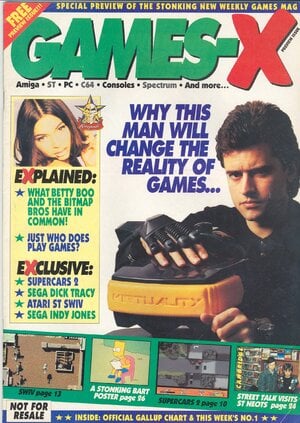

Back in the early 1990s, a technological revolution was taking place in the English Midlands. Located on a rather nondescript industrial estate in a leafy Leicester suburb was a company poised to alter the world of interactive entertainment dramatically; in its future, working relationships with clients as illustrious as Sega, Atari, Ford and IBM were still to come – as was a rather dramatic fall of grace.

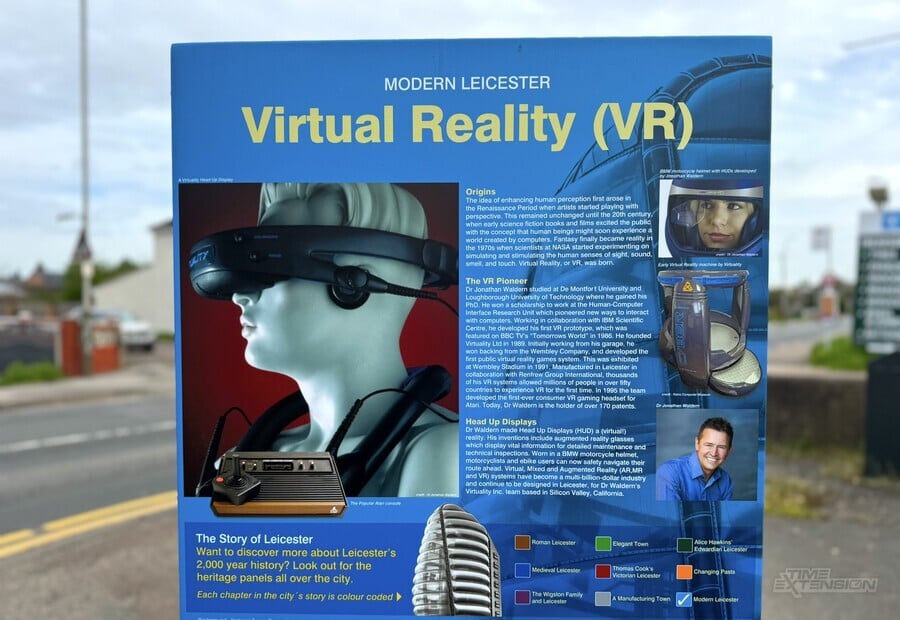

Founded by PhD graduate Jonathan D. Waldern, Virtuality was one of the first companies in the world to leverage the rising interest in Virtual Reality. As is so often the case, the technology had been knocking around at organisations like NASA and the US Air Force for some time, but it would soon become a focal point for the entertainment sector, with the 1992 movie The Lawnmower Man being a major catalyst in raising public awareness and interest.

It was amid this groundswell of activity that Virtuality became one of the hottest tech firms of the early '90s. Established in 1987 as W Industries and rechristened Virtuality in 1993, the company's first product launched in 1990 – the Virtuality 1000 series. Bulky and hopelessly outdated compared to the headsets we're accustomed to today, it will nonetheless have been the first legitimate VR product many people encountered, and it arguably laid down the foundations of what was to come.

"The 1000 series, which featured the iconic bulky headset, was essentially an Amiga 3000 with our own proprietary cards based on a Texas Instruments chipset," Don McIntyre told this writer in a Eurogamer interview a few years ago. McIntyre joined the company not long after gaining his MSc in Computer Science and was easily tempted to make the move from his native Scotland to the English Midlands by the promise of immersive reality. "It was the scale of ambition that really struck me. From end to end, the operation was slick. The machines looked good and, on the whole, functioned very well, and the software was literally years ahead of its time."

Matt Wilkinson, another former Virtuality staffer, had slightly less distance to cover than McIntyre. "I started my career at Rare, writing games on the early Nintendo and Sega consoles," he told Eurogamer. "I'd been making 2D games for about a decade at that point, and then Doom came out on the PC. All of a sudden, you were wandering around in what felt, to all intents and purposes, like a real 3D environment. Shortly after that, I heard of a company called Virtuality, which wasn't too far away from Rare's Warwickshire HQ."

Wilkinson took the plunge and decided to swing by the company's HQ. "One Saturday, I knocked on the door and gave some guy my CV. Completely out of the blue, he showed me around the place, and I was immediately fascinated. There were large pods to stand and sit in, hardware boards lying around all over the place, cables and bits of PCs in various states of disarray. Despite the fact I was in a windowless building on a Leicester industrial estate, the whole place felt high-tech and seemed to be a glimpse of where the future might lie. The guy let me have a go on Dactyl Nightmare, one of the company's early games. The game itself was terrible, but the experience of putting on a headset and being immersed in a world was incredible. I knew I wanted to be a part of this. The guy who opened the door turned out to be Jon Waldern. He offered me a job, and I accepted."

With the benefit of hindsight, it's easy to see why young developers like McIntyre and Wilkinson jumped at the chance of working at Virtuality – they were getting the chance to chart new territory. "Kids like us - who had grown up coding on machines like the ZX Spectrum, VIC-20 and BBC Micro - found their way into the games industry and brought with them a lot of ambition and energy," McIntyre told Eurogamer. "The concept of 'immersion' within a fully 3D environment had been around since Philip K Dick and extended a little further with Disney's Tron, and we grew up reading those books and watching those films. It felt like anything was possible."

The pathfinding being done at this point was remarkable, with Virtuality's engineers tackling the same issues that modern-day VR headsets are faced with – without years of prior experience to call on, like Meta, HTC and Sony. "The motion tracking was a magnetic sensor in the headset and in the handset, and although it was the best available at the time, it was still problematic," Wilkinson told this author for Retro Gamer magazine back in 2006.

"The cables could cause magnetic interference, and if the tracker moved too far away from the big, heavy magnetic field generating box, the tracker output became very jittery. The effect inside the headset was akin to having an epileptic fit and was very unpleasant. We had various algorithms for reducing the jitter, but they all basically consisted of taking several readings over a few frames and averaging out the results. Of course, this then leads to ‘lag’ where you feel like your head is in treacle. It was a fine balance, but when it worked correctly and with no interference, it worked very well."

Another problem that the Virtuality hardware engineers had to overcome was inter-ocular distance. "Basically, everybody’s eyes are a slightly different distance apart, so the two LCD lenses had to be mounted on motors to allow the player to adjust the distance between them," Wilkinson adds. "Then, of course, you have the problem that everyone’s eyes have different visual characteristics, and there is no room for spectacles in the headset. Each LCD display had a focus control at the side of the headset to allow the player to adjust them for each eye. The amount of complex and intricate hardware inside the second-generation headsets was incredible, and I take my hat off to the small group of hardware designers and engineers that worked at Virtuality with a small budget. What they achieved was incredible."

One of the first exposures the general public had to both Virtuality and VR in general would have been an episode of the now-defunct British TV show Tomorrow's World. Broadcast in November 1990, the segment showed Virtuality 1000 units being demonstrated – and predictably, it doesn't go entirely according to plan.

[This] is one of the classic Virtuality tales," Wilkinson told Retro Gamer. "They got everything set up in the studio ready for the live broadcast, and the pods were working fine. As show time approached, of course, the lights in the studio were all on, and the heat rose… and all of the Virtuality machines crashed and refused to boot. You’ll see four people sitting in the pods, moving their heads around and looking very VR-like, and it would cut between that and footage of the game they were playing. Well, the game they were meant to be playing – the footage was pre-recorded, and the people in the pods didn’t even have their machines switched on. It was hilarious!"

While Virtuality's origins were academic in nature, the company quickly identified "location-based entertainment" as the most viable commercial application of its technology, and 1000 series machines – available in both stand-up and sit-down forms – began to appear in arcades like the Trocadero in London, and even in branches of the high street retailer Beatties. Almost immediately, issues with the tech became glaringly apparent.

"At the time, a top-of-the-range coin-op game would cost you 50p to play, or perhaps a quid for Sega's fancy G-LOC R360 cabinet," explained Wilkinson to Eurogamer. "But those games were ones that everybody knew how to play. VR machines, in contrast, were totally alien. Therefore, you needed an attendant to help you into it, persuade you to put on the sweaty headset, and talk to you via a microphone to stop you standing in a virtual corner, staring at a virtual wall for your entire experience."

Speaking to this author on behalf of Retro Gamer magazine back in 2006, Wilkinson elaborates a little more on the issues faced by Virtuality. "We couldn't employ the same techniques used by console games because the whole point of our games was to involve turning the player's head, or the entire VR aspect becomes redundant. The moment you allow a player to control the direction of the camera by turning their head, you enter into a world of pain – how do you make the player look where you want? The number of times I'd watch people spend the majority of their three-minute experience standing in a corner and facing the wall was amazing."

The machines were already costly, and having to pay a member of staff to attend them drove the cost up even more. The end result was inevitable; arcade owners had to hike up the cost of entry to even have the faintest hope of recouping their investment. "The player would be charged on average four pounds to play for three minutes of not really knowing what they were doing," continues Wilkinson. "The VR experience is not something that can be quickly learned or mastered, so three minutes was never going to work. But these were amusement arcades, and the average arcade owner wants as many people in and out of the machines as they can in a day."

Despite these problems, Virtuality was heavily reliant on the location-based side of its business in the early years, as the market for owning one of these machines privately was tiny and certainly not enough to cover all costs. According to McIntyre, there were several units sold in the US and Far East, though – one was apparently installed on the Sultan of Brunei's yacht.

The shift to the Virtuality 2000 unit – which was, in effect, "a tricked-out 486 DX4 PC," according to McIntyre – improved the experience massively, giving players more complex, texture-mapped environments to explore which were a world apart from the flat polygons of the Virtuality 1000 series. However, it was clear that the company would need to find other revenue streams, and this led to a series of collaborations with outside companies, one of which was Sega.

The Japanese giant was keen to get into VR in some way and worked with Virtuality on its VR-1 ride. "Virtuality did a coin-op game for Sega, which involved being a gunner on a spaceship," Wilkinson told Retro Gamer back in 2006. "You didn’t do the flying, just the shooting, but it was easy to get shot by something you weren't looking at. Sega didn't like this because they said it was unfair to the player, so it was changed so that you would only take damage from something that was visible to you, which solved the problem. It wasn't until after the game was in the arcades that someone realized you could complete the entire game with one credit simply by staring at the floor the whole time! The big mistake that was made by Virtuality in the early days was trying to recreate existing console-type games in a VR headset, and it just doesn't work."

Virtuality would then team up with Atari to create a headset for its 64-bit Jaguar console, a project that came tantalisingly close to becoming a proper retail product. "We designed a very low-cost unit with head tracking," Wilkinson told Eurogamer. "The method we pioneered is actually what the Nintendo Wii uses to track the pointer, but in reverse; on our headset, the IR receivers were on your head, and the transmitter sat on your desk in front of you. Bearing in mind the relatively low cost, it worked remarkably well, but of course, it suffered from all the obvious problems – occlusion of the IR broke the tracking, turning your head too much would typically put one of the receivers out of sight of the transmitter and moving your head around could easily put you out of the ideal range, which impacted the smoothness of the tracking."

Ultimately, the headset never saw the light of day, despite being demonstrated at various trade shows by Atari. The company was collapsing following the poor commercial performance of the Jaguar and would fold entirely not long afterwards.

As these potential sources of income dried up, Virtuality found it had no option but to look elsewhere for cash – and this meant shifting away from the entertainment sector. Wilkinson was asked by Jon Waldern to join the company's Advanced Applications Group, which covered everything from "putting the user on an oil rig that was blowing up to creating a VR experience that – intentionally, I might add – simulated a migraine," he explained to Eurogamer.

This was a transformative moment for Wilkinson. "It was at that moment that I finally saw VR as something beyond just gaming; I realised that it had huge potential in all manner of other areas. Another AAG group worked on a project that was a simulation for anaesthesiologists; the user would be by the operating table of a patient, with an accurate representation of the controls and array of things available to a real anaesthesiologist, and their job was to make sure the patient was calm, stable and basically didn't die. The instructor could suddenly cause all sorts of things to go wrong that the user would have to deal with and keep the patient alive. This wasn't a game; this was going to save somebody's life one day. Similarly, the oil rig simulation was designed to test layouts and signage within a rig to see whether people would be able to follow the emergency instructions and get to the lifeboats in a very intense situation. Once again, that may have saved somebody's life, and that was serious potential."

Virtuality also worked with the Ford Motor Company to promote its Galaxy series in 1995, but these collaborations – while highly lucrative – couldn't keep the firm afloat. It's ironic, then, that two brilliant projects arrived just as the firm was collapsing on itself. The first was called Buggy Ball.

"Four players played simultaneously, and each was in a vehicle of their choosing, ranging from a heavy monster truck to a light and nippy buggy," Wilkinson told Eurogamer. "You were all placed in a huge bowl with a gigantic beach ball, and the aim was to score goals by being the person to knock the ball out of the bowl. We used a sit-down machine and a joystick to drive the vehicles, and all the while you need to be looking around you to find the ball and see who was about to ram you. It's such a shame that this wasn't the game that Virtuality began life with, because it might still be around today if it had." According to Wilkinson, it was "impossible to get Virtuality employees out of the damn thing" during development, and company tournaments were held on a weekly basis. It was even featured on an episode of GamesMaster.

The second project utilised Namco's Pac-Man, giving the player a VR view of the maze. "We tested an unfinished version of the game at the nearby DeMontfort University," McIntyre remembers. "There was almost a riot. Students were queuing around the building at one point, which proves to me that it worked."

Both arrived too late to save Virtuality. With 32-bit systems like the PlayStation and Saturn arguably providing a more visually appealing experience without the need to don a heavy headset, consumer interest waned almost to nothing. "The emergence of new console hardware was the death knell," laments McIntyre in his conversion with Eurogamer. "The experience lost its novelty, its appeal and ultimately its USP."

Virtuality was finally declared insolvent in 1997, with its assets being sold to Cybermind Interactive Europe. The arcade side of the business was sold to Arcadian VR in 2004 and then sold again in 2012 to VirtuosityTech. Undeterred, Waldren shifted his focus to the realms of 'Extended Reality' and wearable displays, founding DigiLens, Inc. in 2004. According to his LinkedIn profile, he has over 100 patents to his name.

Today, Virtuality has almost become a lesson about the dangers of bringing new technology to market before it's ready. "I think Virtuality's biggest mistake was thinking that games were what was going to make the company successful," Wilkinson told Eurogamer. "At that time, it was just never going to happen. VR was a gimmick that the company desperately tried to shoehorn a gaming experience onto."

He also feels that the public's perception of what VR could offer – which was hyped up by Hollywood – meant that the reality could never live up to the expectation, at least not when it came to 1990s tech. "When the movie Disclosure came out in 1994, it boasted a VR segment which really put a huge dent in what Virtuality was doing. Up until that point, we'd been happily telling the people who were paying us huge sums of money for their VR experiences that this was as good as they were going to get with the technology available at the time. Disclosure then puts a fresh Hollywood spin on VR, and suddenly all you need is a pair of lightweight glasses, and you're wandering around a photo-realistic version of the world; this was what people now wanted, not a simplified, polygonal environment."

As we all know, Virtual Reality didn't stay dead forever. The arrival of Oculus delivered a new era of VR, and today, players can choose from a wide range of different headsets to achieve the immersive gaming experience they crave. You'd think, then, that there would be little interest in the primitive tech peddled by Virtuality all those years ago – but you'd be wrong.

Fittingly, one of the best places to experience Virtuality's tech is Leicester, where the company was originally based. Just a short drive away from the original HQ (which has sadly been demolished to make way for a larger industrial unit) is the Retro Computer Museum. Founded by Andy Spencer, it is now the home to four fully functional Virtualty 1000 series units – two stand-up and two sit-down examples, all linked up for two-player action.

The custodian of these remarkable pieces of local history is RCM volunteer Simon Marston, whose relationship with Virtuality began as a fan. "It was 1992," he tells us. "I had just turned 18 years old, so I could enjoy the ventures of heading into Thomas' Arcade in Leicester. There, I found a Virtuality 1000SD (sit-down) machine, offering me the chance to play the game Heavy Metal for just £2 per 3 minutes. After spending around £10 each Friday during college breaks, I soon became an ace player. Thomas' then acquired a second machine. Only one person eventually beat it – and they turned out to have been a Virtuality engineer on a visit to update the software."

Marston's love affair with Virtuality went so far that he applied for a job with the company in 1997 – after several years of passing its HQ on his way to work – only to find out that it was going bankrupt. Even after it had gone under, Marston's interest refused to wane, and this led him to eventually acquire his very own unit.

"Fast-forward to 2013, and after hunting for years for information about the company and machines, I found one on eBay," he says. "I snapped it up – my very own Virtuality 1000CS (Cyber-Space) stand-up machine. It was not fully functional, so I spent a few months fixing it, and then I took it to a retro gaming event, where over 100 people were waiting for their turn. After all, these machines had not been seen in public for almost 20 years. It was shortly after that time that I joined the team at the Retro Computer Museum. Between 2013 and 2018, five more machines were acquired, four of which are installed for public use at RCM in Leicester."

Amazingly, Marston says that the museum's machines have been visited by many ex-employees from Virtuality, including Dr. Jonathan Waldern himself. "All of them are so appreciative that we are keeping these machines available for use, as they all enjoyed their time designing, building, and testing them all those years ago," he says.

In Marston's eyes, the Virtuality machines are a truly vital piece of history – not just for Leicester, which perhaps doesn't get the recognition it deserves in the history of VR development – but for the video gaming industry as a whole.

"I am sure I'm not alone when I say these machines are an important piece of computer and arcade history, especially to the Retro Computer Museum, as it’s based in the same city these machines were made," he says. "Virtuality was the world leader in VR at one point; without the company, we must question if VR would have made its reappearance again in more recent years."