Much has been written about cheating in games. The history of which is so old and entwined it's difficult to find its origins. Developers included cheats to aid development, from Manic Miner to Gradius. In computer games, it was possible for players to 'POKE' data values and change things, with old magazines printing listings of them. These allowed unlimited lives, fixing of glitches, and more. Computer games also had 'trainers' made, some even being sold – Castle Wolfenstein from 1981 had one by Muse Software. Some developers also built-in cheats, codes, and passwords for players to use. Put simply: the altering of games has always existed, even if it's less prevalent today than it was during the '80s and '90s.

Things get especially interesting when looking at the history of physical cheat devices that interface with game-playing hardware. Game Genie was not the first; Datel produced Action Replay cartridges for the C64 and other computers as early as 1985. There were also the Multiface peripherals for various computers, by British company Romantic Robot. These allowed not just cheats but also backing up games. Plus, there were other lesser-known plug-in devices. By the time Game Genie (initially) launched in 1990 the concept of cheat devices was already well established. Unlike Game Genie, however, none incurred the wrath of Nintendo, with a $15 million lawsuit ensuing.

There was this little Japanese company, Nintendo, which had this funny little console. Generally, people weren't excited about it. So we thought, that's interesting, but we ignored it

To fully document the Game Genie saga, we interviewed four key people: Ted Carron, Graham Rigby, Jonathan Menzies, and Richard Aplin. To tell the full, amazing story of this unassuming device, we've also supplemented their answers with quotations from other sources, including input from the siblings who founded Codemasters, the company behind the Game Genie: brothers David and Richard, and father Jim Darling. For good measure, we've also included quotes from Andrew Graham, creator of Codemasters' Micro Machines game.

Aplin was easy to track down, given his detailed and fascinating 2009 interview on GameHacking.org regarding Game Genie. "I did several versions of Game Genie, but not the very first NES one. I arrived at Codies just after the NES version launched in the US, and did several other formats; Game Boy, Game Gear, and so on. I did a really sweet 'Game Genie 2' for the SNES, but it never launched due to market conditions."

Aplin then pointed us in the direction of colleagues. "People significantly involved in the NES one were David, Richard, and Jim Darling, the Codemasters family. David started a small mobile games shop, Kwalee, and obviously knows the early days, litigation, Nintendo stuff, and might be happy to talk, now so much water is under the bridge; Ted Carron was part of the early team and still in Leamington Spa, he married a Darling; Graham Rigby now lives in Australia and did a lot of code-finding; Jon Menzies wrote a lot of software at Codemasters; Andrew Graham wrote the NES ROM software for Game Genie as well as other stuff, some NES games, lock chip work and so on. He also flew to Taiwan to work on production/debugging of the ASIC for the NES Genie."

"You seem to have the core people connected to Game Genie," says Rigby, seeing the interviewee list. "I was the first to start work on the Game Genie, besides the original trio. Ted Carron, Rich Darling, and Dave Darling were the inventors and responsible for the birth of the Game Genie."

David, the elder of the Darling brothers and Codemasters co-founder, is the key person to describe Game Genie's conception. It all started with the launch of Nintendo's grey NES console in America, which initially didn't garner much interest. "We went to the CES show in Chicago," David told us a few years back. "The industry used to go every six months, in Chicago and Las Vegas. There was this little Japanese company, Nintendo, which had this funny little console. Generally, people weren't excited about it. So we thought, that's interesting, but we ignored it. By the next show, six months later, Nintendo was everywhere. It took off across America. Even at petrol stations, they were selling Nintendo games. So we thought: this is the machine we have to be involved with."

Letting The Genie Out Of The Bottle

A 1993 Super Play interview with David confirms it was at the later Vegas show where they made their decision, "I went with Richard and a guy here called Ted Carron to one of the Las Vegas Computer Entertainment Shows, where we realised just how big Nintendo was over there. When we came back we were thinking 'right, we've got to somehow get into this'." Of course, to develop for the NES required an expensive license from Nintendo and, in that same Super Play interview, David reveals the Japanese giant wasn't interested. "To be honest, when we went to CES, we tried to talk to Nintendo about doing games for them, but they gave us the cold shoulder because we hadn't booked an appointment. After that, we just saw doing it without them as a challenge."

"At the time it wasn't easy to get a licence and we didn't need one, so we went ahead without it," states brother Richard, interviewed by EDGE magazine on the making of Micro Machines. "We produced our own development systems and games. The hardest part was finding a way around the protection on the NES, so our games would not be treated as 'counterfeit'."

We tried to come up with a game concept that would appeal to absolutely everybody. We thought that to achieve this you'd have to give the game loads of options, so people could make it as hard or as easy as they liked

This defiant seed, planted due to Nintendo's apathy towards Codemasters, would ultimately cost Nintendo millions of dollars, and it was all down to Ted Carron. Reverse-engineering the NES, cracking the security, building Codemasters' in-house NES development kit, and ultimately designing Game Genie itself was all down to Carron's technical expertise. Andrew Graham, in the same EDGE article on Micro Machines, humorously describes how in April 1989 he first encountered Carron's genius. "I converted Treasure Island Dizzy using Codies' homemade dev system. Ted had made a rather 'Heath Robinson' system which consisted of a PC connected to a Commodore 64 connected to a box full of wires and electronics, all hooked up to a consumer NES. They mailed the lot to me in Scotland. His subsequent NES dev kits were altogether more compact. They were given codenames from characters in Blade Runner."

The initial plan had been for Codemasters to branch out from computer development and start making console games. Keep in mind the company's early successes were with budget-priced titles and sports simulators. The intention of the latter being to tap into pre-existing audiences for something, such as BMX fans or rugby fans, rather than grow a fan base from scratch. So while Codemasters' earliest foray into NES development was porting pre-existing computer games, such as Dizzy, David and co were thinking of ways to reach wider audiences – and what wider audience is there than every single game owner?

"We tried to come up with a game concept that would appeal to absolutely everybody," David told Super Play in 1993. "We thought that to achieve this you'd have to give the game loads of options, so people could make it as hard or as easy as they liked. This, in turn, got us thinking about how neat it would be if we could modify every game like that, but we thought it wasn't possible with Nintendo games being on cartridge. You can't change the ROM. We were wrong, of course – it is possible. You don't have to change the ROM, you just have to fool it a bit."

David elaborated on this when we spoke to him many years later in 2013. "We used to have ideas sessions every Wednesday or so, where we'd just go to our flat and try to come up with ideas. So we thought, how can we make these games really special? One idea was we could have a switch on our cartridges, to choose the number of lives, or which weapon, or something. Then we thought: well, maybe we can make an interface that will work with other people's existing games and give extra features? Because all these kids in America, playing Super Mario Bros., they would love that."

Those idea sessions took place with brothers David and Richard plus the aforementioned Ted Carron. "After going down to London to launch the Atari ST version of International Rugby Simulator, I was staying over at Richard Darling's flat in Leamington and I had a meeting with him and Dave," recalls Carron. "They explained they wanted to break into the NES market, and wanted to brainstorm different ideas to add something original to the games. At that meeting, the idea came up to create a device that somehow altered the behaviour of existing games. I went back home and created a prototype."

We asked Carron what it was like reverse-engineering the NES for this prototype and also about his makeshift dev kit for the system. Sadly, given the legal troubles back then, he was somewhat reticent, "No comment regarding reverse-engineering the NES. Yes, I did build a makeshift NES development kit and it did involve a Commodore 64. I am sorry some of this is a bit cagey. Even though it was a long time ago those were very big court cases, with a lot of money involved and lots of scary American lawyers."

We thought: well, maybe we can make an interface that will work with other people's existing games and give extra features? Because all these kids in America, playing Super Mario Bros., they would love that

Although Carron didn't want to describe the process, it would have involved using a logic analyser. An intimidating looking device with numerous cables that are attached directly to the circuitry of a shop-bought NES, in order to decode how it functioned. When Aplin arrived at Codemasters they were using LA4800 analysers. "They look more impressive than they are; they're quite simple," he explains. "You have a bunch of digital inputs, say 32~48, and the LA4800 samples them at whatever speed you want, say 20Mhz. It then displays the results as either wiggly lines, for a single input, or numbers. For a set of inputs like a data bus, you'd tell it to group them together and display as a hexadecimal number. You could trigger it to start capturing on certain conditions. Typically we'd connect 16 address lines and 8 data lines and a handful of other control lines, and it would show you what the CPU was doing to memory as it ran. For example: read two instructions, write a RAM location, jump somewhere, and so on. That's pretty much all they did; you'd have to pore over the results and figure out what was going on."

Despite the complex and laborious nature of reverse-engineering, the completion of Game Genie was relatively quick according to David. "About six months for the initial NES version, I guess," he told Super Play in 1993 when asked about how long it took to pull together. "Doing hardware was a new thing for us, and we had to get in quite a few new people and lots of new equipment!"

Menzies also described how the in-house software came about, corroborating statements about Blade Runner codenames being used. "I wrote the ROM for the in-house game development system, Nexus 7," he says. "I believe the actual ROM for the Game Genie user interface was written by Andrew Graham. My main contribution to Game Genie, along with Graham Rigby and another guy whose name escapes me, was creating the Genie codes."

Cracking The Code

For the first Game Genie, on NES, players were presented with 16 letters each corresponding to a hexadecimal value, and three dashed lines allowing codes of 6 or 8 characters to be inputted. The device itself came with a booklet containing codes for all the latest games at the time. The choice of letters to represent hex values seems entirely arbitrary, though. It might have been to increase the likelihood of real words forming codes, or to make writing down new codes easier. For example, 'PIGPOG' on Super Mario Bros., which randomly changes enemy placement, is much easier to remember and tell friends about than the hex equivalent of '154194'. Unfortunately, no one we interviewed knew why the menu interface formed as it did. Carron would only cryptically state that "the hex code thing was for legal reasons."

With the device itself in the works, Codemasters would need a publisher and distributor. Camerica handled things initially in Canada while Galoob Toys covered the US, before eventually, Galoob took over entirely. "There was a company called Camerica," Carron recalls. "Actually, it was more the head of that company, a guy called David Harding. He was a friend of Dave and Richard and he introduced them to Galoob. He was also the Canadian licensee for Game Genie."

David Darling also described these events to us back in 2013. "When we worked with Mastertronic, this guy called David Harding was their Canadian distributor. He set up Camerica. So when we developed Game Genie, we asked him if he wanted to distribute it in North America. I think he thought 'this is too big for me'. So he took it to Lewis Galoob Toys in San Francisco and sold the idea to them. So we signed a contract for them to distribute it."

With Ted Carron handling the hardware and Andrew Graham programming the user interface, the last major hurdle was finding codes for existing games, to be included with the final product. Due to the versatile nature of Game Genie, which would allow codes for all NES games – past, present, and future – each code for each game would need to be manually discovered through trial and error, and any found codes were unlikely to work on other games. There was no one-size-fits-all, meaning Codemasters needed to bring in more people, so as to 'brute force' their way through the hexadecimal.

It was like Christmas every other week. When things ramped up with Galoob's involvement we were getting about 10 games every other week. It was awesome

Rigby explains how the start of his Codemasters career was as one of their code finders. "I knew Ted Carron through mutual friends, back home, and he asked if I wanted to find cheat codes. In the initial days, I think it was Camerica who were involved, supplying some games for us to get codes for. Galoob came later. That's when things really took off with more games needed for the codebook; I think it was 255 games for the release. That relationship with Galoob also led to the Micro Machines games."

The process of searching for working codes would have been slow and tedious, though as Menzies explains, the team came up with little tricks to speed things up. "I wired up a Commodore 64 to control a prototype Game Genie using a pop-up utility on the Commodore, so we could type codes directly in hex, which was a big improvement over using the NES controller. Also we managed to daisy-chain two Game Genies so we could enter up to six codes at once, which sped things up a bit. There were a lot of games, but I specifically remember finding the codes for the Mario and Mega Man games, since I had so much fun playing them. I would first finish them without cheats because I didn't want to ruin the fun!"

"It wasn't very glamorous," adds Rigby. "And it took about three days to go through a game, sometimes longer for some of the popular RPGs. The thing I remember most was the very first dev kit; it was a few rows of switches soldered onto the top of a black 5.25-inch floppy disk box. They were binary switches and you had to flick the position to 0 or 1 to represent the address and the value you wanted to change to." Unglamorous perhaps, but for anyone who liked games it must have been an incredible experience. In fact, in an online interview, Richard Aplin once stated: "Graham Rigby was the main Codemeister – he lived in a room full of nothing but shelves and racks of NES games – he had every NES game in every territory!"

To have access to every NES game ever released, anywhere, is unbelievable, and we asked Rigby how accurate this description is. "Yes, completely true!" he laughs. "It was like Christmas every other week. When things ramped up with Galoob's involvement we were getting about 10 games every other week. It was awesome. At the time, a lot of the games weren't available in the UK, so you were seeing a lot of new stuff. Obviously, some games weren't great, and you still had to put the time and effort into those too, but generally, I played a lot of brilliant NES games in my early career. And then the SNES came out. For a gamer, it was great."

With hardware, software, and codes in place, Codemasters' new product was almost ready to market – it just needed a catchy name. Originally Game Genie was called the 'Power Pak', with EDGE magazine stating it was renamed by David because players were granted "three wishes" when entering codes. Whatever the reasons, the new name and looming red genie figure became an iconic and likeable brand. Amusingly, the Galoob and Camerica iterations were quite different; the Camerica genie emerges from flames wearing a futuristic sci-fi visor. Did anyone know, we asked, who drew or conceptualised these figures? "I can't recall who," Rigby admits. "It was a genie figure so it represented the name on the box."

Carron adds that "the packaging was developed by Galoob so I have no idea who the artist was." Aplin isn't any wiser. "Nope, am guessing maybe Galoob, but not sure. Codies retained a lot of control over the product. Anyway, that stuff is marketing, so who knows!"

Nintendo vs. Galoob

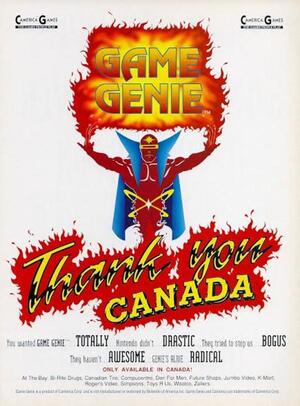

The NES version first hit store shelves in 1990. Though Game Genie would eventually become known exclusively as a Galoob product, at least for a time, Camerica sold copies in Canada. While Galoob faced a court injunction from Nintendo to halt sales in the US, resulting in lengthy court proceedings, the Canadian courts dismissed Nintendo's case against Camerica. This turn of fortune led to Camerica producing the infamous "Thank You Canada" poster, stating: "You wanted Game Genie. Nintendo didn't. They tried to stop us. They haven't. Genie's Alive. Only available in Canada!"

The court case between Nintendo and Galoob is perhaps the most interesting part of the Game Genie saga, since it pits two enormous corporations from opposite ends of the planet against each other, battling over a toy conjured up between two brothers and their friend in a flat in Warwickshire. While some sources try to portray the fight as being David versus Goliath, that's not accurate. Galoob was founded in 1957 and is regularly cited as being one of the ten largest toy companies in the US, with the LA Times stating its total revenue for 1989 at $228 million. Also don't forget that Nintendo had, since entering the US retail market, attempted to gain a monopoly over the manufacture and sale of video games, mostly through underhanded means. These were both 800-pound gorillas trying to take each other down in open court – meaning it's also extremely well-documented, with all the papers online. It was an arduous battle, as summarised in the final judgement: "This case has included one and one-half years of litigation, [and] a two-week trial..."

I remember Nintendo winning a temporary restraining order to stop the sale of Game Genie. When the restraining order was given to Nintendo it was a big blow

Carron does not have pleasant memories of events and was reluctant to say much. "It was long and frustrating. This, like a lot of other things, is covered by all kinds of legal restrictions and non-disclosure agreements. Americans take that kind of thing very seriously."

Interestingly, many people don't realise that it was Galoob that fired first, and not Nintendo. On Thursday 17th May 1990, Galoob initiated events by pre-emptively seeking a court judgement that Game Genie did not violate any of Nintendo's copyrights, simultaneously seeking an injunction to stop Nintendo doing anything that would interfere with sales of Game Genie. Galoob went so far as to request that the court forcibly prevent Nintendo from ever revising its own NES hardware to make it incompatible with Game Genie.

By trying to manipulate how Nintendo manufactured its own hardware, it seems like Galoob was deliberately taunting the Japanese giant into retaliating. It makes one wonder, would such epic litigation have taken place if Galoob had just left the sleeping giant alone? Of course, Nintendo retaliated, filing its own complaints and requesting injunctions against Galoob. On Monday 2nd July 1990, about 46 days later, the courts issued a preliminary injunction, favouring not the instigator Galoob, but Nintendo. Galoob would have to stop selling Game Genie while the court case played out. The injunction was later affirmed by the court of appeals Wednesday 27th February 1991. Only on Friday 12th July 1991, some 421 days after Galoob's initial filing, did the courts and District Judge Fern Smith issue a final ruling in favour of Galoob. Nintendo appealed and the entire thing ended only on Thursday 21st May 1992, roughly two years later, still in favour of Galoob. Nintendo isn't in the habit of losing legal battles, but the Game Genie saga constitutes one of the few times it did.

Rigby recalls the initial restraining order as galvanising the team. "I remember Nintendo winning a temporary restraining order to stop the sale of Game Genie. When the restraining order was given to Nintendo it was a big blow. After that I think the guys [at Codemasters] started getting a lot more involved then, feeling it was their field, their area of expertise, so they had something to contribute."

Back in 2013, David told us about a particularly memorable moment in the proceedings, where Nintendo's most famous employee got involved. "It was quite a complex case and there were lots of different parts. They even had Shigeru Miyamoto in court – he came to San Francisco. They were saying that because the player was plugging in the interface and making Mario jump higher, the player was making a derivative work, and we were helping him infringe copyright. In the end, the judge said it was not permanently changed when you unplugged it, and for a derivative work to exist it has to be permanent. We were not called to the court, but we were heavily involved in the legal side. The lawyers wanted to know exactly how it worked, so asked us thousands of questions."

Some of the team's tactics were quite interesting, highlighting the hypocrisy of Nintendo, as Menzies explains. "I helped with the lawsuit by creating non-Game Genie codes that could be entered into an official Nintendo game's own password system and would crash it, cause graphical corruption, weird behaviour, and so on. Basically all of the things that Nintendo's lawsuit accused Game Genie of doing, so we could say to the judge 'look, this isn't anything to do with us, Nintendo's games do this on their own, it's just how video games work'."

Even after the July 1991 ruling though, it would be a couple of years before Galoob and Codemasters were paid out. At the start of the court case, Nintendo had to pay a $15 million bond as security for the preliminary injunction against Galoob. When Nintendo lost the case it appealed the execution of that bond, and only on 17th February 1994 did the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reject this. The money went to Galoob, with some making its way to Codemasters. In a BBC news report from around the time, it's stated the brothers from Warwickshire won "more than £2 million from the computer giant Nintendo". In this same BBC news report, Richard Darling is quoted saying, "We have a lot of good creative people here, developing good original products – games and things like Game Genie. For a company like Nintendo to think just because they're powerful and dominant in the market place they can stifle that sort of thing, it's wrong and I'm glad they didn't succeed."

The courtroom victory became legendary, and something for Codemasters always to speak proudly of. In a later British TV documentary, called It's a Living, family patriarch Jim Darling stated, "We've developed a very high level of expertise in copyright and patent issues, so if people try to suggest that we are infringing then we will defend. I'm quite happy that we don't ever infringe and will always defend. It doesn't matter how big they are."

A final twist in the tale, and something which was seemingly never documented anywhere, is that much later Codemasters and Galoob would fight each other in court. This revelation comes courtesy of Aplin. "One recollection I have is that we spent about as much time suing Galoob – our business partner! – as Nintendo spent suing us. Goes to show when there are millions at stake, nobody plays nice. I can't tell you much detail; I wasn't involved in that stuff directly. I'm not sure it's as interesting as it sounds – it was just two companies with a lot of money at stake butting heads. We had the product and the patents, they were the US distribution mega-corp. I am guessing they would've had no problem with 'Hollywood accounting' and that they viewed us as an inconvenience – big business ain't pretty. Obviously, such stuff was kept private from the world and I don't know any juicy details. I doubt those who do know, primarily Dave Darling, will be willing to talk about that side of it even now. I'd point out that such stuff happens all the time and only rarely is the linen aired in public."

Even while the wrangling with Nintendo played out, Codemasters and Galoob knew they had a hit product on their hands. It had sold well before the injunction, and continued to sell in Canada under Camerica. April 1991 archives from United Press International state that, at the time of the injunction, Galoob had manufactured 15,000 units and had orders for an additional half a million more. Based on Canadian sales, and were it not for the injunction, analysts at the time estimated Galoob could earn as much as $30 million from Game Genie per year. It was clearly a hit. Obviously, the companies wanted to ride that wave, and following on from the NES there would be Game Genie for SNES, Game Boy, Genesis/Mega Drive, and Game Gear.

Aplin explains how he reverse-engineered other hardware formats to create new Game Genie models. "We used LA4800 analysers. I spent a lot of time in front of those. We bought a bunch as they were cheaper than other models. We used them both for code-finding and debugging our own hardware. I personally was completely prohibited from using an LA4800 on a console with a commercial game cartridge plugged in, because even the act of monitoring the data bus technically created a transient copy of some – a few! – of the bytes of game ROM inside, which were copyrighted, and hence could weaken our case in any legal battle. That was quite frustrating, but after years of legal pain with the NES Game Genie, Codies were understandably careful. Obviously, if we'd been allowed to disassemble game carts it would have been much, much easier – but the results would've been legally tainted. Meaning obtained via copyright infringement. I had to keep a written diary every day of what I did, how I figured stuff out, and so on, to provide a paper trail in court."

Sega The Savour? Not Quite

A lot has been written and said about the fact Sega seemingly officially endorsed the Game Genie on its hardware, putting its seal of approval on the product. However, this situation is not as amicable as many presume. Sega only allowed the Game Genie because Codemasters gave an ultimatum to Sega, resulting in an 11th-hour deal – one which has never been documented before.

"This was obviously secret at the time, maybe it still is," explains Aplin. "Codies built their own cartridge manufacturing facility on-site on the farm. If I recall, they got as far as manufacturing a small run of carts before they sensibly confronted Sega and said: 'This is what we're going to do. Would you like to sue us or reach an agreement?' They'd been very careful about the legal side and were fairly confident they could win in court if it came to it. As you'd imagine, Sega losing such a case could potentially open floodgates, so the rest is history. Codemasters had balls, that's for sure. I have the greatest respect for what Dave, Rich, and Jim Darling achieved in the face of considerable opposition from some very large companies."

The products were in full production, the companies were legally safe, and the money could roll in. In fact, there was such urgency to meet demand, as Aplin explained, that Codemasters and Galoob had their own hardware teams working in parallel creating prototypes. "Both teams made FPGA-based prototypes for some models," says Aplin. "The reason for the duplication of effort was simply because it was so vital to get products out and in the stores. The redundancy was worth it."

Books of new codes for new games continued to be sent out to those who bought Game Genie. Magazines printed reader codes. Game Genie became a successful phenomenon replicated across multiple formats, and with a legacy that continues to this day (recent console flash carts have Game Genie functionality built directly in). Back in the day, we almost had Game Genie sequels for the 16-bit consoles; the SNES successor even reached the functioning prototype stage. "I think I did a Game Genie 2 prototype for the Genesis but it didn't get as far along, software-wise, as my SNES follow-up," Aplin recalls. "The second one for SNES was lovely – I put everything in there I could possibly think of, and Fred Williams wrote some great software."

I do remember one day when Dave Darling handed out some royalty cheques; I was pretty happy with mine but the guy sitting next to me – who will remain nameless – got a cheque with at least one more zero on the end

There was so much money involved with the Game Genie project it's difficult to work out the numbers. In February 1993, David was quoted stating the NES release had sold 2.5 million copies; later sources claim the entire Game Genie range, altogether, sold 5 million copies. Meanwhile, the International Directory of Company Histories claims Game Genie made Galoob $65 million in 1992, dropping to $4 million by 1994. GamesTM magazine later claimed Game Genie generated over $140 million in total, a figure repeated by other publications. Whatever the precise figure was, it's safe to say Game Genie over its entire run made a lot of people shed loads of cash. Still, we asked everyone we spoke to if they knew the precise figures.

Rigby states he isn't aware of the total, but Aplin – who also doesn't know the precise figure – gives us some idea with the following anecdote. "I do remember one day when Dave Darling handed out some royalty cheques; I was pretty happy with mine but the guy sitting next to me – who will remain nameless – got a cheque with at least one more zero on the end. It wasn't easy; the legal battles were long-winded, frustrating, sometimes scary, and definitely expensive, but Codies battled through it and won in the end. Ted Carron, part of the early team, profited pretty handsomely from the Game Genie. Basically, a few people made a bunch of cash – ain't that always how it goes?"

Not everyone profited though, as Menzies reveals. "I pretty much got ripped off, as I never got paid much, despite once working continuously for three days without sleep. In the end, I was just staring at the hex numbers saying 'they're so beautiful...' I remember once asking for a tiny royalty, about one-quarter of a percent, but they said, 'Oh sorry, we'd love to, but the royalties have already been divided and we can't change it now.' I was naive, and they didn't mind taking full advantage of that fact, a pattern that would repeat itself over the next few years. Still, they were generally good times at Codemasters, and the money didn't seem so important at the time."

This article was originally published by nintendolife.com on Sun 23rd May, 2021.

Comments 98

This is like the very first skyward sword amiibo. Except it worked on multiple games and was actually cool.

I remember having the game genie when I was a young un. I also remember being disappointed that it didn't change the games as much as I thought it would. Maybe it was this that led me to view cheatcodes and walkthroughs a bit of a waste of time... until you complete it first at least. Oh well, one legacy gone and resigned to the ages.

I can't remember the early 90's year I got the Game Genie for my Game Boy. It was my most wanted Xmas gift of all time that year and opening that present Xmas morning was excitement overload. I remember though realizing the commercial(s) for it were just slightly over exaggerating some of its abilities (like what @LavaTwilight just said). Some games it did a lot for and some hardly anything at all. Also I noticed if your game was NOT listed in that giant code book you were sh#t out of luck And yeah @Manjushri some games it really screwed them up to unplayable status it made using it for cheating pointless.

I remember their nods saying it could potentially damage game carts. Like save corruption wasn't a thing when using CR batteries...

There were so many games during the 8 / 16-bit era with brutal difficulty. Without save files as well. Maybe that explains the sales figures. A helping hand to finally see those end credits.

I was familiar with the product at the time. It’s good to know the story behind it. Very interesting.

I LOVED my Game Genie. Glitching out Super Mario was fun as heck.

Very cool story, game genie was so much fun back in the day. My brother was amazing at discovering codes outside of the ones available in the manual. If you knew what you were doing, you could do some incredible things with it. To this day I still don’t know how he did it.

I hate that Nintendo has such a long history in the courtroom. I’ll be phasing them out of my game purchases this year; I don’t feel right supporting them long-term, anymore.

More articles like this, please. It makes all us old-timers feel refreshed.

NINJA APPROVED

This was the only way I was able to see the ending of certain videoganes as a kid (I was stuck on the last level of Star Tropics for years until this came along)

There were downsides though. I remember using a cheat in Zelda II that replaced my shield spell with the Thunder spell. Except, it wouldn't let me get the actual Thunder spell later on, and it would never let me through the barrier at the end. But at least it helped me get a decent trial run in before I went back without cheats to beat it without assistance. Definitely one of my proudest accomplishments in my early gaming days.

@Pokester99 Please understand

and the game genie is dead and nintendo lives on. and besides i am a real gamer. i do not have to cheat.

@tntswitchfan68 lol... Wtf is this.. real gamer. Lol. Anyways I had one I got bored with trying to make it worth using most times. It was cool enough but never really did much to help me.

I got my NES game genie as a reward for sitting quietly at the dentist when I was a kid. I had to have 2 teeth removed and wasn’t looking forward to it, mum said if I get it done without drama she’d get me the game genie so I didn’t even flinch.

Still got my Game Genie for Gameboy, gutted I lost the book.

My copy of Tetris has a sticker on the back of the cart with a bunch of Game Genie codes.

These type of devices have always fascinated me and driven a game "hacking" side-interest. The first one I had was an Action Replay for the Gameboy. My old notebook with handwritten codes was found in my parents attic just a couple of years ago. Somehow I had been able to make a "walk in the air" code for Super Mario Land using the trainer function. I had devices like this for pretty much all consoles up until PlayStation before jumping into PC gaming and the endless modding opportunities that was possible before DRM became a thing. Nowadays I use the original NES Game Genie to test the physical romhack repros I'm making. Good times

This is a great story. I had a Game Genie as a kid. I never knew or even considered the legal implications of it.

It's fun to explore a game without having to be good at it. Without the countless hours of frustration. I think the community understands that better nowadays. Thanks to Game Genie games were so much more accessible then.

I forgot that existed

I was a boring purist when it came to playing games in the 80s and 90s. I almost felt guilty when someone gave me the cheat to starting the original Zelda game as +. There’s a few rare cases where you almost needed a cheat to get through a game but overall I never understood the point to using cheats (and especially the game genie which many of my friends enthusiastically used and boasted about), because if you “win” something by cheating, you didn’t actually win, and being dishonest to get through a game means you just wasted time in my opinion.

@LavaTwilight I was always a bit disappointed in what these cheat carts could do too. The advert reproduced in the article promises being able to jump higher, punch harder and run faster. 99% of the time most games just had a code for infinite lives and that would be it.

I had all of the game genies back in the day. Think I still have them all.

Many modern games have cheats, you just have to buy them from the in game store with real money.

This is a great article. I love pieces like this and would be happy to see more of them on this site.

Still have mine for Nes and Snes but I hardly ever use it anymore. It seemed cool at the time but then I just felt empty inside because I wasn't earning my victory in games. It's much more fun to get good then butcher the game by cheating.

I love hearing about these interesting parts of gaming history. I rented game genie a few times. Stopped when it started screwing up my game.

@Nontendo4DS I used that code! As it happens, you can knock out King Koopa in one hit.

The usual self- righteousness coming thru in a few posts.

I got my kids one and they had a ball with it.

It's been over 30 years and people, to this day, get judgmental and emotional over what OTHER people do for their free time.

To the folks spewing the "real gamer" tripe, what do you gain from that? You're not going to change anyone's minds railing against cheating, and they're having fun while you grumble about their habits.

First, excellent story!! Thank you very much for this piece (nice Sunday read).

Second, I never had one growing up, but some of my friends did. Still was not able to beat one single game on the NES until I was much older (I was young when this came out).

@Kiyata Video games, all of them, are a waste of time. Many leisure activities are, when we get right down to it, they contribute nothing to work or society. And yet they remain valid because they're what people do to relax, wind down, and prepare for work and obligations. How people go about their leisure activities isn't your business or anyone else's.

I had it for the NES and SNES. I used it a lot for the NES, due to the number of games on that platform that had unfair, brutal difficulty. I didn't used it much for SNES. By that point, the difficulty level for games was much more fair.

And I always roll my eyes when moralistic types come on these boards and preach about "purity in gaming." What the hell does that mean? Let people play the games they want to play and enjoy gaming the way they want to enjoy it. If playing match 3 on a phone is what floats their boat, fine. If they can only game playing 60FPS AAA exclusives, fine. I'm so tired of the judging nature by many of this hobby that is suppose to be fun.

Game Genies destroyed the 72 pin connector on many NES systems. This already faulty device was made even more fragile with the Game Genie.

I relied on the game genie just to make most games run properly after a few years. Those cartridges degraded quickly and blowing into them to remove dust or whatever only got you so far. The game genie actually made them run.

Wow this just gave me flashbacks from childhood. I had a friend who had a game genie. We used it to play super mario 2. Don't remember what cheats we used though, but I remember the awesomeness! Thanks for the memories.

@tntswitchfan68 Game Genie is still easily acquirable, and it’s also built into pretty much every emulator for systems that utilized it.

Also lol real gamer 😀

@BloodNinja I imagine Nintendo's courtroom battles over copyright and patent infringement as being like that of Thomas Edison's, particularly with the Kinetograph, one of the first movie cameras.

Back in the day, only his company was allowed to design and manufacture movie cameras, and to make movies; no one else was legally allowed to, or else Edison would sue them for copyright or patent infringement.

Nowadays, you have multiple film companies and different manufacturer's for cameras, so Edison was ultimately the loser of the war, even if he won the early battle.

I bet, someday down the line, Nintendo may come around to more outside people doing stuff with their IP (like these 4K HD Super Mario 64 tech demos as rendered in the Unreal 4 game engine), and we are kind of already seeing it: like with Cadence of Hyrule, Mario+Rabbids: Kingdom Battle, and the upcoming Mario movie.

@sanderev nintendo only managed to get rid of the physical devices and limit it to the hackers. now days, people with homebrewed switches/3ds's/wii u's use a action replay program

I beat Ninja Gaiden 2 with this thing and the game was still stupid difficult. I only needed the infinite lives and weapons codes anyway since the savepoints were nonexistent and you could only use like 4 ninja stars per level.

Awesome end boss fight and the cut scenes for an 8bit game really added to the cinematic ending. One of the few difficult retro games worth finishing. Gives you a real sense of accomplishment.

My games wouldnt work without it it seemed. Was like a drug for the NES.....Hmmmm.......

Thank you Mr. Szczepaniak and Nintendo Life for a nice long article. Game Genie rocks!

Hey BBC! It is completely moral.

I hacked my 3ds for the cheat codes. Gives me that Game Genie feel.

An innovative product for its time. I didn't have the pleasure of having one here in Brazil but some friends did. Awesone and cool

@AstroTheGamosian Definitely a great comparison, there!

NINJA APPROVED

I remember using this a lot for Final Fantasy 1. The infinite gold code took away a lot of grinding. You still had to grind levels a bit and you still started with 0 gold and had to be able to afford the item so there was a small grind in the beginning but it was such a help to a 5yr old RPG fan.

|sf>I used to create codes on the internet for the Gameboy and Game Gear genie devices. Many codes did small things like altering the music, but once in a while I would bump into something special (like skipping levels). There weren't many people online who created codes (especially when it came to Game Boy & Game Gear), so it seemed like a challenge.

In modern times, such a massive number of games are being released on the systems like Switch that it's hard to keep track of all the games themselves.

@rjc-32 cool story mate

@BloodNinja Hilarious.. hate Nintendo cause you want to mod and cheat on games.. I am sure they are crying at night missing out on deadbeat cheaters. Why not make a game yourself?

@Papichulo Newsflash... you didn't beat the game. This probably why so many people watch streamers instead of playing themselves.. like people who watch cooking shows but don't cook

@Kiyata I think even some magazine I had read had talked about those sorts of cheats are really more something to mess around with AFTER finishing the game properly.

I do remember using my GG to have infinite lives in Pac-Man for the Game Boy before asking myself what the point of playing the game like that was. I think even then I knew that was a score attack game with no ending.

I also one remember one of the games I had as a kid was Roadrunner's Death Valley Rally for the SNES, and that game had anti-cheat programming put in it. Put it in the GG and it would crash EVERY TIME.

I'm sure I only beat that game once, and then with its own built-in code for tons of lives (which I recall required pushing a pretty uncomfortable combination of buttons on the title screen).

@ChakraStomps I'll repeat my question from earlier. What do you gain from this behavior? You're not going to change anyone's minds and being smug isn't going to win you any friends, so please, tell us what you get out of this. I would love to know why you care what other people do with the products they bought.

No different than SXOS.

I miss cheat devices!

I don't want to have to grind, especially on games that I've played before and ones that take 500 hours to play!

I still have my NES Game Genie and recall mostly using for extra lives. I didn't get into changing jump heights and stuff. On the SNES I had the Action Replay as it could learn codes and doubled as an adapter to play NTSC games. I never knew there was such history behind Game Genie.

@ChakraStomps Spare me your needless and excessive negativity. Troll elsewhere.

@Zebetite Hey let's see that stay consistent okay? How much hate people give against people buying limited edition stuff, scarce things from scalpers? It seems if people spend a lot on rare things then all the hate rips from these comment threads but it is ok to be huge cheating/ripping/pirating etc and then we hear.. "what do you care what someone's does with the products they bought" — The reason I care about that is so many people will spend all day everyday complaining on spending money when they could work a part time job and buy whatever they want. But no, we have to hear about protecting rippers, piracy, and then that leads to crappy free-to-play garbage with endless paywalls to satisfy all the cheapo freebie wannabe gamers.

Glad this old Gen Xer doesn't have many friends in this era, you all don't know how to work for what you want.

One of my older cousins was a wizard with Game Genie & Game Shark codes back in the day. Man used to somehow create his own codes and break games in unimaginable ways and keep a handwritten notebook of everything lol so wild. Good times.

I remember being so hyped to play games with the Game Genie. I don’t remember having any luck with entering a code and playing through a game though. Seemed to glitch a lot.

I remember using a Game Genie on Earthworm Jim on the SNES and we got it so we had infinite big gun and invinciblity, great fun, until we got to one of the Bosses and because of the cheats being on it was imposible. Got stuck on some spikes which you could not jump out of but because we were invincible you were just stuck there.

Fantastic article.

It can't be underestimated the amount of SNES Game Genies that were sold in the States after EGM printed it's infamous Street Fighter II "boss code".

Sadly I never had a Game Genie but I did have the Action Replay for my GameBoy.

I remember actually having quite a lot of fun using the code finding facility, where you would tell it you were looking for a particular type of value and then you'd play the game, push the reset button and tell the Action Replay if the value you were looking for was greater or smaller than the time before and eventually it would home in on the correct value.

GameGenie was probably the better of the two products I think, purely because it could be used to make changes to ROM code while Action Replay was limited to fixing RAM values. So while Action Replay could give you infinite lives, GG could do more varied stuff like edit sprites, change background colours or alter gameplay (as long as you have enough code slots!)

I was old enough to look at this thing for what it was and never ever used one, actually sorry I did use a free disc 'I got on a magazine so I could play my american copy of animal crossing on my uk gamecube.

This thing was the scurge of the industry for years and the one of the biggest reasons I never trust a pokemon without my trainer name. It always amazes me how much people like this type of thing when it is such a problem for the industry overall.

We need more talk about Dizzy and the Yolkfolk in all articles going forward please.

Fascinating article, thanks. The Game Genie was a huge deal for NES players in the U.S. I remember getting mine and struggling with getting it properly placed into my NES the first time. There were a bunch of games I'd given up on and never played anymore that I suddenly was playing a lot (Blaster Master!) once I had invincibility/powered up weapons/etc.

Interesting article. I love learning history of video games, especially Game Genie.

I remember fiddling around with Game Genie back in the day and creating new codes in my free time. It took a lot of searching for patterns and then a bunch of trial and error, but it was fun seeing what would happen.

I think studying the Game Genie and GameShark helped me develop a basic idea of how games worked at the time.

@BloodNinja It's what happens when you don't get laid. Let him play with himself til he's tired 😄

@BloodNinja Well, in my eyes, a real gamer does not need it. But, I will not tell others who to feel.

@SlimPieEats cheating is not for real gamers. That is how I see it.

Who would have thought after all that brilliance, all that legal work, and all that defiance of sticking it to The Man......Codemasters would eventually become part of EA....the OTHER company blackmailing platform vendors with their own cartridge production at the time. Small world. Small, rotting, festering world.

It was a great product though! And honestly, Codies can shove all their racing games, this is the one and only product I really know them for. I used my Game Genie extensively, saw the end of so many games I otherwise wouldn't have with it. It was from the original run before the restraining order on them. Still have the book, and box around, as well as a Game Boy Game Genie still unopened in-box I believe. Not bought as collectibles, but original purchase. And my NES slot really shows my extensive Game Genie use.....

@Papichulo LOL

@tntswitchfan68 I don’t think there are any fake gamers, and playing a game with a cheat or trainer doesn’t all of a sudden make you fake. Some people use cheats or saved states to practice to become better, I would hardly call them “fake,” when their real-life gameplay is on par with a TAS or something.

@tntswitchfan68 ... My Gramma hates when people make trades in Monopoly. It is not in the rules she says we are cheaters. She's a real gamer not one of us boardwalk stinking traders.

@SlimPieEats cheating is making it easier.

@BloodNinja It means you are not up to the challenge.

@tntswitchfan68 In a video game? A moderate challenge is ok. I prefer physical challenges to digital ones, so that I actually walk away with some level of self improvement that’s on a meaningful level.

@tntswitchfan68 getting boardwalk on A trade makes Monopoly easier. You are trying to say your game playing is better then some other game player and that is one of the most nerdy things I have ever heard. But you bad game playa. Keep on being you.

@BloodNinja Well, OK that is up to you. I just personally do not like it myself.

@SlimPieEats Well, I just like playing the game it was intended, but I apooogize if what I said was arrogant.

@tntswitchfan68 salud .

This was a good writeup 👍 I had the Game Genie for Gameboy and loved it. It had a handy little button on it for you to disable/enable the codes mid-game. So if things got janky, you could turn off the codes temporarily and it would often save your butt without having to restart.

It came with a little code book, but it didn't have as many codes as I hoped. But I spent a lot of time trying to find my own codes and still have a little notebook with the codes I found.

@tntswitchfan68 "i am a real gamer. i do not have to cheat."

For me it wasn't about cheating, it was about breathing new life into games I'd already played to death. Or beating a game that was simply too difficult no matter how hard I tried (Robocop, Battletoads).

I also loved to chuck in random codes to see if I could find something cool, or totally glitch things up so the levels would look completely different.

@Prizm OK. Sorry if I came off harsh.

Brilliant article.

Unfortunately given Kim ted income as a teenager I would always spend my hard saved cash on a new game versus an action replay or game genie. That said I was always curious. I remember there being coded that allowed to you to “be@ the bosses inSF2 world warrior SNES. Didn’t work terribly well but at the time gamers were so desperate for that!

Very interesting, but poor Menzies. Despite being one of the original core developers, they took advantage of him. In the end, it's all about the moolah. Once the money rolled in so did the ugliness and greed. All very common.

Why add cheats to a game when you can sell them as micro transactions

@Torn completely agree. You will be taken advantage of if you don’t advocate yourself sooner than later. This comes from naïvete so I get it, but it’s awful how greedy people can be to those who CLEARLY made a huge contribution. Shame on their wicked nature.

@Zebetite a little harsh there on Kiyata, no? I think Kiyata’s angle came from the competitive aspect than just criticism of your own personal gaming time. There is a difference on how you beat a game - if you modded it, you cheated plain and simple. But like you said , after accepting that, it doesn’t really matter how you play the game as long as you are having fun. And I don’t see how gaming is a waste of time, even if it did not contribute to society. If it’s not an addiction, there’s a lot toward mental health when it comes to relaxing and doing “nothing”.

I believe the Game Genie disappeared when the PS joined the show and ppl preferred to use the “Game Shark” instead......

@Would_you_kindly so true. The industry wised up and decided to sell them. With a Game Genie nowadays, companies would sue successfully that their profits are being taken away.

@Magrane yeah things like unlock all items in resident evil & treasure maps that show you where all the collectibles are in Forza etc just ridiculous

I had Game Genie for NES back in the early 90's. Good times 😁

@Nontendo_4DS Just reading your comment made me remember that hammer suit when I was kid. Man that really brings back memories. You felt op as hell with that bad ass suit.

Imagine proudly thinking of yourself as a 'real gamer'. LOL How embarrassing that must be.

Game Genie ruled the world back in the day. I admit I was one of the ones to have one on my Gameboy. Its too bad they didn't have one on the DS and now the switch.

The only reason I got SX OS was for the Cheat Option.

It's great.

After having played Xenoblade on the Wii, WIiU (both never finished,but quite a lot of hours into both), then on the =NEW= 3DS XL again, never finished but a ton of hours and then a =NEW= 2DS XL where I finally beat it, when I got it on the Switch, I loaded up the Cheat Menu, LVL99, no cool down, 99 every item, max affinity coin, and breezed right through the main game so I could refresh myself on the story again.

Got to Future Connected a few weeks later and didn't use any cheats. If I were to play future Connected again, I'll use cheats.

@Atomic77

DS had an Action Replay, pretty much the same thing as Game Genie

Somehow I missed one interesting tidbit when first reading this article earlier in the year:

"Interestingly, many people don't realise that it was Galoob that fired first, and not Nintendo. On Thursday 17th May 1990, Galoob initiated events by pre-emptively seeking a court judgement that Game Genie did not violate any of Nintendo's copyrights, simultaneously seeking an injunction to stop Nintendo doing anything that would interfere with sales of Game Genie. Galoob went so far as to request that the court forcibly prevent Nintendo from ever revising its own NES hardware to make it incompatible with Game Genie."

@Magrane I know Nintendolife is reposting articles but it still seems odd to respond to comments from half a year ago.

Game genie was awesome. I even had one for the PS1 (wasn't a game genie, forget the name) that let you edit things like having Sephiroth in your party in FF7 or Aerith staying alive. Was pretty cool and didn't hurt that it allowed you to play burnt discs either..

Such a shame this ever made it to mainstream, this crap ruined so much in gaming.

@dew12333

Exactly what was ruined?

@Spider-Kev Pokemon trading for one.

@Zebetite Nah. I don’t think there’s ever a timeline for not being able to reply to older comments. That sounds silly to me.

@UglyCasanova Game Shark!

@Magrane There's a reason why necroposting is something that's been derided on the internet for decades, but you do you.

@Zebetite never heard of it as a thing or even a negative. But hey, thank you any way for the attempt to enlighten me (without any guidance) about the fact I responded instead of addressing what I originally said!

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...