It’s been an astonishing 50 years since the debut of the Magnavox Odyssey, the world’s first-ever game console. Having said that, we can’t celebrate its anniversary with any degree of accuracy - the exact launch date of the machine is unknown, and all we can say for certain is that it went on sale in the United States at some point in either August or September 1972, making its way over to the UK the following year. But whenever it arrived in people’s homes, it caused a sensation.

Up until that point, television had been an entirely passive medium. But the Odyssey suddenly allowed TV viewers to become players, controlling objects on the screen in what must have been a revelatory experience. Anecdotal reports from early adopters rave about the machine, calling it things like "the most unique product I’ve seen" and "the best product on the market." There were even stories about Los Angeles Air Traffic Control using an Odyssey to train recruits by simulating air traffic and about the University of Kentucky measuring the brain waves of monkeys while the simians moved objects around on the screen. In short, it was enormously exciting: no one had seen anything like the Odyssey before.

Although perhaps we should qualify that statement. The Odyssey was by no means the first time a game was put onto a screen: as far back as 1952, the University of Cambridge computer scientist Alexander Shafto Douglas had created a game of Tic Tac Toe on a room-filling EDSAC computer, and the American physicist William Higinbotham made the game Tennis for Two in 1958 using an oscilloscope. More importantly, Steve Russell and others at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology coded the game Spacewar! in 1962 on a PDP-1 computer, and code for the game was circulated to computers at other institutions. Spacewar! formed the basis for Computer Space, the world’s first arcade video game, which was created by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney in 1971 – the pair would go on to found Atari the following year.

And it’s Atari that tends to dominate any conversation about the early history of video games, perhaps unfairly overshadowing the achievements of the Odyssey and its creator, Ralph Baer – after all, the Odyssey predates the release of Atari’s first arcade game, Pong, by several months, and there’s convincing evidence that the Odyssey directly inspired Atari’s smash-hit machine, as we’ll see later.

Where It All Began

"What started as an idea to build a "box" that could make novel use of any garden-variety TV set became an industry... and a whole new way of playing games that radically changed how large subsets of this planet's population spend their free time" - Ralph Baer, Videogames: In The Beginning

Much of what we know about the early history of the Odyssey comes courtesy of Ralph Baer’s fascinating autobiography, Videogames: In The Beginning, which was released in 2005, nine years before his death at the age of 92. After serving in military intelligence in the Second World War, Baer graduated with a degree in television engineering from the American Television Institute of Technology in 1948, and soon after he started working at Loral Electronics in the Bronx, where he helped to design a new television set. In his book, he says he began wondering about the possibility of building some kind of game into the new television in around 1950. "Some of the test equipment I used during this development job allowed me to create lines and checkerboard patterns on the screen," he said. "I thought that it wouldn't take much to make similar circuitry into a game."

But his superior dismissed Baer’s proposal to add a game to the TV, saying that development was already behind schedule – and it would be many years before Baer revisited the idea. In the late 1950s, he moved to the defence-electronics firm Sanders Associates in New Hampshire, where he concentrated on developing electronics for things like airborne radar countermeasures and antisubmarine warfare. But in 1966, while on a business trip to New York, the idea of making a game for a TV set entered his mind again. He jotted a few notes on how it might work, laying down the foundations for what would eventually become the world’s first game console. We even know the exact date this happened – 1st September 1966 – since Baer kept meticulous notes throughout the development process, a paperwork trail that would prove pivotal in the later lawsuits about who invented what, and when, in the newly emerging world of video gaming.

Baer assigned technician Bob Tremblay to construct a proof-of-concept prototype based on the ideas he had jotted down. Called the 'TV Game Unit #1', it was constructed using vacuum tubes and successfully showed that they could put a line on a TV screen and move it around. Of course, the project had nothing to do with defence electronics, but as chief engineer in a huge department, Baer had the budget and leeway to experiment.

Baer showed the TV Game prototype to the company’s head of research and development in December 1966 and was given the green light to keep developing the concept, along with a small budget for the project. Sanders engineer Bill Harrison was brought in to help develop some games, and later he was joined by Bill Rusch – although progress had to be halted periodically as the engineers were diverted away to work on high-priority defence-related projects.

Not A Chip In Sight

The main difference between Baer’s machine and later, programmable consoles like the Atari VCS was that all of the functionality was hardwired. There were no microchips in sight, since these were deemed too expensive at the time for a commercial product – instead, the guts of the machine were made up of a tangle of wires, diodes and capacitors that each performed a different task. There were ‘spot generator’ circuits to make movable white blobs that could be stretched into vertical or horizontal rectangles, as well as various other circuits controlling things like collision detection. Interestingly, early prototypes included functions like colour TV output, timers and random number generators, but these were discarded as development progressed, being deemed too costly; Baer initially wanted to make a device that could retail for $25, although he later revised that to a more practical $50.

Baer, Harrison and Rusch came up with a wide range of ideas for games, only some of which made it through to the finished product. One discarded idea involved using a light pen to make a quiz game, where players would have to register their answers by pointing the pen at white spots on the screen – the machine would be able to tell the right answer from the wrong ones by detecting whether the number of times the spots flashed was odd or even. Another discarded idea was a ‘pumping game’, where one player attempted to fill a bucket while the other tried to empty it, all represented by a line being pushed up or down and a screen overlay. It involved rapidly hammering a button, an early precursor, perhaps, to button-mashing games like Track and Field.

The basic controller design was nailed down fairly early on, with two dials controlling vertical and horizontal movement, respectively – but the group also developed a sort-of joystick with a golf ball on top for use in a golf-putting game. That didn’t survive beyond the prototype stage, but the light gun they came up with – actually more of a light rifle – did, and worked by picking up bright patches on the screen using a photo sensor. (That also meant you could cheat by, for example, pointing it at a lamp.) The engineers created a game where one player moved a target around on the screen while a second player attempted to shoot it; in a similar fashion, there were several ‘cat and mouse’-type games where one player would manoeuvre their on-screen blob to try to catch the opponent’s blob. Most importantly of all, in late 1967 Baer et al. came up with a series of sports games based on Ping-Pong, Tennis, Hockey and others, all of which involved manipulating rectangular bats to hit a moving ball.

Who’s Going To Pay For This Thing?

By January 1968 the team had reached version number seven of their TV Game prototype – a version they nicknamed the ‘Brown Box’ owing to the wood-effect vinyl stickers it was covered with. They were confident that they had come up with something that people would be interested in buying – now they had to find someone to sell it. Sanders Associates was primarily a defence firm, so there was no way the company could market the game system by itself. It needed to sell the license to a partner.

Baer initially pursued a deal with the cable TV firm TelePrompTer, which had developed the eponymous display device (also known as an autocue) in the early 1950s, and which at the time was well on the way to becoming one of the largest cable television providers in the United States. Baer reasoned that his tennis game with its blank background looked a bit sparse on its own, but it would be possible for a cable TV company to film a real tennis court from overhead, then the moving bats and ball could be overlaid on top of the TV picture. He envisioned that the cable TV company could provide the games system as a way to set its offering apart from that of the competition.

Talks progressed quite far with TelePrompTer, but eventually broke down in late 1968. So in January 1969, Baer and his colleagues began targeting US TV set manufacturers instead, giving demonstrations of the Brown Box to companies including RCA, Zenith, Sylvania, GE, Motorola and Magnavox. RCA was interested for a while before eventually backing out, and ultimately it was Magnavox who saw potential in Baer’s baby. But contract negotiations dragged on for months, and it wasn’t until January 1971 that an agreement was signed between Magnavox and Sanders.

Once the ink was dry, Magnavox took over development of the Brown Box, with Baer relegated to a purely advisory role. The TV firm called the new device the ‘Skill-O-Vision’ although the name was changed to Odyssey in early 1972 after the Skill-O-Vision moniker received a lukewarm response from focus groups. Most importantly, Magnavox came up with the Odyssey’s wonderfully retro-futuristic white and black casing, with just a hint of woodgrain around the edge. It remains one of the most distinctive-looking consoles ever made.

The biggest alteration made by Magnavox was introducing cartridges for the Odyssey. On Baer’s Brown Box, users could select different games by flicking switches on the front, whereas on the Odyssey, changing games required slotting in different cartridges. But the games weren’t actually stored on the cartridges per se – instead, the carts ‘wire-jumped’ the circuits into a different configuration, causing the spot generators to make rectangles appear in different ways on the screen. The first ‘true’ cartridges, each containing code for a complete game, wouldn’t appear until 1976, with the debut of the Fairchild Channel F.

When it came to marketing the Odyssey, Magnavox faced a challenge since the concept of video games and game consoles barely existed at the time. The term ‘video game’ only began to be used widely in 1973, and even then this term was usually applied to arcade machines – home consoles were often referred to as ‘TV games’ for much of the 1970s. In the early advertising for the Odyssey, it was referred to as an ‘electronic game simulator.’

Baer suggests in his book that commercials for the Odyssey made it seem like the console could only be used on Magnavox TVs, thus hurting sales, but an investigation by Kate Willaert for the Video Game History Foundation found little evidence to back this up. Almost all of the adverts for the Odyssey specifically say it can work on any TV.

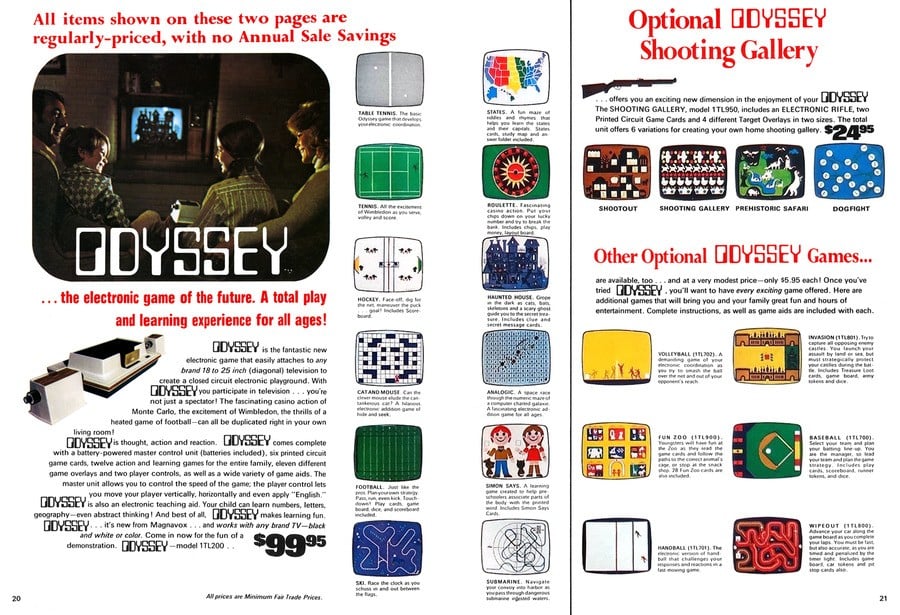

However, something that almost certainly did restrict sales was the fact that the Odyssey was only sold at Magnavox dealerships, thus drastically limiting the potential market. There was also the question of price: the Odyssey initially retailed for $99.95 (equivalent to around $700 today), and the light gun was sold as an optional extra for $24.95. This was a premium price, and far more than the $50 RRP originally envisaged by Baer. Even so, the Odyssey went on to sell an impressive 350,000 or so units by the time production ceased in 1975, helped by discounting as time went on.

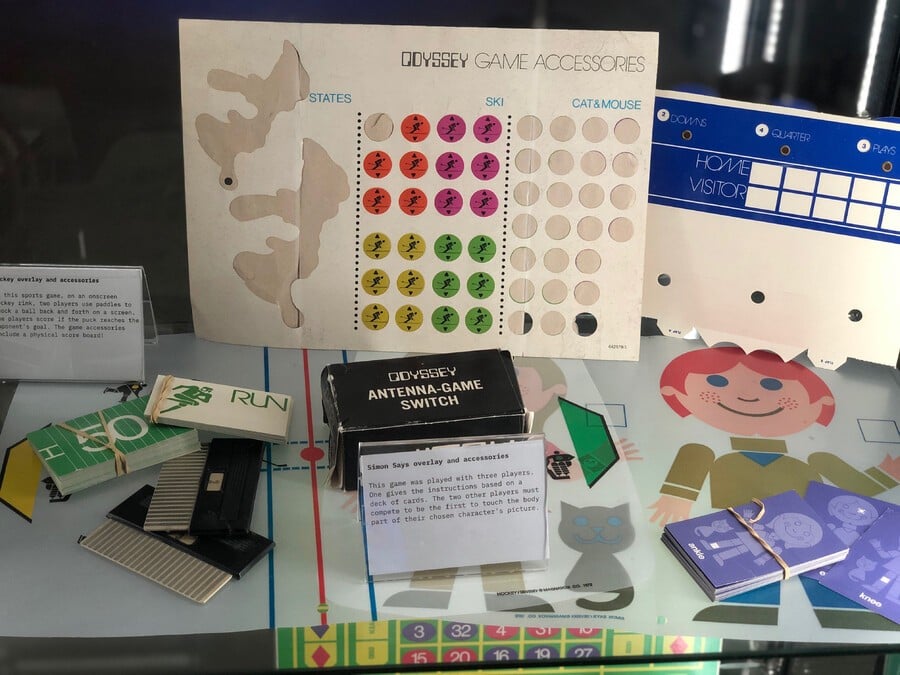

The Odyssey came with 12 games, with an additional six being sold separately, joined by another four in 1973. The light gun also came with four titles, and almost all of the games used a thin plastic screen overlay to add colour and graphics. But one of the original 12 games in particular caused a storm.

Pong Shenanigans

“When the Magnavox Odyssey is brought up, it's usually in tandem with Atari and Pong and the lawsuit,” says Michael Pennington, a curator at the National Videogame Museum in Sheffield. He’s referring to Magnavox successfully pursuing Atari and others over Pong and the many copycat variants of it, which all bore a remarkable similarity to the Table Tennis (aka Ping-Pong) game on the Odyssey. They weren’t exactly alike: the Odyssey game allows you to move the vertical bat both backwards and forwards as well as up and down, and there’s a separate switch to control ‘English’, i.e. putting spin on the ball. Pong, meanwhile, used a segmented bat, where hitting the ball towards the edge of the paddle sent it spinning off at a different angle than if you hit the ball with the centre. Pong also featured a score counter, which was lacking in the Odyssey title. But otherwise, the similarity is remarkable.

Magnavox began showing off the Odyssey to the public in May 1972 as part of a touring show of its upcoming wares, the so-called Magnavox Profit Caravan. The show stopped at the Airport Marina Hotel in Burlingame, California, and Nolan Bushnell’s signature is clearly visible in the guest book, dated 24th May. The first prototype for Pong would emerge a few months later, designed by Al Alcorn according to instructions given by Bushnell.

Pong was a runaway success, spawning myriad copycats, like Sega’s Pong Tron from 1973, as well as a whole fleet of home consoles, most famously Atari’s Home Pong from 1975. Manufacturers rushed to cash in on the craze, and hundreds of different Pong consoles were released in the late 1970s (for an overview of them all, see David Winter’s excellent PONG-Story website). Naturally, Magnavox took exception to this, and successfully sued many of the manufacturers, reportedly reaping around $100 million from lawsuits relating to the various patents for the Odyssey. Atari made an out-of-court settlement with Magnavox in 1976, just before the sale of the company to Warner Communications.

Magnavox (and Sanders Associates) may well have made a tidy sum from these lawsuits, but the Odyssey and Ralph Baer are far less well remembered by the general public than Atari. “There's a canonisation of video game history in a sense, particularly from an industry perspective,” says Pennington. “[It] starts with Atari, and ends – currently – with Xbox and PlayStation. And those other systems that aren't inside the canon … get put by the wayside.”

Not at the National Videogame Museum, though, where the Odyssey takes pride of place. “It's been a permanent fixture on the gallery floor in the museum,” says Pennington. “And of all the things we've changed and switched around since we've been in Sheffield, that stayed constant, like a good old North Star.” Even so, it baffles many visitors. “I think a lot of people come to the museum and have no idea what this thing is,” Pennington continues. “Especially younger kids, because it's so lost in time, and gaming conversations in a modern setting would never fixate on this type of thing.”

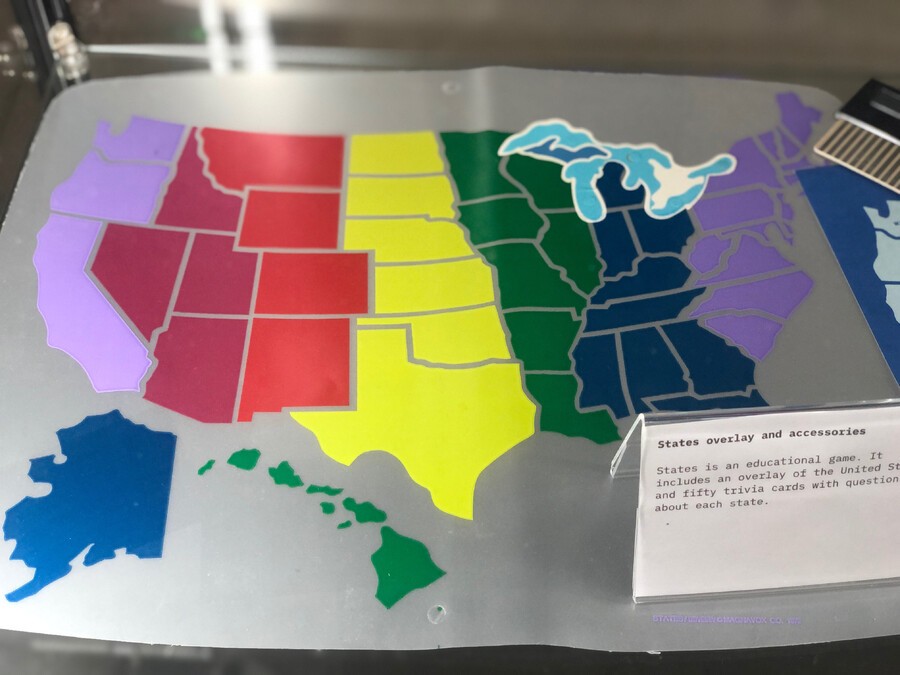

Still, there’s also something fascinating about the otherness of the machine, with its delicate screen overlays. “You have the same setup for most games, where you're moving a square around a blank screen, essentially, and so the genius of it is all these screen overlays and attachments, which … stick to the static of an old-style TV,” says Pennington. “So you've got games like States, [where] the dot lines up with one of the American states on the map, and then you have to guess it.” Other games, such as Roulette, use paper money, and there are games like Simons Says that use cards or dice. It’s a fascinating, unique machine that bridges the gap between traditional board games and what we would now call video games.

It's also incredibly delicate, and far too fragile to be played by the public – although the museum does switch it on occasionally to check it’s still in working order. The thin plastic screen overlays and many paper components are also something of a curator’s nightmare. But Pennington loves it. “It's one of my favourite objects in the collection, just because of what it represents. The history behind it, the woodgrain, the fact that it was marketed specifically as the first home console: such a massive shift away from what had been the previous focus of arcade cabinets and machines. I think it's a really wonderful piece of technology."

Comments 1

I remember seeing this in the shop windows in the late 70's when I was a kid and wanting one.

It looked so futuristic back then and I had never seen anything like it.

Great story and it brings back some good memories, thanks.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...