We've already covered how academia is ignored by the press. Your author first encountered the world of video game academia in 2014, when invited to give a keynote to a packed symposium hall in Montreal, Canada. The topic was on preservation. The event had many fascinating talks, a curated selection of which was published the following year.

One of the other talks to catch this author's interest was by Mia Consalvo regarding Faunasphere, a casual MMO that launched in 2009 and closed 2011. Not for the game itself, but because the research called to mind the work of Dian Fossey - perhaps you've seen the film, Gorillas in the Mist? This online community would soon cease to exist, and this lone academic was embedded, observing, making notes, recording interactions, interviewing, seeking a contextual understanding. How many casual participants were even aware they were being watched? Had I been watched by academics at some point? (Are you being watched while reading this?) It left an impression - researchers will observe and bring to light even the most obscure or forgotten of people!

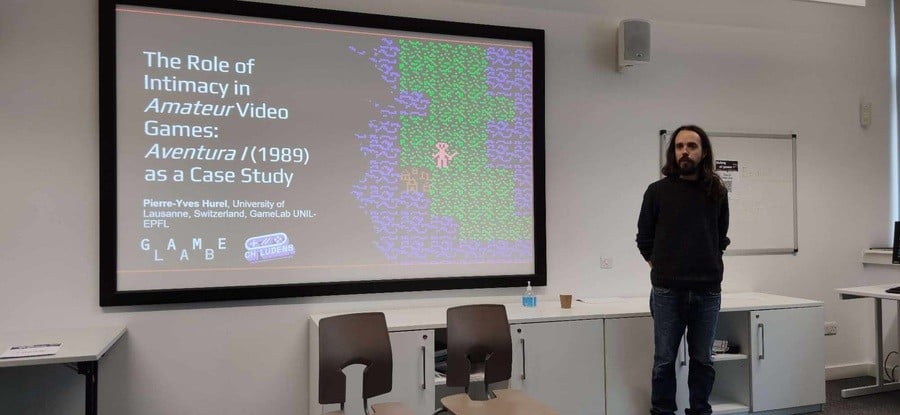

Entering the hitherto unknown world of academia planted a seed, to bring any and all intriguing research to the mainstream. A decade later of banging this drum, to zero interest from the press, I attended a talk by Pierre-Yves Hurel which captivated in a similar way. Hurel is involved with a lot of research related to Swiss video games, and gave two talks at the conference, but this light-hearted missing person's investigation shows that scholars also have fun!

Hurel based his PhD on the study of amateur works; with regards to doujin in Japan he conducted two interviews. A bold choice given how overwhelmingly complicated the history of amateur games are in Japan. In the world of games "amateur" efforts sit separately from indie, in that they're done for fun, without commercial interests (though some do cross-over, as with Cave Story). Given the incalculable volume of amateur games, plus the demo scene, and how fragmentary our understanding is, Hurel seeks to better document this ecosphere.

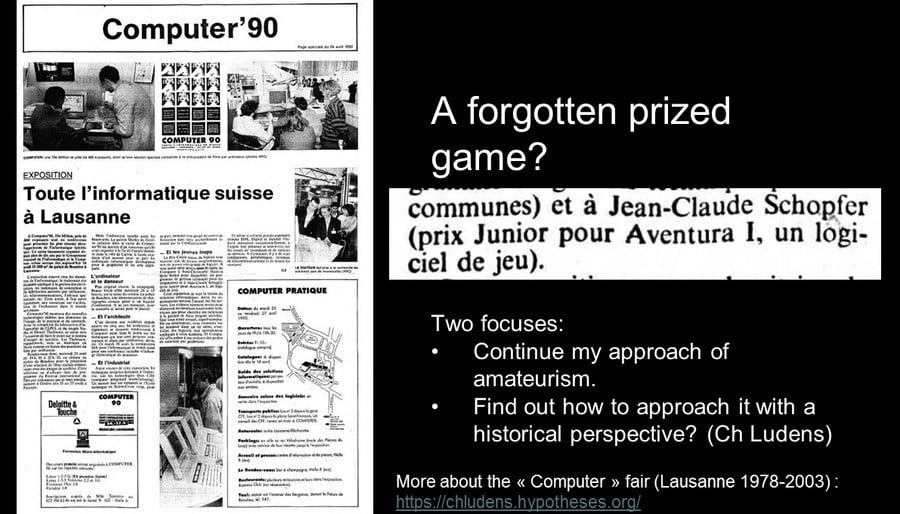

Browsing the April 1990 issue of Journal de Genève, a Swiss newspaper, Hurel saw a piece of news on the Computer 90 Expo: "The Crédit Suisse Software Prize supports either young programmers or young software companies. It will award this year [...] to Jean-Claude Schopfer (Junior prize for Aventura I, gaming software)."

Now this was interesting! A 14-year-old Swiss resident created an amateur game for the Atari ST, won a prize from the bank Crédit Suisse, and then promptly vanished. The title of the game - affixed with "I" - also implied there was to be a sequel. Is this game a forgotten treasure? What happened to the promised follow-ups? More importantly, what happened to Jean-Claude Schopfer?

Step one of the investigation was acquiring the game (it's online). Aventura I is an RPG which mimics popular games of the time, Ultima IV and Dungeon Master. Hurel played for 10 hours - he's uncertain if it can even be completed, since it gets very difficult near the end. But he drew maps to navigate the dungeons, and analysed the gameplay loop, comparing it to its contemporaries. There's also a crash bug when one dies - he's unsure if this is due to the coding or emulation.

The storyline involves the player-created character (male or female, stats, etc.) exploring a real world location in Switzerland, an abandoned building called Le Manoir Maudit (since demolished). A digitised photo of the building and its name features prominently on the game screen. The player after entering this building is magically whisked away to a fantasy dimension, and so the adventure begins!

Next Hurel tracked down Schopfer, contacted him, and met in-person to conduct an interview. Schopfer indeed had completed only one game in his life. Today, over 30 years later, he was a programmer in the banking sector. He said to Hurel: "My dream as a kid was to become a writer, not an IT specialist. We often have two preferred paths, and then we choose... That's life."

His programming had been self-taught on the family computer, with Aventura I using 8000 lines of GFA BASIC. On reflection, Schopfer said: "The music was not good, and I'm bad at drawing. But my aim was to make something. I was about to do everything better with Aventura II."

Sadly a technical failure resulted in much of the sequel's work being lost. Schopfer was also adamant about not sharing the source code, since he was somewhat embarrassed by its amateurishness.

Hurel's talk conveyed that amateur games were the embodiment of intimacy. This wasn't something with commercial considerations in mind. It was a deeply personal narrative, inspired by what the author enjoyed and grew up with; much of it borrows from games he enjoyed, comics he read, music he listened to. Plus, of course, Le Manoir Maudit.

Hurel discovered that for Schopfer and his friends, this local abandoned building had been a focus of attention. Schopfer made it part of his very personal games project. The windows were missing and graffiti covered the walls, but these young teenagers would get up to mischief there. When the building came to be demolished, Schopfer and friends made a short film. It showed the group planting explosives in the building, throwing dynamite through windows, and then spliced this footage with a far-off recording of the actual demolition. One of the gang is even shown "inside" when it goes off, later breaking free from the ruins. It's only three minutes long, but to be honest, the editing is impressive for teenagers in the mid-1990s. Also the unlicensed use of "Save Us" by German power metal band Helloween is a nice touch. (Hurel shared it, though he feels uncomfortable making it widely available without the author's permission.)

In this way Schopfer's work is an example of transmedia - something which spans different mediums. A commercial example from that time would be Street Fighter II, with its games, comics, and movie. But this was produced, quite literally, by a kid. In conjunction with his amateur game, this amateur film is today like a slice of regional history. It evokes a nostalgia for the whimsical little projects we all tried in our youth.

Ultimately, as Schopfer explained, there was uncertainty about being a game developer in Switzerland at this time. Would it have been a viable vocation? He also laments the content of his game, suggesting that as a more culturally developed adult he would have made it differently.

But would that necessarily be better? Part of the charm of unearthing ancient and forgotten games is seeing how an author's personality is infused within. Hurel's investigation resonated on a personal level because I had done something similar, many years ago, with Professor Ishikawa. He'd made two fantastic games while in high school, then vanished. Translating his name into English I tracked him down to the university where he lectured, later interviewing him in Japan.

It's not just hobbyist or forgotten developers either. At the 2024 conference Darren Berkland and Orcun Can gave a talk, "Archaeology of the Devlog", where they had spent considerable time exploring and dissecting the devlogs of Derek Yu (Spelunky), Dillon Rogers (Gloomwood), and Ben DevDuck (Dauphin). It shows how at any given time, anyone might be under observation.

From academics such as Consalvo through to Hurel, and all others, plus writers such as myself, nothing is ever truly forgotten. Did you ever put out an amateur game, demo, song, comic - or anything really - like a message in a bottle thrown out to sea? Have you ever posted on an internet forum or comments section? Because if so there's the chance you're now part of an anthropological or academic study somewhere.

(Schopfer actually has a little website where you can download his game.)