Don't worry – you're not suffering from déjà vu. If you feel like you've read this before, it's because we're republishing some of our favourite features from the past year as part of our Best of 2024 celebrations. If this is new to you, then enjoy reading it for the first time! This piece was originally published on May 3rd, 2024.

While the pandemic led to a

surge in pricesfor retro video games in the United States after years of the hobby already getting absurdly expensive, the opposite occurred here in Japan where you couldn’t walk into a used games store without tripping over good deals.

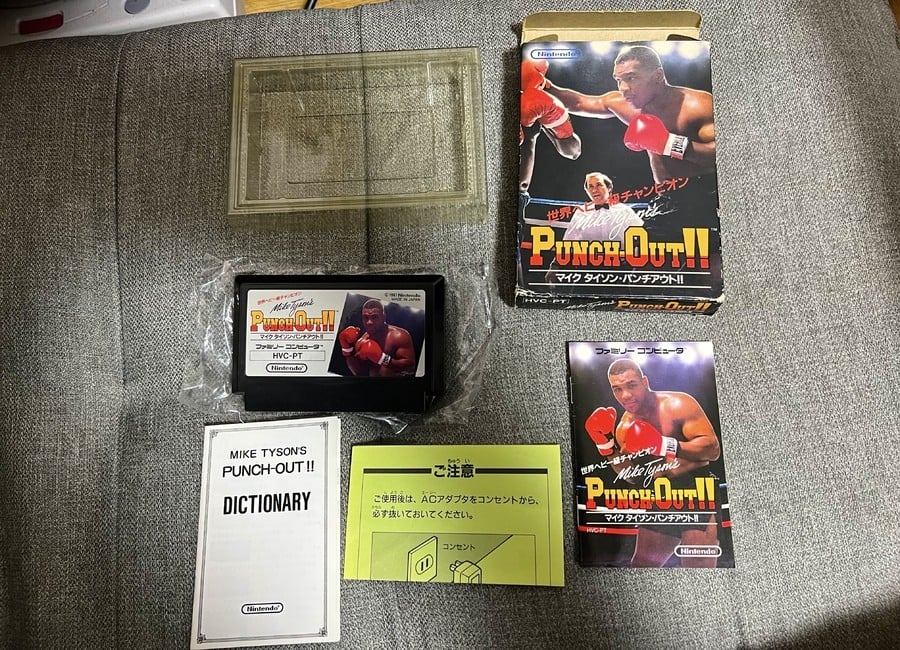

In 2021, I was able to get near-pristine copies of Metal Gear Solid: The Twin Snakes and F-Zero GX for roughly $20 apiece. As someone who’s currently aiming for a complete Famicom Disk System set, I’m halfway toward acquiring all roughly 200 officially licensed games thanks to generally low prices. In the over six years I’ve lived in Japan, it’s been great experiencing the thrill of finding complete in box Super Famicom games that are in near-pristine off-the-shelf condition.

And yet, something has changed. Earlier in April I tweeted about how the Surugaya I frequented for years is now a hollow shell of its former self. Once fully-stocked shelves are now half full, the Famicom Disk games are all gone, and those great deals I used to find are nowhere to be seen. I never expected my grumbling to really get much attention, but my tweets quickly went viral and even ended up being featured here on Time Extension.

Having gotten in touch with Damien, Time Extension's editor, I figured I’d weigh in with some extended thoughts on the state of retro game collecting in Japan. How exactly did we get here?

First, I should provide some background on who I am. I’m an American doctoral candidate who researches Japan-North Korean relations. Dreary stuff beyond the scope of this website, I know. But when I’m not researching despotic regimes and tense geopolitical problems for my PhD or writing articles as a freelance journalist, I like to kick back and enjoy some of my esoteric hobbies, which include collecting books, films, vinyl records and, of course, video games.

I grew up with my mother’s NES around the same time I got a Wii, which meant that I’ve always had an appreciation for video games new and old. I was around 10 or 11 years old when I realized that the NES had some great, timeless classics that still held up. My first system was the Game Boy Advance, which, in turn, unlocked an entire library of other games from the original Game Boy and Game Boy Color. I’m from Pittsburgh, PA which has always had a decent selection of retro games compared to most places in the Northeastern United States, so I slowly built up a sizable NES collection.

This was in the late 2000s going into the early 2010s right when YouTube was becoming a mainstream source of information to learn more about old video games. Thanks to the likes of The Angry Video Game Nerd and Classic Game Room, suddenly, more people were learning about once-obscure titles or reminded again of classic gems, leading to the demand increasing. This began the phenomena of video game collecting no longer just being a hobby, but a truly viable business on the secondary market where online resellers on sites like eBay could make a profit off of nostalgia.

Yet despite all of this, Japan for years remained largely immune to these trends. There have certainly always been video game collectors over here, but nowhere to the same extent as in the United States. Keep in mind that living spaces are generally much smaller in Japan, which means that there’s a limit to how much stuff one can keep. People are always unloading and reselling their old books, movies and games, which is why secondhand chains like Book Off and Surugaya have been so successful.

Some video games like Gimmick for Famicom or Magical Chase on PC Engine are extremely expensive, but that’s because those titles are legitimately scarce and never had large print runs. When it comes to standard fare like a boxed copy of Super Mario Bros. or complete copies of all the original Pokémon Game Boy games – where literally millions of units were produced – one hardly had to break the bank if they wanted to re-experience their childhood in Japan.

Unlike the United States, there is currently no culture here of organizations like Wata Games or Heritage Auctions artificially inflating prices as part of a speculation bubble that YouTubers like Karl Jobst have exposed as shady, to say the least. This accounts for why Sonic creator Yuji Naka was seemingly baffled that a copy of Sonic the Hedgehog on Mega Drive (and one not even in pristine condition) sold for over $430,000 in 2021. Retro video games being viewed as actual six-figure investments has simply never been a thing in Japan.

When I first came to Japan in 2017 to do an internship at a glass plant and later do a study abroad program, I arrived at a good time for collecting video games. I first lived in Ube, a rural town in Yamaguchi Prefecture with few tourists and a Book Off in the same neighbourhood as my apartment. Even now, the countryside is still the best place to find games in Japan due to the generally lower demand compared to the cities. But back then, though, large population centres like Tokyo and Kobe were not automatically bad spots for game hunting, either. You simply had to know where to go and be quick on the draw.

The COVID-19 pandemic later upended everyone’s lives the world over, and one of the ensuing responses was a rush of renewed interest in retro video games when people had to stay home with little else to do for months on end. When you pair this with the nonsense of speculator bubbles fueled by groups like Wata, it’s no surprise that it has become an even more expensive hobby than a decade ago. But this was largely something only affecting the American market.

Because there were no tourists in Japan for nearly two years due to the government closing the borders in response to COVID-19, stores had consistently stocked inventories of games. While many domestic Japanese consumers likely took advantage of this time, there were enough Zeldas and Metroids to go around since the hardcore collector base here has always been much smaller than overseas relative to the items that are available. I truly got some of the best deals I’ve ever experienced three years ago, but we are now unfortunately long past those days.

This brings us to the present and the sad display of Surugaya shelves that initially inspired me to write this piece. The way I see it, the problem is now two-fold — a sharp increase in foreign visitors and a sharp decrease in the value of the yen. With the number of tourists to Japan returning to pre-pandemic levels and likely on their way to surpassing them, people from abroad are coming to game stores found in the country’s urban centres en masse. One half of this crowd is your average tourist who simply wants two or three games as a souvenir to take home, while the other half is the inevitable scalpers who will clear entire shelves to resell on eBay.

As of this writing, 1 U.S. dollar is currently in the ballpark of around 158 yen. This means that a ¥5000 game to a Japanese consumer would only cost $31 USD to an American tourist, making it understandably a steal. I don’t blame any tourist who buys a couple of games they’re nostalgic for because it’s a good deal and cheaper than what they would get back home. You’re much more likely to find a complete-in-box Super Famicom or N64 game here than you would for their equivalents in the U.S., for example. But the other side of this is the scalpers who make the hobby worse for everyone in trying to turn a profit, leaving nothing left for those who actually want to play these games.

Another reason for the changing environment of retro video games in Japan is how some retailers are creating online portals which allow foreigners to buy items without even stepping foot in the country. Proxy sites like Buyee additionally serve as middlemen with how they purchase products on an overseas customer’s behalf, charge them a fee, and ship them out of Japan. This has led to a notable depletion of domestically available stock and is likely a major contributing factor to those empty shelves I’ve posted about.

I should stress, of course, that none of this is illegal, and if an individual consumer wants to buy an item for whatever reason, that’s completely within their right to do so. I’m merely providing an autopsy for how we’ve gotten to this point and explaining what the reality of the situation is. Retro video games, being long discontinued items which are often decades old, are a finite resource. That goes for anything "retro" – be it out-of-print books or first pressings of vinyl records. We also, fortunately, live in a time where emulation means that for most of these games, original hardware is usually no longer a necessity and more of a luxury for enthusiasts like myself.

But have things truly gone off the deep end for retro gaming in Japan? To begin with, the golden age of retro game collecting ended long before I even arrived here. If we turn the clock back to the early to mid-2000s before the advent of smartphones and YouTube, most of this stuff was in clearance bins or being sold for practically nothing apart from the truly rare stuff. By the time I came to Japan in 2017, those deals were already no longer to be found. With that said, the stuff I find these days is still generally much cheaper than what’s available in the U.S., something I verified when I recently visited my family earlier this year.

I’ve generally given up on retro game hunting in big cities, but every so often I’ll venture into the countryside to places far removed from tourist traps like Tokyo’s Akihabara or Kyoto’s Kawaramachi and find the hidden treasure I’m searching for. As one gets older and reaches the physical limits of their collection, you naturally become more selective in what you want to own anyway. I still have my goal of getting a complete Famicom Disk set and as far as I can tell, it’s not a system most people care about due to the hardware maintenance involved. I recently got an Analogue Duo and the sheer abundance of PC Engine games available in Japan means I’ll never run out of stuff to play.

While the online proxy sites are eating into places like Yahoo Auctions and Surugaya, I can still usually find what I’m looking for on sites such as Mercari and Amazon JP because it’s only really the bigger outlets which cater to foreigners. Knowing Japanese means that I can find the best deals if I frequently conduct new searches and bargain with individual online sellers for even better prices.

In situations like that, the prices really haven’t changed for me that much now compared to five years ago. Some games, like the Dragon Quest series, are always going to be readily available due to their large quantity, and the text-heavy nature of their gameplay means most non-Japanese speakers have little interest.

The state of retro video game collecting in Japan has undoubtedly changed, but despite some new challenges, I’m fully aware of how lucky I am to live in a country that’s still the best country for this hobby. It’s understandable why so many tourists want to take advantage of that when they come from countries with far worse scarcity like mainland China or South Korea. But if you do decide to come to Japan for the video games, I personally hope you’ll actually play what you buy.