Some game developers are drawn towards projects because they represent a challenge, or the chance to work on fresh hardware. Others may feel attracted to contributing to the development of a particular game because of its subject matter or the concept upon which it is based. Doug Lanford has experienced all of these factors, and furthermore he found them all in a single project.

"I completed my Electrical Engineering degree in 1991, and then moved to the San Francisco Bay Area where I ended up getting a job as a game tester for Sega of America," Lanford explains. "A few months later Sega was building their first internal development studio — the Sega Multimedia Studio — and discovered me already working there. I spent four years at Sega, working on two Sega CD games: Jurassic Park and Wild Woody. As I was finishing Wild Woody, several of my co-workers left Sega and joined GameTek to start working on Robotech. Six months later, they offered me a job at GameTek, since they needed another programmer, as well as a dedicated fan of Robotech to help steer the design...how could I refuse?"

Lanford's love of the classic anime series — which is in fact a mash-up of Japanese shows Super Dimension Fortress Macross, Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross and Genesis Climber MOSPEADA — led him to assume a role on the project which went way beyond just programming. "Primarily I was the junior of two software engineers on the project," he explains. "However, we all wore multiple hats on the project, so I also served as one of the story writers and game designers. When I arrived at GameTek, they had been working on the title for about a year, but very little work had been done on the game itself. Most of the work up to that point had been on getting the beginnings of a game engine working that could display things on screen and so on. There was no 'gameplay' at that point. Robotech Academy — which is what the game was known as when I came on board — consisted of a three or four page high-level design document that GameTek had thrown together a year before to help get the Robotech license. The idea of it was that the entire game would take place before the events of the cartoon, and all of the action would be in simulators as you train at the Robotech Academy as a cadet. It didn't have much story or excitement to it. When they asked my opinion, I threw it out and started from scratch."

GameTek was happy for Lanford to steer the project, but the company did place some restrictions in his path. "It had to be based on the Macross-era ships, as GameTek wanted to market the game in Japan as well, and had to have the Zentraedi as the main enemy," he says. "The game would include a new enemy in the form of a bunch of easy-to-render crystals. The crystals were there because at the time we did not know if the final N64 hardware would be powerful enough to display a bunch of more complex ships on screen at the same time, but we could show dozens of crystals. They had already been named 'Ebolians', which stuck." The name of this new enemy would also be reflected in the game's proposed title: Robotech: Crystal Dreams.

Lanford's knowledge of the original TV series stood him in good stead, as he was able to skilfully position the game so it made sense within the canon of the show. "I came up with the idea of a new war between the end of the Macross portion of the show and the beginning of the Robotech II: The Sentinels movie, against a lost fleet of Zentraedi allied with this new crystal intelligence. From there Ian Harac and I fleshed out and wrote the game story and dialogue."

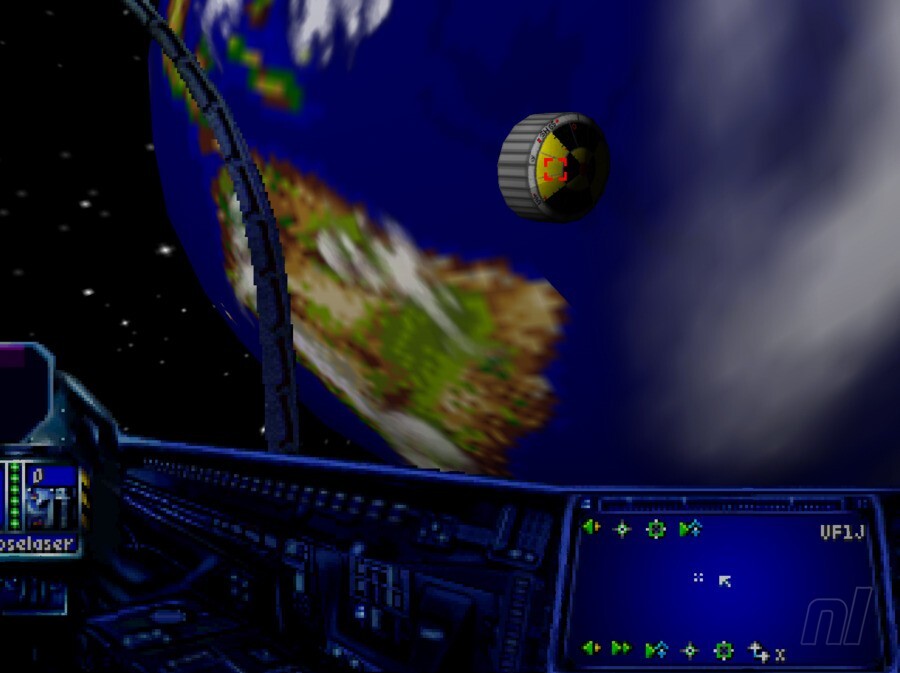

While Lanford and the team at GameTek wanted to make sure the game would stay true to the original Robotech storyline, they had high aspirations for the gameplay as well. "We were building a space combat simulator similar in style to PC-based games like X-Wing, Tie-Fighter and Wing Commander," he explains. "Another interesting thing about the game was we were building it with a totally open world — what is often now called a 'sandbox' game. The player would have been able to fly anywhere he wanted, and his actions through the game would affect his reputation with the various characters he interacted with. For example, if you joined a convoy but then abandoned it in the middle of an attack, your reputation with the defence forces would take a hit."

However, Lanford is keen to stress that there was some kind of structure in place, as well. "The game did have a number of pre-built missions that drove the game story," he states. "We also planned a robust random mission generator as well. As the player completed missions they would gain credit at various shops which they could use to purchase fuel, ammo, and upgrades for their Veritech fighter." From a technical perspective, the sights were set high. "Everything in the game was to scale," Lanford says. "The Earth and Moon were their correct size and distance from each other, and you could fly right up next to Zentraedi capital ships which were four miles in length."

When Lanford joined the project, it was already being hyped as a key release for Nintendo's N64 system, which had at this point still not seen release. GameTek was recruited as one of Nintendo's decidedly-uninspiring "Dream Team" members, lending the project even more importance. As Lanford reveals, GameTek did a good job of inflating expectations prior to his arrival at the company. "Before I joined, GameTek had cobbled together some pre-rendered example shots that a lot of people believed were from the actual game, but actually were not," he reveals. "After I joined, most of the screenshots were from the actual game — including the pilot's reflection in the cockpit window. I had a fun time building that into the game, along with the character facial animation to lip-sync the recorded vocals."

It is these lush screens which fuelled a second wave of anticipation for the title; shots appeared in magazines all over the world and Robotech: Crystal Dreams slowly crept up the list of "must have" titles for the N64. However, even though consumer and press interest was growing, Lanford admits that there was a feeling within GameTek that the company had bitten off more than it could chew. "We definitely had our rough patches," he says. "One big problem was that GameTek was a small company that up to that point had mostly been a publisher of small-scale games. We were its first internal development group, and we were attempting to build a very ambitious game with a crew less than half the size it should have been. We also got caught in the trap of building a great game engine rather than working on a game. There always seemed to be some new fun feature someone would come up with — like the aforementioned pilot reflection, which was nifty but not required to play the game — and we never seemed to be putting it all together into a game."

Things took a turn for the worse in 1997, as GameTek filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The troubled company managed to remain active, thanks largely to a publishing deal with Take 2 Interactive which brought in some much-needed cash, but for Robotech: Crystal Dreams the writing was on the wall. The game was a costly venture for the firm and there were serious doubts about whether or not it had the funds to continue development. An unlikely saviour came in the form of Capcom, which stated that it intended to publish the finished game. A similar deal was already in place for the Japanese market, but with Tomy handling distribution. "I believe the plan was for Tomy to distribute the game in Japan — as a Macross title with a few dialogue and story changes — and for Capcom to distribute it everywhere else," recalls Lanford. "However, neither seemed interested in pulling GameTek out of the fire or helping to complete the game." Because Tomy and Capcom wouldn't commit themselves to bankrolling development, the project was left in a decidedly grim position.

Despite GameTek's dire situation, Lanford admits that he was so focused on getting Robotech: Crystal Dreams finished that he was largely unaware of the problems facing the firm. "I didn't realize GameTek was in trouble until the day I showed up at work and was told people would be leading us individually to our desks to collect our belongings," he recalls. "I had an idea things were a little rough for a month or so before that, but didn't think GameTek was on the edge of closing its doors. The sad thing was that we had just finally got to a point that we were starting to see what the actual gameplay might be like. I had cobbled together some preliminary gameplay functionality so we could demo the game in the Capcom booth at the 1998 E3 Trade Show, and it was fun to fly around, target enemy ships and blast them to pieces. At a guess, we probably had another nine months or so of development to complete the game." Lanford and his team would sadly never get the chance.

Following GameTek's collapse, Take 2 Interactive acquired the company's assets but Robotech: Crystal Dreams was effectively abandoned. Lanford still has no idea why such a promising and high-profile title — with less than a year's development remaining — wasn't finished or at least offered to another publisher. "I've never gotten a good answer to that question," he says. "Over the next five or six months after GameTek died, I personally visited several companies to demo the game, but nobody ever bought the rights to finish it." Despite this, Robotech: Crystal Dreams still attracts a lot of attention, even today — and not just from hardcore fans of the anime series. "It is fun to know that it still lives a bit out there," Lanford says. "We really hoped to add our own little chapter to the Robotech saga with the game, so knowing people are still interested is gratifying."

This article was originally published by nintendolife.com on Sat 5th October, 2013.

Comments 23

What we REALLY need is a sequel to Gotcha Force, THATS a good robot game !

Sadly, it belongs to capcom, former super developer gone rogue.

The video looked cool. I'd LOVE to have a Robotech game or two. I especially like the space flight simulation in this one. Wish they made more games like that. Kind of like Colony Wars. While i love Star Fox, it wasn't enough for me.

@Einherjar YES! We need another Gotcha Force!!!

There are roms for it out there. I imagine what was being shown off to prospective buyers to fund the game. I really wanted this gamre BAD. ROBOTECH on the GCN was okay, but this looked amazing.

This game looks like it would've been great had it not been for bankruptcy. Very ambitious game for it's time.

I remember hearing about this game. It's such a shame it never went through, but I guess there's always Freespace...

I remember reading about this game in a gaming magazine (remember those?) after the N64 came out... and then never hearing about it again until now.

I want a remake of Battlecry

I played the prototype on the computer and the pilot reflection was a cool idea. Gameplay reminded me of Star Wars Arcade for the 32X.

I am a huge Robotech fan (Moreso than Macross, really), and remember vividly the trials and tribulations of "Crystal Dreams" among the Robotech community in the late 90's. There were always little tidbits of news and developments here and there, but the game seemed like it was taking forever to get developed. It never got off the ground, and the Robotech community itself slowly lost hope in it altogether.

But, yes, I remember the scope that Gametek (at the time, makers of "Wheel of Fortune" and "Jeopardy") wanted to take on it. It was going to be a universe much larger than anyone had ever seen at the time, and, even then, I thought it was more than any developer would be willing to chew. Also, it was on the N64, which was already a distant 2nd place in the console wars.

Sounds like a pretty standard reason for a project to go under. They had no aim. It's okay, while the concept of it sounds very cool I really doubt it could have lived up to any of that potential. Those old consoles were so primitive anyway, it just would not have looked very good. If this developer still doesn't understand why the project was never finished I hope to God he isn't a lead on anything today.

Remember picking up a GameFan magazine with "screenshots" of Robotech: Crystal Dreams for Ultra 64: Remember these?

http://i.imgur.com/79VfVfj.jpg

So many people including myself fell for the hype.

Not only were those visuals not impossible on any PC 3D card or arcade board, let alone on the slim resources Nintendo 64 offered--It was also not possible on the much more powerful and expensive workstations & visual systems that Silicon Graphics had. Not at real-time framerates. Anything from SGI back then would have had to spend time rendering those images offline. In other words, obviously it was prerendered CG.

That said, it is a shame GameTek could not get the additional funding & development staff to redesign the game for the then-upcoming Project Dolphin (GameCube). With dozens of times more power/performance than N64, more & faster memory, a reasonably impressive game based on their ambition could've been achieved.

Ah well...

Indeed it always seemed way too ambitious for a company like GameTek, who was mostly known for making game-show adaptations.

Loved Robotech. Any chance for this to become a Kickstarter project?

@Einherjar No what we really need is Sega to let Nintendo make a chromehounds game. It's still the most fun I have had on Xbox live (before they shut the servers). It's not many robot games that let you fit a 1200mm howitzer to a mech straight through the legs (admittedly with a little bit of fiddling the build) just so you have the mother of all money shots!

@ICHIkatakuri Dont ask Sega for that, ask "From Software", the makers of the Armored Core series Sega just published this one. Although i would love an Armored Core game on the WiiU simply to see how overboard they could go with the gamepad. Maybe have some dials and switches to tune your mech on the go via the gamepad

Nah, From Software are good and I like armored core but prefer the job they did on chromehounds and though SEGA were publishers they hired from to make the game and retain the IP. It's a SEGA game and needs their blessing

I remember reading about this game for months and months on Nintendo Power. I was incredibly bummed w hw n I found out it was cancelled.

I enjoyed the robotech game on the cube n wondered why they didnt make it a franchise

I played only battlecry on the ps2... That was fun! This sounds like it would have been awesome at the time of development! Damn shame...

I remember being sooooo excited for this game. I was a really big Robotech fan (more than Macross) and as soon as I read about it in a gaming magazine, I re-read all of the Jack McKinney books in anticipation.

I really liked Battlecry though. That was a great game.

I was a big fan of Robotech and Macross back in the day. I remember reading about this game and being really excited for it. I kept waiting and waiting but it never came out. There was also a PS1 Macross game that was supposed to get a Western release. A demo made it onto one of the OPM demo discs. I played that demo over and over and kept waiting for the game to come out. It never did - but I kept that demo disc for many years. Eventually we got Battlecry.

Huh, I must have missed this article when it first came out. Anyhoo, it was an interesting read. I was really hyped up for this game back in the day and was very sad when it was canned.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...