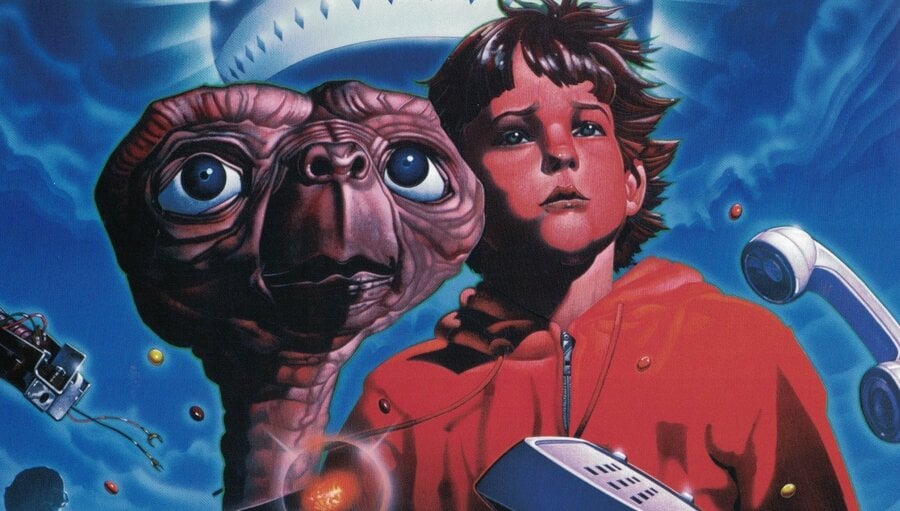

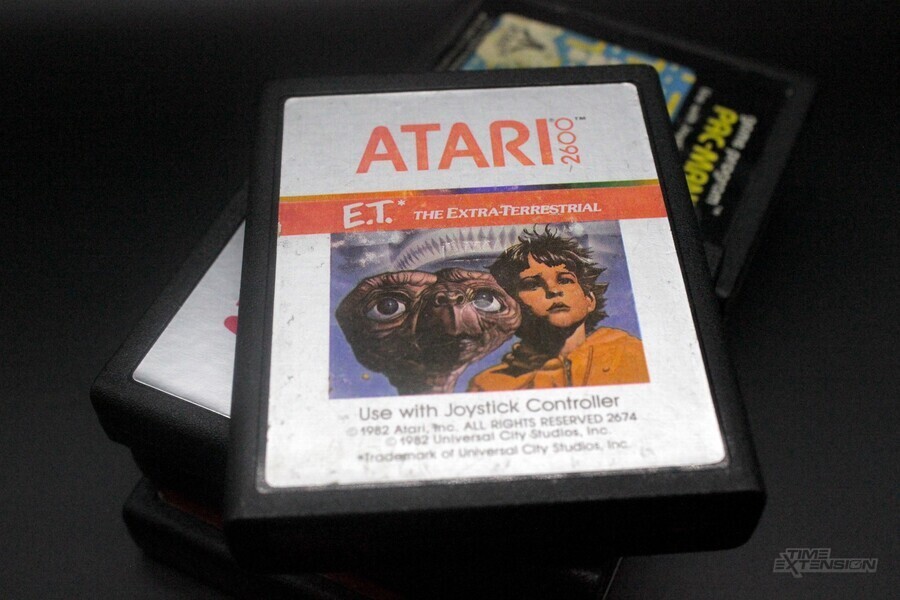

On Tuesday, July 27th, 1982, the video game designer/programmer Howard Scott Warshaw accepted a call from his bosses at Atari, asking him to put together the video game tie-in to Steven Spielberg's latest blockbuster E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial for the Atari 2600. He had previously worked with Spielberg on a successful adaptation of the Indiana Jones film Raiders of the Lost Ark, but this time around, there was a catch; he had just 5 weeks in which to do it.

Young and eager to please, he jumped at the opportunity, but E.T. proved to be a major disappointment for players. In the decades following, it appeared on countless "worst video game” lists, with some even blaming it for the temporary death of the North American video game industry. There was even a popular urban legend that sprung up in its wake, which claimed that Atari had dumped a large amount of unsold copies in the desert after being left with millions in useless stock. For the longest time, nobody could separate the facts from fiction. Then, in 2014, a group of filmmakers excavated the burial site proving once and for all that the story was, in fact, true (albeit slightly more complicated than the legend had let on).

In the past, we've spoken to Howard Scott Warshaw twice — once in 2015 and again in 2023 — with our conversations covering the development and fallout of E.T., as well as the rest of his time at Atari. These interviews shed a bit more light on his unusual entry into game development, the creation of his first two hits Yars’ Revenge and Raiders of the Lost Ark, and his thoughts on the E.T. situation all these years later. What follows is the incredible story of Warshaw’s career and the game that would eventually change his life forever.

Avoiding Computers Like The Plague

Growing up in New Jersey, Warshaw had absolutely no interest in video games, or computers for that matter. Instead, he spent much of his time playing poker and tennis and looking for dates. In the past, he had owned a Magnavox Odyssey — an early video game console featuring a bunch of simple games — but he quickly grew tired of it. He also occasionally followed his friends down to the local arcade but it never occurred to him to actually play the machines himself; he was just happy to spectate.

"I actually avoided computers like the plague," he tells us. "In the mid-to-late 70s, computers weren’t everywhere. They were on the rise. Everybody was aware of them, but especially in schools/universities there weren’t many computer science curriculums for computer departments. And in point of fact, where I went to school, they were just beginning to look at that sort of thing. I actually had an early opportunity, where at my high school in New Jersey, we had a remote terminal that was connected to a computer at Rutgers University. There were a number of my peers who were using that terminal to practice programming and connect with the computer at Rutgers, and I never did. I mean, I had friends that were doing it, it was always all around me, but I always avoided it. I just thought, ‘Computers? I don’t want to deal with that.'"

At this point, if you're still reading, you're probably wondering, what changed? Well, the answer to that lies in a brief conversation he had with a professor at Tulane University in New Orleans, where he had enrolled in order to study Economics. His tutor told him that he would need "something with computers" if he was to get an Economics job, so Warshaw immediately took heed of the advice and headed down to the university's computer department in the middle of the term to try and finagle his way onto a course. He pulled one of the teachers aside and explained his situation to them.

"I think he kind of thought I was kidding or something because this was week 7 of a 14-week semester and I wanted to pick up the course," Warshaw tells us. "He was like, ‘Well, okay!’ He told me where to get the book and I got it, and that night I did the entire first half of the course. I just went through the book and it just totally made sense to me; it was a revelation. And this thing that I had been avoiding for all these years turned out to be the magic answer for me academically. What I really enjoy [doing] is solving puzzles and things like that. And I realized that computer science was very much that."

After receiving his degree in Economics and Mathematics from Tulane, Warshaw stayed on in education to get a Master of Engineering in Computer Engineering. He then left Tulane in 1979 and landed himself a well-paid job fresh out of University working at the technology company Hewlett-Packard.

Sadly, though, his introduction to the world of programming wasn't quite what he had anticipated.

"I got a job at Hewlett Packard working in their computer division, and all the passion that I had found, and all the wonder that I had found in computers, was lost. It was like a desert. And I couldn’t believe it. Where did all this go? How could all this great stuff that I love so much just disappear? [...] Everything had slowed down. It sort of felt like a software pasture where programmers go to get ready to die."

Bored at work, Warshaw started acting out and playing pranks, leading one of his co-workers to tell him about a company he knew where such antics were commonplace. That company was Atari, a Silicon Valley-based video game developer and manufacturer that was already making headlines for its miraculous success story.

"I wasn't into video games," says Warshaw. "But I knew Atari made games and I was into the kind of programming that they did there. When I found out it was a wild place to work, I went and just pushed my way in to get some interviews. The more I learned about working at Atari, the more I realized this is where they are doing the kind of programming I like to do. This is where it is happening."

Yars' Revenge

To get the job at Atari, Warshaw went through a long series of interviews with a bunch of Atari employees including the consumer software manager Dennis Koble and programmers Bob Smith and Carla Meninsky, to name just a few.

The topics of these conversations included everything from casual discussions about Warshaw's lifestyle and attitude toward drug-taking to programming questions in order to gauge his abilities. For the young programmer, who had been fed up with the straight-laced environment at Hewlett-Packard, these discussions only strengthened his resolve to want to work at Atari. But after the process was over, the news wasn't exactly what he was hoping for.

"They rejected me," he tells us. "Ultimately, what they said was, ‘We’re not sure you would fit in here’ because they thought I was too straight to work at Atari. And that later became a big joke at Atari because I was one of the most outrageous characters at Atari. But the thing is I was working at Hewlett-Packard at the time. I came from a very professional environment and when I go to an interview somewhere I adopt a very professional and conservative demeanor. And they were looking for wild people. I said, ‘Look, you’ve got to give me a chance to be in this environment and I will show you I can fit in.’ I just begged him to give me a chance, any chance."

After much negotiating, Warshaw managed to successfully talk his way into the job. He was given a book on how to program games for the Atari 2600 and told to report to Atari's Consumer Electronics offices at 1272 Borregas Avenue on January 12th, 1981. Upon arriving, Warshaw was placed in the same office as Tod Frye and Rob Zdybel and was then given his first assignment at the company: porting Cinematronics' Star Castle to the Atari VCS (another name for the Atari 2600).

Star Castle, in case you're in need of a quick refresher, is a multi-directional shooter that was released in the arcades back in 1980. In it, players control a small ship and must blast away a bunch of defenses that are protecting a cannon located at the center of the screen. According to Warshaw, it was "a worst-case scenario for the hardware on the VCS" and he wasn't particularly keen on his first title simply being a copy of someone else's work. So, ironically, after telling his bosses he would do whatever it takes to work at the company, he immediately got to work on trying to change the assignment.

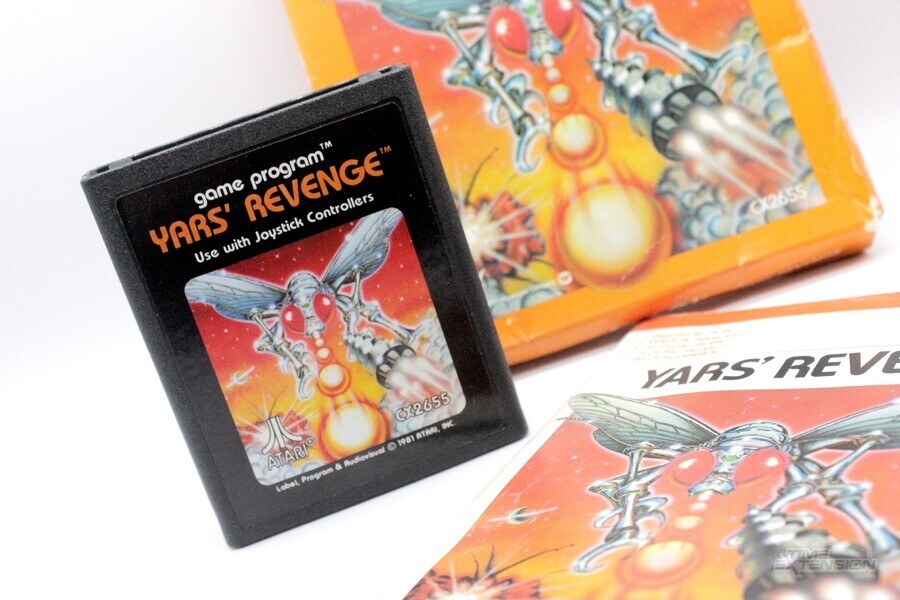

He pitched his manager at the time Dennis Koble on creating something original that would incorporate many of the same elements as Star Castle, and surprisingly, Koble agreed. The working title for this project became Time Freeze (later to be changed to Yars' Revenge as a play on the name of the then Atari president Ray Kassar).

Yars' Revenge carried over many of the same principles as Star Castle. Players once again controlled an avatar on the screen and destroyed a bunch of shields in order to get a clean shot at a single enemy. This time around, though, the target was positioned on the far right of the screen, with the player having to unlock a special cannon in order to destroy it. For the young programmer, it was an exercise in overcoming limitations, with the Atari 2600 only having 128 bytes of RAM and 4K memory for the entire game.

"I just wanted to make something amazing," Warshaw tells us. "Literally, that was my constant. I want to do something that’s a really cool game. And I want to think of everything that I can do to distinguish this product and make it special."

He continues, "It’s funny because I have a Masters in Computer Engineering but I’ve always told people I really think it’s my degree in Economics that’s really helped me be a good programmer. Economics is about allocating scarce resources, and if there was ever a scarce resource it was the 2600. I mean, nowadays data structures are larger than the entire game was then. So, I always tried to find the super slickest, cheapest way of doing something."

Warshaw came up with a bunch of creative solutions in order to add to the experience for players. This included using the game's code to create the glittery Ion Zone at the center of the screen and the full-screen explosion that appears after completing each level. He also put together an original backstory for the game too — a rarity for Atari 2600 titles at the time that had up to that point mostly been conversions of popular arcade hits.

In total, Yars' Revenge took Warshaw seven months to complete, but the road to release proved to be much longer, with the game being subject to constant tests within Atari. This all came about thanks to an unnamed individual within the company who had seemingly taken against the project.

"There was someone in the company who just didn’t believe in it," Warshaw says. "They just felt the game had some issues and problems and they kept trying to point out: ‘Hey, look, there are some issues with this game, and so we shouldn’t just put this out, it needs to be fixed.’ Now, the problem was everybody internally loved the game and some of the initial testing that we had done on the game was indicating that it was doing very well and people loved the game. But there was someone who really just for whatever reason — and I don’t know completely what that reason is — had a problem with the game. Or with me. I don’t know."

Following months of testing, the fate of the game hinged on a final playtest in Seattle that pitted Yars' Revenge against the Atari 2600 port of Missile Command, the number-one title on the VCS at the time. Warshaw believed that this was "the kiss of death", but to his surprise Yars’ won, and the powers that be were eventually forced to release the game.

"That was astounding," Warshaw says. "After that, they finally said, ‘We can release it now.’ Whoever was complaining, I think they just lost credibility at that point. They weren’t worried about the complaints anymore, they just wanted the game out, and it went out."

When Yars' Revenge was released in May 1982, it was an instant hit for Atari, selling over a million copies. However, there was no time for Warshaw to celebrate behind the scenes, as he was already hard at work on his second game, an experience that would involve meeting one of his personal heroes.

Meeting Spielberg & Raiders

In June 1981, Steven Spielberg released Raiders of the Lost Ark in cinemas, a film about a globetrotting archaeologist inspired by early 20th-century adventure serials. It was a box office smash, becoming the highest-grossing film of that year, and led Atari to immediately snap up the rights from Lucasfilm to create a video game tie-in.

Being a film buff and fan of Spielberg's work, Warshaw put himself forward for the project and soon found himself on a commercial flight from San Jose to Burbank, to meet with the famous director and essentially "audition" for the role. After a 5-hour delay, in which he roamed around the Warner Studios' lot geeking out over everything he saw there, he finally got the chance to sit down with the filmmaker in his office and start brainstorming ideas. Together, the pair played a version of Yars' Revenge and talked about ways of converting Raiders into a game. Then Warshaw decided to let Spielberg in on a little theory that he had been developing about the director.

He tells Time Extension, "I said to him, ‘You know, Steven, I have a theory that you’re actually an alien yourself.’ And I laid out this whole idea I had that aliens aren’t just going to show up and go, 'Here we are!' That they’re going to send an advanced team to culturalize us and get us ready to meet them. And so, I said I figured that was what was going on, and what they would do is that they would make movies that showed aliens in a positive light, like Close Encounters."

When Warshaw was done telling Spielberg his theory, the director didn't respond, but he also didn't kick him out of his office either, which he took to be a good sign. The two parted on good terms. Then the next day, Warshaw returned to Atari to find out that Spielberg had actually called ahead and told them that "This is the guy". To this day, he still thinks that it was his alien theory that landed him the gig, though after Spielberg directed War of the Worlds in 2005, he no longer suspects Spielberg of working on behalf of an extra-terrestrial greeting committee.

Development on the video game adaptation of Raiders started shortly after this meeting (in the middle of 1981), with Warshaw's idea being to build on the groundbreaking work of the programmer Warren Robinett and his 1980 Atari 2600 title Adventure. In Raiders, players controlled Indiana Jones and walked around different environments collecting items and solving puzzles. However, unlike Adventure, this time players could carry multiple items at a time, thanks to a two-joystick control scheme. Warshaw was also permitted to use 8K of memory on the game, a considerable improvement on the 2K used by Robinett.

"My goal with Raiders was to make a huge game," says Warshaw. "If you just count the number of screens, it’s not the most screens in any game, but if you count really unique scenes and gameplay per scenario, I think it is one of the largest games on the VCS. I really appreciated the significance of what Warren Robinett had done with Adventure. But now, it was my turn to do an adventure game. And I thought if I’m going to do an adventure game, I want to do something that’s worth doing, that people will notice and go, ‘Wow’."

Warshaw worked on Raiders for a total of 10 months, occasionally being joined by the artist/animator Jerome Domurat. During that time, he started to dress like Indiana Jones to get into the mind of the character and even took to carrying a bullwhip around the halls of the office, cracking it as he walked. He jokingly called this process, "R&D" — "Research and Discipline" and even recalls a couple of new hires walking in the other direction when they spotted him in the corridors.

After the game was finished, Atari planned to give Spielberg a demo of the game at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June 1982, and again, Warshaw volunteered to do the honours. Atari sent him to a nearby video studio to record a playthrough of the game with commentary, which ended up consisting of a single take lasting roughly 12 minutes in total. Then, after recording was completed, he went and personally hand-delivered the tape to Spielberg himself.

"He sat there and he just watched it all the way through with my narration," says Warshaw. "And, at the end of it, he looked at me and he said, ‘You know, it feels exactly like a movie!’ And that just blew my mind. That I had put together a game that was themed on a movie, and when he played the demo of the game, Stephen Spielberg felt that it was just like a movie. That was one of the single most gratifying moments of my life. So, I’m still grateful to him for that."

With Spielberg satisfied, Raiders of the Lost Ark eventually came out in November 1982 and was another success for Atari, again selling over a million. Based on this, Warshaw was tapped to do the next adaptation of a Spielberg film, but things wouldn't go quite so smoothly this time around.

The Worst Game Ever?

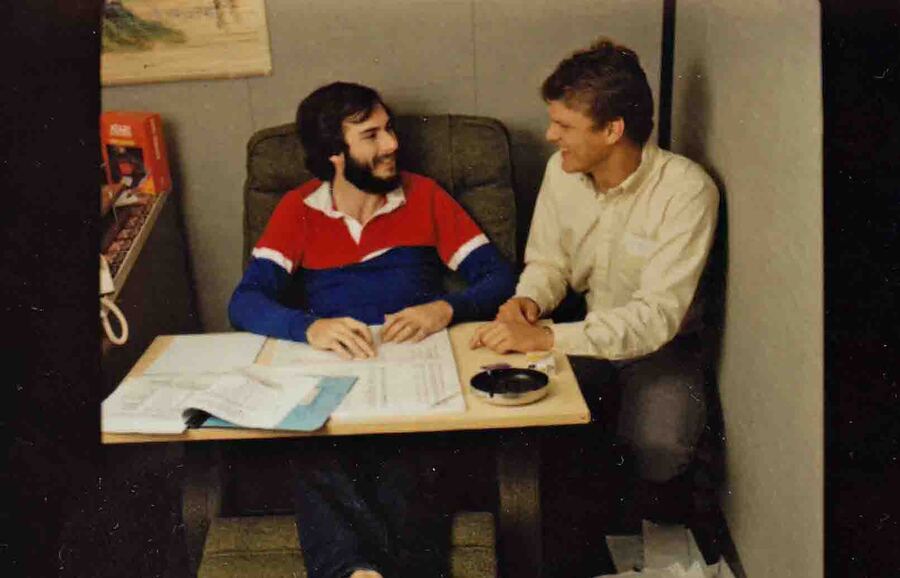

On a Tuesday, in July 1982, Warshaw was sitting in an office with his friend and collaborator Jerome Domurat when he received a call from Ray Kassar, the head honcho at Atari. Kassar had only ever interacted with Warshaw on a couple of occasions in the past, so the programmer knew this must be important — and it was. Steven Spielberg had agreed to let Atari do a video game of his latest film E.T. and had personally requested Warshaw be the one to make it.

Kassar asked Warshaw if it would be possible to turn the game around in just five weeks (at the time, the average Atari game took 5 months to develop). And despite the warning signs, Warshaw agreed. That Thursday, he then found himself on a private jet, on his way to meet Spielberg in order to pitch an idea for its design.

The plan he came up with for the game was all about capturing the emotional tone of the film. One way he tried to do this was by making certain characters react differently to E.T. The FBI agent, for instance, is interested in what you have, and steals your possessions; whereas the scientist is more interested in your identity, kidnapping you and taking you back to the city. The ultimate goal of the game was to collect three pieces of an interplanetary telephone hidden across several pits and reach the landing spot in order to "phone home".

Excited about the opportunity to work with Spielberg again, Warshaw presented his idea to the director, but he wasn't immediately enthusiastic. Instead, he suggested something else that took Warshaw by surprise: making a knock-off of Pac-Man.

Warshaw tells us, "I was really dumbfounded. There was just something about that moment. I had hoped that I had established myself as a creative innovator with Stephen Spielberg. And to have him suggest to me ‘Okay, maybe you should just do a knock-off’, there was something really weird to me. I had this impulse when he said that, to say to him, ‘Well, gee Stephen, couldn’t you do something more like The Day the Earth Stood Still?’ But, you know, this was Stephen Spielberg, and I didn't say that to him. I just said, ‘Well, you know Stephen, I don’t know if we have the time to do a knock-off. I don’t know if that’s a good idea. Shouldn’t we do something more unique to this game?"

Spielberg eventually agreed with Warshaw and a completion date was set for September 1st, 1982, with the game expected to hit store shelves that December. Remarkably, Warshaw managed to stick to this deadline, and when E.T. hit the market later in the year, the initial reports inside Atari were positive. This good fortune wouldn't last long, however.

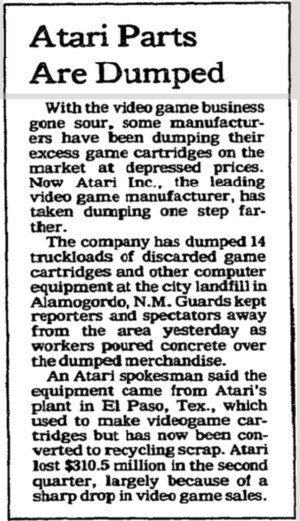

The following year, the San Francisco Examiner labelled E.T. a "flop", estimating that Atari had been left with over $40 million worth of unsold cartridges, thanks to a combination of overproduction and an abundance of returns. The game's failure couldn’t have come at a worse time for the company, with Atari's parent company Warner announcing in December of 1982 that sales of Atari’s home video games had taken a turn for the worst. In 1983, to save costs, Atari started to close its domestic manufacturing plants, leaving the company with a large amount of unsold inventory it would need to dispose of. This eventually led Atari to start dumping truckloads of cartridges and equipment in a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico throughout September of that year.

The Atari burial and the company's fall from grace coincided with a dramatic downturn in the North American console market. By the end of the year, the chairman of the video game developer Imagic William Grubb, told The New York Times at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show (as syndicated by The Billings Gazette): "For this Industry, 1983 was the year of humility." Roger Sharpe, the editor of Video Games magazine, meanwhile, added: “The phenomenon is over. The industry dug its own grave by thinking that all you had to do was put something in a box and the public would buy it. The question is where the industry will stabilize.”

Over the decades that followed, people began attributing the crash solely to E.T., with this version of events being perpetuated in the gaming media and early YouTube videos. E.T. started appearing in countless "worst video game" lists, with its infamy growing with each mention. So what did Warshaw make of all this? Well, for a while, he responded to it all with his trademark sense of humour, joking about the game in interviews and occasionally expressing his disappointment whenever a publication left E.T. off its 'worst video game' lists. But he also admitted to being a bit self-conscious about the whole ordeal.

In 2014, however, this all changed when a filmmaker named Zak Penn directed a myth-busting documentary about E.T., called Atari: Game Over. The documentary saw a crew of construction workers gain permission to excavate the Alamogordo landfill where the game was supposedly dumped, with Penn also interviewing celebrity gamers, industry professionals, and Warshaw himself to find out the truth about E.T. and its legacy. The experience was hugely cathartic for Warshaw, removing an emotional weight he had been carrying around for years.

"To this day, every time I see Atari: Game Over, I get emotional," says Warshaw. "There’s the thing of being exonerated for E.T., and that’s one thing, but there’s an aspect to that movie where I really get to hear people I respect and honour appreciating the work that I did and the contribution that I made. So, there was this thing that I was carrying for a long time, that I always sort of carried with humour and I thought it was fun and I learned to make fun of it, but I didn’t realize how much I missed some of the appreciation until I actually saw it and seeing that is just a deeply meaningful experience. I am incredibly grateful to Zak Penn and to Simon and Jonathan Chinn, the producers, for putting together something that was very healing in my life, quite honestly. It meant a lot to me and had a tremendous impact on me."

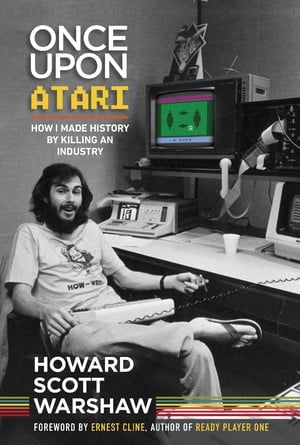

Since Atari: Game Over, Warshaw has gradually come to terms with his own part in the E.T. story, even writing a memoir about the experience, called Once Upon Atari: How I Made History By Killing An Industry, which was released three years ago. The book is written in Warshaw's own voice and sees him finally embracing his important yet slightly uncomfortable role in the history of the video game industry.

"I never really felt complete with the story until I saw the Atari: Game Over documentary," says Warshaw. "Once Upon Atari is very much my memoir — that includes a lot of Atari stories and commentary on the whole Atari trip. Because I had a big impact on Atari, but Atari had a much bigger impact on me. And it still does. It still resonates in my life."