As part of our end-of-year celebrations, we're digging into the archives to pick out some of the best Time Extension content from the past year. You can check out our other republished content here. Enjoy!

The idea of video games on demand is something we're all quite familiar with today thanks to subscription services like Xbox Game Pass and PlayStation Plus, but what you might not know - and might even struggle to believe - is that Sega attempted its own version of this business model back in the 1990s.

Sega Channel, as the service was called, launched on December 12th, 1994, and was a partnership between Sega of America and the cable companies Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI) and Time Warner. It took advantage of a special adaptor, which connected to your cable box and plugged into your Genesis, to decode a signal that was zapped to your machine.

It was a revolutionary concept for the time, but one that failed to achieve the mainstream success that Sega had initially anticipated for it. So we wanted to take a closer look at this innovative service, the thought process behind it, and why it failed to catch on. To do this, we interviewed those involved with the project and searched through countless magazines from the period for any reference we could find.

This journey took us all the way back to 1993.

The Birth Of The Sega Channel

In 1993, Sega of America was riding high after reducing Nintendo's share of the video game market in North America. This was a market that Nintendo had previously dominated, but Sega was able to penetrate thanks to flashy marketing campaigns targeting teenagers. Everyone at the company, including Sega president Tom Kalinske, wanted to keep up this extraordinary momentum, so Sega tasked its vice president Doug Glen with finding a way to make the company look more "cutting edge" than its competition.

Glen went in search of some potential new technologies for Sega to invest in, and as luck would have it, the New York-based Time Warner was looking for a potential platform partner for an updated version of its Delta Box. This was a short-lived piece of technology, which had allowed users to download Atari 2600 games as part of their Time Warner cable subscription in the early 80s.

"The idea was cooked up pretty much simultaneously around Sega and Time Warner," says Glen. "And Tom Kalinske who was the head of Sega of America told me, ‘Doug, make it happen, and make sure it’s something reasonable and let’s do it because it’s kind of cool.

"Back in the early 90s, the conventional money was on interactive television," he tells us. "Time Warner had just completed an impressive trial in Orlando Florida with a true interactive television technology that was a precursor of what’s happening now but with a lot of technical differences. [...] It wasn’t as easy as calling up Little Caesar’s and telling them to hustle on over with a double-pepperoni, but the novelty was enough to get people interested."

Sega entered into negotiations with Time Warner as well as the Colorado-based cable company TCI, who also wanted to get in on the video game action. However, a deal wasn't exactly forthcoming. The three companies had initially tried to carve out a deal by courier, but no one could agree on the terms, so it was decided to take a slightly different approach.

Glen recalls, "I spoke with Geoff Holmes, our counterpart at TCI, and said, 'The only way we're going to do this is if we lock ourselves in a room. And we both happened to be in New York, so we said, 'We're not going to go home until we finally put pen to paper,' and it worked. We had the three sets of lawyers, we had the business leads from the company, and we came out of it holding this signed agreement high like the flag of Iwo Jima."

On 14th April 1993, the three companies announced Sega Channel to the world in a press statement. This statement claimed that the service would be launched in test markets the following fall and suggested that it could be available to US cable operators by early 1994.

At the time, Tom Kalinske, the former Sega of America president and chief executive officer, said of the service, "Everybody comes out ahead with the Sega Channel. The consumer gets an extraordinary value a (sic) well-stocked and constantly updated library of games for a low monthly fee. Once subscribers and their friends enjoy a game or preview, they'll be more likely to buy the packaged version so retail sales will increase. Our intellectual property licensors, developers, and third-party publishers will gain a new source of revenue. And Sega, Time Warner, and TCI will have begun working together on new ways to deliver mass market interactive entertainment in the radically evolving telecommunications infrastructure of tomorrow."

A Technological Bump In The Road

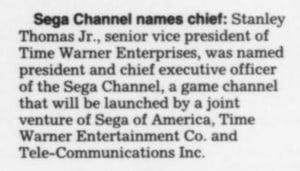

When this announcement was initially made, a leader for the joint venture had yet to be decided on, but only one month later, on May 20th, 1994, an individual named Stan Thomas was given the role of Sega Channel president.

Thomas, a Yale graduate, had been with HBO for 11 years before becoming a senior vice president at Time Warner and was a popular choice for president. He was one of the few black senior executives working in emerging technologies at that time and was known for his hands-off style of management, as well as for his incredible charm and charisma.

With the pieces falling into place, the remainder of that year was spent designing the adaptor and putting in place the infrastructure required to deliver Sega Channel.

"We got Time Warner's technology lead Andy Rifkin on board and we all met up in Redwood city where Sega headquarters was and we drew up a game plan," says Glen. "We had a couple of the engineers from Tokyo come over, because, in order for a set-top box to talk to a Sega Genesis, the box had to understand how the handshake occurred between the Sega Genesis and the cartridges. And if you’ve done much with Japanese technology companies, you’ll know they’re very secretive about how the technology works."

Andy Rifkin adds, "Everybody inside Sega US was incredibly cooperative, but when it came to Sega of Japan, they were kind of reluctant to share things with us. So sometimes we had to back-engineer things. They kept a lot of things very, very close. And they didn’t want to share. It was a challenge, but mostly it was a challenge because there were very many versions of the same unit that had different technical features that we had to emulate, so the box needed to work on a wide variety of platforms so we wouldn’t have to worry about which version it plugged into."

One employee we spoke to, however, contested that the Japanese engineers held anything back, calling it a "stereotype of Japan that needs to be dissuaded".

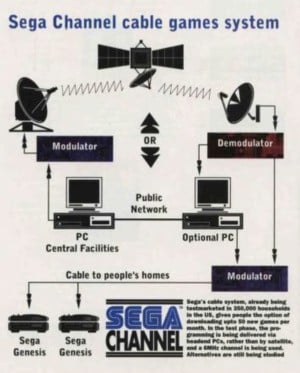

Regardless, the technological aspect of Sega Channel took longer than expected to get right. And because of these setbacks, what the team had originally expected to take six months ended up taking up to a year, leading to the fall deadline being pushed back. Nevertheless, the team eventually managed to set in place the technology and the distribution method for delivering this ambitious service over cable in the US.

This involved burning a new CD every month with the latest selections of games and any additional content and then delivering that by hand to the TCI satellite station in Denver, Colorado. The signal would then be fired up to the Galaxy 7 satellite, and then sent back down to a headend, before being re-transmitted to your adaptor that acted as a decoder. In some cases, the satellite portion of delivery would be skipped out, with the CDs simply being passed on to the cable provider itself to put in their system. The company responsible for manufacturing the adaptors and the headend equipment was Scientific-Atlanta.