Do you remember the days when your favourite developer might release two, or even three games every year? The Bitmap Brothers launched eight games over four years in the late '80s and early '90s, while Team17 developed 11 games between 1991 and 1994. The relative simplicity of the technology at the time meant it was possible to develop new titles at a machine-gun pace.

Nowadays, of course, it’s rather different. The complexity of modern games means a blockbuster title could take five years or more to complete. Even indie developers might spend years honing a single game. But two Argentinian developers want to return to the whip-crack pace of the '80s and '90s with something they call ‘Pixel Pulps’.

Interactive Pulp Fiction

“The idea is to have three Pixel Pulps out in the first year,” says Nico Saraintaris, one half of Buenos Aires-based LCB Game Studio. “We want to be the pulps of interactive fiction. We really like pulp fiction in the sense of how they approach work, their rhythm in production. Writers not only from the beginning of the 20th century, but if we go further back in time, the penny dreadfuls in the UK, would really understand literature as a trade, as something that you work on, and not as an elevated art form of sorts. We really like to write a lot.”

Fernando Martínez Ruppel is the other half of LCB, and the pair had been working on a bigger game with a bigger team when the coronavirus pandemic hit, which led to its cancellation. “So we had to come up with something that we two could work on,” Nico says. “It had to be fast.”

The key to the studio’s speedy development schedule is simple pixel art graphics. The pair have limited themselves to just nine colours, partly to simplify the process, but also to evoke the nostalgic feel of ZX Spectrum and MS-DOS games of the 1980s. Both of them have fond memories of computer games from the period.

“The ones I enjoyed the most were Sierra and LucasArts graphic adventures,” says Fernando. “But what made me want to make games was Another World. It was a great game… Sam ‘n’ Max and Another World are my two main inspirations.” Nico was similarly into point-and-click adventures, particularly the Indiana Jones games, but he also has fond memories of the 8-bit computers, even though he was only born in 1983. “I had a Spectrum when I was a kid,” he says. “It was from my grandpa: he was like some kind of computer freak in that era, so he had some sort of museum of all the systems in his house.” But Nico struggles to remember any of the Spectrum games he played at the time: his overriding memory is of waiting a long time for them to load and then being frustrated when they crashed – something that no doubt many readers of a certain vintage will sympathise with.

For Fernando, returning to the simple pixel art style of the 1980s has been a refreshing change. “Before, learned to use Blender, and 3D was a new world for me, and it's really cool – but I got tired of it. I wanted to do something closer to… illustration in a more classical way.”

Paranormal Stuff

Nico and Fernando have known each other for around ten years. Fernando has worked as a concept and storyboard artist, while Nico has worked in advertising as well as being a published novelist. “He writes a lot, and I draw a lot, so it was a good match,” says Fernando. Nico adds that the Pixel Pulp concept has very much been a collaborative effort: “It's not like I'm writing and then he's illustrating, or vice versa. He makes some scene or some sequence, and then I write over that, but we work from the get-go as a team.”

Their interests lie firmly in the paranormal: Nico cites the Fortean Times as an “amazing magazine", while Fernando admits to spending much of his time watching YouTube videos on things like the Mandela Effect. Nineties TV shows have left their mark, too. “Twin Peaks and The X Files are always floating around as [our] main inspirations,” says Fernando.

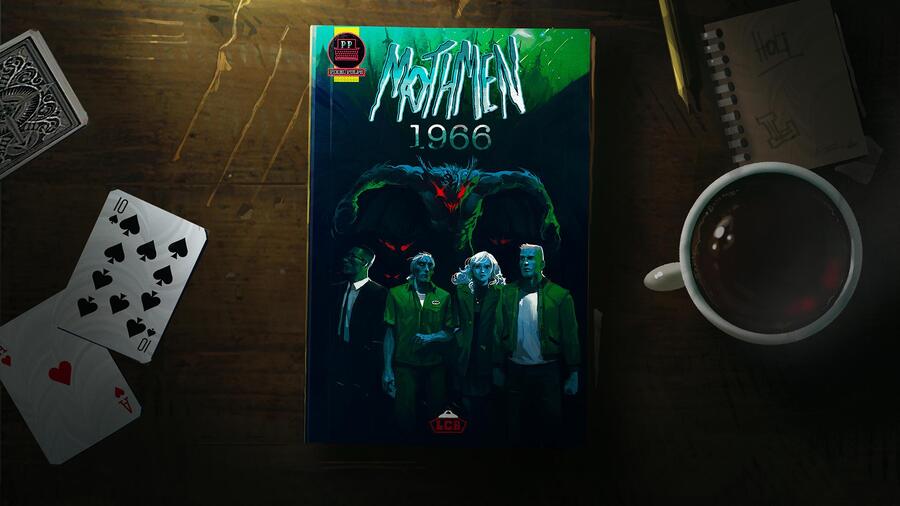

They’ve poured all of these influences into Mothmen 1966, the first of their planned Pixel Pulps. It takes place during the Leonid meteor shower of 1966, which is the starting point for a series of strange occurrences involving winged creatures and men in black. “I had this image of a gas station, inspired by Edward Hopper,” says Fernando of the opening scene. “I wanted to do a pixel art version of that.”

Snatcher Style

In terms of the feel and layout, the pair have been strongly influenced by Hideo Kojima’s Snatcher from 1988: a game that, thanks to its extreme rarity, is talked about far more often than it’s played. “I haven't played Snatcher myself, but I have seen a lot of videos,” says Nico. “We wanted to imagine how Kojima [made] decisions and how he designed his game… Mainly, we took the idea of having the choices pop up from the bottom and having huge text boxes with colours.” They also appreciated Snatcher’s method of having several picture panels on screen at once. “It was kind of dynamic, and we like that.”

Mothmen 1966’s pure black background overlaid with a simple image is highly reminiscent of Snatcher, and helps to give the game a cinematic feel. But Fernando says that several other point-and-click adventures also inspired the game, such as the Gabriel Knight series and Sam ‘n’ Max Hit The Road; Mothmen’s gas station in particular is a reference to the latter. He also says that a 1990 MS-DOS comic book tie-in from Spanish developers Dinamic Software was a big influence for the graphical style. “I remember when doing the game, I thought a lot about a El Capitán Trueno,” says Fernando. “That had a super-limited colour palette, I think it was three colours. I always loved how far they went with the art with so few elements.”

In terms of gameplay, Mothmen 1966 is a visual novel with a handful of interactive mini-games and the odd choice to be made along the way – and like the "Choose Your Own Adventure" books of old, making the wrong choice can lead to an untimely and gruesome demise. The story follows several different characters over one fateful night, and ultimately leads to an ending that will tie it in with later games. “My mum is 66, and she played the game full in, I think, six hours,” says Fernando. “It was nice to see her finish the story, and not be overwhelmed by the puzzles.”

Ultimately, the choice to limit the palette and scope of the game has resulted in a pulp-fiction game that is not only quick to produce but also incredibly visually distinctive, evoking an era in which underpowered computers struggled to crank out more than a handful of colours. “We love constraints, not only in art, but also game design,” says Nico. Sometimes, less is more.

Comments 1

I've been distracted with trophy hunting lately but have Mothman ready to go on the Switch. I'm so here for the Pixel Pulps!

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...