Following the remarkable success of Myst in 1993, the designers and brothers Robyn and Rand Miller were dealt the almost impossible task of coming up with a sequel that lived up to the incredible reputation of its award-winning predecessor. What followed after was an ambitious (and costly) four-year-long development cycle that saw the brothers expand their studio Cyan, and partner with the former Aladdin production designer Richard Vander Wende, to create a much larger and more visually impressive world.

Riven, as the sequel was eventually called, focused on the actions of an unnamed character who is tasked with exploring a bunch of deteriorating islands to free Catherine (the wife of Atrus from the first game) and to put a stop to a tyrannical leader named Gehn (who is Atrus's father). It was released for Windows PCs and Macs in 1997 and proved to be another success with critics and fans. Although, it arguably had less of an overall impact on mainstream popular culture, in retrospect.

The game has seen various ports and rereleases over the years, but, back in 2022, Cyan Worlds sparked some major excitement among its online fanbase when it announced that it was working on a from-the-ground-up remake of the title, which would abandon the point-and-click interface of the original for "a fully traversable 3D space".

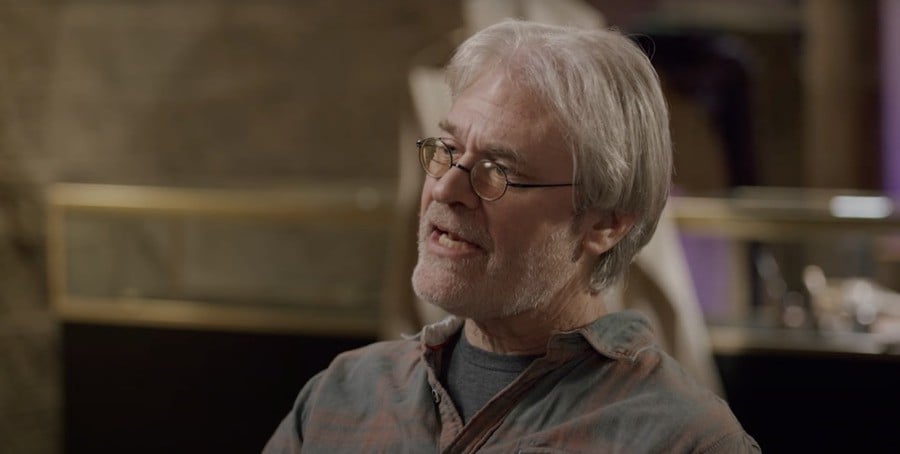

This finally arrived earlier this week, on June 25th, across PC (Steam, GOG), PCVR (Meta Quest), and Mac, and has been getting some incredible reviews from critics so far. As a result, Time Extension wanted to reach out to Cyan's Rand Miller to hear more about the journey of remaking Riven and how the studio was able to remake the game with most of the original assets being lost to time.

Time Extension: First of all, congratulations on the release. How is the team feeling with all of the incredible feedback? The reviews so far have all been great. Have you had the opportunity to all get-together with the team and reflect on what people have been saying?

Rand Miller: Not really. I mean, there are a lot of people at the office and a lot of people on Slack — mainly on Slack. And we did have a release party, but it was a little bit before we could really see the response. So the Slack channels are buzzing because, you know, we love it, but I think very quickly we had to also go into response mode. When you suddenly move from your internal QA testers to the teeming masses testing your product, they find things that you didn't realize were there.

So immediately after you launch we've learned over the years that we have to shut down all vacations and celebrations and just kind of really hit it hard on the patches to try and get the things we didn't realize were in there. So probably a week from now we'll have a little more relaxed feeling at the office and take a breath and celebrate a little bit more.

But yeah, we've been so surprised. We didn't know. As you can imagine, with Riven being so well respected — I guess, is a good way to put it — through the years, and not having touched it, to go in and make these changes was... We weren't sure. I mean, we're fans of it too, so we were looking at it like, 'Well, man, we would like this if we were playing it.' But there was no way to know for sure until it was in the wild. And so to follow up on that same question, there is — in spite of the fact that we're working hard now on fixing little things — there's this huge sigh of relief, like, 'Oh, they like it, they really like it', which is great.

Time Extension: When was the decision made to remake the game? Could you give me an idea of how you were feeling going back to it?

Rand Miller: I think we knew, we've known for years, that at some point we would like to jump back into redoing Riven, but it was with fear and trepidation. I think we put it off knowing that it also was very special and we wanted to do it right. The fact that Starry Expanse Project had been working on a fan-created version of it was fun. It was interesting to watch them. It was a lot of years that they worked on stuff and different 3D engines, and their take was to do it exactly the same, or to try and keep it as precisely like the original as possible.

So it was probably four years ago — four or five years ago — that we really started thinking, 'Okay, we've turned a corner, the engines look really good, like they could do this'. And the first response, our first thoughts, were 'Well we're just going to do a remake exactly the same. We won't change it either. It looks like that's what people would want. Everybody loves it.' And then when Richard, my brother Robin, and I sat down in some early meetings we decided to do what is always fun for creatives and just blue sky.

Like, 'Well, what if we did change it? What would we do? What are the things that were inconsistencies that we could fix?' And once we opened the door to that, there were certain threads that we pulled on that started to unravel little things in the original that we thought might be really interesting to double down on. 'Well, what if we separated the architecture between the inhabitants of the island and Gehn? What if we really spelled that out a little bit more? And why was the submarine in this location? All the little things that seemed okay in the original, but even as fans were looking at them, they were wondering about those things.

We had some dissenters even at the office [...] There's a lot of people, even at the office, who were like, 'No, no, no, don't mess with Riven'. But as we were able to present it and present the reasons why we did certain things, they started to come along.

We had some dissenters even at the office. I mean, we're small and scrappy, and the people who work here have a love for our products. And so there's a lot of people, even at the office, who were like, 'No, no, no, don't mess with Riven'. But as we were able to present it and present the reasons why we did certain things, they started to come along. And as we started to build those things, I think we started to build a little bit of excitement internally as well, like, 'Oh, this could be something special.'

I think the thing that really excited us about this potential more than anything was I kept seeing on Reddit, when people found out we were doing a Riven remake, there was a consistent thread of comments that said something like, 'Man, I loved that game. I wish I could go back in time and play it again for the first time, not knowing what the answers were, and really revisit that world. It's a shame I can't do that.' And in the back rooms of Cyan, as we're designing, we're like, 'Oh, no, I think you're going to get that feeling again.' And that was exciting. And from what we've seen in the comments, it did work that way. And that's really, really satisfying. It's not like we got it perfect, but it was really fun to see the comments of people saying, 'No, I could play it again, and I enjoyed it'.

Time Extension: The studio mentioned recently on the Cyan World's Twitter account how 99% (or roughly thereabouts) of the original game's assets had been lost to time. I'm wondering, what did you actually have to hand while working on the project? I know the Video Game History Foundation helped you to recover some stuff. And I think a few other people did too.

Rand Miller: That's a good question. It was a cafeteria plan — I think is a good way to describe it. We just picked and chose little pieces from various places where people helped. Everything from a computer history museum providing assets off of our original videotapes to one of the original sound guys, Tim Larkin, saying, 'Hey, I think I've got some files that I built the original sounds with', to fans even doing some upscaling of certain things and textures they were able to extract or even the SGI files that we couldn't get into. And then, frankly, going back even to the original game and trying to say, 'Okay, well, I think we can get this sound out of the game to keep it fresh', or going back and getting Gehn's performance. We didn't want to mess with John Keston's performance [writer's note: Keston passed away in 2022 from complications from COVID], so trying to get the cleanest performance of that.

And then there were little tiny pockets of things. I know I found a few textures in my computer in folders. One of the lamp textures I found in there, and I think a few of us around the office had various little textures, pieces, and parts. It wasn't a lot, but it was nice to be able to have actual aspects of the real game interspersed with the things that we, you know, remade as accurately as possible.

Time Extension: Yeah, that's one of the big things that's interesting about this. In terms of voice performances, how did the team kind of go about matching the new with the old and making it seem like a cohesive thing that was made I guess at roughly the same time, because there's always gonna be that challenge there.

Rand Miller: Yeah the character work was not easy and again, we don't have a giant studio with a huge blue screen or motion capture cameras everywhere. It was a scrappy effort, but we spent some money on getting performance capture suits and facial capture helmets that would actually have cameras in front of people's faces. And then, for the performers that were actually mimicking — like for example, Gehn, we had Gehn's performance playing in the background in the basement at our offices and the performer had memorized the lines and spoke along with those.

So we were capturing his facial and mouth movements as he's performing, but not because we're getting his voice. We're doing it just to get those subtleties. And he's doing it as he's walking around. We didn't do it separately. We tried to get both at the same time so it felt more natural. So he's looking at the player and he's speaking those words. And there was something about trying to capture that flow at the same time. And I think a lot of it worked. You know, the process still was interesting. We learned some things as we were going through it, and I think we have further tuning we can do with those characters, but the capture gave us a lot of data to work with, and I think kept the motion of some of those original performances.

Time Extension: We've mentioned about the size of the team and how it's not a big studio. Can we put a specific number to how big the team was when this project started and kind of how it's scaled up during development? Because it'd be interesting to hear what you had to do as a studio to build a team capable of bringing Riven back.

Rand Miller: When we started the design discussions, and even some of the early modeling, it was literally two artists working on it, building the entire world in grayscale and some of the textures as well. Because the few other artists we had were finishing up Firmament at the time. We couldn't spare the resources.

So we did decide that we wanted to grayscale the whole world as much as possible. We wanted to build this thing in grayboxing. We grayboxed the whole world so we could play through it and we could walk through it. And that's a weird thing to do for Riven. It feels like it might be weird because so much of it relies on the textures and the reveals. But I think what we were most trying to accomplish is the sense of scale. Like, 'Are we getting this right?' Because the OG Riven, they didn't have to worry about that. They built the world, and then when you go into a room, it doesn't have to match inside and outside. You know, we could play with that. But this one, we had to match all those things.

So we wanted to know where the problems would be. So having those original artists do that was very useful. As soon as Firmament was over, we began to ramp up the art and programming and pull people over. And then we hired a couple more artists as we went, a couple more contractors. I think by the end we were up to you know probably 15 artists that had been that had worked on it to various degrees. Not all of them were current or working on it at the same time, but by the end, it was probably a total of 15 artists.

And then probably — boy I'm trying to think off the top of my head — there were a few programmers, technical engineers. That probably hit 10 people maybe that were working on that side as well. I think overall, if you count everybody, including overhead and managers and all those things, there were about 30 people that were involved over the course of the four years of making it, which is crazy. I look at that now and think, how in the world did we pull that off? And a month ago, I was not sure we were going to pull it off. There's a lot that happens in that last month and boy it was a crazy ride.

Time Extension: Yeah, it'd be interesting for us to ask you about that. How much can you share about that in terms of where the game was like a month ahead of release? That's a mystery to a lot of people who play video games. There's that feeling with a lot of people who make games where it's like you know 'It's terrible, it's terrible, it's terrible, it's terrible, it's shipped, and it's good'. What kind of work was being done in that last month was it just kind of like testing and getting a lot of feedback from testers on things or was there anything more complicated than that?

Rand Miller: We had tested months previous. Because we had done the grayboxing early on, we could bring testers in early as we were getting places completed — even if some parts were grayboxed — and still get their feedback on stuff. So that stuff was good in getting lists of things that needed to be fixed. The problem was we had giant lists of things that needed to be fixed and just not a giant team.

You look at it a month before shipping and you go, 'There's just no way. There's no way this is going to be finished enough where people appreciate it.' And that final month is special because everyone is focused on polishing and cleanup. There's no more finding bugs. It's just fixing things. So, boy, it really starts to ramp up.

So every member of the team is just going through the bug list. Of course, the emphasis is on blockers that won't let you play through the game, but there were so many enhanced things that were part of the design. And then making decisions like, 'Okay, we're just not going to be able to put that in. It would be great, but there's just no way that that'll make it.' And trying to triage some of those decisions. And then, in the last month, you look at it a month before shipping and you go, 'There's just no way. There's no way this is going to be finished enough where people appreciate it.' And that final month is special because everyone is focused on polishing and cleanup. There's no more finding bugs. It's just fixing things. So, boy, it really starts to ramp up. You know, it really starts to take off at the end. It's an amazing process.

To your point, I wish more people on the outside of this process could see how it works because there's a certain level of controlled chaos and insanity that goes on in that last month that is amazing. I wish we could publish even Slack threads, of what was said and what was done, and 'Oh my gosh, does anybody know why these guys look like this?' or 'Atrus's eyes are sticking out of his head? What is going on?' Or 'There's these weird vertex things shooting off into space?' And you're thinking, 'How are we going to ever get this done?' And then in the final week, in the final days, you start to go, 'I think we'll make it. I think this is going to make it. There's a couple of other things. I wonder if we'll get to them.' And we do. And it's not that it's done, but it's to a point where it's like, 'Okay, I think the public will enjoy it, and we can let go, we can start working on the patches, and move on.' It's crazy, crazy, crazy, in case I didn't make that clear.

Time Extension: In terms of some of the big changes with the remake, obviously you've swapped out live-action actors for CG models, but you've also made it so that the player can move about freely now. It's not like these carefully curated glimpses of the world like in the original. How did that shift impact the design of the environments?

Rand Miller: There's a lot to unpack in that question. The moving around freely is what impacted the way we had to do the characters. As much as we were able to design Obduction with full motion video live-action camera characters, it's because we did it from scratch. You're looking through kind of windows and seeing people on screens and so we were like, 'Oh, we can do that.' But in Riven, people were gonna be able to walk around characters, and characters were going to walk around people. And we knew we couldn't do that with live-action. We've got to do true 3D characters. We also knew that we're small and scrappy and the tools are just starting to get better and better for 3D characters. And it felt like that part of the game, we would do as well as we could, knowing that the tools would continue to evolve.

I think giant studios can spend time and money honing that themselves. We wanted to make sure the environment was absolutely amazing for people. I mean, we wanted the characters to be good, too, but we realized that there were limitations to what we could pull off.

Now, with all that said, let me go back to the free movement aspect of this because you're right. In the OG, we could curate every shot. We could pick the exact angle. We could line up exactly what we wanted you to see. And there was an artistic aspect to every shot that was taken. But, if I switch to the fan side of my brain, what I found is that instead of Cyan and the artists deciding what the players see, the player becomes kind of the artist.

I love that that's shifted a bit into allowing the player to find those really evocative shots that weren't possible in the original, or places that maybe no one has even been to before. It feels kind of special that I may be the first one taking this photo in Riven

I found that as I walked around the world, as I roam around, I find myself looking at certain aspects. You know, the photographer in me says, 'Oh my gosh, look at this. This is a great shot. I'm going to look a little bit more to the right. Oh, that is so cool. I'm taking a picture of that.' Not for gameplay reasons, just because it looks good. And I love that that's shifted a bit into allowing the player to find those really evocative shots that weren't possible in the original, or places that maybe no one has even been to before. It feels kind of special that I may be the first one taking this photo in Riven.

Now, the practical side of it is we had to change a few things. We have to make sure that the player sees certain things that in the OG we could point out very clearly. They may not be looking the way we want to, so can we get their attention with a sound or with a certain movement in a certain way? Or can we enhance how something looks so we make sure that they're given the right view in this direction? And we had to tune those things. We found in playtesting that they didn't look, they didn't see that thing. So it was like 'Okay, let's add another thing. They still didn't see it. Okay, let's add one more thing, we'll silhouette it or attach some cables to it or some ropes to it.' So that had to be tuned in a very different way than the OG.

Time Extension: You probably won't be able to give a specific answer to this, but something that a lot of people are wondering about is the future of the studio and future projects. Do you see yourself approaching more of your back catalog in this way? Or are you more interested in exploring new ideas with the techniques and things that you've learned from Riven?

Rand Miller: I mean, look, it's not a secret that I'm getting a little older. I've been doing these games for a long time and we have a lot of fresh new people at Cyan and it's invigorating. They bring new ideas about how they would approach this and it's exciting for me because I get to look at it a little bit more from the outside. I mean, Riven, I have been very intimately involved with, but I don't feel like I need to be as we move forward.

With all that said, I think the thing that's most exciting to the people who are at the company right now is a mix of things. The whole universe of Myst is huge. There's a lot of really interesting stories and places to be mined. Much of it doesn't require any knowledge of the original Myst, or the threat of Myst, and there's plenty to be done there without necessarily rehashing the other games that are in the quiver.

So I think the thing that's most motivating right now to the company is what's a different window that would look into this world and how could it change and be really interesting to a new audience. That's vague and not vague. What does that look like? What does that mean? And does gameplay stay the same as Cyan has always done it? Or do we make it different? Do we change up even the gameplay so a newer, younger audience would enjoy it as well?