t matter: we all believed we were playing a near-identical version of the coin-op, and at the time, it felt like a genuine gaming revelation, which you could only experience on PlayStation. That’s the kind of influence and mind share that console manufacturers dream about."

Paul Davies, who was working Future Publishing rival EMAP Images at the time and would become CVG editor as the PlayStation reached its commercial zenith, is in agreement. "From launch, PlayStation became the Namco console. Ridge Racer was the main reason to buy PlayStation in December 1994, and then Tekken in early 1995. Both were so close to the coin-op originals that it felt like the truest arcade experience at home, showcasing what PlayStation was capable of – which was stunning. At the time, Sega had Virtua Fighter for Saturn, which played superbly well but looked poor in comparison. With Ridge Racer, Namco included secrets to unlock, adding huge replay value. The near-simultaneous launch of Tekken in arcades and on console was unheard of. That partnership between Sony and Namco was simply a killer tactic. If you think in terms of Tekken being the Fortnite of its day – which I believe it was – that it was exclusive to PlayStation was huge."

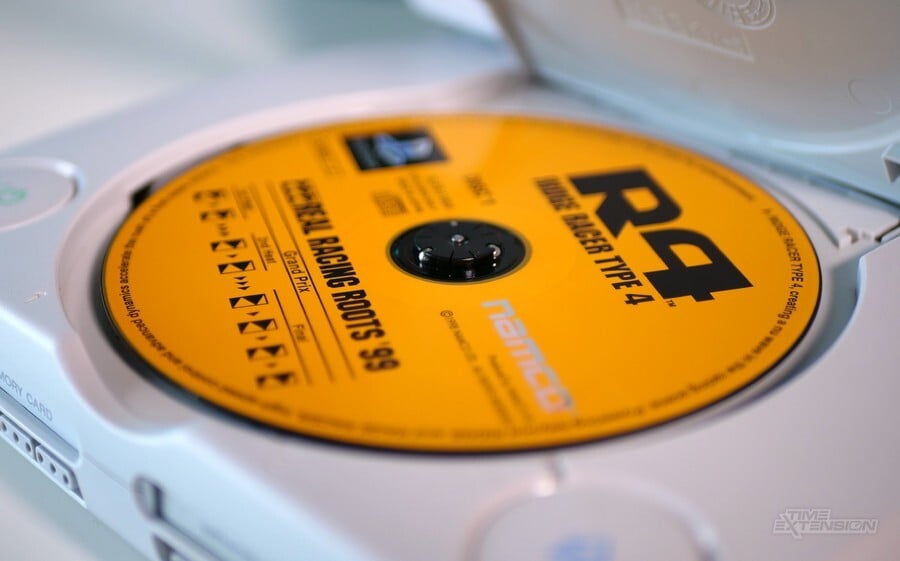

While Sony would attract other big-name allies like Square, Capcom, Eidos and Enix, the almost exclusive association with Namco endured throughout the machine's life, thanks to a seemingly unending stream of AAA titles – all of which couldn't be found on any other system. The relationship between the two firms was so tight that Sony itself issued advertisements for Namco's games, promoting them with the same vigour one would expect of first-party titles. While there were some duds thrown into the mix – Cybersled was an early misstep – the next few years were populated by a string of solid-gold PlayStation classics from Namco. Ridge Racer Revolution, Rage Racer, Time Crisis, Tekken 2, Soul Blade, Ridge Racer Type 4, Ace Combat 2, Point Blank... the production line seemed to go on forever, and the Namco name on the cover was as sure a sign as any that what you were getting was a quality product.

"Namco’s support over the following years provided a constant stream of varied and high-quality games," says Jarratt. "During this period, I think there was a certain gloss to Namco’s games; the feeling that you wouldn’t go far wrong with the Namco name on the box. I think the PlayStation would still have succeeded without Namco’s support, but it’s undeniable that it got there faster with Namco’s franchises on board. Its presence and heritage in the arcades brought a certain cachet, and it clearly had some top programmers who wrung every bit of power from Sony’s hardware. And once they got to grips with the machine, Namco’s sequels were revered as among the best games of the era."

Capturing The Zeitgeist

While Jarratt and Davies were tasked with covering these exceptional releases from a professional standpoint, they're both happy to admit they were as invested and enraptured by Namco's output as their readers were. "My two abiding memories of that period are spending hours upon hours attempting (and finally succeeding) to beat the black car in Ridge Racer, and daring to put Pac-Man on the cover of issue 5 of the Official UK PlayStation magazine," remembers Jarratt. "That was for the release of NAMCO Museum Vol. 1, which provided a brilliant virtual gallery of Namco’s classic coin-ops."

"My first Christmas at my folks’ with Ridge Racer in 1994 is my fondest memory, even though I was actually working on a Nintendo mag at the time," recalls Davies, "I got to play early pre-release versions of Ridge Racer Revolution with no scenery, only roads, and then later got to see these details added – that was amazing and I still smile at the memory. Tekken 3 was the most amazing arcade-home conversion, with an arranged Big Beats OST that I duly recorded onto Mini-Disc. I don’t know how I stopped myself from getting a tattoo like Jin Kazama. I bought every issue of EDGE the month it came out with the different covers."

The youth culture of mid-'90s Japan was so joyful, and Namco’s distinctive brand tapped into that

Indeed, Davies feels that Namco captured the zeitgeist of the period in very much the same way that western-made titles like WipEout and Tomb Raider did – but with a Japanese flair. "The youth culture of mid-'90s Japan was so joyful, and Namco’s distinctive brand tapped into that. This was a worldwide thing, though. The 1990s had great energy, and Namco exuded it. Namco was building on decades of development and vibrant marketing experience from the arcade business. It was no newcomer in that respect; it was already a class act. Namco knew its audience, teaming up with J-Pop artists Deen for the OST on Tales of Destiny, perfectly aligned in terms of brand image. It made Big Beats the sound of Tekken, unmistakable in the arcade. The development teams were authentically enthusiastic."

While it seems somewhat passé now in an era where corporations create make-believe 'VTubers' to hawk their products, Namco's creation of a 'virtual idol' for its Ridge Racer series typifies how committed the company was to giving its titles that extra dimension. "It probably wouldn’t be as well-received now, but ‘race queen’ Reiko Nagase glamourised what might’ve been regarded as ‘yet another car game’," says Davies. "Namco made a great effort to infuse its video game heroes with style and/or anime cutesy appeal. CG sequences for Reiko to usher in each new Ridge Racer were always stylish/sexy/thrilling, not to mention cutting edge."

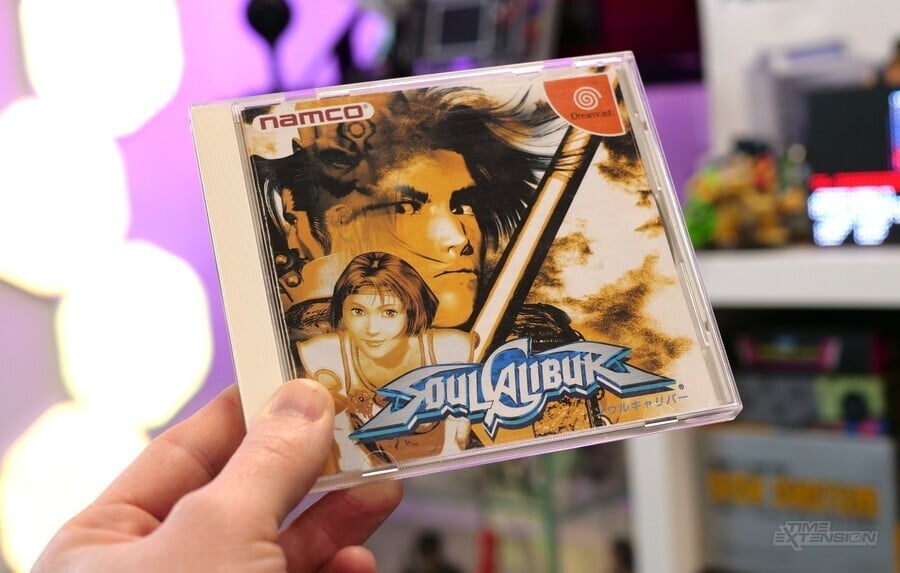

No Longer Exclusive

It speaks volumes that when Sega launched its make-or-break Dreamcast console, enlisting Namco to create SoulCalibur was seen as a major coup; however, the company remained mostly loyal to the PlayStation line, continuing to support Sony with key titles like Ridge Racer V and Tekken Tag Tournament. Still, the generation-long love-in between Sony and Namco was slowly coming to an end, with the latter beginning to spread its wings and produce titles for PS2 rivals GameCube and Xbox during that hardware generation.

Today, the familiar red Namco logo has been replaced by one which displays two brands: Bandai and Namco, thanks to the fact that the two companies merged in 2005. The company has also shifted into publishing, handling the likes of FromSofware's Elden Ring and Dark Souls, Little Nightmares II and as well as Supermassive's Dark Pictures series. Key properties from the '90s remain in active service, with Tekken and Ace Combat still getting regular sequels, but some would still argue that the company's hit rate is nowhere near as prolific as it was during the PlayStation 1 era – and, of course, the company is no longer committed to a single format in the same way, as it has branched out onto both Nintendo and Microsoft's systems. That coveted feeling of exclusivity no longer exists.

The Bandai Namco of today is arguably stronger and has a wider reach and influence than it did all those years ago, but that doesn't take away from the fact that the '90s was a truly magical time to be a PlayStation owner – and a gamer in general. "The magazine team I worked with in ’95 were Sega nutters – and for a good reason, I should add," concludes Davies. "But public interest in PlayStation and the quality of those early Namco games made us converts. There was the same excitement around the big Namco games as any band I ever got into. You could feel it in your jaw, like sour sweets."