As part of our end-of-year celebrations, we're digging into the archives to pick out some of the best Time Extension content from the past year. You can check out our other republished content here. Enjoy!

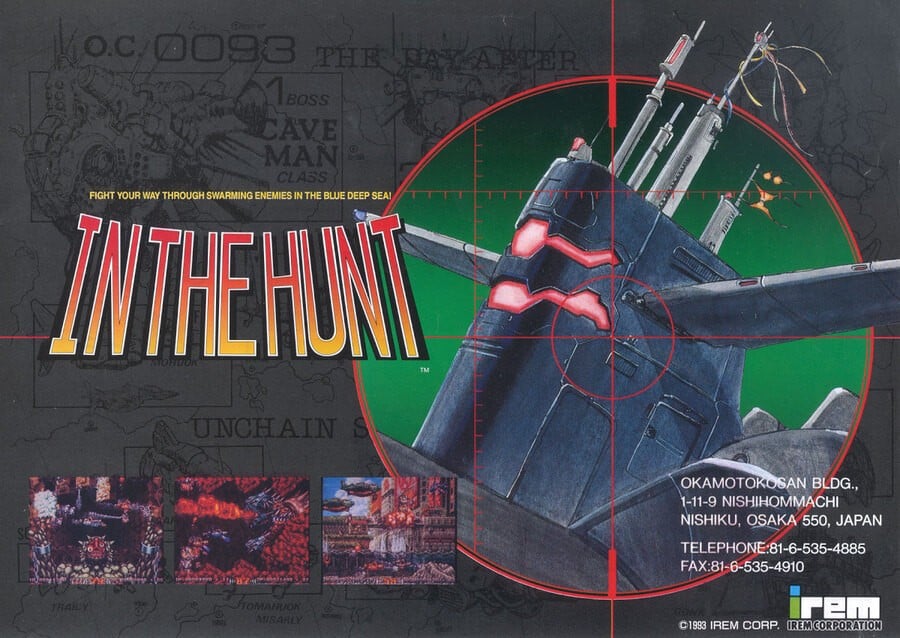

While the Metal Slug series of run-and-gun platformers has gained cult status since its origin in 1996, players might be unaware of its two direct predecessors by Irem: Geo Storm / GunHazard II from 1994, and the even earlier In The Hunt (known as Kaitei Daisensou in Japan) from 1993. Geo Storm is, sadly, both obscure as an arcade game and mysterious regarding its creation and legacy. Staff at Irem were never properly credited on anything, so unless developers admit to working on a game – or out their colleagues – we'll never know. It's a sad reflection of Japanese company politics, especially given the important legacy Irem has as the developer of the genre-defining R-Type.

In The Hunt, however, we know quite a bit about, thanks to its director Kazuma Kujo. He was involved with the R-Type series, created In The Hunt and the original Metal Slug, and later on worked on the likes of Steambot Chronicles and the Disaster Report series, and more recently was the director on R-Type Final 2. He joined us for late-night coffee and a chat at a swanky Tokyo hotel, where we took photos and spent three hours grilling him on his impressive portfolio. His signature pose is to wear shades in every photo – because when you're cool, the sun shines on you 24 hours a day.

Kazuma Kujo's career at Irem started in 1989, on R-Type II, as a tester. "The head of the business division was looking for someone who was really bad at shooting games," he explains. "He came to the department for planners and asked, 'Who is the worst at shooting games?' <laughs> They said it was me, so that's how I got involved in testing for R-Type II. I actually played it for 30 minutes, and they told me that I was too bad at it, so I was actually taken off that role. So bad... I am the worst at shooting games. <laughs>"

This is ironic, given that Kujo-san would go on to create In The Hunt, a magnificent shmup which subverts most of the genre's tropes. After R-Type II, Kujo-san was involved in Shisenshou: Match-Mania (GB, 1990), Air Duel (ARC, 1990, credited as "Tsumi-Nag"), and Superior Soldiers (ARC, 1993, "Oni-Nag"), before helming In The Hunt (ARC, 1993, credited as "Tobi-Nag"). We had to ask, why did everyone only use nicknames at Irem? Why did he keep changing his nickname, suffixing "Nag" to them?

"For several games, I am credited under my nickname," Kujo-san tells us. "At that time, the vast majority of Japanese companies did not allow you to put your real name in the credits; Japanese game companies were closed off and insular and prohibited the disclosure of staff's real names. That's why we used nicknames. Certainly for Kaitei Daisensou, because I was the director. But I'm also credited for some other games as planner. I think I was always quite angry when I was in my 20s. I was frustrated about my shortcomings as a game developer and also about things that didn't go as I wanted them to. So that's why in my 20s I had nicknames like Oni, or Kire, or Tsumi, because I was angry. Oni is an ogre, or demon. Kire means anger, or it can mean snapping. Tsumi means sin, or wrongdoings."

We pressed for details on his colleagues – for example, who were Susumu, Hamachan, and (most importantly) Meeher? The last of these played a key role in Undercover Cops, Geo Storm, and the Metal Slug series. Kujo-san was reticent; he remembers all of them, they were his friends, but if they had not come forward to reveal their own identities, he did not feel comfortable outing them.

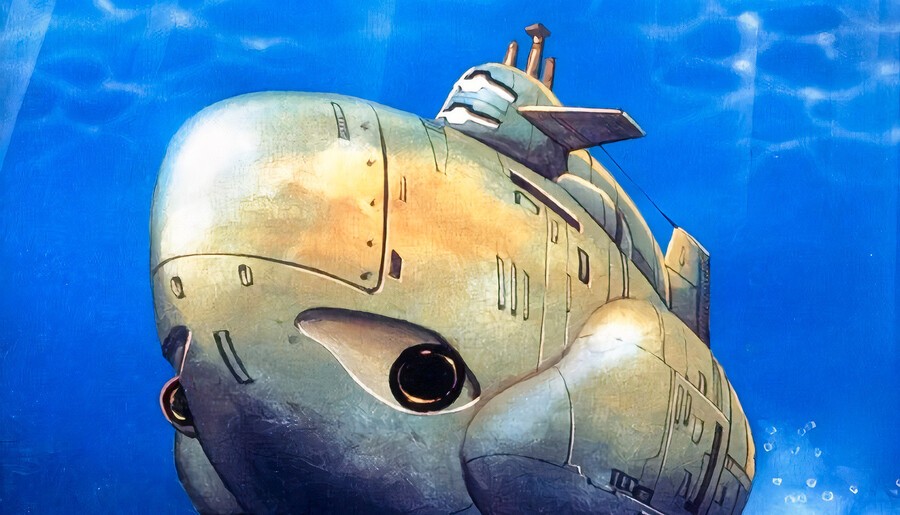

Kujo-san's revelation about being bad at shooting games is interesting because In The Hunt feels to be in defiance of the genre's then norms and, while this is speculation on our part, we wonder if his perceived lack of skill subconsciously encouraged him to deconstruct the shooting genre in interesting ways. In other words, it provided a novel way of thinking compared to more skilled or entrenched players. Not only does In The Hunt eschew the traditional outer space theme of most shooters in favour of submarines, but as a result of this it avoids many of the staples commonplace by 1993. (As an aside, if two players finish In The Hunt they need to fight to the death, which you may recognise from another popular arcade game.)

As Kujo-san reveals, In The Hunt's unique characteristics were deliberate choices. "The decision had already been made that we needed to create a shooting game; likewise it had been decided this shooting game must support two simultaneous players. The thing is, I didn't like how most shooting games were set in outer space, and I didn't like how the screen was forced to keep scrolling, even after one of the players died. It just keeps flowing and the player has nothing to do. So I was determined to make a different kind of shooting game."

Rather than look skyward for the game's setting, Kujo-san cast his glance in the opposite direction: the ocean. How he actually hit upon the idea of setting the game underwater is amusingly unorthodox. "You want to know about when I was sneaking out the office to sleep in the park?" laughs Kujo-san when quizzed on this. "At that time I needed to come up with a plan for this new game, but I couldn't come up with any ideas for weeks - maybe around two months. I would go to work, but from morning until late afternoon I would tell my boss I'm going out of the office. And I would take a walk to a nearby park everyday, and I would look at the bushes, and I would look at the middle-aged women playing tennis, and I would sleep on the benches. <laughs>"

I am here now thanks to my generous boss, though I was a bad employee for leaving the office. I think that was a very good aspect of Irem back then because they were forgiving about those things

It was during one such trip to the park that the inspiration hit him. "Laying down with my eyes closed I heard a water fountain and thought maybe it would be good to have a game underwater. After thinking that I returned to my office, and as I was walking back I saw some highways, and I thought maybe it would be cool to have a game where a submarine would be going around the city! So I told my boss about my idea, and he said to go with it. So basically the idea came when I was outside of the office and going to the park every day. I am here now thanks to my generous boss, though I was a bad employee for leaving the office. I think that was a very good aspect of Irem back then because they were forgiving about those things."

From this idea, some of In The Hunt's key gameplay innovations emerged. "Thinking about what would happen inside the water itself was really new," Kujo-san says. "I would talk with the people working on the visuals about - for example - what a missile would look like when it's launched and what would happen to the water, to the flow. I think having submarines and having the underwater setting brought a lot of originality. I felt that way throughout the entire development process."

You need to view this in the context of 1993, in a post-Gradius and R-Type world, but before danmaku or modern indie shmups like Sine Mora. There had been a lot of shooters before In The Hunt, but this was a fresh approach. The screen does not automatically scroll but is moved only by the player (or players), meaning if one dies the other can hang back and wait for their partner to get into the groove. There are also no screen-clearing power bombs and no Option modules. In addition, your vertical weapons are affected by underwater physics, giving them a delayed idiosyncratic sensation. Depth charges lazily sink backwards, having an irregular downward trajectory, while balloon mines float to the surface in an equally sedate manner. In contrast, should a player breach the water's surface it's possible to fire at aircraft using standard projectiles. Players need to deal with enemies in the air, floating on the surface, and moving beneath the water, along with sometimes navigating maze-like scenery. This constant need to change one's style of play has a mental chewing-gum effect, first one way then another, making you less inclined to zone out.

It was really hard to come up with the idea of using submarines, but after I came up with the idea, a lot of other ideas emerged... I made it so that both your weapons and also the enemy's weapons are restricted by the surface of the water

As well as enriching the gameplay, the underwater setting allowed for some truly memorable locations and set pieces. The idea of a submarine swimming through an underwater city is what led to the level Sunken Town, a gorgeous post-apocalyptic vista predating the film Waterworld by around two years. As described, you literally swim through the city, blasting a path through buildings blocking your path. In fact, this unlikely spark of inspiration set the tone for development, igniting creativity in the whole team, as Kujo-san elaborates. "It was really hard to come up with the idea of using submarines, but after I came up with the idea, a lot of other ideas emerged. I felt that way during the planning stages, and I also thought that way during the development stage. So yes, a lot of other ideas came about. I remember that when I made it, I made it so that both your weapons and also the enemy's weapons are restricted by the surface of the water."

Another favourite level of ours is the Seabed Ruins, partly for the eerie atmosphere of the civilisation seen in the background, and also for the novelty of the rock-man boss who pursues you throughout. When he eventually stops and you engage in battle, his stony face starts breaking off, revealing living flesh beneath, as autonomous eyeballs fly out to attack. It's the sort of grandiose spectacle the best arcade games were famous for, to encourage onlookers to part with coin. We start describing the boss, hoping for an anecdote, but clearly, Kujo-san is also fond of it. He cuts us off mid-sentence, laughs, and starts miming the boss' movements as if ascending an invisible ladder in the hotel's VIP lounge. It's a beautiful moment as we all laugh together.

"Oh yes!" he laughs. "In terms of that boss, who climbs up, I wanted to make that stage different from all the other stages! It's a vertical stage, even though the game is a horizontal scrolling game. We came up with the idea of an underwater temple, kind of as a joke, but everyone took that joke seriously, and we ended up incorporating it. Actually, out of the six stages, it was developed to become the 5th stage. In other words, it was one of the last stages that we developed. But everyone in development thought it was a really fun and unusual stage, so we decided to push it towards the front. So that's why it ended up being in one of the earlier stages. I think it was stage three, or something like that?"

It's a vertical stage, even though the game is a horizontal scrolling game. We came up with the idea of an underwater temple, kind of as a joke, but everyone took that joke seriously, and we ended up incorporating it

The anecdote reveals an interesting bit of trivia regarding the regional differences for In The Hunt. The Seabed Ruins is the 5th stage in the "international" version of the arcade game, as the team initially intended, whereas the Japanese version has it as the 3rd stage, as they ultimately decided. Japanese console releases on the PlayStation and Saturn copied the order of the Japanese arcade game. The change is interesting since fans have commented that the international order feels correct, compared to the Japanese order, even though the latter is what the team thought would be more enjoyable.

We'd like to think that in 20 years time, when In The Hunt is reaching its 50th birthday, historians will cite it as a high watermark of pixel artistry that's no longer made. Throughout it is resplendent with miniature details; it would not be an exaggeration to say that in some instances, In The Hunt displays even more detail than Metal Slug. Just look at the stage The Channel (international 3rd; Japanese 2nd). With enough power-ups you can send missiles to destroy the first bridge, causing fleeing civilians to run off the edge and into the water. Also when the construction vehicle hits the trucks of cattle, they plunge below and swim about. The details and animation in these exquisitely tiny sprites is incredible.

We describe the above graphical touches and enquire as to how difficult they were to create and how long it took. Immediately Kujo-san smiles, recalling the scene being described. "Yes! <mimes little people falling and splashing in water> The graphics took time and effort, it's true. But when it came to creating 2D visuals and animation, my team was able to work at breakneck speed. We needed a lot of energy, but we produced those graphics faster than you think."

Kujo-san and his team would finish In The Hunt for arcade launch in April 1993. PlayStation and Saturn ports followed in 1995, with more recent Switch and PS4 releases in 2019. Meanwhile, after In The Hunt, developer Irem would produce Geo Storm for release in 1994. Sometime after, it announced it was backing out of game development. Staff left the company en masse, leading to the formation of Nazca Corporation, of which Kujo-san was a co-founder. He then created Metal Slug as a follow-up to In The Hunt, but with an undeniably strong resemblance to Geo Storm.

All of these events, however, are best saved for a later article. Until then, whether you play the Japanese Kaitei Daisensou or localised In The Hunt, you're in for a good time.

Comments 2

I always had a soft spot for Irem. They did a lot of quirky and interesting stuff like this. This was really enjoyable to read. I love that the idea came to him by napping at the park. Game development sure has changed. I haven't played a ton of In the Hunt, and when I did, it crushed me on its default difficulty. I'll play it again for sure. Its visual style alone makes it quite memorable and takes it to a higher level, but it has a lot of good gameplay ideas too, so it's not just a matter of being visually appealing.

Kujo-san is wrong, I am the worst at shooting games. 😉 The only one I’m good at is Axelay.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...