Back in August 2012, Sony closed the doors of Studio Liverpool. Formerly known as Psygnosis, the studio was arguably most famous for its Wipeout series of futuristic racing titles, but it's easy to forget that it enjoyed a rich and vibrant history long before it was acquired by Sony to spearhead its first PlayStation console.

Founded in 1984 by Jonathan Ellis, Ian Hetherington, and David Lawson, Psygnosis would become an iconic brand within the 8 and 16-bit home computer markets, publishing cult titles such as Shadow of the Beast, The Killing Game Show, and Barbarian. With its famous "owl" logo — designed by none other than Roger Dean, the man behind the current Tetris logo and countless rock album covers for bands like Yes and Asia — and a penchant for graphically arresting titles, the company quickly earned the reputation of being forward-thinking and willing to embrace new technology.

This would be cemented by the firm's first tentative steps into the realm of CD-ROM with FMV-based shooters Microcosm and Novastorm, the latter of which would launch on the PlayStation after Sony had made Psygnosis a wholly-owned subsidiary in 1993. Psygnosis would support Sony's new 32-bit PlayStation console with a raft of releases, including Krazy Ivan, G-Police, Colony Wars, Destruction Derby, Assault Rigs, and Formula One — although some of these games were developed externally by the likes of Reflections and Bizarre Creations, they remained unmistakably faithful to the publisher's core ethos.

Buy why try to recount the illustrious history of this sadly defunct British institution with hazy recollections when you can give a platform to someone who was actually there at the time? Richard Browne is EVP of Gaming and Interactive Media at Evergreen Studios in LA and has worked at Eidos, Domark, Microprose, and THQ, but he cut his teeth during his time at Psygnosis in the early '90s. Serving as Chief Designer of the Advanced Technology Group, Browne was responsible for pushing CD-ROM development within the studio and — along with his team — laid the ground work for the company's early work on the PlayStation console. Take it away, Rich.

I first met Jonathan Ellis at the PCW Show at Olympia in 1989. At the time I was working for Domark, manning our booth walking around in a Hard Drivin’ jumpsuit. As I wandered over to the Psygnosis booth on a break, cheque book in hand (this was back in the day that “trade shows” actually included consumers — people sold things and at the time Shadow of the Beast had just been launched and I went to buy a copy) it so happened that Jonathan was manning the sales booth. “Do you really work for Domark?” he asked, which perplexed me a little given that I really can’t think of why anyone would voluntarily wander around in a Hard Drivin’ jumpsuit. “Yes, I do,” I replied and he passed me a copy of Beast and waved away my cheque. He asked me what I did, I told him, and he let me know that Ian Hetherington was looking for some good Project Managers, and that I should go over to their meeting room and say hello.

I was somewhat in awe of what Psygnosis did and stood for even before I walked into that room. While many of the games they produced were renowned somewhat for style over substance, they just oozed quality and the presentation was just pure class. The Roger Dean logo, the black box with sleeve cover, and then with Beast the “free” t-shirt that in actuality cost £10; everything about the product from the moment you picked it up felt worthy of your hard money. In that room, though, lay the future. As I entered and met Ian, across the table sat a grey box with a CD drive in the front. On the screen some exquisite 3D rendered graphics was seamlessly playing. Psygnosis were known for their intro sequences and with the advent of Sculpt 3D they had become even more elaborate, but compressing and running them from an 880k Amiga disc into limited RAM was challenging and slow. Here, on an FM-Towns system, those intros and the first demo of Planetside was in constant rotation without a hitch. I was flabbergasted. It took me over a year to get there, but Ian offered me a job and to Liverpool I duly moved.

Back in those days Psygnosis was located on the South Harrington Docks just south of the Albert Dock, famously home of the Beatles museum and UK TV show This Morning with Richard and Judy. There were long warehouses with office space above and in here the mighty Psygnosis had four offices. Psygnosis used one of the warehouses as a distribution site, run by Roy Barker — a most wonderful man who also happened to be author Clive’s brother. The main office was split into two rooms, on one side “publishing” where marketing, sales, PR and Jonathan sat, and on the other side of the wall was the development team. The one thing that startled me coming from Domark — where marketing was everything — was how much development ran the direction of the company. It was always investment in product over anything else and the core team reflected that. Most of the code development was done externally, but internally this was supported by art and tech staff that would ensure that the gloss and polish was up to Psygnosis' scratch. Jim Bowers, Neil Thompson, Garvin Corbett, and Jeff Bramfitt made up the core art team, with Lee Carus and Mike Waterworth the other key members, and each contributed to various projects in development internal and external. They were by far the most astounding art team I’d ever met. These geniuses were frequently tasked and teamed up with the external groups that Psygnosis worked with in order to ensure the same standards could be applied across the board to all their games.

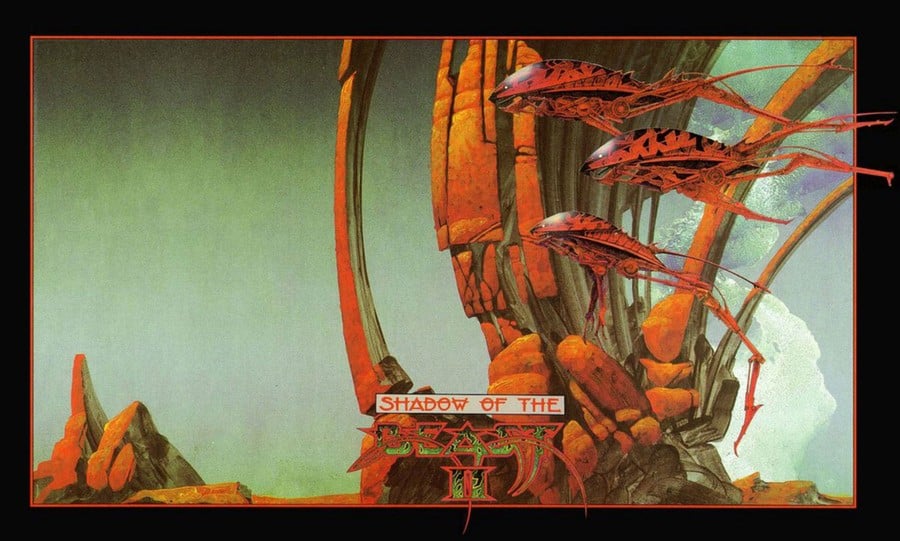

What was so very different about Psygnosis was this symbiotic relationship it had with all its developers. They’d set a bar, a reputation, and as a result there were a lot of one or two man teams out in the country that wanted to work with Psygnosis. They were chosen purely on ability, and they were some amazing individuals. Martyn Chudley wrote most of The Killing Game Show from Devon with his art being produced in house in Liverpool. Given the constraints of the era's modems it behoved him to move North and he did. He stayed completely independent while working under Psygnosis’ roof, partnered for Wiz’n’Liz with Mike Waterworth. Martyn, as many will know, evolved from being Raising Hell and became Bizarre Creations, with every ounce of Psygnosis support. Bizarre went onto produce the most exceptional F1 games, Fur Fighters and the Project Gotham series for Microsoft. The Shadow of the Beast team, Reflections — composed of Martin Edmonson and Paul Howarth — went onto create several big titles for Psygnosis, such as the Beast trilogy and Awesome, as well as moving into consoles with Destruction Derby and Driver for the PlayStation before becoming part of Ubisoft. Travellers Tales — Jon Burton and Andy Ingram — found a home at Psygnosis with the incredible Leander and went on to produce Puggsy and Mickey Mania, among others. Apparently they’re still quite successful today, as Jon can verify! Psygnosis was a hive of brilliance and with Ian Hetherington leading it, it pioneered where gaming has gone today.

Primarily Ian understood that technology was driving things, and on the tech side he was ramping up CD-ROM development in-house with a crack team of programming staff, led by David Worrall (who had written Carthage) along with Paul Frewin and veterans (yes, even in those days) from Denton Designs and Imagine: John Gibson and Graham “Kenny” Everett. These guys had been immersing themselves in video codec research and CD data layout structure which allowed the streaming FMV to work so well on the FM-Towns. This group became known as the Advanced Technology Group was purely an R&D team for some time; without producing product the company had to fund such ventures by continuing to be successful on the publishing side — it would help to have a cash cow.

From the minute DMA and Psygnosis worked together on Menace there was a foundation of collaboration. There was a massive amount of mutual respect; in Psygnosis, DMA knew they’d found a true partner and in DMA Ian knew they’d found some real brilliance. When the DMA team brought Lemmings to Psygnosis there was not only a fundamental belief in the product but a complete understanding that it had to be handled right or suffer the consequences. Lemmings was a brilliantly engineered product from conception to release. I remember being in Milpitas with the Atari team when the Amiga demo appeared packed in with CTW. It was genius, everybody at Atari was astounded by it, and yet it didn't appear that Christmas — it was held off until February. It seemed insanity, but the product wasn't ready and the game wasn't released until it was perfect. Frankly it was, too. Lemmings — even today — stands the test of time; it was a piece of genius. The DMA / Psygnosis partnership is one that would grow and flourish, with DMA producing a stream of great products – Oh No More Lemmings, Walker, Hired Guns, and Lemmings 2, as well as partnering with Psygnosis on numerous technology projects.

Pushing limits and technology really was much of what Psygnosis was about, focusing on the Amiga solely when the ST had a bigger installed base and subsequently their investment in CD-ROM technology long before anybody in the mainstream had given it a single thought. It positioned Psygnosis in a very enviable place, and not long after I arrived there in early 1991 we started doing some prototype work on what could have become our very first production CD title, a joint venture with a US-based company with the biggest license known to man. We spent many months working on the pitch — myself and David Worrall handling the design work — and the now-formed Advanced Technology Group working on how to make FMV interactive. The FMV was initially started off on the Amiga with Sculpt, but before too long Psygnosis made its first investment in Silicon Graphics hardware and SoftImage. This was unheard of in the games industry. People were slowly becoming aware to 3D on PC’s, but with the focus still firmly on home computers and 16-bit consoles like the SNES and Megadrive/Genesis, nobody was delving deep into 3D like this. When the Indigos arrived there was a hushed awe; then David Worrall set them up on the network and 3D tanks became the de-facto lunchtime thrill for everyone. Somewhere in-between, Jim and Neil rendered some really, really cool stuff for the pitch. At CES in January 1992 Jonathan and Ian took this hard work and investment to the States to wow our new partners and sign the deal of a life time, only for it to be called off at the last minute. We were devastated.

Fujitsu and Psygnosis had been talking for some time, with the FM-Towns being the only standardized CD platform out there it made for the most stable development base. In Japan the machine was fairly popular — though totally unknown elsewhere — and Fujitsu had been eyeing the console space so entrenched by SEGA and Nintendo. With that in mind they started development on a dedicated CD-based console and Psygnosis began work on Microcosm, which largely unbeknown to the Western World would become the first FMV CD-based “interactive movie” to be released (in the West with the PC CD market beginning to develop rapidly, The 7th Guest caught most people’s attention). It also happened to be the cover story for the first issue of UK magazine EDGE, which recently celebrated its twentieth anniversary.

Psygnosis continued to push technology forward across any and every CD format that headed toward the game market. With DMA Design they started work on the infamous and never-to-be-released SNES PlayStation, using monolithic cartridges to simulate CD drives. Microcosm was ported to Mega CD, PC CD-ROM (by Tim Ansell and the Creative Assembly – now owned by SEGA), Commodore CD32, and 3DO. Each version used custom written software compression while others were using off the shelf codecs, like Cinepak. Trip Hawkins was astounded by the quality of the 3DO video when I demoed it to him at CES in 1993. After the completion of Microcosm, Fujitsu and Psygnosis continued to work together. Having been ardent fans of the original Planetside demo they wanted a new title that truly showed off the FMV advantage of CD over cartridge — a game that would boast lavish landscapes with similar overlaid shooter mechanics. Over the course of four weeks we rendered up a design document and demo for Scavenger 4 and development started again. This time the core rendering work would be shifted across to Alias / Wavefront who had been vying to get in the doors at Psygnosis ever since we’d started using SGi’s, the game would become known on other platforms later as Novastorm.

Psygnosis continued to grow during this period, with a stable publishing slate the company went from strength to strength and opened up new development studios around the country. Psygnosis Chester was the first satellite office to open and went on to develop Sentient, followed by Psygnosis Stroud which was formed from the remnants of Microprose and developed the fantastic G-Police, and Psygnosis London who initially focused on porting Microcosm to CD32.

Aside from game development Psygnosis also moved into development kit manufacture and distribution through a somewhat chance meeting arranged with Martin Day and Andy Beveridge from The Assembly Line. Both had driven the development of the ubiquitous 16-bit development system SNASM with Cross Products before leaving to focus on code development, becoming best known for the programming work on Xenon 2. It was because of that — and their third partner Adrian Stephens' work on Stunt Island for Disney — we’d wanted to chat with them, but it quickly came back to their love of development systems and how they were eager to keep pushing them forward. Thus Psy-Q was born, a development system for 16-bit computers and consoles that would later become a key component in the history of the company.

One of the other benefits of the technological push was a lot of suitors became interested in acquiring Psygnosis for technology reasons. There were several dates with several suitors before and during that time Psygnosis began actively working with Sony Imagesoft in Los Angeles. The first project we collaborated on was Mickey Mania with Travellers Tales and Disney, along with movie licenses that the fledging publisher was working on – Last Action Hero (yes, the game that Arnie insisted he could not be shown touting a gun), Dracula, Frankenstein, and No Escape (the latter would never see the light of day). The courtship was relatively short; Sony’s entry into publishing in the US was to be a building block for a distribution network that the PlayStation would subsequently travel and they were after a similar setup in Europe. Phil Harrison had been brought on-board as the first Sony Computer Entertainment Europe employee, and along with senior Sony staff and Sony US President of Interactive Olaf Olaffsen due diligence was carried out on the company and in 1993 it was acquired. Psygnosis became SonysPigs.

I don’t mean that in any way disparagingly — it was a startling coincidence that drew more than the odd laugh. Sony hadn't bought Psygnosis to swallow them up and enforce corporate culture on them, they’d bought them for development talent and for publishing wherewithal. Jonathan and Ian went down to the big smoke to set up SCEE in Golden Square, Soho, where it would begin rapidly snapping up console titles to launch in Europe and to get the distribution network flourishing. Meanwhile up in Liverpool a photocopier had arrived in the ATG, with instructions in Japanese and much scratching of heads of how exactly we were supposed to communicate with this box that Sony Japan had sent labelled “PS-X”. Eventually we found out the only way to do this was via a Sony NEWS Workstation, which was fantastic, other than we had no way of getting hold of them. Somehow somebody managed to locate two such machines hidden away in the back storage room of a Sony store down in Basingstoke; they were duly ordered, sent up and the PS-X adventures truly began.

Fortunately, somewhere during the FMV years we realized that we were never going to achieve the level of interactivity we wanted to by playing video in the background. Even though by the end of Microcosm and in the development of Scavenger 4 we learned to do some really clever things, it became clear with the advent of games like Doom that full 3D was the way to go and we started exploring that space more and more both internally and externally. Andrew Spencer’s wonderful Ecstatica that eschewed polygons for ellipsoids was once such external venture; internally some of the ATG team started playing with full polygonal texture mapped worlds, including one project that had robots running around a boxy cityscape that would eventually become Krazy Ivan. All of this became vital as the team uncovered the power of that PS-X kit and what it was capable of; it was clear the machine was incredibly powerful but accessing that power was going to be difficult — there were some definite hurdles to clear.

The first of these was obviously if the PS-X was going to become the focus of the games industry it could not have a development system based around a machine that no one could get hold of. Fortunately Psygnosis had a solution to that and Martin and Andy came up and began the development work on Psy-Q for the PS-X. In January 1994 at CES in Las Vegas it was presented to Ken Kutaragi in hushed silence in a suite at the Alexis Park Hotel. His blessing was quickly forthcoming and the PS-X — soon to become the PlayStation — had a development system that nearly every developer on the planet was familiar with, if the actual machine they were developing for was a little more foreign.

Sony and Psygnosis put on the first developer's conference for the PSX late in 1993. SCEE had recently moved from Golden Square to Great Marlborough Street, so recently in fact the tiles floor had to be laid quickly the day of the conference. Phil Harrison, David Worrall, John White, and Dominic Mallinson presented the machine to an audience sat in quiet awe. There had been some leaked shots of the infamous dinosaur head, but the conference was the first time the full dinosaur was shown, fully animated, textured, and lit. The crowd was astounded, and this wasn't an easy crowd to impress – it truly was the who’s who of European development at the time.

Back in Liverpool work had begun in earnest on a slate of launch titles that would truly define the PlayStation in its early days. Nick Burcombe and Jim Bowers fired up the concept for Wipeout, Krazy Ivan developed from the earlier PC IDEAL city demo, Scavenger 4 was ported across to become Novastorm, Colony Wars and the Reflections team started work on Destruction Derby. There’s no question a great deal of the early success of the PlayStation, especially in Europe, lay squarely at the feet of those games, and Wipeout continued to be one of the pillars of the PlayStation for well over a decade. With the sad closure of Studio Liverpool in 2012, that may have come to an end, but signing off with Wipeout 2048 on PlayStation Vita was a fitting end to a long adventure.

Ian Hetherington and Jonathan Ellis continued to grow SCEE for a few years after the launch of the PlayStation but both eventually bowed out to enjoy their success and start new ventures. Many of the staff of those early days have remained connected to Sony in one way or another, and most of the teams we worked with in the early days went on to astounding success across the globe. It was a bunch of true pioneers pushing the boundaries and ignoring the Status Quo — their mark will forever be indelibly inked on the industry.

This article was originally published by pushsquare.com on Mon 20th January, 2014.

Comments 8

Really fascinating insight into a legendary studio - I thoroughly enjoyed reading this.

I can't think of Psygnosis without thinking Discworld. I loved those games so much when I was younger, as hard as they were. I'm not sure how involved Psygnosis were with the actual making of them - perhaps with the art? - but that owl logo, followed by that awful drone as the splash screens run through are a huge memory for me.

Fantastic article!

Psygnosis & Bitmap Brothers were my favourite devs back in the Amiga days. So many fond memories of games like Nitro, Awesome, Shadow of the Beast etc.

They were the days you'd get a massive cardboard box for the game, a 300 page instruction manual, t-shirts and loads of other goodies, These days you're lucky to get a disc!

Lol there logo useto scere me when i was little - that T Rex tech demo is impreciv and i like that music.

Great read. Great studio.

Great article, thank you guys for that! Brings back lots of fond memories...most of the games mentioned I remember playing myself, back in the days.

Great article! Psygnosis always made such amazing and slick games!

Amazing article on easily one of the best software houses ever. Will never forget playing Barbarian, obliterator, Shadow of the beast for the Amiga 500 truly ground breaking stuff. And games like Microcosm and Novastorm should be remastered or given true sequels. Imagine PS5 tech being exploited to it full potential running some awesome rail shooters.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...