In 2005, at the Game Developer's Conference, the Lionhead co-founder Peter Molyneux presented a demo of a project called "The Room" to an audience of curious game journalists and industry personnel.

The demo was the work of a small team inside Lionhead Games, including Alex Evans, Mark Healey, Kareem Ettouney, and Dave Smith — four individuals who would later go on to form Media Molecule. It featured gameplay elements like functional portals, real-time physics, and craftable clay cubes, and was loosely based on the work of the American poet Emily Dickinson poet.

At the time, Molyneux described the project as not a "game with a story" but stated that it "was trying to get people to use a computer game in a different way, to be more about emotion and the emotion of where you are and what you're doing." A live demonstration of the game then followed, set in a series of small rooms, with a piece of music from the Wong Kar Wai movie In The Mood For Love playing over the video feed.

Looking back today, it's a phenomenal demonstration that is truly ahead of its time, but sadly nothing ever became of it. Instead, the project simply disappeared, with everyone involved going on to bigger and better things. Lionhead released Black & White 2 and The Movies, alongside various Fable games, while Healey, Evans, Ettouney, and Smith would depart the studio to strike out on their own. For the longest time, the only remaining artifact from "The Room" was some low-quality footage of Peter Molyneux's talk, but recently Time Extension was able to interview two of its developers (Healey and Evans) and recover some additional materials to finally reveal the secrets of this promising project.

The Keys To The Tower

The story of The Room begins all the way back in 2004, as Fable was wrapping up its development. Both Evans and Healey were working on another game inside Lionhead that would eventually be cancelled called Dimitri, which was an AI experiment named after Peter Molyneux's godson, Dimitri Mavrikakis. Dimitri had been in development for several years and development had started to hit a dead end, causing Evans to start considering his future at Lionhead. As luck would have it though, his time at the studio wasn't through just yet, with a recruitment agency's error leading to a wonderful new opportunity within the company.

As Evans tells Time Extension, "One of the Dimitri projects had sort of wound down, and I wasn't sure what to do, and then a recruitment company faxed my CV to Lionhead, my own employer. Mark Webley, who's like the director of Lionhead, comes running over and goes, 'Alex, I've got this amazing CV of a graphics programmer'. And I'm like, 'Wicked, who is it?' He's like, 'It's you'. And I was like, 'Oh shit'.

"So he took me into a meeting room, and he was like, 'We're not going to give you any more money', but, you know, 'What do you want to stay?' And I was like, ''I don't particularly fancy doing Fable, but I've always wanted to work with Mark. How about you set me and Mark up in a room?'"

At the time, Evans had already worked with Healey at Bullfrog Productions (where Evans had started out making the tea); they had also occasionally collaborated on other early Lionhead titles like the 2001 god-sim Black & White. But Evans wanted the chance to work with Healey on something new and original, where they'd be in full control of their creative destiny. And luckily for him, that's exactly what he got.

Healey was more than happy to join Evans too, considering it to be a good learning opportunity.

"I dabbled with programming," says Healey. "So any opportunity to spend a bit of my lifetime and absorb some of Alex's teachings [was brilliant]. And he was a brilliant teacher. He managed to sort of explain things to me in a way that I think he knew I would understand."

Together, the two developers were given what they now refer to as an "Ivory Tower" inside the studio to work on a brand, new idea, inspired visually by Evans' love of Wong Kar Wai films and a SIGGRAPH talk he had attended in 2001 on Moulin Rouge's post-processing techniques. The idea was to create something moody, rainy, and slightly dilapidated. So, in order to achieve this look, Healey used densely tiled layers of low-res textures to exaggerate the grain of different materials, while Evans developed a crude version of modern tools like a colour look-up table to grade the completed image.

All in all, management was broadly supportive of this arrangement, but as Evans tells us, he couldn't help but feel guilty about receiving this opportunity and like he needed to justify Lionhead's investment in this experimental new project. So he devised a potential argument in case anyone from the company's leadership ever came knocking, working out that it would only cost the studio a relative 0.3 Fable days for a whole year of development on this new title.

Alongside Evans, a couple of other people also joined Evans on the new project. This included the artist Kareem Ettouney who was responsible for much of the game's concept art, as well as a junior programmer called David Smith.

Smith was new to Lionhead at the time and in Evans' opinion, was being drastically underutilized within the company. Having him on the team would be a huge get, so Healey and Evans went to Lionhead boss Peter Molyneux to plead their case — something that turned out to be much easier than they had initially thought.

"Basically, Mark and I gee-d ourselves up to go to Peter's house one evening," says Evans. "We'd play games and have a drink and then you know, drop the question to him, 'Please can we have Dave?' And he knew we were going to ask for somebody.

"He was revving up to say, 'No' basically, 'Fuck off, you can have your Ivory Tower, but you can't have anyone else'. But then I was like, 'Can we have Dave?'. And he was like 'Dave Dave?' He didn't realize how good Dave was. So I was like, 'How much are you paying Dave?' because I'd got no idea. And we found out that Dave was still being paid his starting salary as a fresh graduate. He was the best coder in all of Lionhead, in my opinion, and he was still on his starting salary. So I was like 'Right, thanks very much Peter' [and] we doubled his salary."

According to Evans, Smith brought a new focus to the team. Whereas the other members cared deeply about how the project looked, Smith was more interested in the gameplay side of things, bringing with him an advanced understanding of real-time physics engines, for example. With the team now in place, it started to hammer out ideas for mechanics. And this brings us to something you're probably eager to know about: "What exactly did you do in this game anyway?"

Fun With Portals

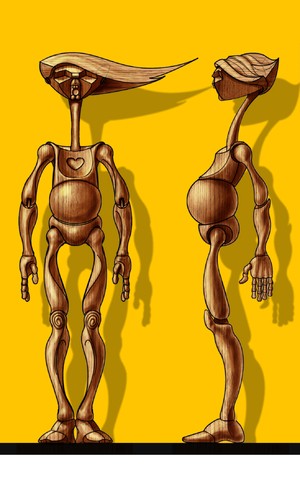

As we were told, the project (which was still to be named) saw players craft a little wooden puppet (called 'Wood Boy') and lead them through a series of rooms with a cursor, showing them different things similar to the AI creature in Black & White. The wooden boy had several different actions it could perform, which they picked up as they traveled from one room to the next. There was even concept art for a little wooden family, as well as a wooden dog companion, that it would most likely encounter on its adventure.

"It's really funny that you messaged us about this," says Evans. "Because I had just watched Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio the day before and I was like reminiscing anyway, because I was like, 'Oh my god, that character apart from the hairstyle looks exactly like what we had in the game.' Mark modeled this really awesome [wooden mannequin], which was all because my engine didn't support skinning. I didn't do any deformation, but we could do rigid pieces. [So] he had this awesome head with this sort of massive quiff [...] and he was going to be the character in the game."

As players led Wood Boy through the game's various rooms, they would need to solve puzzles to help them advance through each area. These puzzles were based on the same core mechanics, including using portals to get around and crafting objects out of clay knobs.

What's especially interesting about this is at this point Valve had yet to release Portal, and the Washington studio Nuclear Monkey Software hadn't even launched the Portal-predecessor Narbacular Drop. In other words, this was cutting-edge stuff at the time, as there was no roadmap or other examples to show how these features could be successfully implemented in a game.

This led to a lot of wild experiments with the portal tech, such as letting players throw objects through different-sized portals to increase/decrease their size and bounce beams of light from one source through a portal into a darker room in order to illuminate it. Physics also played a huge part.

"We had a load of fun game mechanics," says Evans. "If you put two portals, for example, back-to-back on the ground, you'd get buoyancy because basically, things would feel the right amount of gravity depending on how far through the portals they were. So, you could stick two mirrors on the floor and then take a small object and drop it into the portal and it would basically end up bobbing [between them]."

Healey adds, "I remember we spent a lot of time doing those infinite orange-fall things. You'd get one [up here], one [down there], put the orange in and you'd just get this orange falling forever."

As for the crafting side of the game, players were able to create shapes out of clay knobs to produce different objects, similar to Minecraft's recipes. This included things like bowls of fruit and even doors that you could place within the game's world.

"There was a fun game mechanic where there was a recipe for a door," Evans recalls. "So, you'd make a door up and it would appear and you could slap it on the wall and turn a cog on the door; then when you opened it, it was actually a portal that led to a different room."

Healey adds, "Yeah, that was directly inspired by Howl's Moving Castle, which also ended up becoming an inspiration for Little Big Planet."

As Evans explains, the reason why so many of these groundbreaking ideas were possible at the time was that the team didn't necessarily care about things like frame rate or backward compatibility. Instead, it invested in whatever the latest graphics card was, and went to town on trying to make something that would realize its dreams of what video games could eventually be. It's because of this, as the demo progressed, Lionhead as a studio increasingly struggled to really know what to do with the impressive prototype, and the development team started to slow down as they finally tried to pull this cool sandbox of ideas together. That's when Peter Molyneux ended up coming back into the fray.

"We hadn't got a coherent picture of what it was going to be and there wasn't really a plan and there wasn't a game," says Evans. "And then, suddenly, we were like starting to hit the sludge, right, of like slowing down and going 'Oh, I don't know what we're going to do with this' when Peter [Molyneux] came in. He was like, 'I've got to do a talk at GDC against Wil Wright and I've got to do a game based on Emily Dickinson. You've got one week, save me.'

GDC, And What Happened Next?

The team accepted the charismatic studio head's challenge and spent a week transforming what they already had into a demo based on the Emily Dickinson poem "Sweets Hours Have Perished Here". This was a poem that the reclusive Dickinson had written about the second-floor bedroom in which she did most of her writing and where she eventually died at the age of 55. It reads:

"Sweet hours have perished here;

This is a mighty room;

Within its precincts hopes have played,—

Now shadows in the tomb."

The project got a new name — "The Room" — and the team spent a full week polishing what they already had and tweaking the overall theme to brief it was given. The demo added a voiceover narration and some new assets including several paintings of Dickinson. The Fable composer Russell Shaw, meanwhile, handled the sound design and Molyneux did what he did best, suggesting potential ideas (that had yet to be implemented) like the ability to change the hands on the clocks in each room to age certain objects.

Together with Molyneux, the team flew out to GDC in March 2005 to demo the game to a live audience. The talk positioned the prototype as a demonstration of next-generation game design ideas and put an emphasis on real-time physics, portal tech, and the game's crafting systems. But when Molyneux was pressed on a release date, he told journalists in the room that it would likely never see a proper release.

At the time, industry publications like Game Developer covered the demo, while forum users discussed its remarkable technology with both awe and skepticism.

"It was really, obviously sellotaped together," Evans admits, looking back on it now. "Because Peter was like, 'I've got this awesome thing sitting at Lionhead that no one knows what to do with, and this task in a week talking about Emily Dickinson poems.' So we just crunched for a week to produce this bizarre demo, and we enjoyed it. [...] In fact, in the audience at GDC was the Narbacular Drop team who hadn't been signed to Valve yet. So Portal hadn't, you know, been released. They sort of came up to us and said, 'Oh, we're doing a game with Portals', and we were like, 'Wicked that's really cool', so we chatted for a while about Portals."

The team returned from the event the following week, having enjoyed the experience of showing off the game, but the reality was the project had entered into a permanent state of limbo. And to complicate those matters further, Healey and Evans were both on the fence about leaving the company, sensing that something was about to happen due to the number of men in suits being paraded around the office (later revealed to be in preparation for Microsoft's acquisition of the company the following year).

The two started talking about doing a start-up or joining the Washington-based developer Valve, who later published Healey's independent project Ragdoll Kung-Fu on Steam, but there was still one last throw of the dice.

As they were turning these options over in their minds, Molyneux had a bold, new idea for the future of the project that would completely turn it on its head.

He wanted to pitch The Room to Microsoft as a VR Chat-like experience targeted at the MSN messenger install base. At the time, Evans saw this as unrealistic given what the team had already put together, but today he looks back on it in admiration at Molyneux's incredible foresight.

"In some way, that's Peter's genius, right?" Evans says. "15 or 20 years ago, or however long it was, he was like, 'You could have a free program where you can build your own avatar and you can go into this space and you can use portals to build like a web of rooms and spaces and you can play games with each other and you can chat. We will give it away for free and we'll trojan horse it into the Microsoft Messenger sort of audience base', which is like a billion big at that time. At the time, I was like, 'It only runs on high-end GPUs', and he was like, 'Blah, blah, blah, let's go to Seattle and pitch it to them.' [...] It's basically what we call the Metaverse these days, right, or VR Chat. He basically proposed it to us and we didn't see it."

The next thing Evans knew he was in first class on the way to Seattle to pitch the game to Microsoft with Molyneux seated beside him on the same flight. It was here, somewhere over the Atlantic, that the programmer finally worked up the courage to tell the Lionhead co-founder that the team was considering leaving Lionhead, prompting the studio head to beg him to stay "for financial reasons" until the end of the year.

Evans agreed to hold off on making any hasty decisions, and together with Molyneux pitched The Room to a confused group of Microsoft employees, who seem bewildered at the bizarre Emily Dickinson demo and abruptly turned it down. Then, sometime in late 2005, while Healey was away on holiday, and Evans was sitting biding time in the Lionhead studio, an unnamed person entered the studio to tell the team they could leave before Christmas, and to collect their P45s.

"I was like, 'Hang on a second, Mark wants to stay and he's on holiday.'" says Evans. "He was like 'Oh sorry, I've already fired you, you know. Here's your P45, Here's Mark's P45.' That was a little bit intense because we had to go from like nothing [to accelerating] our plans. [...] So we sent an email like, 'Hey Mark is employee number two of Lionhead, and I'm like employee 18 and we're quitting and our last day is tomorrow, bye.' It was a weird, weird week."

"My memory is [Alex] quit for me," says Healey. "That is how I tell the story."

After leaving Lionhead, Healey, together with Evans, David Smith, and Kareem Ettouney, eventually formed the studio Media Molecule in January 2006, developing creative titles such as Little Big Planet, Tearaway, and Dreams for Sony consoles. Microsoft, meanwhile, acquired Lionhead, in April 2006, publishing several of the studio's games like Fable II, Fable III, and Fable: The Journey before closing the company's doors for good in April 2016.

There are a lot of reasons why The Room is worth discussing today, almost two decades since its quiet cancellation. Not only does it represent a vision of what gaming became in the decades following, but it also served as the origin (along with Ragdoll Kung-Fu) of one of the most creative and beloved studios in the UK: Media Molecule.

Today, it's easy to see the DNA of The Room in much of what Media Molecule has released since opening its doors. Little Big Planet's Sackboy, for instance, was created using some of the same texture-layering techniques used in The Room, while Dreams almost feels like a spiritual successor due to its surreal art style and pockets of interconnected creations.

"Looking back on The Room, it was all quite crude what we were doing," says Evans. "But it had so much stuff in it that I think was ahead of the curve. It laid the groundwork for me, Mark, Dave, and Kareem working together, and cemented our friendship. It was like this pivotal moment [...] and such a fun time in my career."