Given the recent furore over Jeff Grubb's comments on 1980s European gaming being "merely a scene" and the resultant backlash, it seemed prudent to me to take a broader view.

Grubb's comments on the European home computer "scene" got a few people's backs up (mainly Europeans, as you can imagine), but sadly, this isn't a new phenomenon—it's been happening for decades.

Esteemed writer Arnie Katz, speaking in the December 1990 issue of Video Game & Computer Entertainment (page 196) and then doubling down in the January 1991 issue (from page 114), makes thinly veiled attacks against Europe and Japan, stating:

Software quality is a growing concern. The game design gap between Japan and America is no illusion. No Japanese development house has its finger on the US gaming pulse. Japan's culture is more alien to ours than Britain's. No American design house would attempt to invade the Japanese software market but it hasn't stopped Japan trying the opposite. Gamers in this country are coming to see Japanese games as repetitive, unimaginative, and formulaic. Japanese designers are also not adept at creating new game genres and formats. The only solution is to limit overseas designs and increase investment in US development.

I implore you to read both those columns in full, it's a wild xenophobic ride! Keep in mind Katz is seen as a pioneer of games journalism and was a "writer, editor, lecturer, and game designer", and yet promoted such outlandish views. Though to be fair, such views were more common in 1991. More recently, Sean Kelly, director of America's National Videogame Museum, expressed displeasure at the mere existence of games archives in Europe, stating:

I just feel like 'the' videogame archive belongs in the USA. Videogames were born here and their ultimate historical archive should also be here. It would be like re-locating the first McDonald’s to Japan or the ABBA museum to the USA. They just don’t belong.

So while Grubb's stance is regrettable, his attitude is just part of a greater endemic problem that goes back decades: American writers, historians, archivists, YouTubers, et al, tend to have a highly myopic US-centric view—not just of Europe but the whole world, especially Japan.

This is strange given that the "NES era", which Americans are obsessed with, is itself an offshoot of Japanese games history. Does this make America a "mere footnote" to the foundational Japanese market? No, of course not, that would be nonsense. To understand game history, we need to look at it holistically, especially the subtle interplay between all regions (it's worth noting, too, that everyone is guilty of this to some degree; how many British gamers, for example, are aware of video game history in France, Spain, Germany, South Africa, Hong Kong or Brazil? We all do it!).

Let's focus on Japan for the moment: a nation which has done much to shape the video game landscape of today. American pundits have misunderstood, sidelined, or outright ignored important historical events. Below I've noted some examples of this which eventually lead to Japan's views on Europe during the 1980s, thus circling back to disprove any gaslighting over Europe's importance. It is written in solidarity so we may all seek enlightenment together.

When I briefly lived in Japan to conduct interviews, it was with the intention of filling gaps in our collective knowledge. The resulting body of work led some colleagues to describe me as the leading English language expert on Japan, which is flattering, but not quite accurate. The knowledge gained only revealed how little was documented and how much more research was needed while reframing much of what was known about Japan.

For starters, almost nobody paid any attention to Japanese computers, despite a long list of prominent companies either starting out on computers or being heavily invested: Enix, Square, Koei, BPS, Game Arts, Falcom, Hudson, T&E Soft, TecnoSoft, and even Konami, to name a fraction. Some writers may have paid lip service to Dragon Quest creator Yuji Horii playing Wizardry, but who dug into his erotic adventures prior to this? Come to think of it, did anyone research Japan's complex and influential history of erotic games?

While America had Apple and IBM compatibles, and Europe had the C64, ZX Spectrum, and Amstrad, Japan had its own highly influential PC eco-system. There are two research papers on this, by David Methé, and also Joel West (PDF download), which together give a fantastic overview, including how NEC for a time held an 80% market share.

The Nintendo Problem

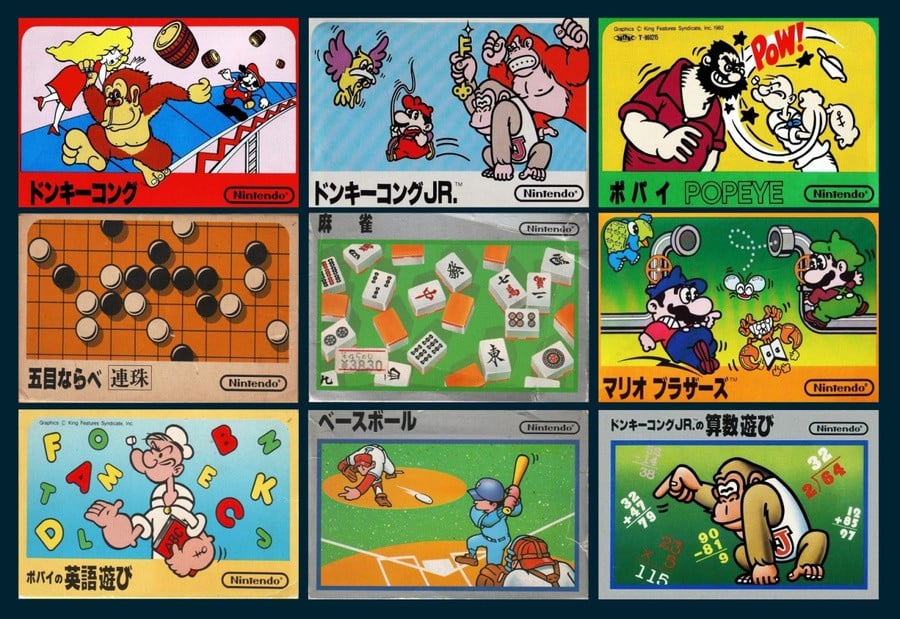

Once you have a grasp of Japan's poorly documented computer market, it helps reframe the Nintendo bias which is so prevalent. American coverage of Nintendo's 8-bit hardware promotes it as an immediate, universal, unstoppable success—this is because they interpret events through the experience of their domestic lens, where it launched in 1985, more than two years after Japan and with Super Mario Bros. from the outset.

The truth is the system had a very rocky start when it first emerged. The MSX computer range had a bigger market share and was treated as more important. Its launch line-up and catalogue for 1983 were beyond abysmal. Masaaki Kukino did not want to work at Nintendo because it didn't look interesting, choosing Konami instead. Nintendo sought the greater experience of Hudson, with Takashi Takebe stating that Nintendo didn't know what it was doing back then.

Meanwhile, Sega's 8-bit competition, the SG-1000, is often dismissed as an outright failure despite having a stronger launch. There's a common perception that the Famicom offered a more technically advanced experience and had superior screen scrolling capabilities, yet, for the first 12 months of release, it didn't have a single game which featured scrolling.

You will have seen similar coverage countless times—because the NES was the formative experience for many Americans, and because Nintendo gripped the nation for so long, it skews analysis and research of various eras.

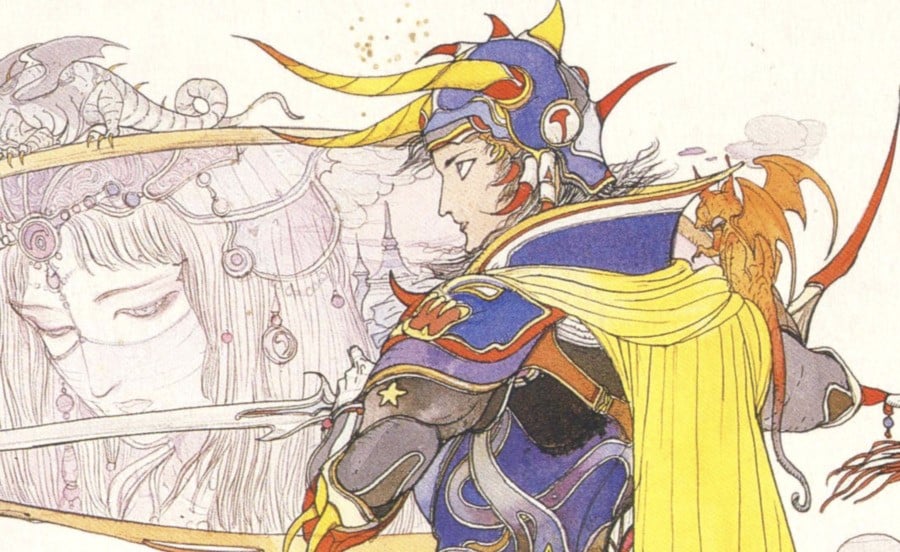

The Final Fantasy / Dragon Quest Problem

American coverage of Japanese RPGs, with a few exceptions, tends not to go further back than Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, despite a fascinating heritage predating these two. Both Square and Enix published a variety of earlier RPGs on computers. In fact, Enix didn't even develop Dragon Quest; it was only the publisher, yet it's repeatedly and erroneously attributed full responsibility. The actual developer was Chunsoft. Perhaps this near complete disregard for early JPRGs is down to the language barrier, but it permeates so much of public discourse.

Even the esteemed writer Matt Barton, in the fabulously comprehensive Dungeons & Desktops book, which examines the history of computer RPGs, muddles the Japanese side. He begins his examination of Japanese RPGs only with The Legend of Zelda, Dragon Quest, and Final Fantasy, mistakenly stating Dragon Quest began on the MSX before being ported to the NES (it's the other way around).

In fairness to Barton, he does at least explicitly state:

Millions more gamers have played The Legend of Zelda and Final Fantasy than any of the American-made games in this book. I’ll leave it for other historians to explore how these games affected the Japanese industry.

This is a fair admission, but it's still frustrating knowing how rich JRPGs are and how many more examples have reached the US. No mention of Falcom? Koei? Game Arts? At least he covers Sega's Phantasy Star. Plus, there's the even greater number from Japan which predate and influenced the obvious examples.

Surely, if these Japanese-made games were played by "millions more" than the American-made games, it behoves us to understand what led to them? This is not an attempt to diminish the importance of America, the way Grubb diminished Europe, since when you actually dig into the early history, you find that Japan took influence from both America and Europe. In fact, Dragon Quest programmer Kouichi Nakamura, in the book Family Computer 1983-1994, states he based the menu system on that of America's Apple Macintosh. We are all interconnected.

The Hydlide Problem

Discussion of RPGs leads to Hydlide, and the fact the American-lead narrative around it always frames the game as competing with The Legend of Zelda and of being worthless garbage. You've probably seen the AVGN video on it.

Except Hydlide came out in 1984 on Japanese computers, whereas Zelda came out 1986 on the Famicom Disk System. Zelda saw an American release 18 months later in 1987, with Hydlide following in 1989. You can't criticise a game for being weaker than something released after it, especially in the context of it being five years removed from its original launch. AVGN at least gives the original date for Hydlide, but even so, the criticism is unwarranted, and it spawns countless hateful imitators which, due to sheer volume, poison the history. Interestingly, the American response at the time was more objective, with EGM issue #2 describing it as a "good alternative to Zelda". It shows how modern critics exist in a social media echo chamber which magnifies increasingly hyperbolic rhetoric.

In Japan Hydlide was a multi-million seller—which was significant for 1984. It sold a million copies across at least eight computer formats, and later a million on Famicom alone; thus, it also represents a historical turning point where the Famicom reached critical mass, encouraging other developers to abandon computers in favour of it. Hydlide also received an award plaque from Toshiba EMI commemorating its sales. Moreover, Hideo Kojima has publicly tweeted that Hydlide on computers influenced him when creating the Metal Gear Solid series; Hydlide's freedom shocked him, and he wanted to recreate that feeling. It's also one of the first games ever to feature recharging health, alongside the American-developed Polar Rescue, and it influenced Falcom's long-running Ancient Ys series of RPGs.

Not bad for a game so hated by America.

The Tower of Druaga Problem

When asked about the influences on Hydlide, its creator Tokihiro Naito cited Namco's The Tower of Druaga, which is even less understood. Also released in 1984, Druaga is one of Japan's most important games—its DNA can be found in seemingly everything, from Zelda to the Soulsborne series. However, it didn't leave Japan until Namco Museum Volume 3 in 1997, and in the ensuing decades, seemingly not one Western critic has tried to understand it.

IGN Staff in March 1997 scored the Namco compilation (all games) 6/10, stating: "I could go on and on about how bad Druaga is but that would only seem to give it some sort of undue merit." The standalone IGN review from 2009 scored it 3/10 stating it's: "Little more than pointless. I don't get it, and neither did most Americans in the '80s. Japan likes it, though." Except it was never officially brought over to American arcades in the 1980s, and there was no attempt to understand why Japan likes it. Jeff Gerstmann of Gamespot scored the compilation 5.6/10 in May 2000. And to show we're not just picking on Americans, Eurogamer scored Druaga 4/10 in 2009. You can find newer reviews, too—most reviewers are baffled by it.

Now, there's nothing wrong with giving a low score and warning potential buyers about spending their money. This is fine. But not one critic shows any comprehension of the game's background; which in turn highlights the difficulty of even "correctly" playing it today. Druaga was popular in Japan because every floor featured an obtuse riddle to solve, and players would share hints and tips in their arcade's notebook - itself a unique cultural artefact that few outside Japan discuss.

Now, if you're thinking that an armoured knight in a super difficult game where players share messages sounds familiar, say a bit like the Soulsborne series, you'd be correct! From Software director Yui Tanimura says so explicitly:

When I was a kid I used to go to the arcade to play Tower of Druaga and I’d swap information with other people playing the game. What we have is similar to that, but on a much larger scale. I create parts of the game that players might not understand, so that it becomes a chance for players to interact with each other.

Going back further, Shigeru Miyamoto loved it, stating in 1986:

I'm a big fan of Druaga. We had them bring an arcade cabinet to our office, and I played on it. But I couldn't get past floor 60… I got sent back to floor 14 and couldn't end up finishing it. Still though, the maze programming is excellent, as I've come to expect of Namco. It's impressively well-made.

Once you know this, you can't help but see elements of Druaga in Zelda's dungeons, a game Americans adore.

Now, if you simply don't enjoy playing Druaga, that's fair enough. But given how many Japanese developers admit to loving it and took influence from it to create the games which were popular outside Japan, it's worth trying to understand.

Both Zelda and the Souls games took inspiration, which isn't bad for something Western critics described as "without merit" and "pointless". Lots of important games have aged badly after 40 years, but we should still strive to appreciate them. Knowing its background, and how people played it in 1984, actually makes it more enjoyable. Recapturing that feeling today is difficult, though the fan-translated PC Engine port comes close, providing basic clues to solve the riddles and giving passwords after each level.

Japan's Connection To Europe

While Japan may have been under American occupation since the end of the war, absorbing various facets of culture (Yoshio Kiya of Falcom described buying an Apple II computer from a store catering to US military personnel), it still had a relationship with Britain and Europe. Japanese developers also kept an eye on what Europe's "mere computer scene" was up to.

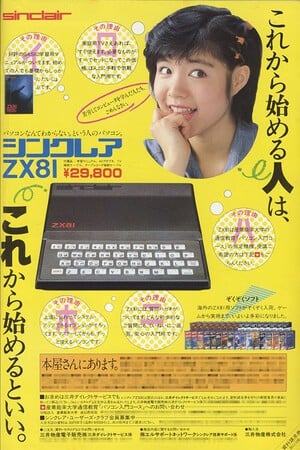

Masakuni Mitsuhashi, a key figure at Game Arts credited on the first two Silpheed games plus Lunar: Eternal Blue, earlier in his career developed MSX maze game Illegus Ep. IV. In an interview, he emphatically stated he took inspiration from the British computer game 3D Monster Maze on the ZX-81:

Now, where did I see it... Through ASCII publishing? Maybe I never played it, but I would have seen computer magazine articles or screenshots. There were many computer games. Japanese magazines had content on software from other countries. ASCII was the one that covered the international scene. Of course they covered hardware from abroad, such as the Apple II, and wrote about them alongside the domestic [Japanese] stuff. So we saw many, many games, from many other countries, from around the world. And so took inspiration when making our own games.

It sounds almost unbelievable, except during the interview, he produced an old Japanese magazine showing international coverage, and even an advertisement for the ZX-81, which was marketed in Japan! Far from being an unimportant "mere scene", European computers and their games were having a direct impact on Japanese creators, as did America.

It's almost as if the entire world were somehow interconnected, with everyone having a subtle influence on everyone else.

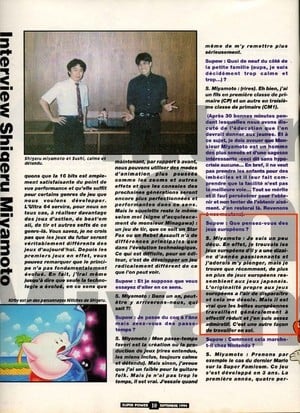

Another example is this quote from Shigeru Miyamoto, where he laments how European games have changed in the 1990s compared to the 1980s, when the ZX Spectrum and C64 were at their height:

I'm a bit disappointed. I used to find the European games of a decade or so ago exciting, and I loved immersing myself in them, but I find that recently, more and more European games resemble Japanese games. The originality of European games seems to be disappearing, and that saddens me. But it's true that European companies generally work on a smaller scale, and I admire that. It's another way of working in itself.

It's taken from the September 1994 issue of French magazine Super Power, on page 10, where they ask Miyamoto what he thinks of European games. Given the date, he would be referring roughly to 1984, when ZX Spectrum titles such as Atic Atac, Sabre Wulf, and Underwurlde were enthralling British kids. Which makes this documentary by Critical Kate especially interesting, since she hypothesises these same computer games directly influenced Nintendo, citing how they were all developed by Rare, back when it was known as Ultimate Play The Game. And, of course, Rare should require no introduction—it was the British developer which defined Nintendo hardware during the 1990s.

How and why might Nintendo have a ZX Spectrum or any other 8-bit micro, though? Well, think back to the earlier anecdote about Nintendo approaching Hudson due its expertise with computers, to create Family BASIC for the Famicom.

Takashi Takebe also revealed:

I remember the ZX Spectrum. The first time I went to London was for a computer convention. I went to help out at the Hudson booth. <laughs> This was probably around 1982? We took out a booth for the convention and tried to find businesses willing to port our games to the computers popular in the UK. Because Japan based its traffic system off of England's, walking around in the city felt quite comfortable. Those sorts of business deals were made on the development side. I remember the company's then president bringing in a ZX Spectrum and ordering us to make games for it. It had a Z80 CPU, so we started by porting over our 'package', similar to modern SDKs, and then the games themselves.

Given the descriptions by both Mitsuhashi and Takebe of following Europe and physically having the ZX Spectrum in Japan, Miyamoto's statement about immersing himself in European games dovetails nicely. Importantly, it also shows how the DNA of Britain or Europe's "mere computer scene" is woven into both Hudson's and Nintendo's history.

Think about this: Hudson's business model was influenced by the British computer market circa 1982, and it went on to achieve tremendous success in Japan. Nintendo then approached them as the more experienced company, relying on Hudson's computer expertise, granting beneficial third-party licensing, even allowing them to create Mario games for computers. Later Hudson teamed up with NEC, a company with an 80% monopoly on domestic computers, to produce the PC Engine console, which took Japan by storm.

Based on Grubb's obsession over sales figures, he and other Americans might dismiss the PC Engine given that its American counterpart, the Turbografx-16, sold poorly. Which exemplifies this entire debate—it's irrelevant what Americans feel. In Japan, the PC Engine held second place in the 16-bit console market, above Sega's Mega Drive, and it prompted Hiroshi Yamauchi to push ahead with the Super Famicom (see also Game Over). Does this mean Sega was "merely a scene" in Japan? No, that's obviously a ridiculous statement.

This feature paints with a wide brush on multiple topics, but it's not trying to claim Japan or anywhere else is more important. It's about respectfully acknowledging the value and nuanced interplay between markets.

Nor does everyone have this problem. For example, Basement Brothers is one of the best channels on YouTube, using real Japanese computer hardware and contextualising the games covered. Kurt Kalata of Hardcore Gaming 101 has long documented Japan, both in terms of Sega and JRPGs themselves. Chris Covell has also done tremendous work documenting Japan. So, there are great examples of accurate, objective historical understanding.

But game history still has a genuine problem of one particular perspective dictating the narrative; proponents of the "Amerika über alles" doctrine all diminish the voices from other significant spheres of influence and create a warped or untrue portrayal of events. On a smaller scale, British and Japanese gamers often view the world of interactive entertainment through their own narrow lenses.

To bridge this gap, we need to accept that the only true wisdom is in knowing that we know nothing, and thus must research things more—we all, subconsciously or not, tend to gravitate towards our own personal experiences when it comes to making sense of history.

Please, please, if you have any genuine love for games, read widely and try to grasp the context of global events.

John Szczepaniak is the world's leading English language expert on the history of Japanese video games, occasionally lecturing on the subject. He's been a journalist for 20 years and has written for more than 20 publications, including Retro Gamer, GamesTM, Official PSM, Game Developer, and Gamasutra. He is the author of The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers series of books and Japansoft: An Oral History, while contributing to others.