Don't worry – you're not suffering from déjà vu. If you feel like you've read this before, it's because we're republishing some of our favourite features from the past year as part of our Best of 2024 celebrations. If this is new to you, then enjoy reading it for the first time! This piece was originally published on August 2nd, 2024.

It's almost impossible to talk about Metal Gear Solid 3 today without somehow mentioning the game's iconic theme: "Snake Eater".

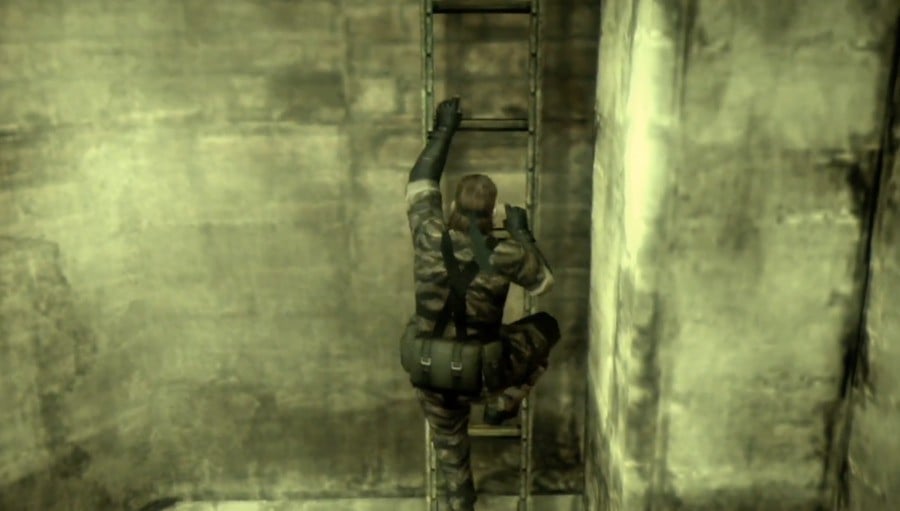

The James Bond-esque track features music and lyrics by the Japanese composer Norihiko Hibino as well as vocals from the American funk and soul singer Cynthia Harrell and has become something of a fan favourite over the years. It notably appears over the opening credits of the game, as images of Cold War headlines and the jungle setting flash across the screen, and also turns up later on, during a now-famous scene, in which the player is treated to a slightly altered arrangement while the game's protagonist Naked Snake (the future Big Boss) slowly ascends a long ladder to the top of the Krasnogorje mountains.

Last year, Konami announced that it was in the process of remaking Metal Gear Solid 3 (under the name Metal Gear Solid Delta: Snake Eater) for modern machines, so we thought what better time is there to revisit the game's classic opening track and look into the history of how it came to be. So recently we reached out to people involved in bringing the song to life, to uncover more about its history and how it touched the careers of those who worked on it — starting with its main composer Norihiko Hibino.

What A Thrill

Hibino’s career in games started back in 1999 when he returned to Japan after having spent a year studying Music Production and Composition at Berklee College of Music in Boston. Despite having no prior knowledge of video games, he quickly found himself working for Konami Computer Entertainment Japan on the Metal Gear series, landing himself the job based on a tip from a friend and due to his experience with both computer production and acoustic composition.

He received his first credit for the score to Metal Gear Solid (2000) — a Game Boy Color game that confusingly isn’t a remake of the 1998 game, but an alternate continuation of the series – and eventually graduated to become part of the music team on the 2001's hotly anticipated Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty. This was a remarkable development when you consider that just a few years prior he hadn’t even heard of the series.

"I didn’t even know of Metal Gear Solid when I got hired,” Hibino admits. “The first thing I was told by the chief was we’ve already talked with Harry Gregson Williams, the composer of famous films, and you…[will] be collaborating with him. I was like ‘What should I do?’”

Hibino is credited for six tracks on the Metal Gear Solid 2 official soundtrack CD, but his contribution was far greater than that. He composed a lot of the in-game music, but poor crediting on the soundtrack (which favoured Gregson Williams' contributions) ultimately led to a lack of international exposure. This would all change with the next entry in the series, a game that would cement his reputation as a composer.

I didn’t even know of Metal Gear Solid when I got hired. The first thing I was told by the chief was we’ve already talked with Harry Gregson Williams, the composer of famous films, and you…[will] be collaborating with him. I was like ‘What should I do?

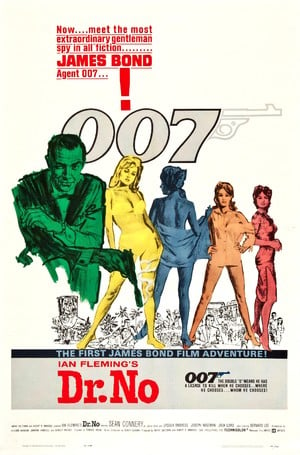

According to Hibino, the idea for Snake Eater originally came about as the game's director Hideo Kojima wanted a "James Bond-ish" style main theme to feature on the soundtrack. As he claims, he wasn't originally in the running to work on the main theme, with other musicians, including the composer and producer Rika Muranaka, submitting tracks to Kojima for his approval instead.

Muranaka has previously composed "The Best Is Yet To Come" for Metal Gear Solid and "Can't Say Goodbye to Yesterday" from Metal Gear Solid 2: The Sons of Liberty, and pitched "Don't Be Afraid" as a potential main theme. But the result wasn't considered strong enough for the opening of the game, instead finding its way into the credits of the finished version. So Hibino, who was supposed to be working on something else, took it upon himself to create his own pitch to take to Kojima, to see whether he could give the director what he was looking for.

He tells us, "Since Rika's theme was too mellow and not strong enough as a main theme, and I knew Mr. Kojima wanted more a more James Bond style, I created another one and presented it. Also, as an in-house composer, I knew that if I created a song by myself, we wouldn't need to spend any extra budget on retakes (it would cost more if we outsourced a new song)."

We asked Hibino to give us an insight into what this demo was like and he tells us that it was written using various orchestral sound libraries on a desktop computer. He also gave us a brief insight into his writing process for the song's lyrics, claiming they were meant to reflect the perspectives of both Snake and Eva while also being ambiguous enough elsewhere for others to provide their own interpretation. This tightrope explains why the song jumps from on-the-nose references to eating tree frogs to more profound and resonant lines about self-sacrifice and dedication to a cause that give the track its emotional weight.

I give my life, not for the honour but for you’ are the main lyrics for the song for me...The ‘for you’ is not just for someone you love or someone you think of, it can be about something much bigger.

“'I give my life, not for the honour but for you’ are the main lyrics for the song for me," he tells us. "This [could have] a much, much bigger meaning. The ‘for you’ is not just for someone you love or someone you think of, it can be about something much bigger. For some people, it could be about the whole world, for other people it may be about god (note: Hibino himself is a devout Christian) It’s like a much, much bigger mission you will go through in your life."

Hibino tells us that once he had put the finishing touches to the demo, he eventually presented it to Kojima, who immediately signed off on the track and tasked Rika Muranaka (who was based in the US) with overseeing the production of the song in LA. The demo was then sent over to the States, and Muranaka began the process of assembling a group of musicians to help bring it to life. This first and foremost meant hiring an arranger, so she reached out to Barry Coffing (of MusicSupervisor.com) to see if he knew anyone, and he recommended she get in touch with the experienced composer/arranger/orchestrator named Mark Holden.

The Final Take

Holden was the founder of the company Musiccomm and had a long string of credits in film and TV, which included an Emmy-nominated score for the children's educational health show The Body Works and an Emmy-winning score for the docu-drama Good Luck Mr. Robinson. He was also a huge Bond fan and had a great appreciation for and knowledge of the spy genre and the ingredients that contributed to its iconic sound.

"I always admired [the Dr. No composer] John Barry's work," Holden tells us. "Particularly his score for The Lion In Winter. But the flavors you're referring to go earlier in the Bond franchise [than him], back to Monty Norman's original main title music. Those flavors included the twangy electric guitar, the V, V#, VI, V# chromatic line ascending and descending, big brass, etc. These elements really became part of the DNA of spy movies.

"No one copied notes or rhythms, but the musical DNA was interpolated for the theme music from The Saint starring Roger Moore, as well as the Secret Agent Man main title song for the television series. Especially the distinctive minor chord with a natural 7 and 9. It's actually a very old jazz chord that got a whole new life in the spy genre. Actually, I'd trace the source DNA back to the Peter Gunn main title by Henry Mancini. It's just so deliciously wicked! With regard to the Snake Eater song, that DNA was inherent in the chord progression of the verses."

Inevitably, due to Holden's experience and interests, Muranaka believed that he would be a perfect fit to handle the arrangement of the theme, so she called up the musician, and the two soon got to work on the song.

He explains, "What I recall was receiving a well-executed lead sheet. It contained melody, lyrics, and chord changes. There may have been an audio demo, but I don't remember one. After all, this was some years ago. In any case, I relied on the sheet as source material as well as Rika's verbal direction. As I recall, I produced several iterations of high-comp demos over a number of weeks and perhaps months. The work appeared to be well received, and the direction from Rika was to keep adding orchestral families to the rhythm section production, starting with strings. Eventually, we added trumpet and trombone sections, plus 4 French horns and aux percussion. Perhaps winds - I've forgotten. It was a very elaborate demo/master. My impression was that the project was complete until I received a call from Rika that they wanted the entire thing transcribed for a live orchestra session."

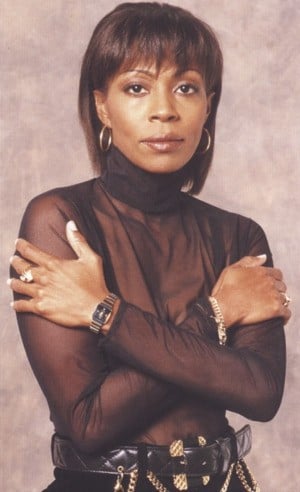

Besides Holden, Muranaka also brought on board her friend, the singer Cynthia Harrell to provide the vocals on the track. Harrell had originally met Muranaka back in the 90s and had kept in touch with the producer over the years, with the two often speaking about different projects that they could potentially work on together (including the track "I Am The Wind" for 1997's Castlevania: Symphony of the Night). So, when Muranaka was given the responsibility of putting together a more complete version of Hibino's demo, she immediately thought of Harrell as being the perfect person to provide the sound they were looking for.

Speaking to Kotaku's Ash Parrish in 2020, Harrell stated, "She asked me to sing. She was like, ‘Cyn, can you come sing this demo for me?’ And I’m like, ‘Okay, it’s fine.’ I think I went and sang it, and I knew it was something special about it. ‘Snake Eater,’ it was something different. A few months later, she called me and she said ‘King Records wants you to do the final version for the game.’ And I said okay, not even really thinking about it and went to do the final version. I show up to the studio—we were in Los Angeles—and I walk in and there’s this huge orchestra and that’s when I knew, this was a big deal.”

As Holden recalls, the orchestra used for the final recording was contracted by Sandy DeCrescent & associates — who was also the contractor for John Williams — and was led by Endre Granat, who is believed to be one of the most recorded concert masters of all time. Before recording, he and Holden worked together to finesse the string bowings and articulations for the track and then set about recording the finished version.

"They read the chart down cold," Holden remembers. "I recall we made the decision to cut the basic track without the trumpets. That section was so powerful we were getting microphone bleed. So we overdubbed the trumpets in a separate pass."

Once it was finished the track was then sent back to both Kojima and Hibino in Japan to evaluate, and was eventually implemented by a member of the sound team at Konami.

What Happened Next

As you will no probably already know if you're reading this, in the years that followed the game's original release on PS2 in 2004, Snake Eater became a much-beloved part of the Metal Gear series, spawning countless covers, live performances, and memes that only served to build its popularity with gamers. For many of its contributors, it's something that they look upon with equal parts shock and amazement, having never expected to still be talking about the song decades later.

Norihiko Hibino, for instance, tells us he "made lots of friends outside of Japan because of this song" and appreciates that many people likely discovered his music through his contributions to the Metal Gear series.

In 2004, Hibino ended up leaving Konami but would continue to work on a number of other games in the series, including Metal Gear Solid: Portable Ops and Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots, as a freelancer with Gem Impact (a production studio he founded).

During this time, he would also start a number of unprofitable musical ventures including a low-cost vocal school and production studio, and would find himself growing somewhat disillusioned with the violent nature of many of the games he was working on as a freelancer. As a result of this growing dissatisfaction, in 2008, Hibino decided to found the Hibino Sound Therapy Lab, to explore the positive effects of music on listeners and its application in therapeutic, palliative, and psychiatric care. He is now behind the popular video game tribute album, Prescription For Sleep, which sees him working with the pianist AYAKI to reimagine classic video game tracks into soothing lullabies.

As for the other key contributors, Muranaka seems to have co-founded a company called VR Innovator in 2016 focusing on the production of VR games, while Holden still works in the film & television industry and occasionally enjoys the odd bit of recognition for his brief involvement with the Metal Gear series.

"I was visiting my brother's family in Houston," he tells us. "I mentioned I'd worked on a computer game called Snake Eater, and my three young nephews went wild with excitement. To my astonishment, they bolted upstairs and returned with action figures and other merchandise from the game. They were LIT! For the remainder of my visit, I was afforded 'rock star' status from the boys. That was fun!"

Harrell, meanwhile, is now mostly retired from professional singing but seems to be enjoying her status as a celebrity in the Metal Gear fandom, delivering a rare live performance of the song at NHK Hall in Tokyo in 2023 and recently appearing at the MGS 2024 fan convention that took place at the Hilton Long Beach, in LA.