Sony's PS2 is 25 years old today, having launched in Japan on March 4th, 2000. We're republishing this feature to mark this amazing event.

Sony had a record-breaking year in 1998, raking in over $51 billion in sales and operating revenue. Profits from television sales had spiked in 1997 and continued climbing. Having recently released such notable flops as The Cable Guy and Striptease, Sony's movie studios turned a corner as well, releasing hits like Men in Black and Air Force One. Picking up where Walkman left off, Sony's Discman hit pay dirt in the United States, and its new MiniDisc audio format caught on quickly in Japan. Then, of course, there was the PlayStation.

Sony shipped four million PlayStations in 1995, 9 million in 1996, and 21 million in both 1997 and 1998. Nintendo sold fewer than 35 million N64 consoles during the console's seven-year lifespan. The Sega Saturn never reached 10 million. Sony was one of those companies with the magic touch in the mid-to-late 1990s, but those halcyon days were about to come to an end.

While PlayStation carried Sony to new heights, the company's other businesses began snagging. Samsung made a big push into the bustling North American television market, selling competitive sets at considerably lower prices. The 2001 release of Apple's first iPod obliterated the MiniDisc and Discman markets. Familiar names like Canon and Nikon took over the high-end digital camera business. Nokia overtook Sony-Ericsson as the leader in mobile phones until 2007, when Apple released its first iPhone, and everything changed.

The Second Coming Of Sony

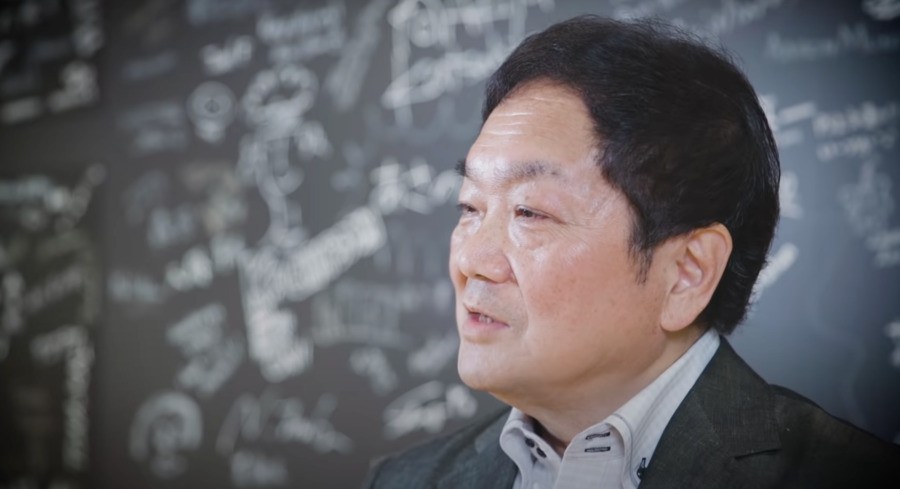

With layoffs, plummeting stock prices, and vanishing markets, the only bright spot on Sony's horizon was PlayStation. By 1998, the game console was well on its way to replacing Walkman as the most successful consumer electronics line in history. This made engineer Ken Kutaragi – who first arrived on the video game scene helping Sony create the audio chip used in the 16-bit Super Nintendo – both a demon and a deliverer around Sony Corporation.

"If you remember back in the 1970s or early 1980s, if you had a cassette player, it may have had a graphic equalizer built into it, little ascending red and green and yellow lines that would show the signal strength as the music volume increased," says Phil Harrison, former vice president, third party relations at Sony Computer Entertainment America. "Ken was the inventor of that. He has the patent for the LED bars rising as the music peaked, and the bar that was on the top would stay on for a while as the sound dropped away so that you could see where the peak got to. That peak level meter LED design was his invention, or co-creation. I think there were a couple of other people involved on the patent as well."

Andy [House] and myself and Kaz Hirai used to joke that you weren't doing well if you weren't fired at least once or twice in your life by Ken and then rehired the next morning

Kutaragi was a brash, temperamental, and outspoken man in a society that taught that "the nail that sticks out gets hammered down." Sure, he was a brilliant, driven engineer, but he didn't fit into Sony's traditional power structure.

PlayStation sales carried Sony through a dry spell, but at the cost of empowering Kutaragi and further infuriating his corporate rivals. Misery loves company; it despises other people's success. Many Sony executives openly despised Kutaragi, describing him as disrespectful, abrasive, and something even more unforgivable in Sony's buttoned-down culture: "untraditional."

"Ken was a, you know ... it wasn't like he was a table-thumping shouter, but he definitely got passionate about things," says Harrison. "I remember one argument with him about something which, to this day, I can't remember the details. It's probably insignificant. His way of finishing the argument was to say, 'Well, if you think that, then you must resign.' It was a very kind of emotional way to say, 'I don't want to have this argument anymore.' Andy [House] and myself and Kaz Hirai used to joke that you weren't doing well if you weren't fired at least once or twice in your life by Ken and then rehired the next morning."

The animosity between Kutaragi and his superiors can be traced back to the early days of the PlayStation project. In the early 1990s, Kutaragi had led the engineering team assigned to co-develop a CD-ROM drive with Nintendo for the Super NES/Super Famicom. Believing that Sony planned to use the unit to open a game division, Nintendo executives quietly abandoned the partnership without telling Sony. Nintendo announced its breakup with Sony and its new partnership with Dutch mega-conglomerate Philips N.V. at the 1993 Consumer Electronics Show, the day after Sony announced it was building the 'Play Station' drive with Nintendo.

Blamed by some executives for having brought shame to the company, Kutaragi approached Sony chairman Norio Ohga for permission to convert his PlayStation disk drive into a stand-alone game console. While the rest of the board argued against it, Ohga gave Kutaragi permission to pursue the project. "There was a meeting with only maybe eight people in it," says Shuji Utsumi, former vice president of product acquisition at Sony Computer Entertainment America. "No other executives. It was just Kutaragi's team pitching Ohga. Ohga was personally interested in the project. And after Ohga saw the whole presentation, he just said, 'Go for it. Do it. This is a project that Sony needs to be in.' He just decided it by himself. No other executives voted, only Ohga. Ohga said, 'do it', and that became a legendary story."

Launching the PlayStation 2

Considering the success of the original PlayStation, Kutaragi could safely say he'd pitched a shutout. With PlayStation 2, he planned to pitch a no-hitter. If everything went as planned, Nintendo and Sega wouldn't even get a single runner on base.

On March 1, 1999, Sony unveiled the PlayStation 2 in a worldwide press conference held in the Tokyo International Forum – a lavish, glass-encased convention centre complete with an enormous opera-house-style meeting hall. Reporters, industry executives, and other invitees flew in from all around the globe to attend the event, which was titled 'A Glimpse of the Future.'

The event began with Sony Computer Entertainment president Teruhisa Tokunaka giving a speech in which he announced the company had shipped its 50 millionth PlayStation. Kutaragi, both the man of the hour and the host of the event, then ran several demonstrations of the 'Emotion Engine' technology that would power the next PlayStation.

The demonstration included video of dozens of balls, faces, and models. By modern standards, the graphics in those demonstrations look primitive, but by 1999 standards, they were groundbreaking. The demonstrations included an image of an old man's face that was considered lifelike at the time. Kutaragi demonstrated his new console's ability to animate dozens of objects and track their motions. Everything looked polished, camouflaging three days of turmoil that had taken place behind the scenes.

"I arrived in Tokyo three days before the event," says Harrison. "I walked into Ken's office, and I said, 'Hey, I just arrived. If you want me to have a look at the slides that you're going to be showing, I'll happily correct the technical information and make sure that there's consistency.' He looked at me, and he went, 'slides? Oh, that would be a good idea.'"

I said, 'Hey, I just arrived. If you want me to have a look at the slides that you're going to be showing, I'll happily correct the technical information and make sure that there's consistency.' He looked at me, and he went, 'slides? Oh, that would be a good idea

Harrison spent the next forty-eight hours working with engineers to create slides with tables comparing the new console's performance against the original PlayStation. They needed to present highly technical information in a way that journalists and consumers would understand.

"By the end of the process, I'm almost hallucinating with jet lag because I've had one hour's sleep in three days," Harrison says. "If you remember, on the stage was a single narrow podium with a VAIO laptop. That was my laptop. I had the presentation on a memory stick. I walked onto the stage about a half an hour before the audience was let in, and my single task ... the only thing I had to do was to copy the latest version of the presentation from the memory stick onto the laptop. Except I did the opposite. I copied the presentation that was on the laptop onto the memory stick. On slide number whatever, there was a typo and a number was given wrong. It was not the end of the world. I was the only one who knew. I just sat with the audience, and I was so tired, and I hoped it went well. It did, but I had that sinking feeling because I knew exactly what I had done. I blame Microsoft Windows for that."

Nobuyuki Idei, who had been appointed CEO earlier that year, gave a speech in which he congratulated himself for having stood by Kutaragi's PlayStation project from the very beginning. In truth, Idei had voted to abandon PlayStation, as had every other executive on the board. Had Idei's predecessor, Norio Ohga, not used his authority to push the project through, Kutaragi would have had to abandon it.

There's nothing new or unusual about a top executive revising history and taking credit for projects they actually opposed; it's fairly standard behaviour, particularly in Japanese corporations with a cultural mandate to respect senior officers. Looking back on 'A Glimpse of the Future,' Harrison observes, "Success has many fathers. Failure is an orphan."

Breaking with tradition, Kutaragi challenged Idei by stating that Ohga had been the only executive who supported the PlayStation. In Japanese corporate culture, contradicting a superior in a public forum is tantamount to a declaration of war. Other executives might have been fired on the spot. Kutaragi, however, could not be sacked easily. His PlayStation division had contributed approximately 40 percent of Sony's profits the year before.

After the main presentation, Kutaragi and Tokunaka held a much smaller press conference in which they answered reporters' questions. Speaking through an interpreter Shawn Layden, who eventually became the chairman of Sony Interactive Entertainment's worldwide studios, they answered questions about technical specifications, launch plans, and upcoming games for over an hour. This was the presentation that would reach the dedicated audience. What reporters and editors from such publications as Famitsu Japan), Game Informer (United States), and Edge (England) took home from this meeting would largely form the public's first impressions of the next-generation PlayStation.

A handful of reporters asked about upcoming games. Kutaragi responded with examples from a seemingly endless list of top publishers. When a reporter from Belgium's Official PlayStation Magazine suggested that the demonstrations might have been rushed, and asked if they would have been more impressive had Sony allowed Kutaragi more time to prepare, Layden fielded the question himself. Sounding surprised, he asked, "You weren't impressed?"

For his part, Kutaragi expressed lofty goals. He talked about recent studies suggesting that playing the piano might stave off the effects of dementia and said he hoped his next-generation PlayStation might do the same.

PlayStation 2 Takes Center Stage

The Japanese launch of PlayStation 2 took place on March 4, 2000.

Game hardware launches had long been big events in Japan. Though the launch of the original Famicom went largely unnoticed, Tokyo ground to a halt with the launch of the Super Famicom on November 21, 1990. Nintendo-mania took Japan by storm. The Yakuza, Japan's organized crime syndicate, reportedly attempted to hijack trucks delivering the game console.

The launch of the original PlayStation, on December 3, 1994, drew crowds, but even larger crowds had turned out two weeks earlier for the November 22 launch of the Sega Saturn. But nothing overshadowed the March 4, 2000, launch of PlayStation 2. It made headline news across the globe.

Despite hardware shortages and a dismal selection of games, the excitement surrounding the PlayStation 2 launch eclipsed that seen with all previous console launches. Huge lines formed in front of electronics stores, particularly in Akihabara, Tokyo's 'Electric Town' retail district.

Because of high demand, most stores had customers reserve their systems weeks in advance, warning them that few consoles would be available on launch day. On March 3, even customers who had reserved systems lined up to make sure they got theirs before inventory ran out. Crowds of people who hadn't preordered turned out as well. Enormous lines formed around the few stores with unassigned PlayStation 2s. Four thousand people lined up in front of a LAOX store. According to the manager, the store had 200 units to sell.

Enormous lines formed around the few stores with unassigned PlayStation 2s. Four thousand people lined up in front of a LAOX store. According to the manager, the store had 200 units to sell

Though they normally opened at 11:00 a.m., at the government's request, all stores selling the PlayStation 2 began handing them out at 7:00 A.M. to avoid a nationwide traffic jam. A short but organized frenzy ensued. Stores sold every available console in a little over an hour's time, and then life went back to normal. By 9:00 A.M., Akihabara was mostly empty. The crowds went home to try out their new PS2s or to mourn not having one.

One week later, Bill Gates officially announced Microsoft's entrance into the video game industry at the Game Developers Conference in San Jose. The rest of the world may have wondered what Microsoft and Nintendo would bring to the market, but in Japan, consumers had already chosen PlayStation 2. The lack of games didn't matter. Spurred on by PlayStation 2's ability to play DVDs, Japan finally embraced movies on discs, knowing that over the next few months, hundreds of games would start trickling out.

The biggest games during the Japanese launch were Ridge Racer V and Dynasty Warriors 2, the sequel to a popular title on the original PlayStation. Game support continued to lag for the first few months. The first bright spot was Namco's Tekken Tag Tournament, which arrived a few weeks after the console's launch. But most of the early releases were unambitious.

Despite the lack of titles, Japanese consumers snatched up every available PS2. Sony couldn't keep up with the demand. With the North American launch scheduled for later that year, the video game industry expected Sony's second wave of dominance to go international.

In the meantime, things weren't going well for Nintendo. Having originally announced plans to launch its next-generation console sometime in 2000, Nintendo grudgingly confirmed rumours that the GameCube was still more than a year from launch. Microsoft was still more than a year away from launching Xbox as well, giving Sony a one-year head start on the competition.

In Japan, Sony relied on movie sales and the promise of great games to come. Japan was loyal to Sony. In the United States, where the terms 'video game' and 'Nintendo' were sometimes used interchangeably, no one knew how loyal PlayStation owners might feel toward the Sony brand. The executive team at SCEA wasn't about to leave anything to chance.

The American Sony

The executives at Sony Computer Entertainment (the Japanese operation) came across as corporate and technical. The team at Sony Computer Entertainment America (SCEA) was more polished and sported a flashier image.

Nearly from the start, SCEA leveraged its roots in the entertainment business. Sony threw the largest and most sought-after parties at the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3). Though he didn't perform, Prince attended Sony's party at the 1996 E3. In 1997, Nintendo made a splash by hiring the B-52s to perform at its E3 party. That buzz was short-lived. Sony's party was an all-out concert with the Foo Fighters onstage.

Behind the scenes, though, SCEA's executive team was filled with buttoned-down professionals, men whom the Japanese team trusted because they'd all worked directly with Ken Kutaragi in one way or another.

After joining SCEA in 1995, Kazuo "Kaz" Hirai had moved steadily up the corporate ladder, being promoted to vice president/COO in 1996, then president/COO in 1999, then president/CEO in 2003. Having attended an American school in Japan before spending three of his teenage years in Toronto, Hirai spoke English without a noticeable accent. He was tall and dapper, and he cut a suave image in an industry that still catered to geeks.

Hirai had the unenviable task of working directly under Kutaragi. Before he took over, the company had gone through a number of top executives, beginning with Worlds of Wonder and Atari veteran Steve Race.

His background is PR, so he understands the ramifications of a bad quote. When he started, he was the PR guy for Kutaragi

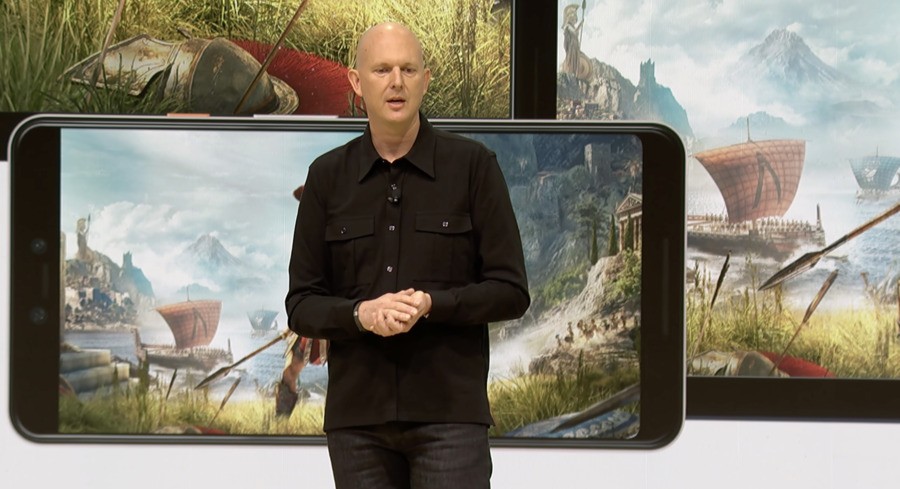

Other executives on the team included Welsh-born, Oxford-educated Andrew House, who had originally moved to Japan to teach English before joining Sony Corporate in 1990. Diminutive in stature, stylish, and unfailingly intelligent, House not only spoke Japanese fluently but also had the rarer skill of being able to read kanji. Having begun his tenure with Sony in international PR, he quickly moved to the PlayStation division, where he learned to work with Kutaragi. House managed SCEA's communications, ensuring that the company maintained a polished image in the press. "Andy's very diplomatic, very measured in what he says," says Rob Dyer, former senior vice president of publisher relations at SCEA. "His background is PR, so he understands the ramifications of a bad quote. When he started, he was the PR guy for Kutaragi."

Then there was British-born Phil Harrison, SCEA's executive VP of third-party relations, research, and development. Unlike House, with his background in language, Harrison had a lengthy pedigree in games, having published his first title as a fourteen-year-old.

Finally, there was SCEA's vice president of sales, Jack Tretton. Born in Boston, Tretton approached his work with an East Coast swagger. Let Hirai, House, and Harrison deal with the press, speaking in polished nuances. Tretton called things precisely as he saw them, with a strident, flamboyant flare. "You knew exactly where you stood with Jack," says Dyer. "Jack was very direct, very honest, very straightforward. He is a very funny guy, and he has a wicked sense of humour."

Compared to other SCEA executives, Tretton was the wild child. He was the executive who came up with the memorable and often combative quotes. In 2006, Wired magazine's Chris Kohler asked Tretton why the PlayStation 3 wasn't backwards compatible. Tretton replied, "I would like my car to fly and make breakfast for me, but that's an unrealistic expectation." In 2007, he told a reporter at Electronic Games Monthly, "If you can find a PS3 in North America that's been on store shelves for more than five minutes. I'll give you 1,200 bucks for it."

You knew exactly where you stood with Jack. Jack was very direct, very honest, very straightforward. He is a very funny guy, and he has a wicked sense of humour

SCEA enjoyed an important advantage over its North American rivals – its parent company allowed its executive team greater latitude. Sega of America, which was fighting a losing battle to keep its Dreamcast hardware alive, took orders from the company's Haneda headquarters. Relations between Nintendo of America (NOA) and its Japanese parent, Nintendo Co. Ltd. (NCL), were even tenser. NCL president and CEO Hiroshi Yamauchi often tormented NOA president Minor Arakawa, who was both his employee and his son-in-law.

As leadership in the Sony Corporation became a slowly revolving door, SCEA became a proving ground for the larger corporation. Both Hirai and House would eventually land jobs in Sony's highest offices. They, in turn, showed confidence in the lieutenants with whom they had worked.

As the PlayStation 2's American release approached, Hirai announced that the launch would take place on October 26 and that SCEA would sell one million consoles. One million units was a huge shipment, but with Christmas approaching and consumer enthusiasm peaking, most industry insiders thought that one million wouldn't meet demand.

Behind the scenes, Harrison, the executive in charge of third-party relations, worked feverishly to make sure the American launch included the aide array of games so clearly missing during the Japanese launch. His job was made harder by a dirty little secret that Sony scrambled to hide from the press: programming games for PlayStation 2 was incredibly difficult. Around the industry, frustrated programmers started joking that the only emotion that the Emotion Engine gave them was "despair." Asked about working with the new console, one American programmer responded, "It's the hardest console to program since the Atari 2600."

"I wouldn't call it easy, but six months of effort and pretty much everybody was making forward progress," says Mark Cerny, a game designer producer who maintained close working ties with Sony. Cerny, who worked on both the Crash Bandicoot and Spyro the Dragon games for the original PlayStation, helped develop a programming engine for the new console.

"The first issue we had was that PlayStation 2, this brand-new hardware, was going to need brand-new technology, and we all wanted to get an early start on it," says Cerny. "Since I could speak Japanese and I'm always willing to travel, I did a sabbatical in Tokyo for three months before dev kits were widely distributed, learning about PlayStation 2 and writing a sample engine. The PS2 let us create free and open 3D worlds. Naughty Dog, with Crash Bandicoot, gave the appearance of this lush 3D world, but, of course, the camera was on rails. While Insomniac was doing Spyro one room over and showing that you could do open-world stuff on the PlayStation 1. The goal shifted to a no-load open world that you could freely traverse. That was quite the target, but it was largely achieved with Jak and Daxter."

Since I could speak Japanese and I'm always willing to travel, I did a sabbatical in Tokyo for three months before dev kits were widely distributed, learning about PlayStation 2 and writing a sample engine

Difficult to program or not, publishers readily gambled on the PlayStation 2's success because of its predecessor. SCEA's polished and aggressive executives gave off the air of a winning team, and their hardware fit the Sony image of success. Game companies both big and small laboured to have their games ready for the U.S. launch.

On September 19, one week before the launch, analyst Rick Doherty called a reporter at MSNBC and said, "I got big news for you. Sony isn't going to launch on time – either that or they're going to market with half the units they promised."

According to Doherty's sources, Sony had shipped 500,000 consoles instead of the promised one million. When approached with the information, SCEA spokesperson Molly Smith told the reporter that she would need to speak with her bosses and that she would get back to him. The next day, Sony announced it would have only 500,000 consoles available for launch and that it would ship an additional 100,000 consoles every week through January 1. "We are one month behind in production," Smith told the press. "Sometimes it's not an exact science."

The consoles would have sold out had Sony shipped twice the promised inventory. Riding on the success of the original PlayStation, PS2 entered the North American market preordained for success. Most stores ran out of inventory on preorders alone. Adding to the excitement was the list of twenty-nine launch titles. EA Sports had SSX, NHL 2001, and Madden NFL 2001 ready on launch day. Namco had both Ridge Racer V and Tekken Tag Tournament on day one. Konami provided an arcade hit called Silent Scope. There were racing games; along with Ridge Racer V, there was Midnight Club and MotoGP. Take-Two Interactive published a billiards simulation for the launch. Agetec, Activision, and THQ had RPGs, something that had been missing from the launch of the original PlayStation.

Just as the retailers had in Japan, American retailers sold out on launch day, and the shipments that followed were largely sold out before reaching shelves. Because of the initial shortages, retailers the world over struggled to meet their presale orders.

Having launched PlayStation 2 in Japan just a week before the end of its fiscal year, Sony shipped 1.4 million consoles in 2000. By the following March, Sony would ship over 9 million worldwide without coming close to meeting demand.

The console would eventually sell over 155 million units, making it the most successful video game console of all time.

This feature is taken from the book THE ULTIMATE HISTORY OF VIDEO GAMES, VOLUME 2: Nintendo, Sony, Microsoft, and the Billion-Dollar Battle to Shape Modern Gaming by Steven L. Kent and is reproduced here with kind permission. Copyright © 2021 by Steven L. Kent. Published by Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Please note that some external links on this page are affiliate links, which means if you click them and make a purchase we may receive a small percentage of the sale. Please read our FTC Disclosure for more information.