When it comes to the history of Lucasfilm Games and LucasArts, there is no shortage of compelling "What ifs", with the studio having a veritable graveyard of projects that were killed before they had a chance to reach the market.

From Star Wars originals like 1313 and First Assault to adventure game sequels like Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels and Sam & Max Freelance Police, there has been an abundance of unrealized titles that have since come to light from across the company's 40+ year history, which have both excited and frustrated fans in equal measure. So we thought we'd take the time to look into one of our personal favourites — Indiana Jones & The Iron Phoenix — speaking to the developers of the game and looking at various other articles and videos on the subject to piece together the history of its development, and the Dark Horse comic books it eventually inspired. Ironically, though, our story doesn't actually begin with The Iron Phoenix, but with another cancelled Indy project: the lesser-known educational title Young Indiana Jones at The World's Fair.

The Next Adventure

During the development of Indiana Jones & The Fate of Atlantis in 1992, those within LucasArts began discussing what the next Indiana Jones adventure game might look like. This resulted in a small group of developers — led by the Loom creator Brian Moriarty — beginning work on an educational game for Lucasfilm's edutainment division LucasLearning entitled Young Indiana Jones At The World's Fair, which was set to be based on The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles TV show that had debuted earlier that same year.

Over the years, a few details have surfaced about this game, thanks to articles and interviews, with previous reports claiming that the project was supposedly not well-liked internally and would have been purely focused on real historical elements rather than the supernatural. Ex-LucasArts employees, for instance, remember the game focusing on the creation of the machine gun synchronization gear for World War 1 biplanes and have also claimed in the past that it would have also seen players learning about (and potentially meeting) historical figures like the musician John Philip Sousa.

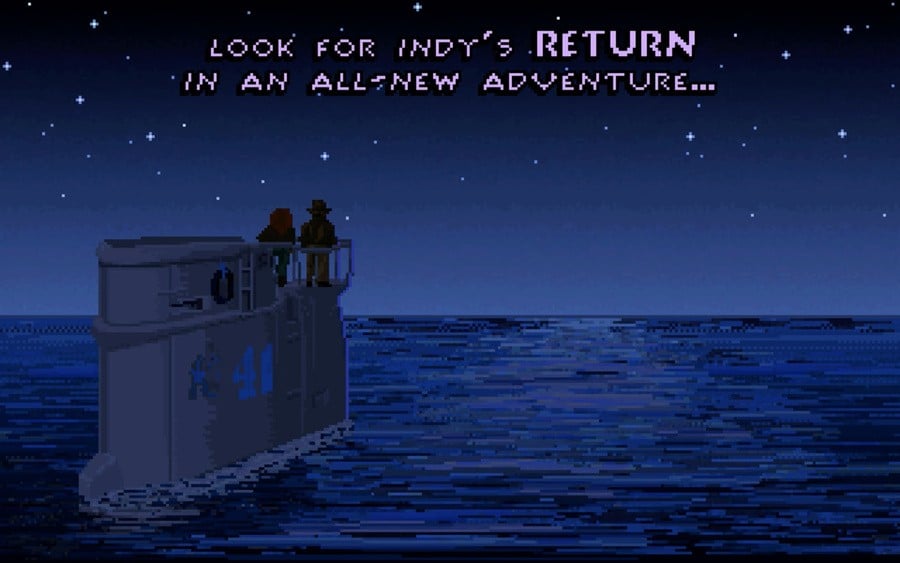

The game was teased at the end of Fate of Atlantis, with a short message during the ending credits ("Look for Indy’s return in an all-new adventure. Perhaps as a much younger man…"). But the project was later dropped altogether in 1993, presumably due to the low viewership ratings and cancellation of the Young Indiana Jones TV show.

In the aftermath of the Young Indy project's cancellation, those inside LucasArts once again started to pitch ideas around the company for a new Indiana Jones game, with the concept this time being to make more of a straightforward sequel to the Fate of Atlantis. Joe Pinney — a Lucasfilm Games' QA tester and an individual who had previously worked on Young Indiana Jones At The World's Fair — was selected to lead the project (his first time in such a role), while the Lucasfilm veteran and close personal friend of George Lucas, Hal Barwood, provided his services as a story consultant and the resident "Indiana Jones expert".

Barwood had previously been the director of Fate of Atlantis (as well as its co-writer alongside Noah Falstein), but, at the time, had chosen not to direct the new adventure game, as he wanted to focus on smaller, non-SCUMM-related projects. So, instead, he took on more of an advisory position on the project helping the inexperienced lead adjust to his new role and assisting him in hashing out a story that would do the Jones' character proud.

I made lists of cool artifacts. The Philosopher's Stone seemed kind of dumb at first. Like, it's a rock? I guess? However, I thought all the Albertus Magnus alchemy stuff was great.

The two, therefore, got to work on completing an initial design and, by March 1993, managed to put together a 50 to 60-page design document/story treatment named Indiana Jones & The Key of Solomon. This story would have taken place in 1947, following the events of World War II, and focused on a group of Nazis on a quest to find the Philosopher's Stone — a mystical artifact capable of resurrecting Hitler.

"I made lists of cool artifacts," Pinney tells us, giving us an insight into how he landed on the game's central MacGuffin. "The Philosopher's Stone seemed kind of dumb at first. Like, it's a rock? I guess? However, I thought all the Albertus Magnus alchemy stuff was great. I resisted the stone until the resurrection stuff combined with the "what-do-Nazis-like" stuff clicked.

"[As for why we decided on the post-war period], it was because that post-war period is amazing — the closing of Berlin and all that stuff is wild — and because this version of what-Nazis-like required it."

This story in this document started with Jones travelling to the Soviet-controlled sector of Berlin to retrieve the Key of Solomon (an object that would have served a similar function to Plato's Lost Dialogue in the Fate of Atlantis) from a monastery before being captured by the Soviet major, Nadia Kirov. Kirov initially suspects the archaeologist of being a Nazi thief, imprisoning him in a set of cells. But Indy manages to knock out the guard and escape with the scroll, embarking on an adventure that would take him to Ireland, Kyiv, Tibet, and Eastern Bolivia.

Besides Pinney and Barwood, two other people were also reportedly part of the project at this early stage. This included Bill Stoneham (a LucasArts background artist who had also previously worked on the special effects for The Fly) and the artist and animator Anson Jew. Both of these men had also previously worked together on the cancelled Young Indy project, with Jew having also been involved with the original DOS release of Fate of Atlantis.

"Who worked on what [at LucasArts] was usually a confluence of different factors," Jew tells us. "Typically several projects are going on at once, staggered at varying stages of production. As some projects start dying down and shedding workers, others are just starting up and picking workers up. I happened to be getting off another project, was available, and had some Indy experience."

With an interesting design starting to take shape and a small team gradually forming, it seemed like the new Indy project was picking up steam. But just as soon as the development started to grow some legs, the project would be dealt its first blow as Pinney left Lucasfilm Games for undisclosed personal reasons. In the aftermath of this, the senior member of staff at LucasArts scrambled to find a replacement, but there were very few experienced project leads who were not already engaged elsewhere. As a result, LucasArts assigned the veteran employee Aric Wilmunder to lead the project alongside Stoneham, who was already working on the project.

"Joe was eventually replaced by Aric Wilmunder and Bill Stoneham," Jew tells us. "Neither Joe, nor Aric and Bill, had shipped a game as project leader by that time but most people wanted to give them the benefit of the doubt."

Fleshing Out The Design

Wilmunder had joined Lucasfilm Games back in the mid-80s and had worked various roles within the company since then, introducing various improvements and changes to the SCUMM (the Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion) engine, and serving as a localization manager for the company.

To those who made a habit of sitting through the credits of each and every LucasArts' game, he would inevitably be a familiar name, having been involved with some of the company's most well-known titles. But, despite that, he had never actually led a project at LucasArts himself.

"I was approached," Wilmunder told Daniel Albu, in an episode of Tech Talk, earlier this year. "It was like, 'We have this project'. Joe Pinney, I was aware, had left the organization but I didn’t really know what or why that was."

According to Wilmunder, in the same interview, he didn't feel like he had room to start over from scratch, so instead, he took a look at what Pinney had already created and decided to flesh out what was already there, giving more depth to the characters and locations.

"I wanted to take as much of the good from it and then move forward," he told Albu. "And I think Joe had done a pretty solid job working on the story. The way I look at games is that Joe had created breadth. And by that, I mean, he had created locations and characters and [he had] created the playing area where the character would be moving around in. But [...] there wasn't the depth and what makes areas interesting to visit."

Over a period of months, Wilmunder put together a new design document, while the other individuals assigned to the project, like Bill Stoneham and Anson Jew, created storyboards, character art, animation tests, and background mock-ups to figure out what the project would look like. In the end, what they decided on was what they described as a "comic book" aesthetic featuring characters that were similar in size to the ones seen in 1993's Day of the Tentacle and 1995's Full Throttle.

Wilmunder's design document, dated October 6th, 1993, states about the art style: "We’re striving for a unique look, exceptionally dramatic animation, and high-end action play. Characters will be big (84 pixels high) and comic-book (large blocks of color, just two shadow colors for each color area, but not outlined or cartoonish like DOTT characters). This gets us more expressive characters that are actually easier to create and animate the highly rendered, rotoscoped-looking characters. This look also scales exceptionally well."

According to Jew, in an interview with Mix 'n Mojo, this style had actually come about due to a compromise between himself and the leads on the project, who had initially wanted to pursue a more realistic style — something that was not possible, Jew had reasoned, due to noticeable color banding issues.

Jew told Mix 'n Mojo, "I was asked to design a realistically proportioned, fully rendered Indy more than twice the height of most of the characters in previous games but was only allowed to use the same amount of color slots per character as the smaller characters in previous games. Unfortunately, when you double the size of a character in a fully rendered drawing, you also need twice as many colors. If you don't, you get very visible color banding--resulting in a blocky and/or faceted look to the characters. [...] So there was a bit of tension over how many color slots get allocated to animation and how many to backgrounds. I would have loved to have had more shades of color to work with in order to render Indy properly."

Besides changes to the art, the document also makes references to some new action scenes that would have played out alongside the more traditional inventory puzzles. These consisted of first-person sections, including a motorbike escape from the Soviet-occupied East Berlin and a scene two-thirds of the way in where Indy would have had to pilot a JU52 seaplane through the Andes Mountains.

Inside the document, there is also a reference to Dragon's Lair-inspired sections too, which would have more closely replicated the "action-packed sequences of the Indy movies". These would have had the player quickly click on an object onscreen to have the archaeologist perform a series of fast-paced animations, as opposed to relying on the standard point-and-click interface. This is an idea that Jew had proposed, with the animator working up some rough tests, including a segment that would have also taken place on the seaplane in the later section of the game.

Jew tells Time Extension, "I was playing with the idea of doing puzzles that involved full-sized characters in close-up or medium shots (what else can you do from the interior of a seaplane?) instead of the typical small character running around in a wide environment shot. It was a fight between a Nazi and Indy in the cockpit."

Jew has mentioned this section before in interviews, giving a slightly more detailed account of how this would have worked in a conversation with Mix 'N Mojo: "I devised this puzzle of Indy inside the cockpit of a small plane getting battered by a huge Nazi on top of him. You would punch and punch this guy, and barely feeling it, he would simply return your punches. You could try to do different things to defeat this Nazi--trying to hit him with various objects in the plane. But in the end, the solution was to grab the wheel and turn the plane upside down. Then, suddenly Indy is on top of the Nazi and can defeat him."

German Censorship & Outsourcing Issues

With a new design document in hand, everything seemed to be gradually coming together, with the project even getting another name — Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix — courtesy of the Sam & Max Hit the Road co-director Mike Stemmle. There was, however, one small problem that had started to be voiced from outside of the company — concerns over how the game would be marketed and released in Germany.

After the war, Germany had placed a ban on symbols and iconography related to "unconstitutional organizations", making it difficult for companies to market games depicting the Nazis without edits being made to the material. As a result, the company Softgold, which had handled the German release of Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis (alongside other LucasArts games) had sent a fax to the company in June 1993, outlining its concerns about the game's story: namely, the idea of raising Hitler from the dead. This has frequently been cited as the death blow for the project, including by individuals such as Hal Barwood and Anson Jew, but is something that Aric Wilmunder has stated could have easily been changed.

As Wilmunder told Albu in the Tech Talk interview earlier this year, "That wasn’t the sole reason or maybe not even the key reason. [...] I could take that out of the game in five minutes. And we could have made all the issues with Softgold go away."

Instead, what seemed to be the most significant obstacle facing the Iron Phoenix was simply a lack of internal resources, with LucasArts having a shortage of people to throw at the project to bring it to life. As a result, much of the game's development was spent brainstorming ways of building the project without having to scale up internally and pull people away from other projects. The first proposed solution to this came courtesy of Jack Sorenson, the director of business operations at LucasArts, who suggested the team outsource much of the game's development to a Canadian company called Strategy First.

Strategy First was a games company based in Montreal that had become privy to a Canadian tax scheme that allowed them to write off the costs of a game's development if the money was being used to enter new industries. Because of this, they had approached Sorenson in the past with the offer of funding one of LucasArts' projects, with the condition that the game would need to be built in Montreal to qualify for the incentives.

This, of course, sounded like an excellent proposal to the LucasArts' higher-up but Wilmunder had some doubts about Strategy First's ability to make a decent adventure game due to their lack of experience with the genre — a feeling that only grew stronger as the developer ended up making semi-regular trips to Montreal only to discover the team was all pre-occupied working on other projects.

"[Sorenson] didn’t understand that this wasn’t sausage being cranked out through a meat grinder," Wilmunder told Mix 'N Mojo. "You needed teams with experience and talent. Bill and I tried working with these guys, went to Montreal on a number of occasions, but the only thing the team had ever built was an ice hockey game. Building an adventure game was beyond their skill set. I’d come home discouraged and I remember how these guys chain smoked and so my clothes smelled like an ashtray when I’d get home."

The arrangement with Strategy First only lasted for a few months, during which time LucasArts exchanged frustrated letters with the team in Canada, questioning their scheduling of the project and complaining that the new art being worked on had "lost the flavor" of the original pieces that Bill Stoneham had developed. Eventually, LucasArts' cut the cord and went back to the drawing board, to figure out a new way of bringing the project to fruition. This is when Wilmunder suggested something rather unexpected — that the team use live-action performance instead of traditional animation techniques.

Full-motion video was something that was starting to become more common in the industry in the early '90s, thanks to games like Night Trap, Sewer Shark, The 7th Guest, and Myst, but was something that LucasArts had yet to experiment with. Because of this, Wilmunder felt it could potentially utilize the technology to get around issues the project had been facing, so suggested that the technology group inside LucasArts film a couple of test scenes from the design doc with a group of actors.

Speaking to Daniel Albu, Wilmunder said, "I always had this thought, if you look at what we were doing with Indy, these teams would have 40-50 people, and it would be one project lead, three - maybe four - scripters, and 3 or 4 musicians working part-time (maybe to the end of the project), and then you’d have maybe 30 or 40 animators. Art was — I’m not going to call it the bottleneck — but it was the largest physical user of human resources."

Footage of these tests has since surfaced online via an interview with the ex-LucasArts' employee Mike Levine and features a recreation of a scene that would have taken place in Ireland section of the game. At this point in the story, Indy would have already found the first piece of the Philosopher's Stone that was capable of turning base metal into gold, in a church in Kyiv, and had taken a boat to Ireland to locate a second piece believed to be hidden inside an old monastery.

When he arrives in Ireland, however, he soon discovers that the monastery that he was searching for now lies in ruins, leading him to travel to the local pub where he hears of a druidic cult that has been terrorizing the population from a local eccentric named Costello.

Travelling with Costello to a set of stone ruins, Indy learns more about Costello's friend, a police constable named O'Leary, who went missing after a run-in with the cult, before both men are swiftly captured and brought to the head priestess. The head priestess then murders Costello with a stone bowl carved out of the missing piece of the Philosopher's Stone and tries to do the same to Indy, before our hero manages to turn the tables and escape bowl in hand.

In the footage, the Lucasfilm designer and artist Collette Michaud took on the role of the druidic priestess, while an unknown actor was cast as Indy. The belief was that if the footage went down well internally, the team might be able to convince Harrison Ford to take on the role, but unfortunately, George Lucas took one look at the project and decided the technology wasn't quite there yet. Because of this, the project gradually faded into the background as members of the team all moved on to other projects.

This wouldn't be the last anyone would hear about The Iron Phoenix, however.

What Happened Next

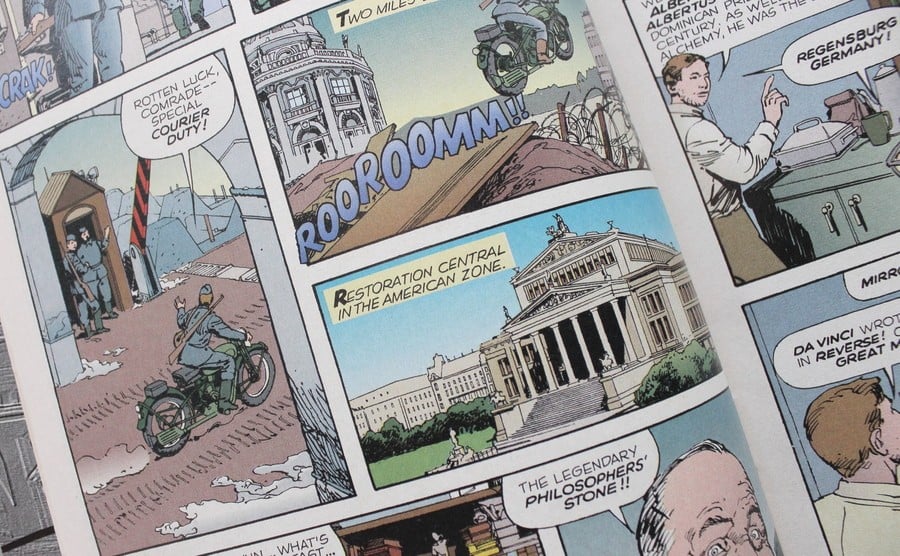

Sometime prior, between 1993 and 1994, LucasArts had made a deal with Dark Horse Comics to create a four-part comic-book adaptation based on the upcoming title. Dark Horse, in the past, had previously done the same for Indiana Jones & The Fate of Atlantis and had also published a bunch of its own original comics based on the Indiana Jones character, including: Indiana Jones and the Shrine of the Sea Devil, Indiana Jones: Thunder in the Orient, Indiana Jones and the Arms of Gold, and Indiana Jones and the Golden Fleece. So it was thought that an adaptation of The Iron Phoenix might be a good cross-promotional opportunity.

Few could have anticipated, however, that the game would eventually be cancelled and that the comic would end up being the only part of the project that would ever see the light of day in an official capacity.

In order to create the adaptation, Dark Horse assigned the American comic book writer Lee Marrs and the Argentinian artist Leo Durañona to work on the four-issue project, with the plan being for LucasArts to provide the odd piece of feedback to keep everything consistent between the comic and the game.

Marrs had previously made a name for herself in the world of underground comics with titles like The Further Fattening Adventures of Pudge, Girl Blimp before going to work in mainstream comics for companies like DC and Dark Horse.

Leo Durañona, meanwhile, had worked on horror magazines for Warren like Eerie and Vampirella, and had also contributed to Marvel comics series, such as Star Trek and Doom 2099. Both had previously collaborated on the 1994 comic series Indiana Jones and the Arms of Gold — an adventure that had seen Indy searching for the Chimu Taya Arms of Cuzco, an heirloom capable of reshaping stone.

As there was no finished game to show at the time, LucasArts presented Marrs and Durañona with a very basic outline of the story to help them begin their work, with Lucy Wilson, the director of publishing for Lucasfilm, and the project lead Bill Stoneham, being responsible for making sure the comic stayed true to what its developers were working on as time went on. According to Marrs, though, this was no easy feat, as the specifics of the project were constantly changing, requiring frequent alterations to the work they had already done.

Speaking to Comic Book Resources in 2015, Marrs said about the experience of working on the project, "They wanted the story to reflect what was in the game. By this time, I'd already been doing work in games and I saw that this game would probably never see the light of day. Their idea was to include the comic book in the game, and that was a nightmare. I would write a script, and then a couple of weeks later they would say, oh, it can't happen in Germany — it's supposed to happen to Ireland, now. Then I would have to change everything. But I put on a ten percent contingency fee on that, so at least they paid for all that indecision."

Despite these difficulties, Marrs and Durañona did eventually end up finishing the project to LucasArts' liking, with Dark Horse publishing the comic — following the cancellation of the game — from December 1994 to March 1995. The story in these comics, for the most part, closely reflects what we now know about the game from the design documents that have been released online — that is, except for the final issue, which switches the last location Indy travels to from the Amazon Rainforest to a manor in Koblenz, Germany.

That's not to say this final issue is entirely original, though, as it does still contain some elements that appear in the storyboards created for the video game project. This includes Indy opening a door to a secret room by solving a chess puzzle, uncovering a Nazi scheme to build their own Atom Bomb, and witnessing the Nazis using the stone to resurrect dead soldiers before they are eventually foiled.

Interested in finding out what the developers thought about the comic project, we reached out to several of the names we mentioned above, but most admitted that they had never taken the time to read it. The game's original designer Joe Pinney, for instance, was shocked to learn that he was credited in the comic, praising Dark Horse and whoever counseled them for including his name among those who came up with the initial story concept.

For fans of LucasArts' adventure games, the cancellation of Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix still hurts to think about all these years later, but it's clear when looking back over the project that its development faced a ton of issues that simply proved too insurmountable for the team to overcome.

Indy enthusiasts would instead have to wait until 1999's Indiana Jones & The Infernal Machine for their next great adventure — a story that would also be set after the events of World War II and feature a Soviet presence.