We're big fans of pen-and-paper fantasy role-playing games here at Time Extension. In fact, we were the first to pour out a little liquor when the legendary Gary Gygax passed away. The reason for our love comes not from every human's natural attraction to multiple-sided dice, but because of the sterling retro gaming fare derived from them. Dungeons & Dragons has inspired several brilliant video games, and even the worryingly nerdy Warhammer tabletop universe has led to some praiseworthy tactical RPG shenanigans. The lesser-known Shadowrun is another prime example, although it has been the recipient of less attention than it deserves over the years.

As an actual dice-led affair, Shadowrun is an incredibly well-respected game that has been around for thirty years. Created by legendary role-playing publishers FASA Corporation in 1989, this cyberpunk caper is now in its sixth incarnation. We won't attempt to explain how to play Shadowrun in this form, but we can tell you that the rules of the game have been recognised by the power players in the role-play fraternity, and it scooped a prestigious ENnie Award back in 2006.

The Shadowrun universe is a fascinating one, set in a world some 50 years in the future. Humanity is beginning to embrace new and unfamiliar technologies such as cyberspace and the melding together of man and machine; giant mega-corporations rule, and vampire viruses mutate people into bloodthirsty abominations. Meanwhile, some unexplained occurrence has brought the use of magic into the world, meaning that society is now overwhelmed by all manner of different creatures and races. The perfect setting for an RPG video game, then.

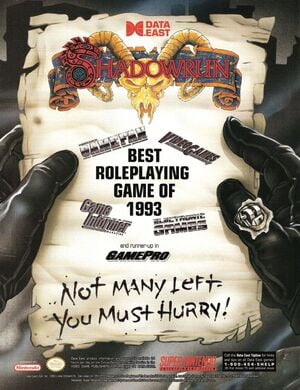

Back in 1993, most of the RPG titles for the SNES were either sub-par conversions of home computer titles or NTSC-only Japanese crackers from the likes of Square and Enix, many of which never received the localisation treatment they were so obviously worthy of. Shadowrun — coded by Australian studio Beam Software -– bucked the trend, garnering a host of glowing reviews at the time of release.

They were just about to start the Lord of the Rings games, and were in a panic about the text needed... I ended up as one of the first full-time game designers in the world, working for Melbourne's video game subsidiary Beam Software

Shadowrun features video game RPG staples such as turn-based combat, magic, collecting items and earning money, but also boasts neat mini-game elements like entering cyberspace to hack into computer terminals. The whole she-bang is tied up with some cracking music, gritty, isometric graphics and a sense of dread and foreboding that permeates every scene that you are in. Loosely based upon FASA bod and Shadowrun co-creator Robert N. Charette's Shadowrun novel Never Deal with a Dragon, this is a SNES classic that we cannot recommend enough.

One of the key personnel behind this classic title is Pauli Kidd, who recalls all too vividly the tumultuous events that surrounded the production of the game. The development process was almost as chaotic as the world it was attempting to create.

Kidd is something of a video gaming veteran. "I was there in the really early days,” she reveals. “You know — when computers were mostly made up of valves and bear fat. Just after leaving university, determined to be a writer, I was enjoying the balmy lifestyle of being a charge upon the state — when lo and behold, my girlfriend found an advert in the paper looking for writers. It was Melbourne House, looking for people to create games for them. They had just done Horace Goes Skiing. I came in and freelanced some game designs for them. They were just about to start the Lord of the Rings games, and were in a panic about the text needed. So they hired me full-time to ‘do word stuff’. I ended up as one of the first full-time game designers in the world, working for Melbourne's video game subsidiary Beam Software."

Kidd was familiar with the Shadowrun licence, something which clearly helped her on her way: "As a rabid role player, I knew it pretty well. I was selling my own RPGs at the time, and I knew the designers from conventions over in the USA. So I knew what would please them and what might piss them off. As a fellow RPG game designer, I wanted to do something that they would like. I have to say, the idea of splicing fantasy with cyberpunk was one that I thought damned silly. I'm not sure the 'paper'' RPG was one I would play by choice, but dammit man — we're role players! Open the damned Coke, and pass me that D20!"

As great as the final game was, it was not plain sailing down at Beam. Greg Barnett, one of the prime movers in getting the game off the ground, left midway through the development process, and Kidd gives a grim recollection of this dark time: "Barnett had done an initial concept idea, but then he left the company. Sometime later, when the game surfaced from the nightmarish deeps, I was brought in to be producer and designer. Sounds innocent enough, but there was a layer of evil to all of this. The company had promised the publisher that the game would be delivered by a set deadline. Contracts were already signed and sealed. The game was then promptly forgotten about."

It didn't remain forgotten forever, though. "Normally, a year was allotted to the making of a game," continues Kidd. "The company shelved Shadowrun, and only unearthed it about five and a half months before the deadline. This gave them a problem: how to save face when they failed to meet their deadline? Their inspired idea was to take a game designer who had been rocking the boat over employee rights and other issues, and suddenly 'promote' them to producer — then give them the game. When the deadline failed, blame it on the producer, and sack them as a face-saving exercise. Much to their annoyance, we got the game done by deadline. This was done mostly by ignoring the usual morass of company BS — the constant meetings, updates, workshops and 'progress sessions' they usually did.”

It's clear that all was not well at Beam Software during the time of Shadowrun's development, and Kidd is more than happy to elaborate further on the troubles she and her team faced. "It was a little like a cross between Apocalypse Now and 1984,” she comments. “Beam Software was a madhouse, a cesspit of bad karma and evil vibes. The war was reaching shooting level; old school creators who just wanted to make good games were being crushed down by a wave of managerial bull. It was no longer a 'creative partnership' in any way; it was 'us' and 'them'. People were feeling creatively and emotionally divorced from their projects."