Mark Cerny is a true veteran of the games industry. His name might be familiar to modern gamers due to the fact that he's worked as lead architect on several of Sony's consoles – and has even had input into some of the company's major software releases, such as Knack, The Last Guardian, Marvel's Spider-Man and Death Stranding – but his career stretches back to the very early years of the games industry.

Cerny joined Atari in 1982 and designed and co-programmed the coin-op title Marble Madness. He has also worked at Crystal Dynamics and Universal Interactive Studios during his illustrious career, but, in an interview conducted for Bitmap Books' Master System: The Visual Compendium, this writer was lucky enough to sit down with the great man to discuss his tenure with Sega – during which he worked on the groundbreaking Master System 'SegaScope 3-D' Glasses, gave Michael Jackson a studio tour and established Sega Technical Institute, the team which would create Sonic the Hedgehog 2.

Cerny grew up at a time when video games were only just becoming a viable medium of entertainment and, by his own admission, wasn't all that enamoured with what he saw, at least initially. "The first video game I ever played was Pong, or some variant of it," he says. "I wasn’t all that interested in it, but when I was in High School a few years later, a friend came to me and said, 'Wow, I just played this most amazing game', and he described this thing with soldiers getting closer and closer and shooting at you, and you have to hide behind bunkers and poke your head out and shoot back. What he was talking about was, of course, Space Invaders; starting with that, I became a huge fan of arcade games."

Around the same time, Cerny became interested in the potential of computers and programming – so much so that this became his other major hobby during his formative years. "My brother and I were trying to code up a full-blown 3D action RPG with punch card technology while we were in high school. Not a particularly realistic dream, of course! A couple of years later, I realised that maybe I could turn my two hobbies, which were playing arcade games and programming, into a job."

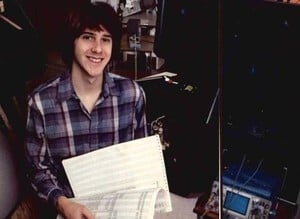

Cerny's route into the games industry happened in a rather unusual fashion; his prowess with a joystick was such that he was interviewed for a book about video game strategy – a true novelty back in the early '80s – and this led to a vital connection being made at Atari. "The author of the book knew all sorts of people in the gaming industry because he had not only been interviewing players about the strategies that they were taking, but he had also been interviewing game creators. He very kindly offered to approach video game publishers on my behalf; he suggested either Activision or Atari. I liked the graphics of the arcade games, so he contacted Atari's vice president, and I got an interview. I was 17 at the time, and somehow, I got in the door and got a job as a programmer – which also meant artist and game designer, as that’s what we all were at Atari."

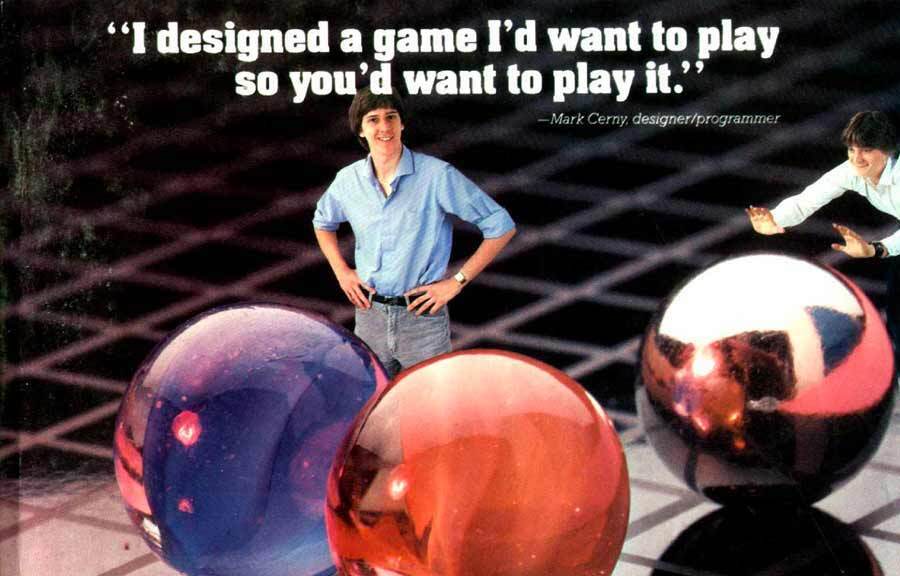

His first game was put out on location test but failed to generate interest, while his second outing was Major Havoc, a project he didn't join until it was close to completion. It would be Cerny's third game at Atari, Marble Madness, that would truly put him on the map. "Marble Madness was my baby. I had some fantastic help from Bob Flanagan – who was the programmer on the title, as well as a fantastic artist and sound designer." An instant success in arcades, Marble Madness would be ported to a wide range of domestic systems, including the NES, Amiga, Mega Drive / Genesis and (much later) Game Boy Advance.

Such was Cerny's success with the game that he decided to go indie in 1985, at the tender age of 20. "I thought I’d start my own company and make arcade games and license them for manufacture," he recalls. His first client was Sega, for whom he created an arcade title. "It turned out to be much harder than I thought once I was doing everything and not just my little piece of the game. The arcade game didn't go particularly well, but Sega was very forgiving, and after a bit over a year of me flailing around trying to make a game, Sega president Hayao Nakayama invited me over to Tokyo."

While Sega's coin-op division was flying high, its home console business was less buoyant, and Cerny was brought in to help out in that field. When he arrived at Sega, the company's SG-1000 – which launched on the same day in 1983 as the Famicom in Japan – had failed to make a dent in the Japanese market, while its successor, the Sega Mark III, experienced similar difficulties in its homeland. Sega knew that the global market was key to its success, and decided to rebrand the Mark III as the Master System for international markets. Cerny was tasked with creating software for the console.

"Nakayama had this idea that Nintendo had 40 games that were available for the Famicom – or NES as it was known in the west – and if we had more games, then we could be more successful than they would be," Cerny recalls. "So his target was to have 80 games for the console. The difficulty was that only a few of these games had a good fun factor. Eventually, some wonderful games were made for the Master System, but in that first year, it was pretty tough going. If I remember, the two games that stood out in the early days were Fantasy Zone and Choplifter."

Ironically, given that Sega's strength was its arcade output, Cerny points out that in the early days, the company was focused on generating original content rather than leveraging its the brand power of its coin- op titles. "That first batch of games was almost all original titles, not arcade conversions," he says. Later, when the company began converting the likes of Hang-On, Out Run and After Burner to the console, Cerny felt unsure that the hardware was up to the challenge of replicating a cutting-edge arcade system in the home. "But it turned out there was a magician in the group, and his name was Yuji Naka," Cerny says. Naka has recently fallen on hard times, but back then, he was earning a reputation as being one of Sega's superstars. "He sat a few desks over from me, and he somehow was able to do it," remembers Cerny. "So I think the Master System got some traction on the basis of those incredible conversions, and then, over time, it got some traction thanks to its original titles, as well."

So, what was it like being one of the only western staffers at Sega of Japan? Cerny explains that it came with both good and bad points. "In terms of people actually involved in making the games, I was one of perhaps two foreigners at Sega out of hundreds of people – and I barely knew the other guy! I either talked to people who could speak a little bit of English or didn't talk at all. On the one side, that’s very focusing in terms of getting work done, but on the other hand, it's a little tough."

Cerny's first project at Sega was a title called Shooting Gallery; a fairly straightforward arcade-style game which leveraged the console's 'light phaser'. "These were very quick games to make," Cerny says. "The idea was it would be three months of work, with one artist and one programmer." However, his next project would combine both software and hardware, something that Cerny has done during his recent career, via his work on Sony. "I'd gone and seen Captain EO, which was a short 3D movie starring Michael Jackson. It was showing at Disneyland in Tokyo, which had just opened, and I thought it was quite inspirational. So I lobbied management to create 3D glasses for the Master System. I did the tech demo, which was sort of the Pong-style game we showed at CES, and then I did the bundled title, which was Missile Defense 3-D."

At any other company, a young 'gaijin' staffer suggesting that an entirely new piece of hardware be created to facilitate their vision might have been ignored, but as Cerny explains, he was able to make that leap at Sega. "It wasn’t that hard to do, because Sega – through its arcade division – was used to creating many pieces of hardware each year. Also, president Nakayama was looking for leverage in the battle with Nintendo, and the idea that we could have 3D games was very appealing to him. At the same time, he didn't know if this was a gimmick, or going to be a real part of gaming – and I think you can see that debate continuing thirty-something years later! The glasses used shutter technology, and games ran at 30Hz – if you were in Europe, they ran at 25Hz. The big challenge was finding a vendor who could cheaply provide two reasonably large liquid crystal shutters."

Nintendo would create its own pair of 3D glasses in 1987, but these were only ever available in Japan, whereas Sega's glasses were given a global release. According to Cerny, the Sega Scope 3-D Glasses sold 300,000 pairs – hardly the kind of figure that would move the needle in modern gaming, but context is important here. "I don’t know if you qualify that a success or a failure, but for a company that had only had a 4 percent market share in North America – compared to Nintendo's 94 percent – that’s a pretty good number, I think," Cerny says.

Cerny also worked on two notable ports for Sega's 8-bit console, Shanghai and California Games. The former presented him with one of the trickiest technical challenges of his career up to that point. "I did Shanghai because I thought it would be a quick project," he admits.

"I thought I could code it up in six weeks. I ended up taking three months! Interestingly, doing intricate graphics for piles of Mahjong pieces with shadows, that wasn't the hardest thing. The hardest thing was all of the various UI screens that needed to be included in the title to let you start a game, finish a game and save a game – all of those things. But that was a lot of fun, and it was a real technical challenge, because the Master System didn't have enough RAM to do a full-screen bitmap, so we had to use all kinds of tricks. For example, we'd have an 8x8 pixel stamp, and we'd replicate it across the screen. Shanghai’s graphics really did need some sort of bitmap technology, particularly if you had shadows there. So, what I had to do was display the top half of the screen, copy more pre-created graphics from RAM into the display buffer to get the bottom half of the screen displayed, and then repeat that to get the top half of the screen back in display memory. So behind the scenes, I was basically 'racing the beam' of the TV set in order to get those images displayed. That’s the sort of thing that every Atari 2600 title would do, but it was a bit more unusual to be doing it on the Master System all those years later."

California Games would be, in Cerny's words, a much larger project. "I think it took me five months, and in this case, for the first time, I had a dedicated designer. The designer’s role was to go and research what California Games was, what was in each of those mini-games, and then work with the artist to create the graphics that would replicate the game on the Master System. The funny thing about this was my designer spoke no English, and I spoke no Japanese at the time! He’d come by with a notebook where he’d use a glue stick to glue down various pieces of artwork that I needed to include in the game. He'd point to them, and make sort of picture with his hands!"

Interestingly, prior to our interview, Cerny claimed he was unaware that the Master System was so successful in Europe, where it outsold the NES – a complete reversal of its fortunes in North America and Japan, where Nintendo was utterly dominant. However, this isn't all that surprising, as towards the close of the 1980s, Cerny's attention would have been focused on Sega's next console: the 16-bit Mega Drive / Genesis, which launched in Japan in 1988. Sadly, he wasn't let loose on making games for the system immediately.

"It was nice to be playing around with quite a bit more power, but my first task for that console was to do networking software," Cerny recalls. "They made a modem because the publisher Sunsoft wanted to use it for head-to-head online baseball gameplay. They assigned me to do something interesting with the modem, and I said how about a game service where you could download games each month and play them as a subscriber – a bit like Netflix today. I think that was perhaps a little bit before its time! I did some of the underlying technology, again proof of concept stuff, just like with the 3D glasses. There were about maybe twenty games that were made for this service, but the subscriber count never went above the thousands."

It was around this point that Cerny got to meet the late Michael Jackson, arguably one of the most famous people on the planet at that time. Jackson – who would collaborate with Sega on a Moonwalker video game, compose music for Sonic 3 and star in an arcade title which was recently unearthed at a car boot sale in the UK – was a seasoned gamer and owned many arcade cabinets. When he paid a visit to Sega's Japanese HQ, it caused a predictable degree of pandemonium.

"He was a massive star in Japan at the time," remembers Cerny. "When people learned that he was coming to Sega, the building was surrounded by a mob of fans, several feet deep. It was like a scene from a zombie movie! We had to make a human wall around him to give him some privacy. Strangely, I ended up being the tour guide because I had the best English of anybody in the company! We gave him a complete tour. We started with the consumer games and took him around the lab. I believe we showed him the 3D stuff at the time, and at the end of it, we took him down to the first-floor lobby where we had all of the big arcade games – most of which were, of course, Yu Suzuki masterpieces. When we got down to the lobby to show him these arcade games, people outside were running at full tilt from all directions and would press up against the glass to get a look at this superstar."

Meeting a celebrity like Jackson was quite a perk, but Cerny was getting homesick and wanted to plot a return to North America, having been in Japan for over three years. He saw this as a chance to help Sega expand in that region. "There wasn’t a group making games for Sega in the US at that time, so we decided that we would transplant part of the Tokyo operation to the States; I returned to the US and started the Sega Technical Institute."

Before he left Japan, however, Cerny served as an intermediary between Sega's Japanese office and its North American one when it came to nailing down the design of Sonic, the new mascot which, it was hoped, would be able to challenge Nintendo's Mario. "I met with the team in Tokyo; this was at the time when Sonic was a little bit more 'rubbery' – he was a little bit more Disney-influenced," Cerny recalls. "They had done some sketches for Sonic and some for possible enemies; they had something that looked a bit like Bart Simpson. I bundled it all up, and sent it to the States to let them know that the star team was thinking of having this hedgehog as their lead character; I even made colour copies. Can you imagine how hard it was to make colour copies in 1990? I just wanted to make sure that they had as much information as possible."

It's remarkable to hear what happened next – in short, nothing happened. "There was no response," reveals Cerny. "When I finally asked, I was told that it was unsalvageable; that the character design was so bad, there were no comments that they could make that would help turn it into something saleable. What I heard was that they were going to be launching a project to 'educate' Sega of Japan about what good characters looked like. They were either very inspired by – or were going to be bringing in – Will Vinton, who, amongst other things, was famous for creating the California Raisins commercial. This was to show Sega of Japan how characters really needed to be designed. Of course, the game came out, we had a price drop on the hardware within the space of one or two months, and our sales went up by a factor of five. That was the end of any conversation about how bad a character Sonic the Hedgehog was!"

Two of those bold moves – the price drop and the Sonic bundle – were instigated by Sega boss Tom Kalinske, who took over from Michael Katz in the middle of 1990. "Tom was fantastic," Cerny says. "He was really charismatic, he understood games, and he understood advertising – and yes, he had a tremendous amount to do with the success in the States. He decided to drop the price of the Genesis and bundle Sonic with the system – that was a critical moment, but a hard one to sell. He really had to sell Tokyo management on that."

Cerny's vision for his new US-based Sega studio was to fuse Japanese expertise with western skills and create some of the best games the Mega Drive / Genesis had seen. Early on, there were a few roadblocks, however. "The plan was that a dozen veterans would get 'genius' visas, the kind of visas that Yuji Naka ultimately got as a future hall of famer," he says.

"We applied for 12 veterans to come over; you had to say that they had made 'unparalleled contributions' that were internationally recognised. I say veterans, but some of these guys only had two or three years experience of making games. Anyway, all the visas were rejected by the US embassy in Tokyo; in fact, Sega was blacklisted from even submitting applications for these visas for a while! So the US venture, which was supposed to be based on this core group of Japanese veterans, unfortunately, had to make do with whoever I could find in the US – the few people who were already there, or already had their visas."

Despite this setback, Cerny was still able to assemble a pretty solid team. "Shinobi designer Yutaka Sugano was already in the US, as was Hirokazu Yasuhara, who was the gameplay and level designer on Sonic the Hedgehog," he explains. "So, much of what we did was try to leverage the expertise of those people."

Just when it seemed like Cerny's hard work was paying off, another bombshell dropped. Amazingly, despite turning in the incredible Sonic the Hedgehog – the game which did much to transform Sega from an also-ran to a true home console heavyweight in North America – Naka wasn't happy with his employer and wanted out of the company. "As I was in the middle of setting up the company and getting out the first game – which was Dick Tracy – I heard that Yuji Naka was getting very disaffected with the operation in Tokyo," recounts Cerny. "He quit, and we managed to re-hire him as a project head and programmer at the Sega Technical Institute, which meant that we had two of the three key members of the original Sonic Team. Naoto Ohshima, the artist, stayed in Japan."

Sega Technical Institute's first title often gets overlooked and overshadowed by what came after. 1991's Dick Tracy was based on the Warren Beatty live-action adaptation from the previous year – a movie which Disney had high hopes for, but one that ultimately failed to bring in the same kind of box office return as 1989's Tim Burton-helmed Batman. As a result, the resultant video game has been forgotten somewhat, despite offering a fair amount of entertainment value. "We had two gameplay planes," Cerny explains. "The whole concept was you'd fight people in the foreground, and occasionally, you’d turn and aim into the background, and fight enemies there. So you would be very conscious of the two planes, which would scroll separately. It was quite the challenge."

Surprisingly, Disney didn't get too involved with the development, outside of making sure the game's visuals matched the film. "They wanted to make sure that the colours of the villains, their clothes, were the right colour. And they wanted to be sure that if we showed Dick Tracy, his face would look like Warren Beatty, who played Tracy in the movie. We’d send in our assets, and they’d touch them up. It was a great help, in fact. I can't recall any case in which there was something that we wanted to do with the gameplay that we couldn’t do because of the licence. They were great partners."

Indeed, it wasn't STI's relationship with Disney that was causing Cerny headaches at this moment in time, but rather the breakneck pace at which his new studio had pulled into existence. "The difficulty that we were having is that we were trying to start up a company and get a game out in five months! It ended up taking seven months and almost killing us. I think that caused us a lot of problems later because, in that critical first half-year, we should have been slowly bringing people into the Sega way of thinking and working, but instead, what we were doing was cramming like mad to get that game out the door."

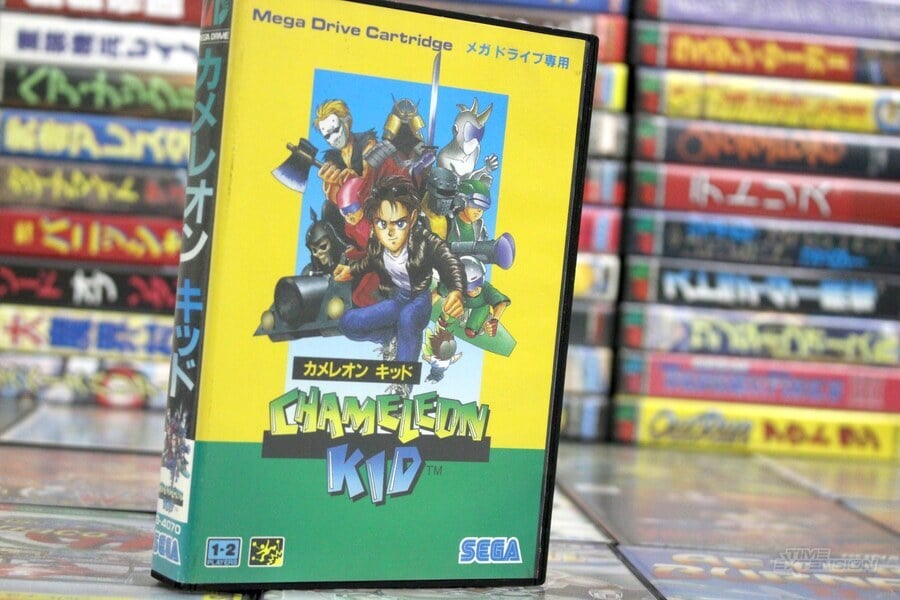

Next up was Kid Chameleon, a title which, at the time, was compared favourably to Nintendo's Mario by the gaming press. This, as it turns out, was intentional on Cerny's part. "Oh, it absolutely was inspired by the Mario games. We had our own direction we wanted to take things, but we were very conscious that the other platform had these extraordinarily high-quality platformers."

Sonic 2 would, of course, be one of STI's most famous efforts and broke sales records for the time. However, as Cerny recalls, even laying down the basic foundations for the game was tricky. "The first question was, what game should Naka and Yasuhara be making? We were told 'not another Sonic' because it was too soon. They didn’t want one for 1992. Then, two months later, they changed their minds because Sonic was driving the sales of the hardware, and people couldn’t get enough of it. That meant that when it finally came down to it, we only had about nine months to make the game. That was obviously a challenge from that perspective. We had a good number of Japanese folks from headquarters in Tokyo, and a good amount of people hired locally, and at that point, it became a bit of a culture clash. From Sonic 3 onwards, the team split, and Naka worked solely with Japanese staff. No more working with Americans."

Cerny's time with Sega would come to a close in 1992, and he joined the newly-formed Crystal Dynamics, where he would get the chance to work on the exciting new 3DO hardware platform, spearheaded by EA founder Trip Hawkins. He then joined Universal Pictures' multimedia division in 1994 before starting up his own consultancy firm in 1998 to work with the likes of Naughty Dog, Insomniac and Sony. Since 2007, he has been heavily involved with Sony's gaming hardware, working as the lead system architect on the PS4, PS Vita and PS5.

Even so, he has fond memories of his time at Sega, and he views the oft-overlooked Master System as a significant stepping stone for the company as a whole. "Without the Master System, there would be no Genesis," he says. "A lot of genuinely talented game creators cut their teeth making games on the Master System; not just Yuji Naka, but also people like Rieko Kodama, one of the first notable female artists in the industry, who worked on Phantasy Star. Without the console, these people might not have gone on to do the things they eventually did; that's quite a legacy!"