Preserving history is often all about archiving before it is too late, especially when it comes to games. Saving that floppy before it becomes unreadable, ripping that CD before 'bit rot' sets in and a hard drive before it dies a quiet (well, sort of) and untimely death.

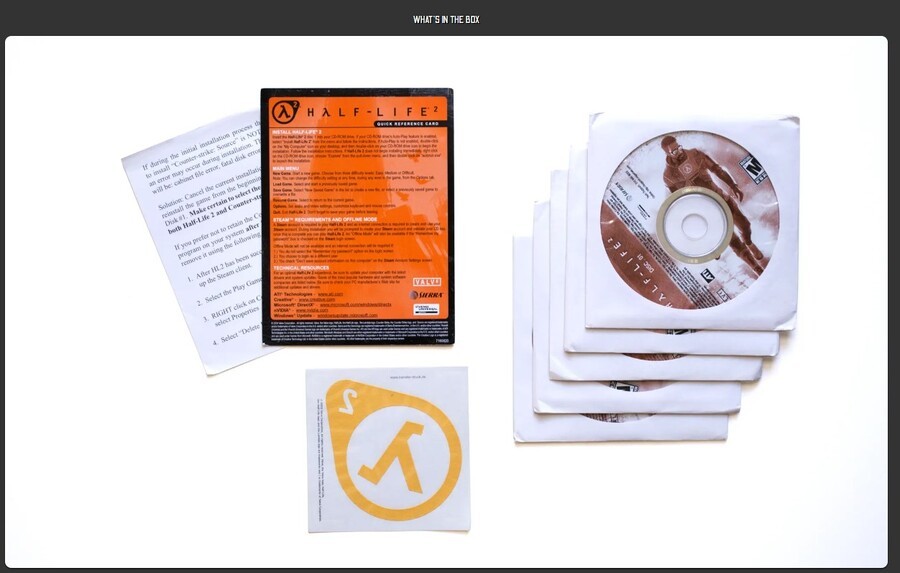

But what about the excitement of bringing home a brand-new game from the shop, looking at the artwork on the ride back, reading the manual and all the extra stuff before even loading the game? How can one preserve a feeling like that? We met the biggest fans of the good ol’ big boxes to discuss their work on making their collections accessible and building a community to share their passion together.

Ernst Krogtoft is the owner of Retro365, a blog devoted to photos of his quite large collection, amongst other things. In every post, Krogtoft discusses the development of the game, showcases the gameplay and features beautiful shots of his collection. The collector recalls that he “wanted to create a place that strived to not only tell the story of the games but also pay my respect to the pioneers who helped create the foundation for what now is the world's biggest entertainment industry.” He mentions attracting around 3,000 visits per month.

It is understandable how not all the posts are so detail-heavy. "Detailed articles can often take months, if not years, of research before I decide that they’re ready to be published," he says. Krogtoft mentions the overall process (research, writing, photography, recording gameplay) taking from 10 to 70 hours of work per post, along with the added difficulty of English not being his first language. “While I occasionally write about popular mainstream titles from the late ‘80s to mid-’90s, my passion lies with the earlier and lesser-known titles. I want to preserve the history of the games, the developers, and the times they represent, even down to the most obscure titles, as all have a part in history."

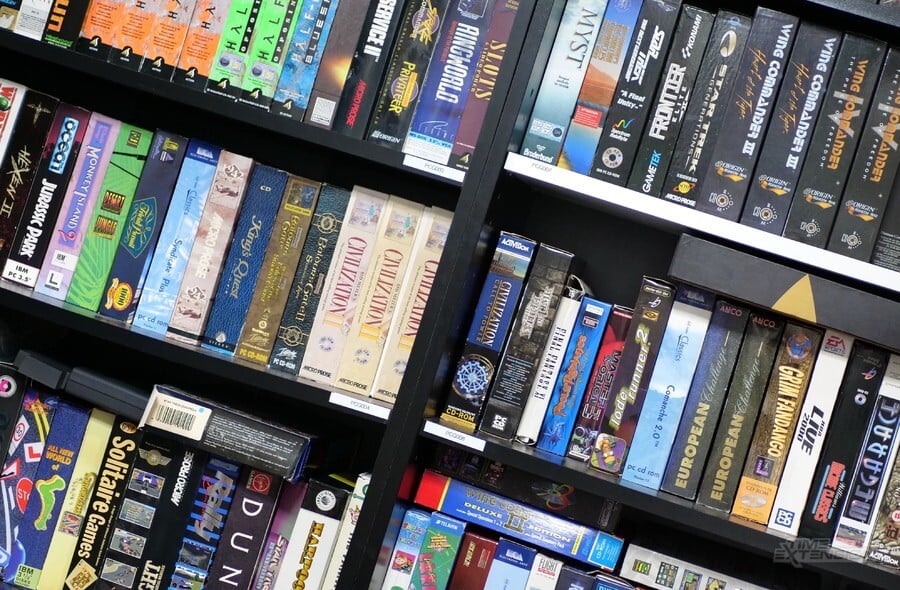

Benjamin Wimmer started collecting big box PC games as a child, as the backbone of his collection is still the old titles acquired in the late '80s. But what brought him to full-on collecting games? “It was around 2015 – I found on Google Plus a physical release of the Commodore 64 version of the endless runner Canabalt. Since these releases, back then, weren’t expensive, I thought, why not take a look through classified ads to find other big box games?” The year after, he started his website Big Box Collection. "Originally, I was sharing my collection on Google Plus, mostly an archive for myself with photos and Excel sheets. Then, I decided to buy a scanner to create HQ versions of the artwork; that was my first objective. I wanted to use videos, but that’d be too much work."

On the big box collection website, it is possible to browse his entire collection scanned in 3D. Visitors can rotate the boxes and see them from all sides, along with the contents and info on the game as well, much like a digital library of big boxes. “I don’t see why other websites couldn’t do that, especially those that specialize in selling old games, like GOG,” he says. Wimmer also hopes that he never has to move apartments again, since the last move took an endless number of boxes for, well, the big boxes. “I think when I started the site in 2016, I had maybe two or three hundred games; now it's more than double that.” But he always follows an unspoken rule: never spend more than 10 Euros for a game, as he says patience brings the greatest rewards. For Wimmer, it’s not about keeping games sealed or reselling them; instead, it’s the fun of the hunt.

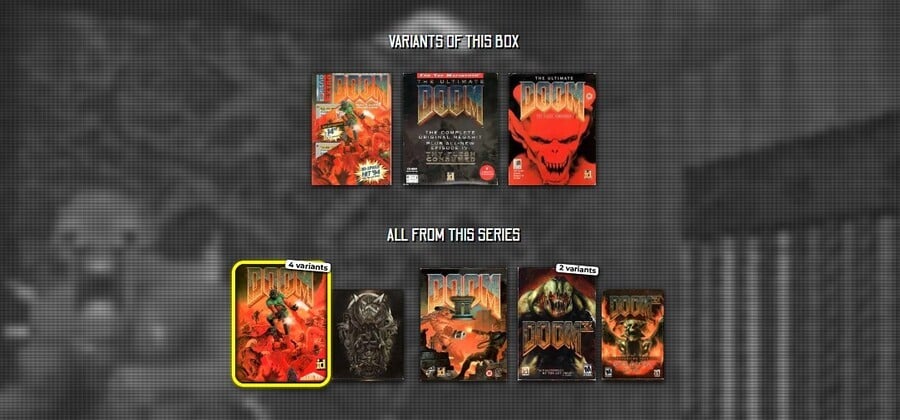

Michel Mohr is working on an app that will allow everyone to digitize their big box collection. He says that while lots of efforts are being made to preserve older games. "Often the packaging is neglected beyond a tiny cover thumbnail," Mohr says. "MobyGames does often have large cover/back photos, but these are presented as flat photos." He also mentions how computer boxes are a Wild West, ages removed from the standardization of console releases of the '80s and '90s, as every game can have different contents and different cover art depending on the country it was released in. “Back in the day, you'd buy Daggerfall and read the box ten times over on the way home. Your imagination was kickstarted by the pictures and text on the box. Booting up an old game from GoG nowadays misses that experience, that context."

The mobile app, currently in beta and available on the Discord server, allows the creation of a 3D model of a game box by simply snapping a picture from each side, defining the corner points and adding information such as title, barcode and size. Users can contribute their titles to the archive, with the database now being around 300 boxes – but Mohr says the long-term goal of the project is to “build a community that can trade, discuss and wishlist games."

Clearly, an archive like that would also need moderation and someone who controls the uploads, as that can be a little more difficult to manage, says Mohr. Finally, the VR app is designed to let users enjoy the boxes like they were holding them in their hands. "I'm currently working on expanding that to let collectors re-create their home 'museum' in mixed reality and share it with others to visit. They can place the boxes where they are in their real space and add voice clips to provide a kind of guided tour and context."

All these private efforts showcase a community which is not simply content with keeping games sealed or, worse, reselling them at high prices. Instead, they would like their collections to be shared with others, thus giving a chance to those who were not around to experience the heyday of big box games. They are working where other companies seem to have failed or simply not care, bringing back the excitement of holding a big box in your hands. Virtually, at least.