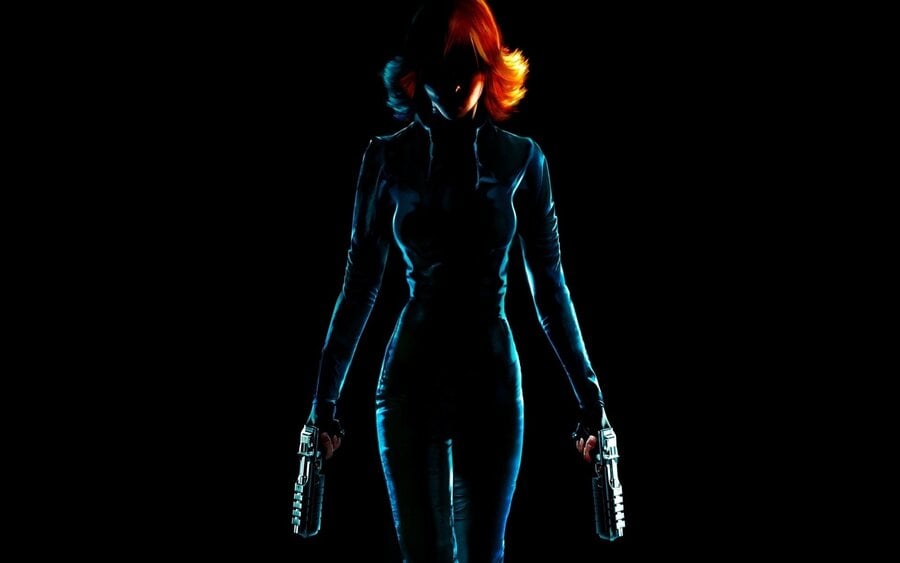

Given that the original Perfect Dark stands as Rare's highest-rated game of all time, a follow-up was inevitable.

The project began life on the GameCube (there was even a render of Joanna Dark in the tech demo reel at SpaceWorld 2000) before it was migrated to Xbox after Microsoft acquired Rare in 2002. But it wasn't until the debut of Microsoft's second console, Xbox 360, that the world finally got its hands on Perfect Dark Zero.

Five years after players were introduced to Joanna's world of spycraft and sci-fi, this prequel told the story of her first mission and her initial encounters with the evil Datadyne corporation. It was a long, hard slog to reach launch, with expectations raised by both its lineage and the pressure to demonstrate what Microsoft's next-generation machine could do for shooters raising expectations.

As with so many blockbuster games, it all came down to the final year of development.

Producer Lee Schuneman was brought on to the team in September 2004, 14 months before launch, to work with fellow producer Rich Cousins in "helping the team get to the [point of] shipping the game."

"Rare was tasked at that time of delivering two launch titles for the Xbox 360, and it was my unfortunate task to do both at the same time," he tells Time Extension, referring to Kameo: Elements of Power, for which he was executive producer. "It was a crazy hard project and definitely impacted my health by the end of it – trying to do two [games] with that sort of deadline and that sort of pressure was not fun."

Schuneman admits that expectations were high, partly because Rare set such a high bar for itself. "The Rare blessing and curse is [having] a great team of people that always had bigger ambitions than was maybe technically possible, and were always trying to push the boundaries of gaming in different sorts of ways. They never really had that many constraints with that in mind."

However, as talented as Rare's team was, on Perfect Dark Zero and Kameo they were working with a totally new platform – and that both increased the pressure and made development more challenging. "When you're responsible for a launch title, it's a different challenge," Schuneman adds. "Console launches need great software to get you to buy the console – that's the whole point. That pressure is there in the back of your mind all the time, because you have to deliver to a date and you're trying to deliver the best game you can to that date, and sometimes those things clash."

Console launches need great software to get you to buy the console – that's the whole point

Schuneman was also involved in bringing in more talent to help get the game over the finish line, including lead engineer and programmer Kieran Connell. A Rare staffer since 1997, Connell knew nothing about Perfect Dark Zero due to the studio's famous propensity for secrecy ("You only had the keys to your barn so you could really only speak to your team," he recalls). So, what state was the game after four years of development?

"It was… interesting," he laughs, recalling a playthrough of the game's rooftop level "looked beautiful but was a bit of disaster" – riddled with bugs, running very slowly and at just 480p. "The team had been working for a long time; they'd had a lot of code upon code upon code, so I can't remember if there was anything from the original GameCube [version], but certainly a lot from the Xbox version that had been dragged forward to the Xbox 360."

Given that the game had been pushed from platform to platform, it's little wonder that it wasn't in an ideal state. "There was quite a technology shift between the two pieces of hardware, and they'd had a lot of time to make content," says Connell. "So there was a lot of the game there, but it was in quite bad shape – very buggy, it would crash all the time, a lot of framerate problems. They'd got it up and running on the brand new Xbox 360 developer kits, but those weren't even the final hardware, just an approximation of what it was going to be."

I think Rare was also caught off guard by the generational shift and how much larger the teams would get

Schuneman feels that the game's legacy – which stretched all the way back to the N64 – worked against it, too. "The challenge with Perfect Dark Zero was that it was just huge, trying to do interesting things with massively multiplayer levels and a campaign – and of course following on from Perfect Dark itself, which was a follow-on from GoldenEye. It had this legacy challenge; it was trying to be its own game and trying to be something unique and different – and you're trying to ship for a launch time."

The rush to hit launch was a very different way of working for the studio. "We'd never really done launch titles before," Connell says. "Rare always had that 'it's ready when it's ready' sort of mentality. We'd happily miss Christmas in order to ship the right game at the right time, but Microsoft was very much wanting the jewel in the crown studio to deliver two titles – Kameo and Perfect Dark – for launch."

The internal pressure was also tough to contend with. The team had spent four years coming up with new ideas and features for Perfect Dark Zero to the point where the game was "sagging under its own weight," according to Connell.

"I think Rare was also caught off guard by the generational shift and how much larger the teams would get," he says. "The early N64 games had all been made by less than 20 people and by Perfect Dark Zero that had shot up to 80, and they weren't necessarily equipped for that. Suddenly, all the systems they had in place were creaking a little."

For instance, Connell had 14 engineers reporting to him – previous Rare projects had fewer people than that on the entire team. He also points to the three art disciplines – character led by Jonathan Mummery, background led by Sam Jones, and prop art by John Doyle – that were all using new technology, but remained "somewhat disparate." The result? Something of an uncomfortable mix. "They could have their art on their individual machine, but when it all came together, it didn't necessarily mesh in the same way," Connell explains.

We were using a lot of technology that was new to the team: Havok for physics and ragdolls, and multi-threaded systems and code, which generates lots of bugs

Schuneman says the final year of development didn't necessarily result in a lot of cuts, but was "more a case of prioritising what's going to differentiate the game and what we're excited about. Of course, the team thought everything is that," he laughs. "[It became] more about accepting the quality bar variation. We had to make some trade-offs, but that's true with any game. Any team would keep making the best game they could and would do it forever, but you've got to stop at some point."

Connell recalls that stabilising the game was the biggest priority. "Coming on after the game's been in development for four years, I can't change how they're doing certain things. We were using a lot of technology that was new to the team: Havok for physics and ragdolls, and multi-threaded systems and code, which generates lots of bugs. So really, it was about instilling processes to get on top of that, to prioritise, and to fix bugs rather than adding new features."

A lot of bugs, he says, were "actually written into the code" in a way that modern game engines and scripting languages would help teams easily avoid. Connell ended up pairing each designer with one of his engineers to improve the quality of the code and reduce the bugs found there. Rare even seconded Bungie's Mike Evans, a lead engineer from the Halo team, to help fix issues like memory leaks. Evans patched in some tools from the Halo engine, and Connell says Perfect Dark "would not have shipped without him."

Multiplayer proved to be a particular challenge. Following the impact of GoldenEye's multiplayer and the improvements made for the original Perfect Dark, this was always going to be a crucial part of Zero. Mark Edmonds, lead network programmer for the game and a key programmer on its two forebears, was instrumental in this, but, as with so many aspects of Rare design, it became a clash between ambition and reality.

Deep down, he wanted to make an MMO, always wanted to push the limits of how many players you could have in one place

"Deep down, he wanted to make an MMO, always wanted to push the limits of how many players you could have in one place," Connell recalls. "Super smart guy, he came up with his own networking system that could scale the number of players online to much higher than we would have had in that sort of era. And for the most part, it worked."

Edmonds' goal was to enable 64-player matches, and the team got very close to this on Rare's internal network. But as soon as they tested it online with the alpha and beta kits, players were either being dropped out or the entire game would terminate early.

"It was unshippably bad," says Connell. "At one point, we realised we'd have to cut it down to 16 players or something. At the time, we didn't have the tools to understand the network traffic. Very late on, Microsoft in the US did a full playtest and sent back an enormous log file, at least 2GB of logs. We spent a good few days just going through them."

These logs revealed that Perfect Dark Zero's networking system did not work with the way Xbox Live was set up. In the end, Edmonds had to completely rewrite the entire networking stack two weeks before the game shipped. "The next day's playtest, we had 100% completion rate with games of up to 32 players," Connell recalls. "It all came down to Mark's genius, literally at the last second."

Was I satisfied? Of course, because it came out on time

Perfect Dark Zero was released alongside the Xbox 360 on November 22nd, 2005 and was generally welcomed by critics, holding onto a solid Metacritic score of 81 to this day. Within a year, it had sold more than one million copies, earning a place in the Microsoft's Platinum Hits collection for the console. Of course, comparisons with its predecessor were inevitable – but, Schuneman suggests – somewhat unfair.

"GoldenEye and Perfect Dark were made by mostly the same team. They had a closeness and a connection and an ambition in place," he says. "The Perfect Dark Zero team was mostly not the same team; a lot had left to go start Free Radical. So, it was a different group, and therefore, they had their own ideas of what it should look like. There's not a direct way to compare them because it's not the same creatives as the driving force behind it. But then, being a shooter, being this ambitious title for Rare, and being a launch title, you can end up in a world where expectation is so insane you can't live up to it. But that's the nature of the video game business.

Ultimately, though, it all comes down to how the team felt about the game. "Was the team satisfied?" concludes Schuneman. "I don't know, you'll have to ask them. Was I satisfied? Of course, because it came out on time."