One of the first PlayStation titles to really show off the raw 3D muscle of the system, WipEout was created by a team of around ten people and took approximately fourteen months to complete, with the bulk of that time being spent exploring untested and unknown prototype hardware. A ground-breaking technical achievement, it was equally famous for the fact that it managed to seamlessly incorporate music from professional dance artists, something which games had been trying to do for years - with varying degrees of success. It’s perhaps this element of the game that sticks in the mind of people who experienced it for the first time back in 1995.

We were really into the kind of music when we developed the game, so it made sense to feature it in some capacity

The game’s designer was Nick Burcombe, who started his illustrious career in 1989 at Psygnosis - the UK company which would eventually be swallowed up by Sony Europe to create the now-defunct Studio Liverpool. He reveals that the use of music in the game wasn’t for marketing purposes, but was primarily to accentuate and intensify the experience. “It wasn’t a commercial decision, but a purely artistic one,” he insists. “We were really into the kind of music when we developed the game, so it made sense to feature it in some capacity. The choice to combine WipEout’s excessive speed with techno an organic one; it just felt natural. Sony’s marketing department made good use of it afterwards, deftly positioning WipEout as part of a new generation of cool games.”

Burcombe’s memory is so sharp that he can even pinpoint the exact moment when the decision to use techno music occurred. “I was playing the last race of the 150cc cup in Super Mario Kart on the Super Nintendo, and I’d muted the game audio so I could hear my own music,” he explains. “Age of Love was playing on the stereo in the background. I’d tried about ten times to beat the last race, and on this final attempt, I was in second place by the time the music was about 2:10 mark. The final laps took place where the track was at 2:45 and it felt so exhilarating; it was as if the music was pushing me on into a deeper gameplay experience. I made it across the line with about a tenth of a second between me and Bowser, who was pushed into second place. Psygnosis artist Digby Rogers was in the room at the time, and he was literally on the edge of his seat by the end of the race; he commented that it was the most amazing thing he’d ever watched on TV! That’s ultimately where the concept of marrying the thrill of racing with the intensity of techno came from.”

The Genesis of WipEout

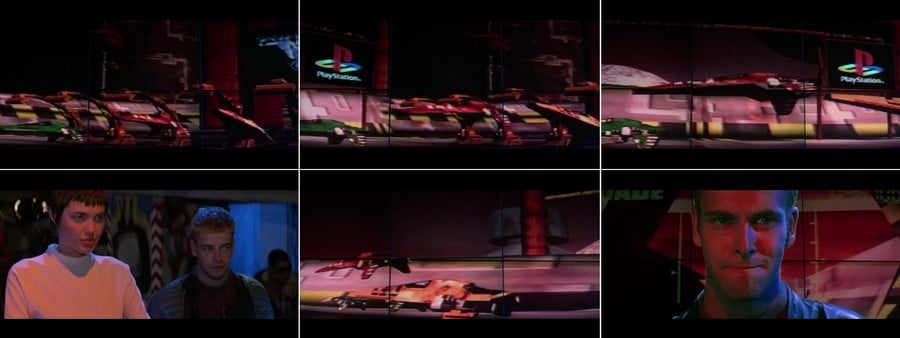

The next step for WipEout was a pre-rendered CGI sequence created by Jim Bowers (who based the ships on designs he had previously created for the Amiga and Atari ST title Matrix Marauders) set to music by popular UK dance act The Prodigy. This allowed Burcombe to solidify his ideas for the game even further and resulted in the concept getting some unlikely exposure via Hollywood.

“Jim’s original dogfighting chase scene was used to gain support for the game, and it worked - people just seemed to get it,” Burcombe says. “Much later on, Jim approached us with the opportunity to expand the sequence for a scene in the movie Hackers, which was in production around the same time and starred Angelina Jolie and Jonny Lee Miller. I used this opportunity to clarify further some of the gameplay mechanics and rules for WipEout.”

While WipEout’s celebrated soundtrack - which showcased the talents of Orbital, Leftfield and Chemical Brothers, as well as songs from legendary in-house Psygnosis music producer Tim “CoLD SToRAGE” Wright, who we’ll get onto shortly - would go on to gain critical acclaim, Burcombe’s original playlist reads like a who’s who of early ‘90s techno acts - many of which will be totally unknown to anyone over the age of 30. The full list, which has never been published until now, included:

- Cygnus X – Orange Theme

- F.U.S.E – Substance Abuse

- Tomas Heckman – Amphetamine

- Dave Clarke - Red 2

- CJ Bolland – Horsepower

- Pump Panel – Ego Acid

- Prodigy - No Good

- F.U.S.E – F.U.

Although the musicians of today are all too happy to sign lucrative licensing deals so their songs can be featured in video games, back in the early ‘90s the situation was very different. “The idea of a proper recording artist allowing their work to be featured in a video game was almost laughable,” explains Burcombe. “Because of this, it was harder than you might imagine to get people on board. However, bands like Orbital - who were and still are very forward-thinking - could see the link and were incredibly keen to be involved.”

The idea of a proper recording artist allowing their work to be featured in a video game was almost laughable

Because Psygnosis could only secure three tracks from professional artists for the original WipEout, the aforementioned Tim Wright had to step up to the plate and compose a selection of songs for the game, all the while sticking to the main theme dictated by Burcombe’s own musical tastes. His aural contribution to the title cannot be understated; outside of the trio of licenced songs, the entire soundtrack of WipEout is down to Wright.

“When I was first asked to write the music, I saw it as just as another game to work on, to be honest,” he explains. “I'd just finished working on another PSone game called Krazy Ivan, which called for Industrial Techno tracks, so I was kinda in the right electronic ballpark - or so I thought. Then I was shown the short movie-style clip that Jim Bowers had been working on, a version of which would later be included in the film Hackers. That changed my mind, and inspired me to think that this game could be something quite special, something different.”

Working on the game would prove to be more difficult than Wright suspected and required him to change his usual style. “I remember playing the first track I'd composed to Nick,” he recalls. “He said something like, ‘yeah, it's a decent track, but it's a bit too industrial, too old-school electronic. We need something faster-paced and more clubby’. Clubby? I didn't have a clue. I really didn't care for dance music at all at that stage. I was a child of the '80s, so it was going to be a bit of a struggle. Around that time, Psygnosis was moved from the Liverpool Docks to new shiny offices constructed from metal and green-tinted glass. I reasoned that a new futuristic environment might encourage me to create new futuristic sounds, so I sat down in my brand new studio, armed with Time & Space Volume 1 & 2, an Amiga A1200, a Roland JD800 and an AKAI S2800 sampler, and I started to knock some ideas around.”

All of the songs were composed within a very short time frame whilst consuming copious amounts of Red Bull and takeaway pizza

Wright has always believed that the musical direction he took on the first WipEout was largely influenced by the samples he was working with, but a recent discovery has made him reconsider his recollection of events.

“Around the time I was writing the WipEout tracks my brother Alistair - totally coincidentally - gave me a cassette tape labelled ‘Goa Trance’," he says. "I'd listened to that tape a few times in the car and then basically forgotten about it. I found the tape again a few days ago and popped it into my old Sony Walkman cassette player and pressed play. I was greeted with track after track of CoLD SToRAGE/WipEout-eqsue music. I was gob-smacked; I'd never really heard any other music that was that similar in style to my original WipEout music, but maybe that tape had inspired me in some way? I'm not sure who the composers are, and I've tried using Shazam and other services to identify the tracks, but without success.”

Musical Magic

Regardless of where Wright’s inspiration came from back in the middle of the 1990s, the indisputable fact is that he crafted some of the most memorable tunes of the period. “All of the songs were composed within a very short time frame whilst consuming copious amounts of Red Bull and takeaway pizza,” he admits with a chuckle. “I have really fond memories of working on those songs into the small hours and watching the sunrise over Liverpool as I pumped the tracks out into an empty building.”

Somewhat ironically, Wright’s masterpieces came at time when games like WipEout were looking to mainstream musicians to provide their soundtrack, as opposed to video game composers like Wright himself. It’s a testament to the quality of his work that despite the eventual influx of new artists on the sequel, WipEout 2097, Wright’s compositions continued to rub shoulders with the output of 'proper' commercial acts. “By that point, it was easy to coax big-name acts on board,” he continues. “So personally speaking, to get my music on the games at this stage was a massive vote of confidence.”

However, while the musical side of WipEout was progressing nicely, Burcombe and his team had other issues - the most pressing of which was the primitive nature of Sony’s new development hardware. “It was a bit of a nightmare coding for the system at that time, as it was still in the very early stages of development,” he explains. “We had one of the earliest prototype PlayStation dev kits in the UK - it was about the size of a photocopier and was festooned with noisy fans which attempted to keep it cool during use. When a game was running the sound this thing created was almost unbearable - it was like a jet engine! Amazingly, it was only running at a third of the eventual speed of the production console, a fact which created further problems because it’s very hard to code a game when you don’t fully understand what the hardware is capable of. We were almost coding blind, to a certain degree, but the team pulled it off.”

We had one of the earliest prototype PlayStation dev kits in the UK - it was about the size of a photocopier and was festooned with noisy fans which attempted to keep it cool during use

Burcombe’s role as lead designer meant that he didn’t have to get his hands too dirty with actually coding the game, but he could tell that it was a real struggle for his team. “Limited experience, primitive design documents and processes and unfinished dev hardware combined to make the production process a real challenge,” he comments.

“I saw several months go by with not much progress, and at one point we even showed it to Sony Computer Entertainment CEO Ken Kutaragi, and he told us we’d never get it completed in time for the launch of the PlayStation. I think the original goal was to keep it at 60hz in a higher resolution, interlaced. After it became clear that we simply couldn’t achieve that, we lowered our technical sights a little and went for the standard PAL resolution and 30hz. Lots of work went into discovering how to do stuff like building a 3D pipeline and what best practices were. When I sit here now and consider the complexities and challenges of development, it’s amazing that we even managed to produce the game at all. It was truly bleeding-edge stuff.”

Given that the game was breaking new ground in the 3D racing arena, WipEout unsurprisingly called for some rather unique design methods. “Each of the circuits was drawn by myself on large sheets of A3 paper with details and annotations about the elevation and curvature of the tracks,” Burcombe recalls.

“For some tracks, there would be notes at the side describing what the player should able to see or what was hidden from their view. Each track ended up with a distinct feel, which is partly down to the fact that they were rendered by different artists, working independently of one another. Some of the ideas we had couldn’t be met by the hardware, though. For example, the first drop on Altima VII was supposed to be like base jumping off a cliff, and would have required serious skill on behalf of the player to land the ship successfully and maintain speed. In the end, we simply couldn’t draw the track that far so we were forced to include a cave to mask this fact, and then it transpired that we couldn’t drop off the geometry and still keep on top of the relative race positions of each ship, so the top of the mountain and the base of the mountain had to be joined. The end result didn’t quite capture the amazing free-falling sensation I was after when I conceptualised that part of the track, but it still worked. It was a shame, but just one of those things you encounter when you’re developing on brand-new hardware.”

"The mechanics of Super Mario Kart were virtually flawless, so it was a constant source of inspiration for me" - Nick Burcombe

Having already provided inspiration for the game in one sense, Nintendo’s seminal Super Mario Kart would go on to influence another key part of the WipEout experience: its weapons. “The mechanics of Super Mario Kart were virtually flawless, so it was a constant source of inspiration for me,” says Burcombe.

“But we obviously couldn’t have banana skins and shells - we had to make it all futuristic and introduce things like electro-bolts and all that kind of sci-fi stuff. In WipEout 2097, Chris Roberts - who also worked on the PS Vita instalment WipEout 2048 – put in the famous ‘Quake’ effect, and that was just mind-blowing; everybody who saw it instantly fell in love with it, and it went on to become one of the fundamental weapons of the entire series. I’ve heard some people question the inclusion of weapons in the game and the series as a whole, but I can say now hand on heart that we always intended WipEout to be a combat racer. There was never any question of it being purely about speed; we wanted to replicate the same amazing feeling of blasting someone to steal P1 that we'd enjoyed so much in Mario Kart.”

Hardcore Gamers Only

While those who moan about the weapons are clearly misguided, there were other genuine complaints levelled at the game; when compared to later instalments in the series, the original WipEout is surprisingly difficult. “We didn’t really set out with the aim to make it challenging, but we kind of set the difficulty for ourselves – which was probably meant it was a bit too hardcore,” admits Burcombe. “The people on the team that were really good at it fell in love with the demands of the experience, and consequently everyone else got left behind, which is probably why it’s always been a bit of a cult hit with really skilled and dedicated players."

However, one element which contributed directly to the challenge was the unforgiving collision system. “There were no glancing scrapes which resulted in a minor drop in pace in the first WipEout,” explains Burcombe. “You’d just stop dead as soon as you bumped into something. That wasn't by design, it was down to my limited experience that we allowed it to ship like that. It was the first thing that was solved in WipEout 2097, and as a result, I feel that game plays much better, and it consequently scored higher in reviews.”

While the sequel was able to fix this one problem, Burcombe doesn’t feel it bested its predecessor in every regard. “I don’t think some of 2097’s circuits were anywhere near as good as those in the first game; aside from insanely brutal Silverstream track - we probably went a bit too far with that one - the courses from the first game are generally superior. However, that's a reflection of the amount of time we spent designing them as opposed to a lack of effort; all of the courses in the sequel were conceived, designed and rendered in just three months, whereas in the original WipEout we were able to devote about two months to each.”