For Worms creator Andy Davidson, his love of gaming started when he would play his Atari 2600 and Nintendo Game & Watch. It wasn’t long until he received his first computer, a Commodore 64, which led to a passion for developing his own games.

“It’s in my blood,” Davidson tells us. “Video games were the first things that captured my imagination as a kid. Just being able to make something move around on a television screen seemed like magic, and I knew as soon as I saw my first computer, aged nine, in the classroom at school, I wanted to make a game.”

He began developing a new game after getting inspiration from his favourite genre. “I’d always loved artillery games since the 8-bit days,” Davidson explains. “These were where two tanks on each side of the screen had to destroy each other considering angle and power. In 1990, during A-Level maths, I challenged one of my friends to see who could make the best game on our Casio graph-plotting calculators. This was more interesting than schoolwork and the one thing that really interested me was generating random landscapes, and I wanted to explore that further.”

By this time, Davidson had moved to programming on an Amiga, and he quickly realised it was a powerful tool to make more than just a simple artillery title. “The Amiga allowed me to do a lot more with the game than the little calculator did,” he tells us. “One of the first things was allowing the tanks to move. This was a new thing for artillery games, which were normally very static, and it instantly became apparent that this was opening a lot more options in the game. Suddenly you could move about, having to work out the new angle and power made the game a lot more interesting. The game just continued to evolve from there, with things like the introduction of a much larger playing area, and water for an instant kill.”

Around the time, Lemmings was released and playing it gave Davidson an idea. “I was impressed by how small but well-animated the characters were. I’d written a programme called Jack, which was a graphics, sound and music ripper. A friend asked if it could get the graphics out of Lemmings using my programme. To my surprise, it could, and for a laugh, I replaced the tanks in my game with lemmings. This was a 'eureka' moment. The game became a lot more appealing, and there was potential to do more like the way Lemmings lets you choose the different types of lemmings to control.”

Davidson, still in school, continued working on his game, creating deeper strategy and gameplay mechanics. “I wanted to create a game that would be different every time you play, one that my friends could play at school and wouldn’t get boring. The result was the game getting banned from school because people were skipping lessons to come and play it. Once it was banned, I thought I must be onto something, as things that are banned are usually good!”

Following this initial success, he decided to put off going to university and committed himself to getting his game published. “I started working in a local computer shop and it was around this time I saw Amiga Format running a competition about a new language on the Amiga called Blitz Basic 2. The competition was to make a game using it, so I thought this was the ideal opportunity to get my game noticed. I picked worms as the new protagonists and started work on a complete rewrite under the name Total Wormage.”

Davidson had to put a lot of work into porting his game to the new language as well as designing the new worm characters. “The next few months were spent working round the clock on it, staying up all night drawing worms and programming, then getting customers in the shop playtesting it. After entering it into the competition I heard nothing until I saw the results in the magazine. Total Wormage wasn’t mentioned at all. I was gutted. The winner was a clone of an old Atari game called Circus.”

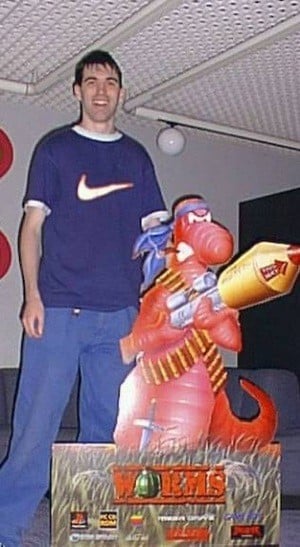

Although he was disappointed not to win, Davidson didn’t give up just yet. “It was then I had the idea of going to an upcoming trade show in London and showing the game to people myself. I put a hastily printed sign up on the door of the shop, closed it for the day, and got the train to London. The game was about 80% done at this point. Team17 was the company I had in mind to show it to because I saw the game as an Amiga game through and through. So, I walked up to their stand with a couple of floppy disks in hand and asked if they still looked at games.”

Team17 co-founder Martyn Brown was manning its stall that day and agreed to look at Davidson's game. “I started loading it up on one of their Amigas. As it was loading, I told them they wouldn’t like it, as it’s a bit weird! But Martyn did like it and asked if I wanted it published straight away. I was convinced this was a wind-up though, it was only the next week when I went to their offices that I believed they were serious.”

Davidson couldn’t believe what was happening and soon realised his childhood dreams might be becoming a reality. “It was all mind-blowing, I was on the way to achieving my dream of seeing my game on the shelf. There were worries as well; I was worried about losing control of it as there were still things left to add, but Team17 gave me complete freedom. I’d finish the Amiga version while they did the ports to other platforms.”

Davidson suddenly found himself working for a major games company. “It was great to meet so many talented people in so many areas, from programmers to artists and musicians," he recalls. "They had a real passion for what they were doing, and that just fed my own passion. I remember showing them the game for the first time and seeing it being played on every screen in Team17’s HQ in Wakefield. That made my day, here was my little game being played by all these people who make games for a living and whose games I’d read about and played.”

For all the excitement, Davidson still needed to get his head down and finish what was now known as Worms. “The Amiga version was nearly done, but we took a year porting it to other platforms while I finished it up. Being at Team17 meant other artists and musicians could get involved, we added new background graphics and music which I couldn’t have done myself. I still wanted to keep my friends involved in the game’s development, as they’d been playing it since the beginning. I valued their opinions as well as Team17’s, who were new to it. I got into a bit of trouble during this time for adding things to the Amiga version while the ports were being done. Things such as the exploding sheep, banana bomb and custom levels went in quite late – but I simply had to have them in the game.”

By 1995, Worms was ready to be released and went on to be a huge hit for Davidson and Team17. “I hoped it would do well but had no idea it would be as big as it was," he explains. “To me, it was still the little game I made for me and my mates to play instead of doing schoolwork. Seeing it on the shelf in the shops for the first time, and later going to the top of the charts, was an amazing feeling. I’d achieved my dream.”

In 1996, a Worms expansion pack was released, which added a single-player campaign and custom levels. But Davidson wasn’t finished perfecting his debut game. The following year, he revisited Worms to develop the definitive Amiga version called The Directors Cut.

“Giving the Amiga the best version of Worms was very important to me, as without the Amiga, I wouldn’t have done any of this. The Director’s Cut started as a straight AGA upgrade to make it look as good as it could, but it took on a life of its own with new weapons and gameplay changes. It turned into a real labour of love, and I was over the moon with how well-received things like Super Sheep, the Holy Hand Grenade, and the Concrete Donkey were.”

How does Davidson feel about his rollercoaster ride with Worms nearly 30 years after its release? “It was the most amazing of times,” he smiles. “Making the game was as enjoyable as playing it, even if, looking back, I don’t see how I managed it! I just sort of got into this zone where I lived and breathed the game and seeing the enjoyment my friends had playing it just drove me to want to do more with it. I never thought I’d be sitting here talking about it nearly 30 years later. To anyone who’s reading and has an idea for a game, go for it. You never know where it might lead.”