This feature originally appeared in the excellent book Grand Thieves & Tomb Raiders: How British Video Games Conquered the World by Magnus Anderson and Rebecca Levene and has been republished here (in an edited format) with kind permission.

Arguably Lemmings could be thought of as one of the most violent video games of all time. It revels in thousands of graphic deaths per hour, animals are sent to the slaughter in cruel traps, and a frustrated player can unleash an apocalypse that kills all of them in a string of furry pops. But the lemmings die with cute squeaks, and are tiny. And when the violence is too small to be real, it seems developers can get away with a lot.

When Keith Hamilton, a software engineer writing code for credit card terminals, interviewed for a new programming job, it wasn’t even particularly clear what the company did. The location was an anonymous building in Green Park, Dundee’s main industrial estate, and there were few clues in the company’s name, DMA Design. But it didn’t take long for the pieces to click.

Things were made up as they went along. It was a fast-growing company, quite chaotic. I enjoyed it!

The interview was conducted by David Jones, by now an industry celebrity, and Mike Dailly. They were looking to replace Russell Kay, the man who had named Lemmings, but had since left to start his own development company, Visual Science. Hamilton was taken on to write Lemmings 3: All New World of Lemmings.

'It was my introduction to the industry,' says Hamilton, ‘to the chaos that it was.’ He had left a company making payment systems, one that could scarcely have been more security conscious, and come to a developer in a continuing state of anarchy. ‘Things were made up as they went along. It was a fast-growing company, quite chaotic. I enjoyed it!’

DMA’s first Lemmings sequel had been a decent seller, and the plan with the third game was to focus on more detailed lemmings. But somehow the magic was lost. ‘The lemmings were effectively bigger – I think that spoilt it,’ says Hamilton. Jones agrees, ‘I couldn’t think of any new way to take Lemmings at that point.’ The third game ended DMA’s six-title exclusive deal with Psygnosis, and meanwhile Nintendo had been courting DMA – the Japanese company needed imaginative, top-quality launch titles for its new rival to the PlayStation, the Nintendo 64.

DMA always worked on several projects at once, but there was no doubt what the most prestigious game in the stable was. The Nintendo 64 promised state-of-the-art 3D graphics that would shame the PlayStation, and DMA had designed a pioneering game to exploit them. Body Harvest was a science fiction adventure with a gruesome theme – aliens harvesting human flesh – and a compelling gameplay hook. Once the player had landed, they had complete freedom to find their own way around the levels, which were so large that they would need to commandeer vehicles to navigate them. Body Harvest promised to be revolutionary and the competition to be on the development team was fierce.

Keith Hamilton, however, was assigned to DMA’s other project. Race ’n’ Chase was the working title of a cops-and-robbers game for the PC. It wasn’t well formed yet, but it was already apparent that it would use conventional, even outdated graphics technology. ‘We hired a big team of mostly inexperienced people,’ says Hamilton. ‘Which was a very dangerous thing to do when you look back at it. But hiring experienced games programmers wasn’t possible, there just weren’t any.’

So there was a certain character to the Race ’n’ Chase team. They were overwhelmingly young, mainly recent graduates, and almost everyone was in their twenties. None of the group had children, or real commitments, and every single developer was male. Hamilton is unambiguous on whether this informed the design choices for Race ’n’ Chase. ‘Absolutely,’ he says. ‘Yes.’

Conventionally, games are pitched at publishers with a written brief and a demo. Instead, the Race ’n’ Chase team filmed a schlocky crime movie, with the developers as the stars. ‘We staged car chases round the streets of Dundee,’ recalls Hamilton. ‘We didn’t especially close streets or anything, we just had people at either end watching out for when it was safe.’ It was intended to show the mood of the game: gangster-themed car chases, cops and criminals, shootouts. ‘We had guys hanging out of windows pointing guns at each other, and it was just the programming team.’ As far as he can tell, a copy of this has never surfaced.

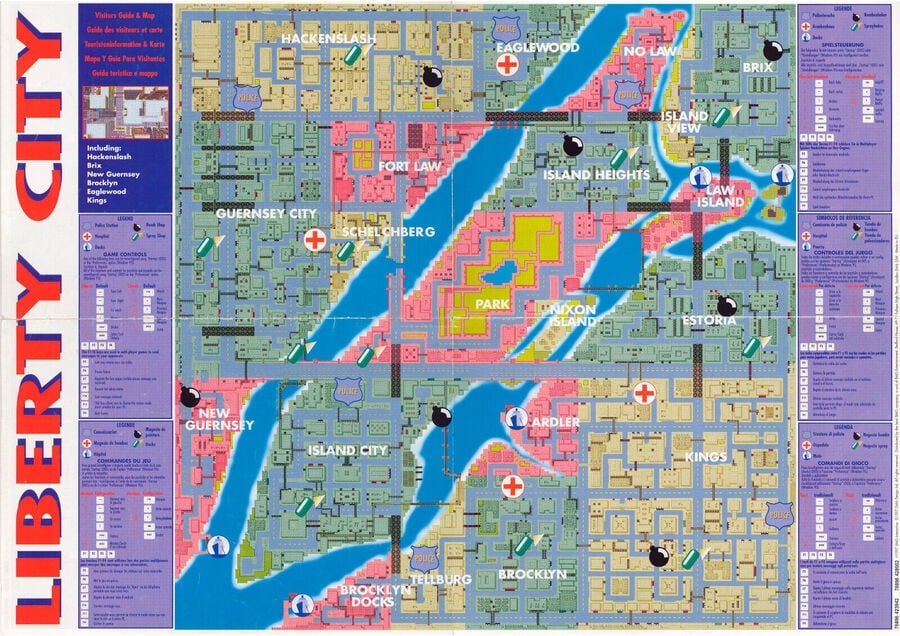

Race ’n’ Chase morphed and mutated over its development, but at its heart there was always a simulation of a city. The design was low-tech – Mike Dailly devised a graphics engine with an old-fashioned, overhead view. The player looked down on the cars, about an inch long on the screen, as if from an imaginary helicopter hovering above the road. There was some 3D in the design: the buildings swept past as the player drove a car, and the view zoomed out to show more of the road as their speed increased. But it was a primitive aesthetic, a league behind the already fashionable technologies for immersive, first-person gaming. At first sight, Race ’n’ Chase had more in common with elderly 8-bit games such as Spy Hunter and Micro Machines.

But this impression of primitivism hid Race ’n’ Chase’s true aspirations. It was a fantastically ambitious game where the city was coherent and filled with autonomous inhabitants. Traffic obeyed laws and drove with purpose, queuing at red lights and pulling out of the way as an ambulance drove by blaring its siren. Pedestrians wandered the pavements, jumping from the path of oncoming vehicles and fleeing scenes of violence. It felt like a real environment – the city had a soul.

Moreover, the player wasn’t locked into a car; they controlled a human character, who wandered the streets just as the other pedestrians did. But players could also climb into cars, and when they did, the whole city responded. Even in early versions of the game, the spark of ingenuity was there. ‘You need that, to make you think that it’s a real place,’ says Hamilton. ‘Almost to make you think that if you turn it off the city’s still there, that it’s carrying on without you.’

I remember when I played the game, I used to stop at the traffic lights and drive within the speed limits. Nobody else bothered. It was more fun to break the law

As the game was developed, the simulation became ever more comprehensive, producing effects the player might never even notice. ‘If you run somebody over, the ambulance does actually come all the way from the hospital, and wee guys pick them up on a stretcher, take them into the ambulance and drive all the way back,’ explains Hamilton. ‘Unless obviously you interfere and crash into it or something.’

And that was where the technology trade-off was spent. Race ’n’ Chase’s as yet unproven team were very conscious of the competition. ‘At the time, we were quite envious of the technical prowess of Carmageddon,’ says Hamilton, but there was little chance of them matching it. In any case, simulating the workings of a city instead of detailing its appearance was a deliberate decision. ‘Processor time is always precious – we wanted to spend it on the simulation of the world,’ says Jones.

In the brief for Race ’n’ Chase, and the first versions that DMA built, gamers could choose whether to play as a police officer or a criminal. But the team quickly found that playing the good guys was tiresome – every pedestrian became an obstacle, every traffic law a bind. ‘I remember when I played the game, I used to stop at the traffic lights and drive within the speed limits,’ says Hamilton. ‘Nobody else bothered. It was more fun to break the law.’

Once given the freedom, DMA found that players kept steering away from law-abiding decency. ‘It wasn’t that much fun playing cops,’ says Jones. ‘It felt like the game was working against you. When you switched places, it just felt so much better.’ For a while the design team persevered, with the player offered both sides of the law. But the pull of immorality was proving irresistible; in the team’s offices, nobody was playing as the police for fun.

Eventually DMA capitulated to the real draw of the game, and Race ’n’ Chase became an arena for improvised criminality. There was an undeniable, mischievous pleasure to be had from goading responses from the simulated city: sending traffic dashing out of your way, letting loose with weaponry and watching the pedestrians panic. A reward system was put in place that made crime pay. Running over pedestrians and stealing cars clocked up points, shown as dollars, which unlocked new missions and cities.

The cops remained, but now they were a balancing mechanism. As the player committed crimes, they would generate a ‘wanted’ level, and police cars would give chase. The attention of the authorities escalated in line with the player’s errant behaviour, until the whole army, complete with tanks, was in pursuit. It could bring on a delicious sense of rising panic where frantically evading the police for a small misdemeanour could lead to larger crimes, and an innocent skirmish could turn into a thrilling, city-wide pursuit.

Elite was one of the favourite games of mine when I was developing GTA, and I would certainly cite it as an inspiration. You could argue that it was the first open world. You could fly anywhere you wanted in Elite and you could pick up missions. It was pretty advanced for its time

Originally, Race ’n’ Chase had a formal mission structure. The player was tasked with killing certain targets, for instance, or delivering a package without drawing police attention. Once the task had been completed the player would be dropped out of the game, back to a menu screen. But this broke the flow, and meant that the consequences of the player’s delinquency were never followed through. In an inspired twist, the team built the missions into the fabric of the city – jobs were collected from phone booths and activated at the player’s discretion. And importantly, the city lived on outside the missions: if the player wanted to cause mayhem for fun, there was no time limit or objective to divert them. For all that completing missions was essential to progress, the foundation of the game had become unstructured, indulgent criminality.

And one crime above all the others gave the game its identity. There were dozens of vehicles in the city, and each required different handling and tactics. A light sports car could whizz the player away from the trouble he had caused, while a heavy truck could ram through traffic. Dailly made sure every vehicle was available to the player; with a single key press, the character on the screen would pull open the door of a nearby car, yank the driver onto the tarmac, and enter the vehicle. It was a transformative feature, not merely an entertaining animation or a way to rack up points, but a complete shift in the scope of the gameplay. Now any street offered a toy box of getaway motors and the tools for causing pandemonium. It gave the game its pillar mechanic, and its new name: Grand Theft Auto.

In 1997, gaming was still a young medium, yet it was already rare for a game to offer something novel. But Grand Theft Auto did just that, by creating a sense of the world’s persistence and autonomy, and in the way that it supported and was disrupted by freeform, improvised play. Hints of these innovations had been seen in previous titles, but here they met in a captivating blend – it was only after this game, and its successors, that the industry would look to name the new genre. ‘Open world’ gaming is one frequently used description, ‘sandbox’ another, and Grand Theft Auto is acknowledged, with barely any murmur of dissent, as the form’s chief pioneer. ‘I’d never heard the term sandbox before,’ said David Jones. Few had.

But Grand Theft Auto had influences, and one game in particular is mentioned repeatedly. ‘Elite, yes, yes!’ says Hamilton. ‘Elite was one of the favourite games of mine when I was developing GTA, and I would certainly cite it as an inspiration. You could argue that it was the first open world. You could fly anywhere you wanted in Elite and you could pick up missions. It was pretty advanced for its time. Yeah, that was a great game.’ In some respects the comparison is uncanny: wanted levels and provoking police attention, using money as the score, the possibilities for causing unstructured havoc. Elite’s co-writer David Braben understands the connection: ‘The first time I think someone “got” why Elite worked well was when [DMA Creative Director] Gary Penn told me about Grand Theft Auto – which he described as “Elite in a city”.’

Grand Theft Auto was a team effort. Hamilton was the lead programmer, Dailly designed the look and feel and Jones was the creative director. But ideas and features fell out of the chaos of development and anyone on the young team could add more. It was a style that suited their new gameplay. ‘Sandboxes are very simple,’ says Dailly. ‘Put some toys in a world then leave it alone! But hanging it all together as a game with levels, that was the evolution that the whole team contributed to. They were the ones who ultimately designed GTA, based on day-to-day playing, coding and what they thought would be cool.’ Their outrageous additions included tanks, rocket launchers, and a bonus multiplier for using a police car to run over pedestrians. The movie Speed was still fresh in their minds, and the player was encouraged to cause havoc driving an ever-accelerating bus.

Grand Theft Auto’s most notorious moment was a contribution from Hamilton. ‘I remember driving around in Glasgow and seeing “Gouranga” sprayed on a bridge and just wondering what it meant. And looking that up gave us the idea.’ The word is used as a chant by the Hare Krishna movement, who believe it brings luck to those who say it. From the moment Hamilton learnt that, a row of chanting Hare Krishna monks would occasionally appear on the pavements of Grand Theft Auto’s cities. If a player’s car mowed the entire chorus line down, the word ‘Gouranga!’ would fill the screen, and they would earn a bonanza of points. It had the makings of a controversy. When asked if he expected the outrage that Grand Theft Auto spawned, or that it might warrant questions in the House of Lords, Mike Dailly said, ‘No, although we did think it was funny.’

I remember driving around in Glasgow and seeing “Gouranga” sprayed on a bridge and just wondering what it meant. And looking that up gave us the idea

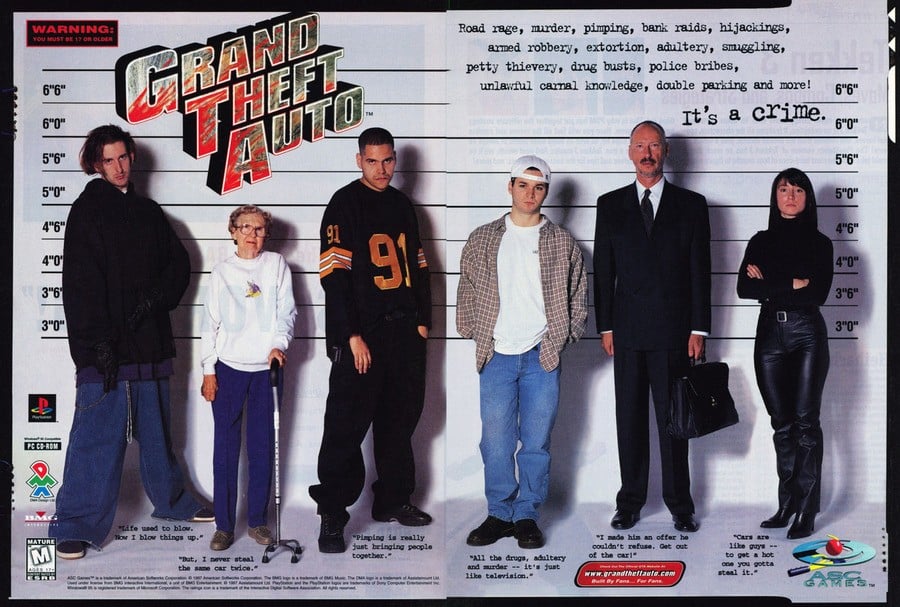

Dailly might have guessed, though, given that the indignant headlines in the newspapers and the moral grandstanding from politicians had all been orchestrated at the request of DMA’s publisher. After the Psygnosis contract had ended, Jones negotiated another multi-game deal, this time with a publisher that was new to games, BMG Interactive. It was part of the Bertelsmann Music Group, then attempting to manoeuvre its way into this new medium. BMG hadn’t been deeply involved in the development, mainly trading feedback on the increasingly refined builds that DMA sent to London, but it had been supportive of the game’s amoral tone. To Jones, BMG’s team felt like music promoters who treated the antisocial streak in Grand Theft Auto in the way that they might any other controversial property. And they understood marketing.

‘Their word for me was, “We’re from the music industry, and we’re used to dealing with acts all the time, with acts like the Sex Pistols and so on,”’ says Jones. ‘You know you’re going to get an outcry, and the way that they treat that in the music industry was that you embrace it. You make that part of the marketing.’

Over its development, Grand Theft Auto had turned into tabloid bait, yet this was the first time that Jones had realised the provocative content would be spun into the marketing campaign. He had no qualms about that, but it felt brave. ‘I think no other publisher would have done that,’ he says. ‘They’d be more worried about having an injunction slapped on them or something. BMG were just absolutely not.’ BMG’s strategy could not have been further from evasion. The company hired Max Clifford, Britain’s most talented public relations showman, to promote the game. Clifford would later be jailed in 2014 and indicted for eight counts of assault and passed away in 2017 – but in 1997, he was arguably at the height of his powers.

Clifford was famous, and sometimes infamous, in UK media circles. He had an intimate understanding of the processes and interests of newspapers, and fed his clients to them. Clifford’s public breakthrough came when he persuaded the Sun to run the front-page headline 'FREDDIE STARR ATE MY HAMSTER', which, though untrue, revived the comedian’s career. More recently, the country’s most famous publicist had become associated with political scandal, representing cabinet minister David Mellor’s mistress Antonia De Sancha and enlivening her story with lurid details. As DMA found out, he was a master of his trade.

‘I remember the meeting with him, it was quite a moment,’ says Jones. ‘We described everything you could do in the game, and he said, “That’s great, I understand exactly what you’re facing. Here’s how we’ll basically just leverage it.” He told us how he would play it out, who he would target, what those people targeted would say.’ He guided Jones through the plan: which politicians could be relied upon to react in public, which papers would join the reactionary fervour, how stories could be planted, how long they could last and how the story would snowball. Clifford knew the media system, and how to play it. And, according to Jones, ‘every word he said came true’.

In May 1997, half a year before it was due for release, Grand Theft Auto came to the attention of Parliament. Somehow word had reached the House of Lords that a scurrilous game was on its way, and questions were asked by Lord Campbell of Croy: ‘Is it true, as reported, that that game includes thefts of cars, joyriding, hit-and-run accidents, and being chased by the police, and that there will be nothing to stop children from buying it? To use current terminology, is that not “off-message” for young people?’ Not really, as it turned out. Lord Campbell’s feature list was remarkably similar to BMG’s own marketing campaign.

We were partly a bit naive at the time, not realising the power of what we were creating, but I still don’t believe that there’s any harm in it

In November, days before the game appeared, the headlines started rolling in. From the Daily Mail: 'CRIMINAL COMPUTER GAME THAT GLORIFIES HIT AND RUN THUGS'. And from the News of the World, simply: 'BAN CRIMINAL VIDEO GAME'. There were more thoughtful articles in The Sunday Times and Scotland on Sunday, but they raised the same fears. And those fears looked uncannily co-ordinated.

‘Max Clifford was the real genius here,’ says Dailly. ‘He made it all happen. He designed all the outcry, which pretty much guaranteed MPs would get involved. He’s not called a media guru for nothing.’ He even planted stories. A developer’s minor car scrape became a driving ban for a ‘Sick car game boss’ in the News of the World. A story circulated before release that thousands of copies of the game had been stolen from a warehouse. ‘Oh yes, I remember hearing that as well,’ says Jones. ‘Nice little plant story there. He would do anything to keep the profile high.'

The submission to the BBFC was part of the circus. Lord Campbell had specifically drawn Grand Theft Auto to the board’s attention in his speech to the House of Lords. The BBFC was concerned, and released a statement saying that the subject matter was ‘unprecedented’, but its claws had been cut by the Carmageddon scandal. The criminality of GTA was broader, and the urban rather than fantasy setting more relatable, enough to earn the game an ‘18’ certificate, but despite the concerns of the House of Lords, it was never seriously under threat from a ban. And the worries of Parliament were far from universal. When the matter arose in January 1998, Lord Avebury dryly entered the debate: ‘My Lords, is the Minister aware . . . that my twelve-year-old son, who has played the demonstration copy, assures me that he is not motivated to go out and steal cars?’

‘We never believed that it would actually cause that much trouble,’ says Hamilton. The controversy travelled word-wide – the game was banned in Brazil – but the development team never had a moment’s pause about the moral standing of their product. ‘We were partly a bit naive at the time, not realising the power of what we were creating,’ says Hamilton, ‘but I still don’t believe that there’s any harm in it.’

Grand Theft Auto had always been lightweight, tongue-in-cheek and a game before all else. ‘We knew why every decision was made, and we were never ever influenced by “let’s do something to create a bit of controversy”,’ says Jones. ‘We always did everything purely from the perspective of what’s going to be the most fun. It just naturally kept pushing down the darker direction.’

The moral panic that surrounded Grand Theft Auto was largely hollow, and mostly the construct of a PR consultant. It turned out that there were usefully malleable branches of the press, and even of government, who became effective if unwitting co-conspirators in seeking outrage and attention. ‘We tended to think of the politicians as idiots,’ says Dailly. ‘Complaining about a game that ninety-nine per cent of them would never have seen, let alone played. Calling it a murder simulator just showed how ignorant they were, and we knew it.’

Clifford’s campaign worked. Grand Theft Auto was a good game with some amazing innovations, but its retrograde look could well have sunk its sales. Instead it was known throughout the country as something illicit to seek out, and this was the vital impetus that convinced players to look past the graphics for long enough to appreciate the gameplay. In Britain the game sold half a million copies that Christmas. And around the world, it sold a million more.

Complaining about a game that ninety-nine per cent of them would never have seen, let alone played. Calling it a murder simulator just showed how ignorant they were, and we knew it

A little more than a decade later, in April 2008, Grand Theft Auto IV went on sale simultaneously across Europe and North America, and in its first week sales topped six million copies. That number eventually rose to twenty-two million, estimated to have earned its publisher and developer nearly half a billion dollars. But buyers queuing overnight for an early copy would find neither DMA nor BMG mentioned on the game’s packaging. And it had been a long time since the franchise had been made in Dundee.

In 1996, BMG had invested in DMA. Their four-game contract had cost them over three million pounds, and during the making of Grand Theft Auto, the publisher had left the games-maker to its work. ‘Yeah, that’s the way BMG set it up,’ recalls Jones. ‘Because they knew we were creative guys, and just trusted us to get on with it.’

But within BMG Interactive, factions were emerging. The company was splitting across the Atlantic, and across business cultures. According to Jones, ‘The guys in the UK were terrific to get on with – while we were developing GTA for a couple of years, everything was going great. It only changed when the US side of things took on a lot of EA people. So they had this kind of mismatch. Everybody in the UK was not from the gaming industry – they were from the music industry. So you had this kind of clash of cultures internally within BMG, which was kind of strange.’

Where the UK arm of the publisher saw the tempting prospect of milking controversy, the staff in the US had a classic games-marketing perspective. How did it look? Was it visceral? Was it cutting edge? ‘They thought this would never work in the US – that the consumer was too tech-savvy now, and they would look down upon something that wasn’t full 3D,’ says Jones. With only three months to go to the game’s American launch, BMG US was pushing to have it cancelled. It was only the appeals of the company’s London office that saved it.

But the relationship between DMA and BMG was still mixed. ‘The BMG deal as a whole was good and bad,’ says Dailly. ‘It did give a massive cash injection, and DMA’s size jumped from 50 or so to 130. It was also the beginning of the end . . . DMA took on too many projects, and this meant some didn’t get the staff and work they needed – a downward spiral in terms of cash drain.’

In the wake of Grand Theft Auto, DMA once again had a spurt of income, and the team were feeling very positive. Jones wanted to cement the success and reduce his company’s distractions from development. He brokered DMA into a takeover by the Sheffield-based publisher Gremlin Graphics. On the surface, it was a good fit. DMA was quirky and original, but successful. Gremlin, a publisher since the 8-bit computing era, was solid, and perhaps a little dull – its main range of games was a series of reliable sports simulations. Jones thought they would complement each other, an imaginative developer and a responsible publisher.

DMA’s acquisition by a publisher was permitted by its deal with BMG, but it complicated the relationship. In a sense, though, that was already moot. ‘Strangely enough, BMG had already made the decision to get out of the gaming business,’ says Jones. ‘They were in the process of closing down their US division, so Grand Theft Auto was actually then licensed to a non-BMG company in the US. Which I thought was a real shame, because they hadn’t had much success with gaming, and along came GTA and really started to trail blaze just as they were pulling out of the industry.’

The US licensee was ASG Games, which peddled the same controversy in America as BMG had in Britain. But ASG was a tiny publisher and the rights for the US PlayStation version that followed a few months later belonged to a larger company called Take-Two Interactive. Within two years all of these companies, DMA, BMG, Take Two and Gremlin Graphics, would have finished a complex game of musical chairs that would leave control of Grand Theft Auto with a new development team and a new boss, and on a different continent. ‘On the first GTA it was always BMG, there was no Take-Two,’ says Hamilton. ‘We had various people visiting from the US. It was quite late on before we actually saw Sam.’

We had various people visiting from the US. It was quite late on before we actually saw Sam

Sam Houser worked for BMG Interactive in London during the making of Grand Theft Auto. He was an English public school boy, the son of prestigious players in London’s swinging heyday – his father was one of the owners of Ronnie Scott’s jazz club, and his mother an actress who had played opposite Michael Caine in Get Carter. Houser had grown up connected to the media world, and had landed some work experience with the music arm of BMG while retaking his A-levels. After working his way through a slew of junior jobs in the company, including directing early video footage of Take That, he had manoeuvred himself into the division which he saw as the most exciting: computer games.

At first Houser was merely one of the BMG Interactive team reviewing the builds of Grand Theft Auto that DMA sent from Dundee to London every couple of weeks. He was a producer of the PlayStation conversion, but wasn’t well known to the Dundee team until after thoughts turned to a sequel.

GTA 2 transformed the franchise from an also-ran project for DMA’s new recruits to the star of its slate. ‘It was different now, in that we were no longer the unfortunate project of the company,’ says Hamilton. ‘We were now the big one that everybody wanted to be working on.’ GTA 2 had a bigger budget, and by now Sam Houser became involved. He was still based 400 miles away, but slowly becoming more visible. ‘I do remember him coming over,’ says Hamilton. ‘I remember a short, hairy guy. That would be Sam.’

There was a shift in the development style, too. Grand Theft Auto had been led by the design and technical aspects of the game: programmers threw in ideas, guided by the limits of the technology. For GTA 2 the technological framework was taken for granted and, as Hamilton observed, the game became more ‘artistically’ led.

Houser wasn’t a games coder, and in fact he had no computing background at all. But he was a games player, and a cultural sponge: during his teens he had immersed himself in hip-hop and East Coast rap. In this respect he was more BMG music than DMA games – his youthful interests rarely overlapped with those of kids who spent hours poring over code in their bedrooms. For the programmers, GTA 2 was about a more professional development cycle, and a complete technical rewrite of the code. For Houser, it was the chance to introduce gangs to the franchise. They were the subject of the game’s introductory video. Houser directed it himself.

Computer game development is volatile, and even in the glow of Grand Theft Auto’s sales, DMA, which had now opened an Edinburgh office too, found itself overstretched and resorting to desperate measures. ‘DMA had other projects that were not successful and that were burning a lot of money,’ says Hamilton. ‘My understanding of the situation was that Dave basically rescued the company by selling the rights to GTA to BMG, for enough money to keep the company going in its own right. It was a massive mistake when you look back on it, one that would be worth billions eventually. But we didn’t know that at the time.’

I never really saw eye to eye with Take-Two, to be honest, so I had to make a decision at that point. Did I then want to become part of Take-Two and stay with GTA? Or was it time to go and do something else?

Sam Houser rarely gives interviews, but every account of him suggests that when he is passionate about a subject, he is a juggernaut of a personality. In the midst of GTA 2’s development, Houser managed to persuade Take-Two to buy BMG Interactive, and they appointed him vice president in charge of both the UK and the US operations. Since the subsidiary could no longer be called BMG Interactive, and Houser wanted to keep it distinct from Take-Two, a new name was chosen, which would reflect the attitude of Houser’s new company: Rockstar Games. Grand Theft Auto was Rockstar’s premier IP, and when Houser chose to live in New York, the centre of gravity for the franchise that BMG had acquired from DMA moved with him.

Back in Dundee, Jones was struggling with another setback. Gremlin Graphics had sold itself to Infogrames, a rather conservative French publisher. Infogrames was unhappy about owning Grand Theft Auto in any form, not wishing to hold onto DMA Design for long, and in Rockstar they found a willing buyer. Keen to ensure that there were no loose ends to its ownership of Grand Theft Auto, Rockstar made Infogrames an offer. By late 2000, the IP and its developers had been reunited, and Jones found his former company and his biggest title owned and controlled overseas by an outfit he didn’t want to work with.

‘I never really saw eye to eye with Take-Two, to be honest,’ says Jones, ‘so I had to make a decision at that point. Did I then want to become part of Take-Two and stay with GTA? Or was it time to go and do something else?’ He decided to try something new.

Jones’s decision may have been affected by another wrinkle in DMA’s fortunes. The whole company agreed that a Driver-style Grand Theft Auto game was the next stage for the franchise, yet even within DMA there was a split. ‘There were two projects going on after GTA 2,’ says Hamilton. ‘There was “GTA 2 and a half ”, where we were taking the GTA 2 engine, making it in 3D, and setting the game in 1980s Miami. At the same time GTA III was underway, but being developed in the Edinburgh office, mostly by the team who had previously worked on Body Harvest.’

The new technology, and DMA’s geographical split, had resurrected the inter-team rivalry from the era of Race ’n’ Chase’s inception. And Take-Two’s buyout only seemed to heighten the division. ‘We thought this was Sam rescuing us,’ says Hamilton, but it quickly became apparent the Body Harvest team in the Edinburgh office were being favoured with the ‘real’ Grand Theft Auto sequel. Dailly, Hamilton and their colleagues were considering breaking away to form their own development company, when Jones approached them with an offer. He had secured funding for a new company in Dundee, would they like to join? ‘It was a case of choosing between Dave and Take-Two,’ says Hamilton. ‘And our loyalty was much more with Dave. The day after we left, they shut down the Dundee office and laid everybody else off, or moved them to Edinburgh.’

Even though their departure was their choice, it had felt like a necessary, rather than joyful, end to their careers at DMA. ‘It was a slightly acrimonious split,’ says Hamilton. ‘We were annoyed that the game had been given to this other team, most of whom had had nothing to do with the first two versions of it.’ Within a couple of years, DMA’s Edinburgh office, by then one of the most respected developers in the world, had been renamed Rockstar North. And the original DMA, the have-a-go Dundee start-up that had created Lemmings and Grand Theft Auto, had entirely dissolved away.

It was a slightly acrimonious split. We were annoyed that the game had been given to this other team, most of whom had had nothing to do with the first two versions of it

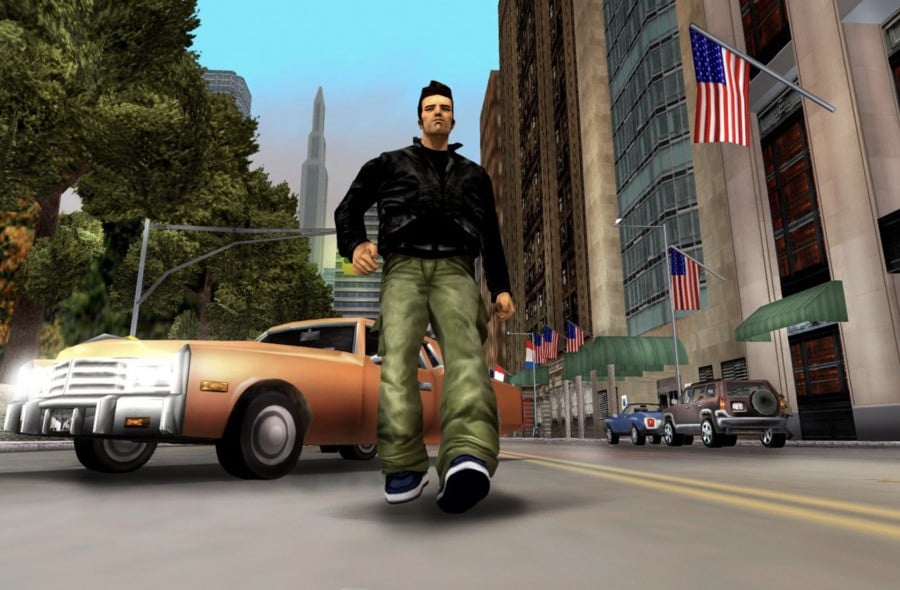

Grand Theft Auto III, published by Rockstar Games in New York and developed by DMA Design in Edinburgh, became the defining title of the PlayStation 2. It had a quiet launch. As big a PR splash as the first Grand Theft Auto games had made, their sales had been respectable rather than phenomenal, and modest things were expected from the latest sequel.

But once in the hands of critics, GTA III ascended to greatness. By the end of the PlayStation 2’s life, it had secured the highest aggregate review score of any of the platform’s titles. Despite only going on sale in the last two months of 2001, it became the bestselling game of the year in the US, and the following year its sales were beaten only by its sequel. It almost certainly helped console sales and it may even have reinforced the PlayStation’s victory over the rival Xbox, despite the game eventually being released for both. Around the world, GTA III has sold at least fifteen million copies. It was a breakout, suddenly mainstream game, but it had still been produced by a core team of no more than thirty, split between Edinburgh and New York. In the decade since its release, it has been repeatedly cited by the gaming press as one of the most influential games of all time.

‘When GTA III came out, it was galling,’ says Keith Hamilton. ‘Lots of people became millionaires out of it. And I didn’t, and neither did quite a few of the other guys on the original team.’ The former employees of DMA Dundee watched from a distance as the game became an unrivalled phenomenon. And it didn’t escape their notice that the setting of the abandoned ‘GTA 2 and a half ’, 1980s Miami, shared very similar themes to that of GTA III’s follow-up, GTA: Vice City. For the young team who had started their games careers on Grand Theft Auto, such alienation from their creation was a trial, but older hands found comfort in a longer perspective. ‘GTA 1 and 2 were big to be sure,’ says Mike Dailly, ‘but at the time they weren’t as big as Lemmings had been.’ Hamilton is sanguine about it now. ‘So be it, that’s what happens. You take your decisions at the time – there’s no point in regretting it.’

David Jones’ new company, grown from the ashes of DMA Dundee, was called Realtime Worlds. It produced what Hamilton calls the ‘real sequel’ to GTA 2: an urban superhero game called Crackdown. It was a long time coming, eventually arriving for the Xbox 360 in 2007, a generation later even than the PlayStation 2. But when at last it did, it won them a BAFTA. The team wore their kilts to collect it.

Grand Theft Auto became an international franchise. As the games became more successful, earning half a billion dollars per title, Rockstar was able to go shopping, acquiring development studios around the world, each renamed for its new owner and its location: Rockstar Vancouver, Rockstar San Diego, Rockstar London. But much of what gives the company its flavour – the voice acting, the IP deals, the city pored over as a model for the game – is American, albeit filtered through the vision of English public school boys.

Yet the development of Grand Theft Auto games remains more closely connected to Edinburgh than anywhere else. In Britain, and certainly in Scotland, there is a tradition of technical expertise that was first learned by bedroom coders. For all the corporate politics that moved the power behind the franchise across the Atlantic, the skill set had to stay in the UK.

And perhaps, at root, the migration is less a result of conscious intent, and more the irresistible draw of the game’s subject; Grand Theft Auto used the US as a setting from the start. Catering for the tastes of the world’s largest consumer market was certainly a sound business strategy, and arguably there was also a desire, long harboured in the music, film and fashion industries, to ‘break’ America. Or maybe the setting simply acknowledged that inter-national, media-rich games would find themselves pulled towards the world’s cultural centre of gravity.

The original Race ’n’ Chase specification included the waterways of Venice – they were only abandoned because changing boats was awkward. But the cultural reasons for setting the games in America were greater. ‘It’s set in the US mainly because the stuff you were doing was like things that you would see in films,’ says Hamilton. ‘And all films that you watched tended to be in the US.’

There was one last, compelling motive for locating this Scottish game in the United States, though: ‘For technical reasons,’ says Hamilton, ‘all the roads had to be at right angles. Simple as that.’

Please note that some external links on this page are affiliate links, which means if you click them and make a purchase we may receive a small percentage of the sale. Please read our FTC Disclosure for more information.