Imagine waking up to find you've been sent a mysterious 5.25-inch floppy disk. Where does it come from? It's not a standard disk: there's a series of holes drilled in it, and you realise it's for an obscure, almost forgotten computer from the 1970s, sold only in a specific region of Switzerland. What mysteries does it contain? How was it used? Where does one even acquire a working unit to perform the necessary digital archaeology? It sounds like a wild adventure out of a John Titor movie adaptation, but actually, for Dr Yannick Rochat and Sophie Bémelmans - and their Swiss colleagues - it's just a normal part of daily research.

The pair are part of the elite Confoederatio Ludens squad: about 20 researchers from four Swiss universities, tasked with documenting and studying domestic videogame history, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation to the tune of 3,154,295 Swiss Francs, or about £2.8 million converted. That's a generous volume of funding for a nation-state with a smaller population than London. In the project summary, there is this sentence: "[…] the project is a step to the broader preservation of a highly ephemeral cultural heritage that is currently vanishing". The name CH Ludens is a reference to Switzerland's Latin name, Confoederatio Helvetica.

"This amount is quite uncommon in game studies," admits Rochat. "Pierre-Yves, Sophie, Johan, and I are only one-quarter of that project. The other partners are Zurich University of the Arts, University of Bern, and Bern University of the Arts. The CH Ludens project brings together researchers in game design, history, digital humanities, sociology, communication sciences, mathematics, computer science, and so on."

The recent History of Games 2024 conference gave these researchers an opportunity to share their discoveries. There were no fewer than six talks from Swiss academics, roughly 10% of the overall number! All of them were enthralling, revealing a world little known to outsiders.

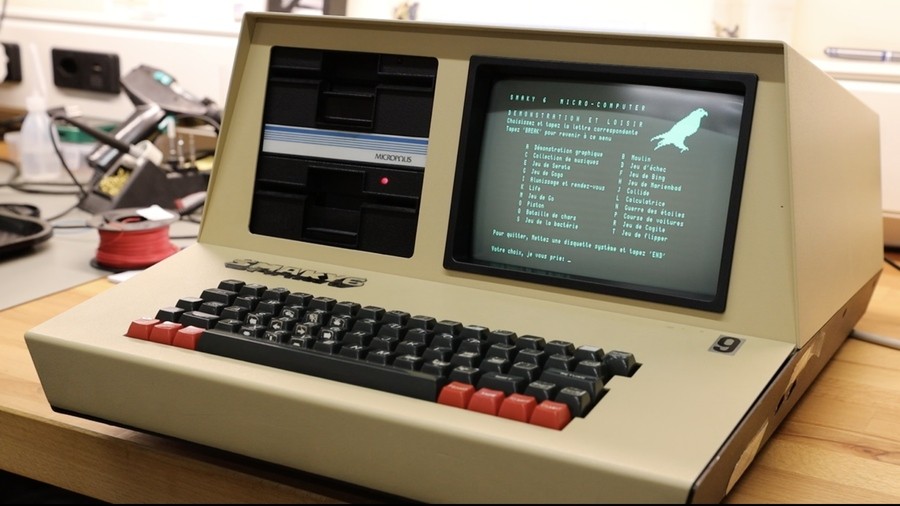

The mysterious disk was for a Smaky 6; it was part of the Smaky range of computers, exclusive to the French-language region of Switzerland, between 1974 and 2000. This specific model launched in 1978 and, surprisingly, has no emulator yet. "Yes, the Smaky 6 does not have an emulator," confirms Bémelmans. "Its microprocessor is a Z80. The Smaky Infini emulator which exists reproduces the Smaky 400, which was a card you put in your PC to get access to the Smaky environment. It can run software written for the microprocessors 680x0, therefore not the Smaky 6, but the ones since Smaky 8."

Rochat and Bémelmans in their talk detailed the challenges of acquiring a working Smaky 6, the convoluted lengths needed to repair it, and then exploring the 20 distinct programs stored on the disk. Software that could only be experienced on original hardware. But what were they?

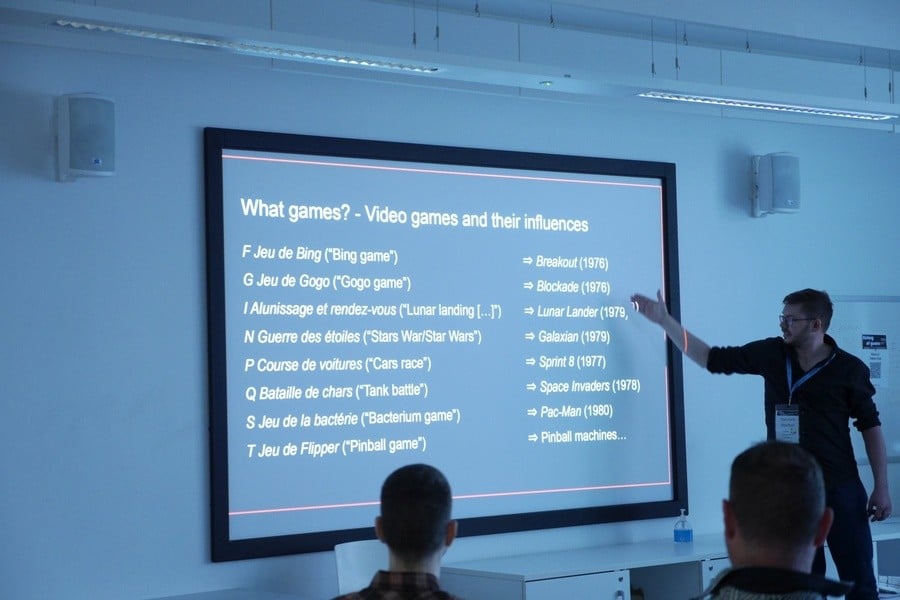

There was one utility, a calculator. Five demos: one for graphics, a "mill" simulation, a music collection, curvature design, and gas modelling (as in atmospheric gas). The remaining 14 programs were games! Six were replications of board games, while eight were traditional video games. This is where the archaeology gets interesting. The team were able to narrow the likely age of the disk based on the fact the games were mostly clones of existing arcade titles from between 1976 to 1980. Now, you might think computer clones of arcade games aren't that interesting, but the Pac-Man clone contained a built-in level editor, which was quite an innovative idea to implement! (Thematically, it was based on the idea of white blood cells eating pathogens and came with a lengthy text backstory.)

The software was precompiled, meaning the source code could not be seen without disassembly. Bémelmans and Pierre-Yves Hurel would meet and interview Daniel Roux, creator of some of these programs, and understand that the floppy disk was most likely a compilation of student work, as suggested by a 1979 documentary shown on Swiss national television. The interview had some amusing moments, since Roux recognised that he created the pinball game, but had no recollection of having played a pinball table prior to that. The disk also gave them an opportunity to network with micro-computer collectors, among others, while developing a better understanding of the local history of Lausanne.

The Smaky 6 is just one tiny aspect of the history of digital games in Switzerland, dating from 1967 through to the present day. If you visit Swiss Games Garden, you'll find over 700 titles listed! These are across a range of formats, including the Amiga, Atari ST, Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum, DOS, and exclusive regional computers, plus consoles.

"The database is still under construction," says Rochat, adding, "We know that tons of games are missing from all the decades. This list started ten years ago because game developers wanted to show that there was a local production. Rapidly, they started adding older games. Scholars joined the project during a hackathon in 2017. The new website Swiss Games Garden was launched more or less two years ago."

Over 700 games, and there's still plenty missing? Incredible. But with so many, what should interested readers look at, if wanting a sample?

"Traps 'n' Treasures on Amiga is famous," suggests Rochat, before giving a detailed list. "The creator, Roman Werner, is a really nice person, who has been documenting his work extensively. Speedy Blupi, aka Speedy Eggbert in the US and many other countries, was available worldwide on game compilations, meaning it has developed a cult following. If you need more, some of my favourites include The Last Eichhof and GLtron. CH Ludens has also produced two articles which might be of interest to your readers: one dedicated to the Swiss publisher Linel, which released a lot of games, and the other to the Necronom game, inspired by the works of Swiss artist H.R. Giger."

Necronom on the Amiga catches our interest, given it's an atmospheric hori-shmup. But it's also worth pointing out Blupi - the character dates back to 1974 in Switzerland (created by Daniel Roux for a comic), and consists of around a dozen eclectic and diverse games, released between 1988 and 2003, featuring the eponymous yellow figure. In many ways, the Blupi series is analogous to the UK's own Dizzy series.

By now, we've hopefully shown you how Switzerland respects and appreciates its video game heritage, making great strides to research, document, and preserve it, with generous funding allocated to do so. We're highlighting this because, in comparison, the UK has been woefully lacking.

As we've shown, the British press doesn't care about academia or its own history. We gave the world the ZX Spectrum, which became astronomically popular, especially across Eastern Europe, and we continue to develop successful games to this day. The History of Games 2024 conference was an opportunity for the press to celebrate these achievements and also the bringing together of delegates from 18 different countries through the shared appreciation of "play". It was a glorious showcase of human and technological potential and collaboration. The lack of press interest was shameful. Whereas in Switzerland, the press actually makes extensive use of academic expertise - this page lists examples where they called upon academia for commentary. The upshot of this is you won't find comically inept statements on Swiss TV since they rely on experts.

As for funding for preservation in the UK, there is almost nothing. In fact, while America has the VGHF, and Japan has the GPS, there is not even an equivalent organisation in the UK. The National Videogame Museum in Sheffield is nice, but its modus operandi is different; it's more for public attendance and, like other museums, has found the last few years very challenging. Why? Why do the powers that be not care?

This led to a very long and very complicated conversation at the conference, regarding government tax relief for British developers, and how Rockstar North had manipulated the system to take £42 million of the available relief, despite being one of the biggest and richest developers globally.

As for the Swiss granting £2.8 million purely for history, Dr Nick Webber, director of the Birmingham Centre for Media and Cultural Research, weighed in: "Nothing at all stopping us from doing something similar in the UK; we just need people to come together, build a consortium, and want to do it. The Swiss team brings together a critical mass of experts across four universities, with the expertise and vision to deliver the project. For a cross-cutting project that looks at both arts and sciences, it's possible to attract millions in research funding. Not saying this money is straightforward to get - bringing a consortium together takes a lot of effort and focused work. Your application goes into a competitive pot where around 80% of applications are rejected, because there are too many good ideas and not enough money. But there is money there if we have the will to chase it. The Swiss team had the will."

We chatted further with Rochat and Bémelmans who were forthcoming with details, including that the success rate for that kind of interdisciplinary application in Switzerland was only 27%. They also spoke about the urgency of things, given the age of first-generation developers. As the two revealed: "We were amazed it was accepted on the first try. Research projects often have to be submitted a second time; they would be improved in the process by taking into account the many reports written by anonymous reviewers - five in our case. We have to thank the reviewers, who were enthusiastic for our project, and the scientific committee, who followed the opinions of the reviewers."

The year is now 2024. Digital games, as we know them, originated in the 1960s (if we assign Spacewar! as the de facto beginning). That's more than half a century ago. Think about how old various pioneers will have been when starting out. The window of opportunity to preserve and understand the earliest days of video games is rapidly vanishing. Enthusiasts can only do so much, and are limited by free time, access, and money.

We need to follow Switzerland's example.