The Manchester games studio Software Creations is primarily known as the developer of games like Solstice, Plok, and a number of licensed titles based on popular films and comic books. However, what you might not know is that between 1995 to 1999, it teamed up with both Nintendo of America and Nintendo of Japan to work on what eventually became a successor to Mario Paint called Mario Artist: Paint Studio.

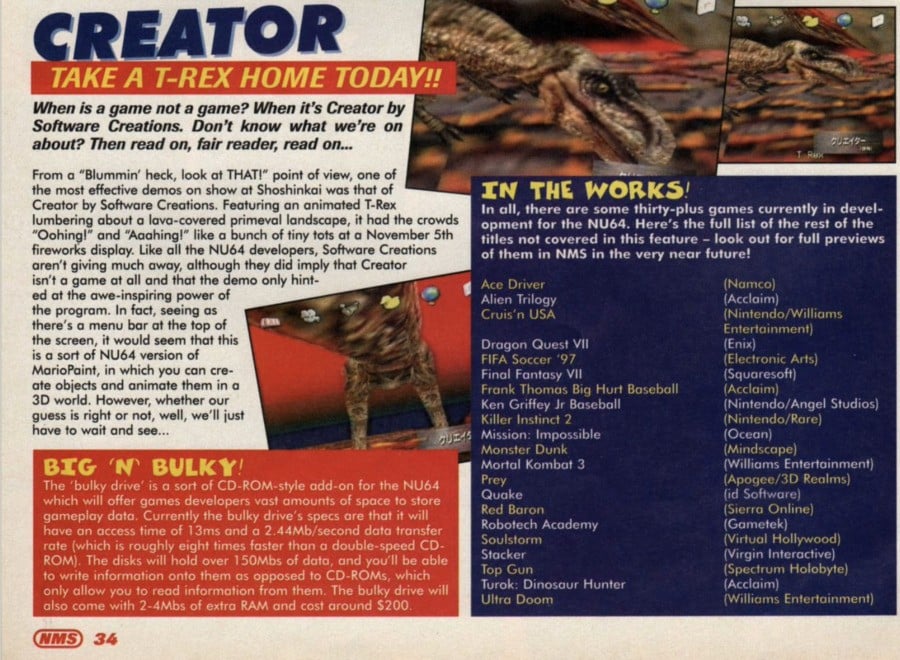

In 1995, Nintendo of America selected Software Creations as a member of its Nintendo 64 “Dream Team” — a group of studios brought together to design tools and games for the upcoming console. Nintendo tasked the studio with working on the sound tools for the Nintendo 64, as well as creating an N64 art application which was originally nicknamed Ultra Creator (or Creator for short). The project, however, wouldn’t end up being the most straightforward of productions, with the game shifting focus and direction several times throughout its development.

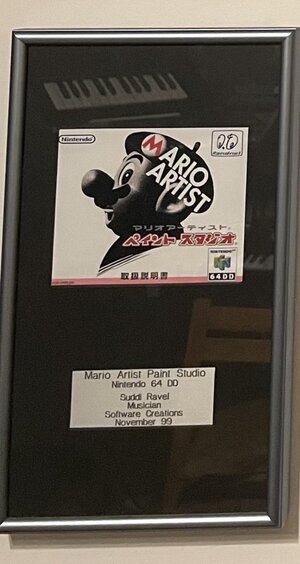

Mario Artist: Paint Studio launched on December 11, 1999, and was released as part of a suite of tools under the "Mario Artist" moniker for the Nintendo 64DD — a Japanese-exclusive peripheral that allowed users to insert 64MB magnetic disks for expanded and rewritable data storage. This meant that many of the people who actually worked on the game never had a chance to pick up a retail copy, only receiving a framed plaque for completing the project from their bosses.

This is a topic I've personally covered before in an article for the publication Fanbyte, but since then, I've managed to interview even more former Software Creations employees about the title’s long development cycle, ideas that ended up on the cutting room floor, and their thoughts on the finished product. Before we get down to discussing all the ins and outs of what the project actually was meant to be, though, it’s worth talking about the circumstances behind Software joining the N64 Dream Team in the first place.

Software Creations & Nintendo

In the late 1980s, Software Creations and Nintendo developed a tight-knit relationship after the studio's co-founder Mike Webb successfully reverse-engineered the Nintendo Entertainment System to create a custom development kit and started producing demos. Together with Richard Kay, the company's other co-founder, Webb reached out to Nintendo and eventually managed to sign an official agreement to become a licensed developer for the console.

"We were involved with Nintendo back in 1987," Kay tells us. "So I saw them in November ’87. Rare had gotten in before we had through a chap called Joel Hochberg. He did a lot of arcade stuff and he basically was their business manager. I think they were amazed that we turned up with this piece of hardware, plugged it into the NES, and that there was a demo – the very first iteration of Solstice. They were shocked, but it could have gone terribly wrong because it was their proprietary hardware. There’s no keyboard. It’s not like a PC. It wasn’t like a Commodore 64 where you could actually get in there and be used. It was never meant to be that. But you know, they said they were willing to work with people and were willing to take a risk on us, and from there, I had a great relationship with Howard and Minoru Arakawa."

Software Creations ended up releasing a bunch of games for the Nintendo Entertainment System and were among the first UK studios to get their hands on a development kit for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. As a result, they later ended up working with Nintendo on a few different games for the 16-bit console, including the platformer Plok (published by Nintendo in Europe), the sports game Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball, and the shoot 'em up Tin Star.

It made sense that once Nintendo was ready to launch the N64, Software Creations would be high on its list of trusted development partners. However, when Nintendo of America first revealed the N64 Dream Team in 1994, Software Creations' name wasn’t on the list. Kay, in particular, was furious at the snub, blaming the decision on a personal vendetta from a Nintendo of America employee who he claims was seeking a way out of Nintendo at the time and had been turned down for a job.

Kay recalls, “It didn’t make any sense because we had done Ken Griffey Jr. Baseball for Nintendo, and it had done really well. It had sold 1.2 million units and that was the year that there was a baseball strike […] So I phoned up Howard Lincoln and said, ‘This is bang out of order’. Howard just said to me, ‘We make decisions on what’s best for the company’, and I said, ‘So do we.’ The very next day we got a fax saying ‘Welcome to the Dream Team, we’d like you to work on the sound tools.’ So we got invited just on the fact that I got a bit arsey with Nintendo. And rightly so.”

The announcement of this collaboration between Nintendo and Software Creations was made public to the press in February 1995. Behind the scenes, Kay had entrusted two of his best musicians, Paul Tonge and Tony Williams, with developing the sound tools for the N64 dev kit, but there was also another interesting commission included in the fax. This was for a full-package music and graphics creator for the N64. So Kay gave John Pickford, one of Software’s lead designers who had previously worked on Plok and Equinox, the responsibility of coming up with the outline for this package, which was eventually nicknamed Creator.

Ultra Creator

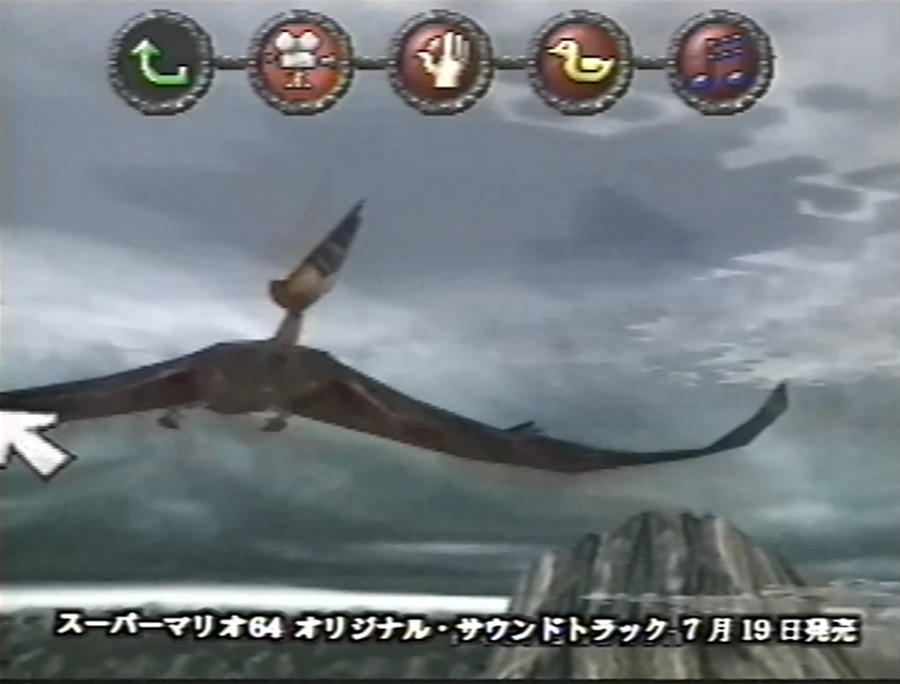

For the project, Pickford came up with the idea of having editable 3D worlds for the players to experiment and mess around in. Players would be able to alter the behavior, size, and appearance of creatures in an environment, and then witness the results. We tried to contact John Pickford to find out more, but he didn't respond to our request to be interviewed. Fortunately, though, the following summary of the project was previously made available on the Pickford Brothers' website and gives a little bit of an insight into this direction:

"John came up with a concept based on living 3D environments where the user could mess about with the creatures in the world – both editing the textures on the models themselves, and modifying the parameters of entities themselves – the physical size of a dinosaur, say, and its other visual attributes, as well as its AI properties such as aggression, speed etc. The result would be living playground where the player could mess around and play God."

In addition to the creature editor, mentioned above, there were also plans for a sound editor, like in the original Mario Paint, which would allow you to compose your own music using an existing library of sounds. In order to do this, Software Creations tasked a young musician at the company named Chris Jojo to build the editor, along with a programmer named Amir Latif (who had also been working on the music driver & composition tools for the N64 itself). Jojo had originally joined the company as an artist/musician, thanks to knowing someone working in Software Creation's quality assurance team, and had previously contributed to 16-bit titles like Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball, Spider-man & Venom: Maximum Carnage, and Tin Star.

"Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball was my first project at Software," explains Jojo. "Tim Follin had just left, and it was just [another composer] Matt Cannon and I. So I had to be trained to use the music sample editor. They were leaning on Matt to write music for Ken Griffey Jr., because they were falling behind in the schedule and I had my guitar with me, so we just started writing music as a means for me to learn the system and watch what Matt was doing. It was all hex-based, so you had to be careful with the frame count because every channel had to loop around. So if you had one channel out or an overlap you would start to get this delay and it would sound like a band falling down the stairs."

Reflecting on the plan for Creator, Jojo explains, “It was almost like Disney’s Fantasia. So you would have Mars, a prehistoric world, and an ocean level. I was asked to create a music editor with Amir targeting a younger market. Something ostensibly very kid-friendly. So it was just very basic building blocks of music. Creating a series of compositions, and then having the building blocks to create music efficiently and quickly. So it had scales and modes — diatonics for the harmony. And essentially everything was major-based, which was very much in the wheelhouse of Nintendo.”

Besides Chris Jojo and Amir Latif, two other musicians at Software Creations were also involved in composing the music for Creator. These included Martin Goodall and Suddi Raval. Prior to joining Software Creations, Goodall had no interest in computers but got the job following a chance encounter with Paul Tonge while performing trumpet in a big band. Raval, meanwhile, also had a bit of an unconventional entry into the games industry, having been a member of the acid house group Together (who were perhaps best known for their hit single "Hardcore Uproar").

"I knew Ste [Pickford, John's brother] for a long time through clubbing and knew he did games," Raval tells me. "But I had no interest in ever going into that industry. He used to buy my records and I met him at a rehearsal studio my friend owned, and he said to me, ‘I think you’ll be really good at making games’."

About the Creator project, he recalls, "We had this idea to give the player loads of different basslines and melodies in loads of different instruments as well, but make it so that no matter what you played on top of one another it always worked. So, it meant that someone had to write all those melodies and basslines, so I spent ages doing that just trying to make it work. We [also] had these computers called SGIs and I remember when we got them in, each one was worth hundreds of thousands of pounds and it was the only way of making 3D graphics at the time. It was before like 3DSMax and Maya being the way that they are. That really sent a message around the company that you know, this is a big-budget project because millions had been spent on just the hardware to make this game. So there was a real buzz about it."

Creator Debuts At Shoshinkai '95

Creator was unveiled publicly for the first time at Shoshinkai in 1995. For the event, Software Creations put together a prototype of the game, featuring an early look at a dinosaur world that featured a T-Rex walking around a volcanic 3D environment. This wowed publications at the time, including Nintendo Power, which wrote the following about the prototype in its January 1996 issue:

"Perhaps the most mind-blowing of all the software shown at Shoshinkai was Creator, a 3-D paint, music and animation program from Software Creations. [...] The realistic dinosaurs shown on tape were created in 3-D, and texture maps were chosen and applied. In the finished game, budding special effects artists will be able to create their own 3-D animated worlds and then control one of the characters. For instance, you could make an animated aquarium, fill it with fish and a shark, then swim around as the shark and eat the fish."

Coming out of Shoshinkai, the mood inside Software was positive, based on the reaction from the event and Nintendo of America's enthusiastic response, but there was some concern inside Nintendo of Japan over the direction of the project and whether there were enough game-like qualities to hook potential players. As a result, Nintendo of America eventually placed one of its producers, Henry Sterchi, on the project, in order to help guide the project and hopefully steer it in the right direction to win the approval of Nintendo of Japan.

Sterchi had been a tester on Rare games like Donkey Kong Country and Killer Instinct 2, and would later go on to help out on GoldenEye 007, Blast Corps, and Perfect Dark as a member of the Nintendo of America Treehouse staff. He was open to telling me a bit more about how he came to be involved.

“When NCL [Nintendo of Japan is referred to as Nintendo Company Limited by NOA] was really struggling to honestly make anything out of Creator, they had me take a look at it and see what I thought and what could be done with it,” writes Sterchi. “I came in far after the greenlight and was only aware that the next few milestones Software Creations had were very important and probably ‘make or break’ for the game. I focused specifically on helping Software Creations show they could execute on A. Their vision. B. A Nintendo Quality experience. When we attempted to add gameplay it became a little more like a safari meets “God game” but in a fun way, editing the scene and user creativity to create fun moments or outcomes on screen.”

Sterchi worked with Software Creations for the next few months, during which time new ideas were added such as a 3D protagonist (dubbed "Johnny Applecheeks" by some members of staff) and a camera system likened to Pokémon Snap that would allow players to take photographs of the creatures in each world.

The company put together an expanded pitch to demonstrate the game to several Nintendo dignitaries including Shigeru Miyamoto, Minoru Arakawa, and Howard Lincoln at E3 1996, with the Vice President of Business Development at Software Creations Lorraine Starr being the person responsible for presenting this demo to the influential figures. As she recalls, however, she almost blew the demonstration due to a sudden case of nerves.

“We went over to E3 and perhaps reading the book Game Over a few days before probably wasn’t the best idea!” Starr writes via email. “All the people I had been reading about were suddenly there in a meeting in a room the size of a toilet cubicle with about 12 bodies rammed into it. Nervous is an understatement. I was doing a demo but I had to stand so close to the monitor I couldn’t actually see anything on the screen and when I tried to take a step backward, I yanked the controller out of the back of the machine. Fortunately, our U.S. producer Henry Sterchi felt my pain and took over. Mr. Miyamoto was one of the people in the room and clearly liked what he saw.”

It was during this pitch that Nintendo of Japan saw the potential to transform Creator from a spiritual successor to Mario Paint to an official sequel named Mario Paint 64. This eventually led to a bunch of changes to the project, with Nintendo of Japan installing Mario Paint’s director Hirofumi Matsuoka as a lead on the project (with Takao Sawano as a producer), and Nintendo of America taking on more of a backseat liaison role between the two companies.

Mario Paint 64

Software Creations was now officially working on a Mario game, which excited many within the studio, but it also meant throwing away months of hard work in order to achieve Nintendo of Japan’s new vision for the project. Among the changes that were introduced were the removal of the AI editor, an increased focus on a traditional 2D paint application, and the implementation of mini-games (including Gnat Attack from Mario Paint), in addition to the controversial removal of the sound editor.

Behind the scenes, a small number of people started to leave Software for greener pastures. This included the project’s lead designer John Pickford, who left the company along with his brother Ste Pickford in late 1996 to start Zed-Two, and Amir Latif, who joined them to work on the video game Wetrix. On the Pickford Brothers' website, the following gives an insight into this particular period of time:

"The project was caught up in political infighting between NOA and Nintendo of Japan over who was controlling the project, and eventually the Japanese took control and rejected many of the ideas which had been accepted enthusiastically by the Americans, steering the project in a different direction after John left Software Creations to form Zed Two, and throwing away loads of work."

At this juncture, the musicians' focus shifted from building the sound editor to creating a bunch of music for the various worlds that were to be included — a lot of which never ended up making the cut for the final game or ended up being used in a slightly different context than initially anticipated. This included music for a cut Safari level, which was teased in various promotional shots supplied to magazines at the time.

Jojo recalls, “I could see the environments progressing, and I knew my responsibility was to create music for the different worlds. I think there were about 8 or 9 tracks per world. So I distinctly remember the African safari one, because there was lots of pentatonic harmony, you know African major/minor pentatonic scales. I really enjoyed that aspect of it. [I think in the end the Safari concept ended up merging with the Jurassic theme; the music's the same.] And for the sea world, I was doing like a Dick Dale, Ventures-like surf track. That old reverb, Fender, twangy guitar stuff.”

Suddi Raval and Martin Goodall also presented a lot of music that didn't end up being used as expected. For Raval, this was particularly heartbreaking, as he ended up spending ages trying to supply Nintendo with something he thought would be really special and be enjoyed by millions.

"I did a load of music for the world stuff," says Raval. "I don’t know if any of it got used. I’ve no idea at all. I was talking to Martin and he couldn’t find anything of his own at first and then he found something. And it was a little odd because he said it felt a little bit like someone had redone them. They’re his melodies, but it just sounded slightly different."

He continues, "That’s the real shame of it. Because given the opportunity to work on a Nintendo product, I was really excited about it and I wanted to do something special for them. I tried like loads of things for the underwater level in order to try and give Nintendo something that I think is going to be great because I felt millions of people would be playing it. I used to play this piano piece, which is sort of one of the first things I’d ever written and I never released it thinking I'd wait until either I needed it for something or it was the right time where I needed to compose something really special. So I had this kind of piano piece that I was saving for myself and yeah, I ended up giving it to this game (which I saw as giving it to Nintendo) [and it never got used]. It's the piece that’s actually online. I can send you a link to it. I put comments in there from seven years ago and I was asking the guy like, ‘How did you get hold of this?’ Because I didn’t even have it. I’d lost it."

In addition to requesting a bunch of changes to the game's design, Nintendo of Japan also decided to move the project from the base N64 to the N64DD — an unfinished peripheral that used magnetic disks to expand the system’s memory and that needed a killer app. This came with the added benefit of allowing Software to be able to save or write back more to the console than a typical N64 game, but the exact specifications and features of the peripheral were still undergoing changes.

Starr tells me, “Every time we were near completion they came up with a new feature, such as video capture and eventually the introduction of a mouse. The project [would then require] a re-design to incorporate each new feature.”

Some of the features Nintendo of Japan suggested around this time were the ability to use the 64DD's Capture cassette or the N64 Transfer Pak to import new images into the game, as well as the option to use the mouse to move the cursor for more accurate control.

Mario Artist: Paint Studio

Development on the game continued to drag on, and inside both Software and Nintendo, there was definitely the feeling that the project was struggling to come together into a cohesive whole. Shigeru Miyamoto, who acted as a supervisor on the game, for instance, acknowledged the “strange” nature of Mario Paint 64 in an interview with Dengeki N64 magazine in 1997 (accessed via IGN) where he also claimed, “many will say it’s not a game”. This would be one of the last times anyone at Nintendo would publicly acknowledge Mario Paint 64 in interviews, as soon after the project underwent another reinvention.

At Nintendo's Space World conference in November 1997, Mario Paint 64 reappeared as Mario Artist: Picture Maker (later to be renamed again to Mario Artist: Paint Studio prior to release). Nintendo’s new plan was to use the game as a tentpole release for a suite of interconnected art applications, released under the Mario Artist banner.

Other applications in this suite included Mario Artist: Talent Studio, an animation production tool; Mario Artist: Communication Kit, a way of connecting to Net Studio and sharing the creations from other games; and Mario Artist: Polygon Studio, a 3D graphics creator and renderer.

Speaking about the project in a previously untranslated interview (now translated by the freelance Japanese-to-English translator Liz Bushouse) with Famimaga 64 magazine from the Space World show floor, Miyamoto said about the project, "It's all about that ability to express yourself in a way that's fun. For example, I enjoyed drawing comics when I was a kid. And it used to be that people who couldn't draw just didn't pursue drawing, but now even those people can draw, and in fact, it's those kinds of people who possess great talent and artistic sense, so I want to incorporate that into play."

This new direction was apparently the push the project needed, as Mario Artist: Paint Studio finally released on December 11, 1999, as one of the launch titles for the 64DD. In the finished game, up to four players can paint or stamp Nintendo-themed stickers together on a single canvas, while those playing alone can explore the ocean, Mars, and prehistoric worlds — editing the textures of creatures, taking photographs, and generally mucking around. The finished game shares a lot of the same charm as other Nintendo products (even including a number of tracks from the famous Nintendo composer Kazumi Totaka), but it also arguably suffered from poor timing as home computers and creation tools were then becoming more ubiquitous than ever.

In one of the only English-language reviews at the time, Peer Schneider of IGN concluded: “Paint Studio is a well-put-together creativity tool that’s limited by the platform it’s on. If this were a PC app, I’d recommend it both as a low-cost paint program and an excellent ‘My First Photoshop’ edutainment title for kids. On the N64, it’s a dinosaur, a throwback to the SNES days — and an important reminder that there is a reason PCs and console systems are able to exist side-by-side.”

Interestingly one of the bizarre quirks of the IGN review is its mention of mini-games, which were actually stripped out of the final version of the game prior to release. It's possible that Schneider overlooked this removal when reviewing the game, as he had previously been at Spaceworld '97, where the Gnat Attack game was demonstrated to the public.

Nintendo had allegedly intended to release Mario Artist: Paint Studio in other regions at a later date, but poor sales of the 64DD eventually scuppered any chance of these plans. The 64DD sold way below expectations, with many estimating Nintendo only managed to shift 15,000 units, based on the number of subscribers to its Randnet online service. Nintendo never released the peripheral outside of Japan, and as a result, the developers at Software never got to play the game they had spent almost five years making.

“Sadly we didn’t get to play the game after release,” says Starr. “The N64DD was only ever released in Japan. We did get sent one copy and I think some of the team were able to get them via Ebay. It was pretty gut-wrenching but the experience of working with such talented people at Software Creations and Nintendo was unforgettable.”

What the team did get, however, was a plaque from their bosses at Software, acknowledging the work they did on the project.

Raval recalls, "Software Creations had this great idea of every successful game – because they were making a lot of money from the big licenses they were working on like The Simpsons and Spiderman and stuff like that – they’d frame a cartridge. Say, if it was a Game Boy game – because I did a lot of Game Boy games – they’d frame the cartridge and put the cover in the frame as well with a little plaque at the bottom that says ‘Suddi Raval worked on this game at this date at Software Creations.’ And it was really nice to have. I’ve got it on my wall in my studio and it looks great because I’m really proud of what I did. And with Mario Artist, there was no cartridge. It was just a frame with a little plaque that said, ‘Suddi worked on this game.’"

Now, with the internet and translated ROMs, it’s much easier for everyone to experience the results of Software’s labor, and the end result happens to be a fun and inventive creation tool, although slightly less ambitious than what Software originally set out to make.

As for Software itself, it was subject to numerous buyouts, before eventually closing its doors for good in 2004 — a sad end for a studio that contributed so much to Nintendo’s consoles and history over the years.

Reflecting on the fall of Software Creations, Chris Jojo says, "As things progressed, with each successive iteration of a console or new tech — going from 8-bit to 16-bit to streaming on disc-based platforms — the time it takes to establish those pipelines and all that new technology increases and there's a hike in the headcount as well. But when you have a roster of talent and you're cranking these games out and making money, and you've got a short turnaround, then you're going to get decent profits.

"That's why Richard Kay sold out his interests. He made his money. He worked very hard to get to where he was. And I think Mike Webb went the distance [with us]. He carried on with us through Software Creations into Acclaim and then he obviously took his hand off the tiller."