The names of the 14 weapon combinations also contained a number of obscure references and in-jokes. John’s Machine Gun SS was a reference to a weapon in the Capcom NES game Bionic Commando called Joe’s Machine Gun. The SS was an abbreviation of “Suganami Spirit.” Laser 100 was a reference to a series of Nisseki gas station TV commercials from the early 1990s that featured a type of high-octane gas called Racer 100. Lonely Soul Fire came about due to the insistence of one team member that the weapon be included. According to Maegawa, “Almost everyone was saying we didn’t need this weapon, but one person, maybe Kikuchi, insisted until the end that it was absolutely necessary.”

One of the weapons was given the nickname Shachō Laser (shachō meaning “company president” in Japanese). This weapon was the combination of the laser and homing weapons. When fired, it homed in on enemies without needing to be aimed whatsoever. The team viewed it as the easiest and most boring weapon available. Why was it called Shachō Laser? While assisting with the playtest process, Maegawa used this weapon exclusively, so the team named it after him.

Norio Hanzawa (alias “Non”) was assigned to develop the soundtrack to Gunstar Heroes. After working on Castlevania: The Adventure with Maegawa at Konami, Hanzawa had also created the music for the arcade games The Simpsons and Bucky O’Hare before joining Treasure in September 1992. He continued the musical style found in those games with Gunstar Heroes. Despite having never worked with the Mega Drive hardware before, he made expert use of the Mega Drive’s Yamaha YM2612 FM synthesizer chip to create fast and heavy rhythm- and bass-centered music, tied together with powerful melodies. The Gunstar Heroes music matched the gameplay perfectly; it was a constant barrage of sound, never slowing or letting up, full of vibrato. Alone, it was almost too much; Hanzawa joked in the Gunstar Heroes soundtrack CD liner notes, “Some people have complained that the soundtrack is too noisy, but it was really my first time working with the hardware, so please forgive me!” However, it served as the perfect backdrop to the frenetic on-screen action of the game.

Spreading The Word

As he recounted to Yōji Kawaguchi in 2017, on an early Spring day in 1993, Maegawa left the office of Treasure in Ueno and made his way to the upscale Aoyama district of Tokyo. His destination was the headquarters of Famitsu, Japan’s largest video game magazine. He carried with him a prototype of the first two stages of Gunstar Heroes, as yet unseen beyond the walls of Treasure and Sega. Maegawa, who was just 27 years old, was not sure what to expect. This would be the first test to determine whether his confidence had been warranted. It likely did not help his nerves that Famitsu had a reputation for not giving much attention to the Mega Drive, despite claiming industry-wide coverage.

Within the offices of Famitsu, Maegawa showed off the first two stages of Gunstar Heroes to one of the magazine’s editors. As the game progressed, the editor became more and more excited. After taking it all in, the editor abruptly stood, went over to a telephone, and made a brief call. A short time later, a second guest was shown into the offices of Famitsu: Sonic! Software Planning president Hiroyuki Takahashi. Takahashi was a somewhat regular face at Famitsu, dating back to his time as a producer at Enix doing promotional work for the Dragon Quest series. More recently, he had made visits to Famitsu to promote the new entries in the Shining series. He had not yet seen Gunstar Heroes.

The editor quickly took Takahashi over to the TV. Maegawa, who was familiar with Takahashi from his meeting with Sega president Hayao Nakayama and by general reputation, felt a jolt of excitement as the editor handed Takahashi the controller. The famous Hiroyuki Takahashi is going to play my own game in front of me! Maegawa thought.

Takahashi began to shoot his way through the Gunstar Heroes prototype, and his degree of excitement soon matched the editor’s. When the editor asked him what he thought, Takahashi could only reply, “This is incredible! This is going to be big. It’s like an arcade game!” The editor and Takahashi immediately began discussing how they could convince Hirokazu Hamamura, Famitsu’s editor-in-chief, to print a preview of the game – which duly appeared in the April 16, 1993 issue of Famitsu. The first page of the 'New Software' section was devoted to Gunstar Heroes—something unheard of for a Mega Drive game.

It was exceedingly rare for a publisher to allow a developer to independently promote its game. Maegawa was not aware of this at the time, but his later experiences taught him how unique Sega’s approach was—regardless of whether or not it was intentional. He told Yōji Kawaguchi in 2017:

I did all of the promotional work myself, including going to all of the magazine publishers. I was just starting out, so I thought that was normal at the time, but I later learned that it was very rare for a publisher to allow a developer to do this. For normal publishers, it was absolutely forbidden. “Don’t say anything to the media!” they’d say. Typically, the publisher would handle all promotional work since the game was being published under their brand. Sega, on the other hand, just let us do whatever we wanted, so I’m very thankful for that. I could go to all of the publishers directly and explain the game’s strong points myself. Sega is an amazing company for allowing that.

Maegawa acknowledged that this was probably not by design; at the time, Sega had just a single person doing this kind of promotional work for the Mega Drive in Japan: Tadashi Takezaki. The overwhelmed Takezaki was grateful whenever a developer volunteered to help out.

Sega’s hands-off approach applied not only to promoting a game, but also to providing development support. A normal publisher would often take an active role in the development process, closely following the project’s progress and supplying support staff when needed. “Sega gave us almost no support,” Maegawa told Yōji Kawaguchi. Although this might seem like a negative point, for Maegawa, it was the best possible outcome. He continued:

Their lack of support was actually a blessing. As I mentioned, when I made the company, I decided on the policy that we would make games that we ourselves liked. It turns out that there are very few publishers that will allow that. Sega basically paid us and then left us alone, so it felt like we could make whatever we wanted. What an amazing company!

The experience contrasted greatly with Maegawa’s later troubles with other publishers. Occasionally, publishers would send dozens of staff to provide development support, but from Maegawa’s perspective, this meant that Treasure lost control of the project. Sega’s lack of support, in contrast, allowed Treasure to maintain full control of its games.

Teething Troubles

Not everything went smoothly with the development of Gunstar Heroes. The team was under enormous pressure to deliver big on the company’s first original title, and they had no prior experience with the hardware. Maegawa emphasized how impressive it was that the company was able to release anything at all:

Our basic development system of the time had just two programmers, two designers, and two sound developers per team. The total timetable, which included setting up the development environment, researching the Mega Drive hardware, making the development tools, creating the game proposal, developing the game itself, and doing bug checking, was 10 months. That was all we could budget for. However, the morale of the original Treasure members was very high, so we were able to work at a rapid pace.

Despite their high morale, each member of the team expressed their frustration with the project in some way. “I really wish we had someone to do system support for the sound,” Yaida commented in 1993. “As the system programmer, I wanted to have some more flexibility. We ended up going over our deadlines, and it was all very difficult for us.” Iuchi was not satisfied with his background art for the game’s first stage and had to redo it three times. He recalled to Beep! Mega Drive Fan in 2019: “As a designer, the closest I got to the kind of colour usage found on the SNES was with the background of the first stage of Gunstar Heroes. However, as I made the backgrounds for each additional stage, I began to realize the Mega Drive’s limitations. The colours felt muddy or unrefined.”

Iuchi first began to experience negative health consequences towards the end of 1993 from the large amount of overtime the team was working. This would have major consequences for his later work at Treasure. The stress of the development crunch also seemed to have hit Suganami. Just as development on Gunstar Heroes was approaching the final deadline, he disappeared from the office for a period of weeks without any notice. Maegawa, fearing he might have died, tried and failed to find him. He eventually reappeared as if nothing had happened.

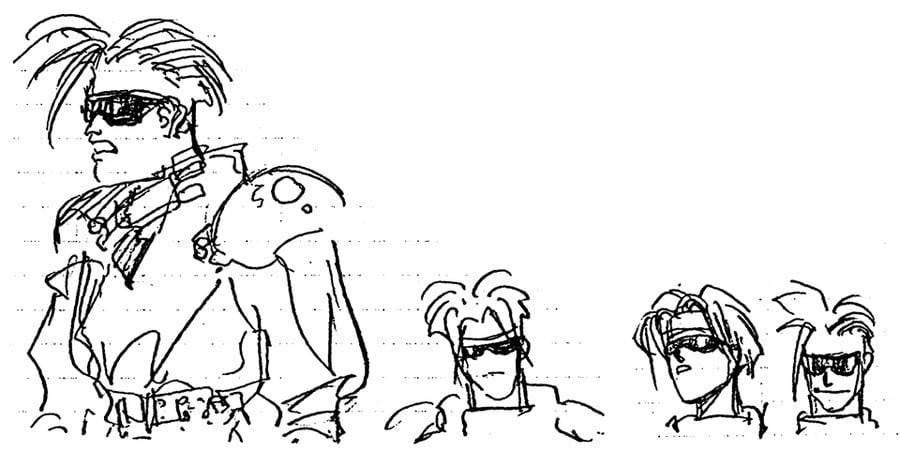

Kikuchi, who was working for the first time as the lead character designer on a game, struggled with satisfying his critics. In response to criticism from someone at Sega that the character designs were bad, he even drew “cool” versions of the characters wearing sunglasses. Speaking in Rakugakicho Compilation, he said:

Sega told me, ‘The characters are bad! Change them,’ so I drew versions wearing sunglasses. I even drew the pixel art. They weren’t popular among the development team, though, so in the end we went with the original designs. What a waste of time…

Such negative experiences created strife within the Gunstar Heroes team. Kikuchi hinted at this conflict, writing, “Fortunately, the reviews for Gunstar Heroes ended up being quite good. However, the experience developing it was completely unsatisfying. The team became divided due to internal strife and ultimately split up. But it’s also true that the game was completed through that conflict. It’s difficult to work together as a group.” Speaking to No Refuge in 1998, Iuchi also mentioned this conflict, saying, “The situation within the Gunstar Heroes team became quite volatile (laughs), so the team split up after development was finished.”

The specific nature of this conflict remains unclear, although there are some hints. Yaida recalled the challenge of serving as team leader for such a group of strong-willed developers; speaking to Beep! Mega Drive Fan in 2019, he said, “I was made the ad-hoc leader, but it was incredibly difficult to bring together the members, who all had such strong personalities.” Kikuchi, writing in 1994, provided some more details of his dissatisfaction with the game:

A great game can be made without me, and even if I’m there, that doesn’t mean the game’s going to be good. Now, I’m nothing more than someone supplying some art. The programmers made this game what it is, and even if I was involved with it, those who can see the truth know it. The only amazing thing about this game is the programming. The design is absolutely worthless. It’s obvious to me now that I’m completely unnecessary.

He would go on to say that a majority of the concepts and ideas included in Gunstar Heroes came from the enemy programmer, Hideyuki Suganami. In 1997, he told Sega Saturn Magazine that “Gunstar Heroes is a programmer’s game, where the main selling points are the multi-jointed characters. I’m not in a position to brag about how great it is… The only reason it turned out OK was because of the programmers.”

Localization

Once Sega had agreed to publish what was then Lunatic Gunstar, the prototype was sent to Sega of America to see if there was interest in releasing the game in the North American market. At the time, Sega of America had built up its domestic development capabilities to the extent that it no longer relied on games coming out of Japan. Games developed or produced by Sega in Japan, however, were still sent to the United States for consideration. A team of producers there played through the games and made the final call about whether to localize them, but there was generally no obligation.

When the Lunatic Gunstar prototype arrived at Sega of America, one of the first things that raised a red flag was the game’s name. “Lunatic,” it was decided, did not create a positive image. Kikuchi recalled what happened: “There were complaints from overseas about the word “lunatic” being really bad, so we had to change it.”

Meanwhile, the Lunatic Gunstar prototype was being passed around by the producers in Sega of America’s software development department. Each of the twelve or so producers was allowed to manage up to four titles at once, so any producer with availability could make the call to take on Lunatic Gunstar. However, the response to the game was very negative. By the time it reached associate producer Mac Senour, all of the other producers had passed on it. Senour’s boss, director of software development Clyde Grossman, was negative about the game’s prospects when he handed it to Senour.

Speaking to Arcade Attack, Senour recounted what happened:

I was last on the list. Clyde came to me and said, “Everyone else has turned this down. They don’t want to work on it. They don’t think it’s going to sell well. It’s up to you. So, it’s either you, or it goes in the trash.” So, I put it in, and I played it for about two minutes, and I threw down the controller on the floor. I said, “This is game of the year.” Mike Latham, who was sharing a cubicle wall with me, stood up… and said, “Mac, don’t say that… I turned that down. There’s no way.” I said, “No, I can take it. This is game of the year.” In hindsight, it seems that I was right, but at the time I took so much fire for that comment. I can’t explain it to you—the number of people that came by and said, “Mac, why would you say such a stupid thing?”

Grossman and the other producers at Sega of America were put off by the small size of the character sprites. At that point in the Genesis’s lifespan, there were a number of games coming out that featured large characters, and the producers feared that having such small characters in the game would make it difficult to market. Senour looked beyond this and focused on the gameplay itself. “They designed every level so well,” he said, “that you learn a new skill, and that skill allows you to accomplish that level. You go to the next one, and it builds on it.” As Senour saw it, the game required the player to constantly learn new skills as they progressed, so that by the end of the game, the player had a whole toolbox full of skills that they could use to play through the game again.

With Senour’s backing, Lunatic Gunstar would be released in the vast North American market, greatly increasing the game’s chances of selling well. This also meant that the title would have to be changed. The team came up with a second title, Blade Gunner, based on the 1982 film Blade Runner. Eventually, however, they would discover they could not trademark Blade Gunner. At that point, someone at Sega of America made a suggestion: Why not use the word “heroes” in the title? “They suggested ‘heroes’ since it’s a cool word,” Maegawa said, “so in the end we went with Gunstar Heroes. It’s a good, easy-to-remember title, although I’m still not sure that ‘heroes’ makes it cool!”

Once Sega of America had decided to publish the game, Treasure sent regular prototypes to Senour for checking. Senour recalled only a single problem he encountered with one of the prototypes. He was surprised to discover that a new boss had been added to the game—a boss that strongly resembled a moustached Hitler. This was presumably the first appearance of Smash Daisaku. Senour wrote to Treasure and told them that they needed to remove the character’s moustache. In the game’s next revision, the moustache had been removed.

There were no major changes to the game itself for the overseas localization. However, the story was significantly revised, going so far as to avoid all mention of the main villain Grey (even though he appears in the game itself). Instead, Colonel Red (Smash Daisaku) was made to be the main villain.

Release and Reception

Gunstar Heroes was released on September 10, 1993, in Japan, with North American and European releases around the same time. The game’s reception was overwhelmingly positive from both players and critics. Despite the very strong reviews, sales of Gunstar Heroes in both Japan and North America arguably did not reach their maximum potential. According to Maegawa's discussion with Yōji Kawaguchi in 2017, Gunstar Heroes ended up selling around 200,000 copies overseas in addition to the 70,000 copies sold in Japan.

The game received significant advertising in Japan, including a 15-second TV commercial and numerous magazine ads, but a problem arose prior to its release. Maegawa recounted to Yōji Kawaguchi what happened in Japan:

Sega had something like a built-to-order manufacturing system for Mega Drive software. I had been told repeatedly by Sega that Gunstar Heroes was going to sell well, but they ended up getting very few orders from retailers. They changed their tone because of that and suddenly said it wasn’t going to sell well after all. I have a vague memory that the initial manufacturing order number was something really low, like 10,000 or 20,000 copies. Of course, the game sold out everywhere on its release day, so Sega had to order up numerous additional manufacturing runs. Due to the slow turnaround with manufacturing ROM-based cartridges, the risk of lost opportunity due to underestimating demand is extreme. When they told me that they were only releasing 10,000 copies, I was a bit shocked. That’s why, in the end, we only sold 70,000 or 80,000 copies in Japan.

With a manufacturing turnaround of possibly several months, Sega was unable to meet the strong initial demand for Gunstar Heroes. The longer it took to replenish stock, the fewer users would buy the game. They would instead buy it on the second-hand market or move on to something new.

In North America, the situation was even worse. Maegawa considered the North American market their primary market due to the general popularity of action games there. However, despite Mac Senour’s efforts to release the game there, Sega of America had decided not to give Gunstar Heroes any significant promotion. This first became apparent at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show 1993 in Chicago, where Gunstar Heroes was shown. Diehard GameFan writer E. Storm (AKA: Dave Halverson) described the situation:

You would think SOA would hype this one everywhere with TV and print advertising, but, instead, it was tucked away in the vast Sega area on a 13” monitor, where I’m sure many people didn’t even see what was definitely action game of the show. No big movie license, no big-name recognition and no dinosaurs on screen equals no big deal to Sega. They’re sitting on the action game of the year and don’t even know it.

Mac Senour, who ended up leaving Sega before Gunstar Heroes was released, recounted in 2017 what happened:

There was a constant fight between development and marketing at Sega. I had few friends in marketing and the fellow that was assigned to [Gunstar Heroes] had a bad track record with me. He asked for some changes to Taz for the Game Gear and I refused to make the changes, so he ordered fewer copies to be made. The game went on to sell over 1.1 million units, so he had a lot of egg on his face! With his ego so bruised, anything I touched was considered bad. And sadly, that meant Gunstar Heroes took a hit. It also was under ordered which is one reason it’s currently selling for about $80 on eBay. Clyde [Grossman] did a great thing for his producers. He told us to focus on making great games and leave the rest to him. But he didn’t control the marketing department so any issues they had, they created on their own. It’s been over twenty years and that marketing guy still avoids me at conventions. Childish behavior.

Despite the poor availability of the game in stores and the lack of advertising, Gunstar Heroes received tremendous support from video game magazines and ended up winning numerous awards. In Japan, it was chosen by readers of Mega Drive Fan as the Mega Drive’s game of the year for 1993. Gunstar Heroes also won Diehard GameFan’s overall Game of the Year award and Action Platformer of the Year award in the U.S.

This made a big impression on the Treasure staff. Diehard GameFan presented the award to Masato Maegawa in an interview the magazine printed; Maegawa was shocked that the game had performed so well in North America. "I didn’t know that our game was so successful," he told GameFan. "SOA never told us." With Mac Senour no longer working at Sega of America, presumably, no one took the time to notify Maegawa of the game’s popularity.

Talk of a sequel occurred in the wake of the game's success, but Treasure was keen to create new games. However, in the early 2000s, a minor miracle occurred: the original Gunstar Heroes team (sans Hiroshi Iuchi) reunited to create Gunstar Super Heroes on the Game Boy Advance. Developed over a period of three years and released in 2005, the game saw the return of Tetsuhiko Kikuchi, Hideyuki Suganami, Mitsuru Yaida, Norio Hanzawa, Satoshi Murata, and Kazuhiko Ishida. Gunstar Super Heroes was part-sequel and part-remake, and just like its predecessor, it pushed the hardware to the limit. It was one of the few instances of Treasure releasing a follow-up title, and it received widespread critical acclaim.

Most recently, Sega included Gunstar Heroes on 2019’s Mega Drive Mini in all regions. The game continues to be recognized as one of the prime examples of the 2D action genre, and Maegawa considers it to be Treasure’s representative masterpiece.

This feature is taken from John Harrison's Legends of 16-bit Game Development, a book which looks at the Mega Drive / Genesis output of Japanese studio Treasure. It has been edited down from the original.

Please note that some external links on this page are affiliate links, which means if you click them and make a purchase we may receive a small percentage of the sale. Please read our FTC Disclosure for more information.