Sometimes the most innocuous of threads will lead you down a rabbit hole of investigation. This initially started as a chat with Adrian Jackson-Jones regarding his work on The Hunt for Red October on SNES, a colourful and surprisingly fun shmup that riffs on the Defender formula (its only real flaw is being a bit too difficult). As part of the research, we peruse his LinkedIn profile, which states that between 1992 and 1993 he worked at RSP, aka Riedel Software Productions, and "designed and implemented the game engine for the CD-i system game Donkey Kong."

This immediately catches our attention, since, as long-time readers know, this author has a mild obsession with both Philips CD-i and the Philips / Nintendo licenses, especially after being the only person to interview Dale DeSharone before he sadly passed away in 2008.

As DeSharone explained at the time:

Somehow, Philips got a deal with Nintendo to license five characters. As I understood the arrangement it wasn't a license of five games but five characters. A number of developers pitched AIM with ideas. I think AIM chose to go with the biggest names that Nintendo had at the time. We pitched separate ideas for a game starring Link and a separate one with Zelda. The development budgets were not high. As I recall they were perhaps around $600,000 each. We made a pitch that we could maximize the quality of the games by combining the funding to develop only one game engine that would be used by both games.

The games which saw release from this deal were: Hotel Mario, Link: Faces of Evil, Zelda: Wand of Gamelon, and Zelda's Adventure. In addition, were two games which went unreleased. Super Mario's Wacky Worlds was an attempt to recreate Super Mario World; the Blackmoon Project website has interviews with Silas Warner, John Brooks, Marty Foulger, and Nina Stanley regarding the game, and a very rough prototype was leaked to the public.

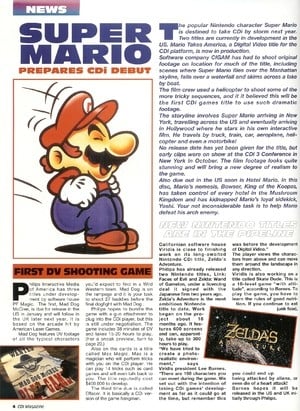

It's not really "playable" in its leaked state, but it had some cool ideas, like common Mario enemies dressed for different time periods. It's a real shame it was never finished, because we love the idea of traversing Greek-themed levels while jumping on turtles dressed in togas! The other was Mario Takes America. There's very little documented information on this, but according to CD-i Magazine, footage was shown to the press, and had "scenes where Super Mario flies over the Manhattan skyline, falls over a waterfall and skims across a lake by boat". No screenshots have leaked, but apparently, the developers shot video footage from a helicopter, making this a fascinating prospect.

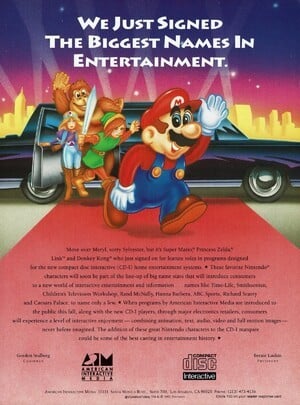

This selection of titles matches DeSharone's description, with popular characters starring in their own games. If we assume Mario, Link, and Zelda constitute three of the five, that still leaves two others – assuming DeSharone's recollections were accurate of course. It would seem the Donkey Kong character was another. Heavy searching brings up very little, with the only site giving it any serious coverage being LostMediaWiki. They do a nice collating available information, including a print advert for CD-i that shows DK, alongside Mario, Link, and Zelda (we like to fantasise that Samus Aran is inside the limo, just out of view). They also provide scans from EGM's gossip column Quatermann, in issues #31 (Feb 92) and #47 (June 93). As with most Quatermann columns, the information is vague. LostMediaWiki also cites Jackson-Jones' LinkedIn profile, but doesn't go as far as trying to interview him. We also trawled our archives of CD-i Magazine and, while the two unreleased Mario games were promoted at various trade shows, we can't seem to find any mention of Donkey Kong.

Another tangential link to this saga is that Stephen Radosh, who was producer on the Mario and Zelda titles for CD-i, was at one time employed at Sega and worked on an unreleased Donkey Kong arcade game while there. As Radosh had explained to Game Informer: "Somehow Sega had gotten the rights to Donkey Kong. You were dodging cars that were pulling in and out of the lot, and you had to get X number of cars parked in spaces." Sadly, despite a golden opportunity, Game Informer didn't pursue this line of questioning further. Given that Radosh was producer on all the released Nintendo-licensed games, and dealt with Nintendo for approval, it seems likely he would have had knowledge of the unreleased Donkey Kong game for CD-i (meaning he would have twice dealt with the series).

The fact we've now stumbled across two unreleased Donkey Kong games is muddying the waters, so let's recap the character's early appearances. Donkey Kong (1981) first showed up in the eponymous arcade game, which is well known. Nintendo's Sky Skipper for arcades also featured gorillas and, while not actually related to Donkey Kong, still kinda reminds us of him. There was an official sequel the following year, Donkey Kong Jr., featuring his son and Mario as the villain. Both this and the original would be ported to the Famicom / NES, and the latter would receive an edutainment spin-off for the home system.

Donkey Kong 3 hit arcades in 1983 and saw a home port soon after. Next was an unreleased game for the NES titled Return of Donkey Kong; LostMediaWiki has our backs again, providing the only known evidence, with scans from Official Nintendo Player's Guide and the Nintendo Fun Club. The IP went dormant until DK's son appeared in Super Mario Kart for SNES in 1992, and then in 1994, there was the phenomenal Donkey Kong '94 for Game Boy, featuring Super Game Boy support and reinventing the original arcade game into what would eventually become the Mario vs. Donkey Kong series. That same year also saw the release of Donkey Kong Country on SNES, by Rare, officially heralding the giant ape's return and vertical ascent in popularity.

We've ignored Game & Watch titles and cartoon spin-offs just for the sake of simplicity. But we're also up to three unreleased games! Thankfully, now that we're speaking with Jackson-Jones, we can lay this entire mystery bare and document the CD-i title for the world, straight from the man who programmed it. Based on his LinkedIn information, his version would have been somewhere from around the time of Super Mario Kart but before the GB or SNES releases in 1994. We ask if he really did work on a version of Donkey Kong for the CD-i, and explain our desire to cover everything possible.

"Ha, yes, that was a very long time ago," he confirms. "The title was never published. You are going to hate to hear this, but I have a memory disorder. I honestly don't remember very much outside of the technology."

Our hearts sink a little, but the technology seems like a good starting point to gather some details. We refer back to our old interview with DeSharone, where he described the CD-i technology:

Philips chose to stay with the original 1987 specification using the original 68000 chip found in the first Macintosh computers. It was dreadfully slow and severely limited what was possible. There was no hardware sprite technology so all movement of characters required the pushing of pixel data by that 68000 chip. There was some hardware scrolling capability but the video memory was very small. If you look at the scrolling in Laser Lords, Alice In Wonderland, Mutant Rampage, Link or Zelda you'll see that you can only scroll about 2 or 2.5 screens horizontally. It was just obviously not a game system and Philips was actually very clear in telling us that they didn't believe the market for this device was games.

"The CDi did not have the kind of graphics or gameplay hardware that we had become used to on other platforms," agrees Jackson-Jones. "Our solution was to actually hold only one screen of data in memory at a time. And scroll things in by a player's movement. So it was an 'infinite' scroller."

This description conjures images of the original Super Mario Bros., where the screen could be continuously scrolled forward until a level's end. This is just speculation, though. So we ask if there is anything else, anything at all, that he can possibly dredge up. Any sort of description of how the game functioned. Did he perhaps have any materials left from the project in an old box somewhere? Unfortunately, he responds: "No, my memory is so terrible I don't even know where I worked on it."

Given that Adrian Jackson-Jones suffers from this condition, and wishing to respect his privacy, we want to be absolutely certain he consents to our publishing such information. We reiterate our intentions and, while he can't recall any specific details of the game, he's certainly amicable to sharing what we've discussed. "You can put anything anywhere," he assures us. "I am happy just to be asked. I gotta go, but thank you."

Although we've not ascertained how the game would have played, we at least have confirmation of its existence, an approximate date, the company handling it, and several leads on who else to ask. We trawl the credits of all the games Jackson-Jones worked on, and find a recurring name: Kevin Gee. Both gentlemen also worked on the unreleased Steven Seagal is the Final Option game while at RSP, so perhaps Gee had worked on or at least seen Donkey Kong. He replies: "Unfortunately, I didn't get to work on this title. And yes, there are many titles that never see the light of day."

Undeterred, we next pursue finding the company owner himself, Michael J. Riedel. It takes a while, but eventually, we get a reply from Riedel:

That was a long time ago and I don't have much to say about it. I have been thinking about it, still not sure I understand why there's any interest in a cancelled project that never saw the light of day. And I don't think there's much I can add to that, this is now decades ago and it wasn't particularly memorable in the scheme of things.

At last, we've found the man behind the entire enterprise; we just need to convince him. Both this article's author and site co-founder Damien McFerran send impassioned pleas. We explain how this project is part of the history of the CD-ROM medium itself, intertwined with that of Sony, Philips, and Nintendo. Donkey Kong is now an enormous IP, and so there is value in understanding its history. Readers love articles on unreleased games because they allow us to live vicariously and imagine: what if? This is an exciting mystery and he might be the only person who can help us decipher it. We finish by referencing Indiana Jones, and how knowledge needs to be preserved.

Our combined explanations work.

Riedel replies:

You motivated me to check if I had any old data or manuals pertaining to this project, but unfortunately I found nothing. Your email also started getting the gears turning again and I remembered having a project in the works with Sony that never came to fruition because of what happened with Nintendo. You're really taking me way back. I'd be happy to talk but can't promise I'll remember anything interesting. If you can bring background info that might help. Late afternoons or evenings work better for me, I'm in the MST time zone. What works for you?

Riedel being on Mountain Standard Time would mean the interview would need to take place around 2am British Standard Time. But it would be worth it. We carefully curate and send information: DeSharone excerpts, the interview with Radosh, magazine scans related to the other Nintendo games, plus links to Blackmoon Project articles, and a list of topics we can cover. We're especially interested in this mysterious Sony project he mentions.

"I have to say, reading all this has confirmed how little I remember about the Donkey Kong project," he replies after going through the sent material. "Same for the Sony project; I don't even recall if it was for the Nintendo PlayStation or the Sony hardware that came after it. RSP was a work-for-hire company and cancelled projects were not uncommon. Once it was over, everything was tossed out, apparently including my memories of it. While I'm sympathetic to your cause and was really hoping that reading this stuff would spur some memories, I just don't have anything to add."

Though disappointed, we thank him for his time, describe the article which will be written, and ask that should he recall anything at all – no matter how superfluous – to please contact us so we can update said article.

While it didn't culminate with Time Extension revealing the world's first footage of the game in action, the journey proved fascinating and brought together a lot of eclectic information. It also reminds us how important it is to document knowledge before it's forgotten. Somewhere out there will be others who saw this game, maybe worked on it, we just need to find them. Along the way, as with Super Mario's Wacky Worlds, we may even find the game itself. Until then, the speculative possibilities of what it could have been are limited only by our imaginations.

John Szczepaniak is the author of The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers trilogy, which has recently had a fifth offshoot volume released. He keeps saying he's getting out of writing, but just when he thinks he's out, they pull him back in.