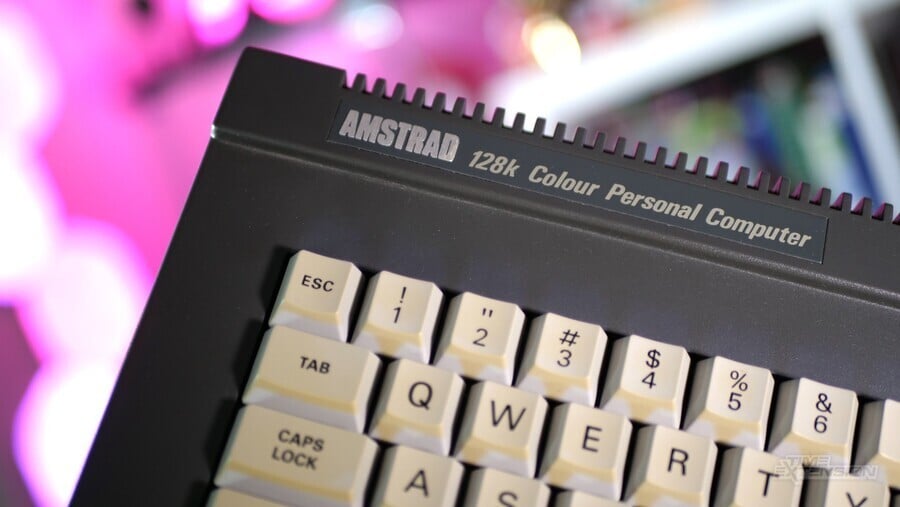

Alan Sugar’s “all in one” machine was an attractive prospect for parents looking to buy their first computer. But it found itself trapped in competition between the C64 and Spectrum, too often receiving an inferior version of a game that did well on the others. The titles that stood out are still playable and worth checking out, so here in alphabetical order are twenty that you should try.

Note: most of these titles are designed for the 64K 464/664 unless otherwise noted.

B.A.T. (Bureau des Affaires Temporelle) (Amstrad)

Live out your Blade Runner fantasies in this stylish French point & click adventure. Set in the 22nd Century, you work for the Bureau of Astral Troubleshooters, acting as a special agent in the Confederation of the Galaxies. You have just ten days to save the planet Selenia, which is being threatened with chemical weapons by the evil Vrangor. After modifying your character’s traits, you must travel between futuristic locations finding items and tracking down people. Objects and people/creatures/robots in view can be clicked on to interact with, leading to dialogue options. Buying and trading objects is essential. There is combat (shown from a first-person view, where you must avoid shooting the innocent bystanders) and a programming language for the B.O.B. computer implanted in your arm; this keeps track of your heart rate, hunger, and thirst. You can sleep as well to recover health, but that takes up precious time. There are also brief but playable spaceflight simulation sections where you are in control of a space vehicle. It was an ambitious effort for an 8-bit machine, spanning four disks. The reviews were mixed but it is worth trying for any role-playing fans.

Burnin' Rubber (Amstrad)

By releasing the Plus range of hardware in 1990, Amstrad was trying to compete with Nintendo and Sega’s consoles. The GX4000 console itself was a huge flop, but the pack-in cartridge was a cracker from Ocean. Built on the earlier excellent conversion of arcade racer W.E.C. Le Mans, the player’s sports car raced through day and night against tough time limits. First, you must qualify, and then start a series of laps with checkpoints to extend your time. The time limits get tighter, making it a great challenge to complete multiple laps (displayed visually at the end of your game on a neat little map screen). The higher colour palette and graphic resolution make this look incredibly sharp for an 8-bit machine, the palette tricks giving a convincing illusion of changing light conditions. Adding to the atmosphere are the broken-down cars and jostling opponents, all backed by excellent music and presentation. One of the best racing games across the Amstrad formats, and one that commands a high price as the supply of the rare console dwindles (there were only 30 games produced and sales of the hardware were less than 15,000 units).

Chase H.Q. (Amstrad)

This is best experienced on the 128K hardware, where you get sampled speech to bring it closer to the arcade original. Each level sees your police car chase down a vehicle, as described by Nancy in her briefing. There is a time limit to reach the fleeing bad guy, with choosing the right road at junctions being critical (an arrow or helicopter will appear to guide you). The nitro boost can be used to give an extra kick of speed, but there are many bends and hills as well as other obstacles and of course lots of traffic. Sighting the bad guy gives more time to ram his vehicle until it is severely damaged and must stop. The arcade game was tough, and the Amstrad manages to recreate the feeling of speed, keeping up the challenge – it can be tough just reaching the perp, let alone taking them down. Luckily, you can continue to play from where you have reached. It combines the fluidity of the incredible Spectrum version with good-looking full-colour graphics. As well as the speech, there are excellent sound effects and music tracks evoking the original arcade game.

Cybernoid: The Fighting Machine (Amstrad)

Raffaele Cecco was a master of the Z80, working on classic Spectrum and Amstrad titles such as Exolon (also worth playing on the CPC). Here he mixed a flick-screen maze game with a shoot ‘em up to significant effect. Your Federation fighter must infiltrate the pirate base, retrieving cargo dropped by the enemy ships. The fighter is equipped with the main cannon and five special weapons – bombs, mines, shield, bouncing bombs and heatseekers (chosen by pressing number keys 1-5 and each with a limited supply that can be topped up by collecting canisters or replenished on death). There are the orbiting mace and the tail cannon to add more firepower. Hazards include blob-firing plants, static guns, and lift shafts with moving guardians. Mastering the weapons and learning the safe spots takes time. A ticking time limit adds pressure, as does the need to collect a minimum amount of cargo to progress to the next level. The graphics are excellent, with a mixture of organic and metallic effects, and there is always plenty happening onscreen without slowdown or flicker; the massive explosions and volcano effects are particularly memorable. It’s backed by a great David Whittaker soundtrack and heaps of replayability.

Gauntlet (Amstrad)

There was much hype for the home conversions of the arcade classic, with members of Gremlin Graphics moving to Birmingham to work on the game. Although it is only possible to play with two players rather than the arcade’s four, the original choice of characters is present. Entering a dungeon level, monsters appear from generators and ghosts from piles of bones. These must be shot or tackled hand-to-hand, the latter costing health (which is constantly draining). Food and cider increase health and magic potions act like a smart bomb when used. Keys open doors and switches move walls, and the race is on to find treasure and the exit. Bonus rooms offer copious amounts of points if you collect all the treasure in time. Add-on tape The Deeper Dungeons cleverly gave an extra 512 levels to explore, including those designed by users in a competition, and US Gold followed that up with an equally impressive conversion of Gauntlet II which added more features. The Amstrad also received a port of Gauntlet III: The Final Quest, developed by US Gold and Software Creations themselves, which added four new characters and recreated the basic gameplay from an isometric perspective in 1991.

Get Dexter (Amstrad)

The French took the CPC to their hearts, and some of the top software titles emerged from French software houses. Known originally as Crafton & Xunk, the plot varies between the two versions. Crafton wants to escape to a quiet life, accompanied by the small android Xunk; he needs to collect eight parts of the security code to escape. Dexter, meanwhile, faces a war raging on Earth in 2192 AD and must protect the Central Computer by finding the door codes – helped by Scooter, a trusty Podocephalus. Whichever secondary character it is, they will follow the hero to an exit automatically and use objects to open barriers. Sensibly, the game offers a choice between rotational and directional controls, allowing the player to get used to moving in the isometric environments. Enemies drain energy on contact, which can be regained at Nurse Pods, and there are puzzles to solve to open the barriers/find the scientists with the codes you need. The detailed graphics portray the rooms of the complex nicely, all the characters are well animated, and the sound is a great accompaniment. There is a large map to explore and a sequel to try as well.

Gryzor (Amstrad)

Known as Contra or Probotector elsewhere, the start of this long-running series had some innovative ideas to bring to the run & gun genre – not least the changes of perspective and scrolling. The detailed graphics of the Amstrad interpretation mean flick-screen scrolling, but the result looks remarkably close to the original, from lush jungle to metallic base to organic alien lair. Sound and music helped push the pace, and extra weapons can be obtained from pods; that includes the iconic spread weapon. Breaking into the first base sees the action switch to the corridor third-person view, the player shooting into the screen. Tough boss encounters add to the difficulty but can be learned. The vertically scrolling waterfall level is a real highlight. Where the C64 required the use of the Space bar to jump, the Amstrad version reworked certain areas to mean control is from the joystick alone, with Fire and directions to shoot. Bob Wakelin’s cover art portrayed the heroes Lance and Bill as looking like two famous 1980s action movie stars, but there is no faking the fact that Gryzor on the Amstrad has all the playability and challenge of the arcade original.

Head Over Heels (Amstrad)

The Filmation games of Ultimate made a splash on the Amstrad, with the added colour enhancing the appearance. Jon Ritman and Bernie Drummond brought their outstanding isometric take on Batman to the format and then went one better with this game. Controlling two separate characters – Head can jump and glide, Heels can carry objects and run fast – the challenge is to escape from adjoining cells on the planet Blacktooth, combine the skills of the two and liberate planets in the Blacktooth Empire by finding the crowns. A bizarre sense of humour is portrayed through the late Bernie’s beautiful graphics. From the hooter that fires doughnuts to immobilise enemies to the Dalek-like enemies that patrol certain screens, there is immense variety here; the five different planets (and Moonbase you teleport through) each have their own background designs. Power-ups abound in the form of cuddly bunnies, and the Reincarnation Fish “remembers” your game state as a form of “quick save;” just make sure it is moving/fresh before you eat it! Head-scratching puzzles, rooms full of traps and tricky climbing sections add up to an immense challenge. It is also worth noting the excellent PCW conversion, albeit in monochrome.

Nigel Mansell's World Championship (Amstrad)

This was an extremely late release for the 8-bit machines, and never made it to the C64 at all. After an earlier game by Martech, Mansell’s 1992 Formula 1 World Championship led to Gremlin creating this new tie-in. You can go to driving school to get used to the controls, tackle a single race, or complete the whole championship. Tuning the car is important, especially selecting the right tyre for the changing weather conditions; each circuit gets a briefing telling you what the weather is going to be. In single race and season mode, you must qualify for the grid before taking on the race itself. A password system allows you to resume your progress in the season. With its low-angle first-person view, it feels like you are in the cockpit of a Formula One car. Roadside objects, bridges and signs give a feeling of speed, and the other cars look convincing up closely. With authentic circuits and real driver names, it becomes a challenge to win a race or make it through the whole championship. This is a brilliantly presented game with a solid racing engine powering it, although you will be swapping disks frequently.

Oh, Mummy! (Amstrad)

For many, the games that Amsoft bundled with their CPC will have been their first-ever computer games and will remain in their memory. One of the most memorable was this title, inspired by the arcade game Amidar. An expedition of five men is tasked with finding treasures in a pyramid, but there are mummies left behind to protect it. Explore the maze and “fill in” each tomb by surrounding it with footprints; this will then reveal a sarcophagus, treasure, key to the next level or scroll (letting you survive one hit from the patrolling mummies). But you can also reveal an extra mummy to chase you around the maze, and their randomised movements make them unpredictable. Once the player has the key and the sarcophagus has been revealed, they can leave the level via the exit at the top – or stay to find more treasure. While the graphics may now look simplistic and the music becomes repetitive, the choice of skill level and speed means it is a game you can return to repeatedly to master. It may have been converted to other machines over the years, but the Amstrad original remains iconic.

Prince of Persia (Amstrad)

Jordan Mechner’s Apple-II original gained many conversions, but this was the only other contemporary 8-bit computer version from French developers Microids. The Vizier has imprisoned the Princess and put you in jail. Now you must escape and stop his wicked scheme before time runs out. The fluid animation of the Prince came from rotoscoping, tracing over the movement of a real person. The controls allow you to tiptoe along, hang from ledges and make giant leaps as you try to grab ledges, avoid traps, and trigger pressure plates. The Prince can come to a grizzly end, being impaled on spikes or by falling too far. Finding a sword will help you fight the guards, and potions will award an extra life once drunk. This looks the part on the Amstrad, being close to the other versions. The presentation is top-notch, starting with the beautiful intro, and the animation is smooth. (The original Apple graphics were based on rotoscoping, tracing over video footage of Jordan’s brother and others moving around; they have transferred to the Amstrad well). The sound includes short jingles and effects but is effective. Most of all, the gameplay will hook you in as you try to escape.

Renegade (Amstrad)

Known as Nekketsu Kōha Kunio-kun (“Hot-Blooded Tough Guy Kunio”) in Japan, this important Technos arcade game was created by Yoshihisa Kishimoto who went on to firmly establish the genre’s foundations with Double Dragon. The Japanese setting has schoolkid Hiroshi taking on rival gangs, whereas the reworked international version Renegade drew on the 1970s film The Warriors. With the ability to kick, punch and jump, the use of combos was revolutionary in this beat ‘em up which established the formula of tackling lesser goons before taking on a boss with a large hit bar. Moving through a subway, harbour, alley, parking lot and office building, one of the more memorable moments is tackling the motorbikes. The Amstrad does an impressive job graphically of recreating the gritty look of Renegade, down to the stars rotating around a dazed opponent’s head. (A cheat unlocks the pools of blood from the arcade game). The control method does take some getting used to, but once it does the action is very satisfying and every hit has real weight. The Ocean-developed sequel Target Renegade is also worth playing but avoid the terrible Renegade III: The Final Chapter with its time-travel shenanigans.

Savage (Amstrad)

David Perry and Nick Bruty had impressed Probe with Trantor – The Last Stormtrooper, with its huge main character. They pulled off a similar trick with this game, split into three distinct segments. First, the barbarian must escape the castle. Throwing axes or other weapons to defeat hordes of enemies, the player must also pick up bonus objects for extra score and energy while jumping over pits and spikes. Large boss characters await at certain points, with onscreen messages urging you on. The second load sees Savage running in first-person 3D, heavily inspired by Space Harrier. Now you are weaving between huge pillars and shooting enemies with magic stars, trying to survive long enough to reach the next castle. The final level sees the hero transformed into an eagle, flying around another maze. Static and moving enemies abound, so be thankful you can shoot back. The graphics are superb throughout and show what the Amstrad could do. While it feels short by being split into three parts, there is a considerable challenge in making it through. David and Nick went on to greater things with Virgin and Shiny Entertainment, so it’s good to look back at their roots.

Sorcery (Amstrad)

This was a landmark early title for the format, with the updated Sorcery+ for the 6128 arriving just a few months later. In the original game, three of the four great sorcerers have been kidnapped. It is up to the remaining sorcerer to free them, by reaching Stonehenge and killing the Necromancer. To do this, the player moves between screens (using tiny doors), collecting objects and fighting enemies. The ghosts and enemy sorcerers drain your energy on contact, but it can be refilled by finding a cauldron. Weapons such as the sword will kill an enemy, and other items must be used in the right place to open barriers. There are three quest items, and the player must find the right one to defeat the Necromancer in the last of seventeen screens, Stonehenge itself. The upgraded Sorcery+ adds 38 new screens with improved graphics; these comprise an updated version of the original quest and a new second scenario to play on its completion. Pre-dating the Dizzy games, this was an impressive arcade adventure with excellent graphics for the format; it made an appearance on other machines and Sorcery+ reached 16-bit, but it was at home on the Amstrad.

Solomon's Key (Amstrad)

This was an impressive early effort by Probe, based on the unique coin-op designed by Michitaka Tsuruta for Tecmo. The sorcerer Dana must travel through the Constellations, finding a key to open the exit door on each level. Dana can make or destroy orange blocks to help him move around the level, as well as use them as barriers against the enemies (which kill on contact). Most enemies will patrol back and forth, some will home in on the player and others hug the edge of platforms/walls. Blocks can also be destroyed by hitting them twice from below. Removing blocks will also reveal hidden power-ups, which offer bonus points, extra fireballs (which travel around the edge of platforms killing enemies) and a fairy (collect these to help unlock secret levels, with 14 to discover in your quest for the Key of Solomon). The Amstrad version looks and sounds authentic, but sadly only offers 20 of the original 50 levels before looping back to the start. It does recreate many of the hidden bonuses though and scored highly in reviews at the time. The NES “prequel” Fire & Ice was also worth playing.

Spindizzy (Amstrad)

Paul Shirley’s isometric puzzle game was huge, with 386 screens to explore. Inspired by Marble Madness, the player piloted an android called GERALD, tasked with mapping the planet by visiting every screen. Movement speed and inertia are crucial as you deal with slopes and moving lifts. Bounce pads threw you into the air, ice made surfaces slippery, and switches turned features on and off to give some rudimentary puzzle solving. Falling off the platforms costs time, but more could be earned by reaching a new screen or collecting the many diamonds scattered around the levels. Helping the player see where to go was the ability to change the orientation of the screen (an arrow indicator always points North). The map screen gives a visual representation of the scale of the task, showing you where you have explored, and the end-game percentage display can make tough reading. The graphics are brilliant and give depth; the unusual option to shift between sphere, spinner and diamond may seem frivolous but can help you spot where you are standing better. There was a 16-bit sequel in the form of Spindizzy Worlds (Amiga, Atari ST, SNES and DOS) but the original stands tall.

Switchblade (Amstrad)

Core Design and designer Simon Phipps had a hit with Rick Dangerous and took a lot of the gameplay ideas forward into this manga-inspired game of exploration. As the last of the Bladeknights, Hiro must assemble the sixteen pieces of the missing Fireblade, found in the underground city, to take on the demon Havok. As you move between screens, unexplored areas are black until you enter them. Cracked blocks can be knocked away to reveal new passageways and power-ups that increase your fighting strength. Enemies and traps will drain your energy, while bonus letters earn extra lives when the words are completed. The graphic style is strong, there is a stylish intro, and the controls are responsive. The fighting mechanic (holding Fire to make a move) takes some getting used to, but there are daggers and fireballs to collect that help (although they are limited in amount). A superb Ben Daglish soundtrack adds to the atmosphere. There was also a GX4000 cartridge release, with identical gameplay but minor graphic changes to make use of the enhanced colour palette of the Plus machines, which is worth collecting. Sadly, the Amstrad and 8-bit machines never got the sequel.

Total Eclipse (Amstrad)

The Freescape engine had been developed on the Amstrad CPC first and powered a series of 3D games from Incentive, starting with Driller. This episode added an Egyptian theme with a hint of Indiana Jones, as an ancient curse is set to end the world during a total eclipse of the Sun. Exploring the pyramid, the player must find Ankhs to unlock doors and solve puzzles. And you can help yourself to some treasure along the way, shown by the dollar count at the top of the screen – along with the Moon moving towards the Sun. the ultimate time limit. Moving too much and falling will stress your beating heart, meaning you will need to rest, and your water canteen must be topped up from fountains. Fall too far and it can be fatal. There was a sequel called Sphinx Jinx, re-using the same setting as you pieced together a model of the Sphinx (which had previously appeared in the game Dark Side). The series closed with Castle Master and the 3D Construction Kit, allowing users to create their own environments and games using an icon-driven interface (with the help of a training VHS video).

Turrican (Amstrad)

Manfred Trenz did wonders with the Commodore 64 hardware in creating the two Turrican games, but there is no doubt that the Amstrad conversion of the original from Probe was impressive too. The exiled demon Morgul has returned, invading the dreams of ordinary people. Our hero dons the Turrican suit equipped with multiple weapons and the rotating lightning beam to blast his way through Morgul’s kingdom and destroy it. As well as the main gun functioning either in spread or laser fire, there are energy lines, grenades, and mines to do more damage. Turning into the gyroscope (much like Metroid’s Morph Ball) allows for speedy movement. The massive scrolling levels are filled with secrets, including diamonds, invisible blocks filled with power-ups to reveal and extra lives. And adding even more variety are the vertically scrolling jet-pack levels, as well as multiple large bosses to defeat (including level 1-2’s giant pounding fist). It’s a good job you have multiple lives and continues to get through this huge quest. Excellent graphics and sound capture the essence of the original, scrolling smoothly, and the control feels spot on.

Zap't'Balls (Amstrad)

There was an excellent conversion of arcade game Pang to GX4000 cartridge, but this was a late commercial release designed for the 6128 that plays in a similar style. There are known hardware problems meaning it does not run properly on every 6128 machine. The aim is to clear 80 screens of bouncing balls. This is done by firing a rope upwards, and when the rope hits a ball, the ball will split in half until it reaches the smallest size - where one more hit will make it disappear. Later levels add ladders to climb, bricks to destroy and much more. This well-made game offers one-player or simultaneous two-player modes and has a password system allowing you to get back to the last screen you reached. There are multiple level sets on the disk, chosen when you first load up. The Advanced Edition added five new themed worlds to conquer, each with a different graphical theme. It’s a game many people may have missed at the time but is worth checking out now.

Much like the C64 and ZX Spectrum, there continue to be new games made for the Amstrad CPC, stretching the machine, and trying new things. But these are some classic titles worth playing to experience the range and depth that it offered.

Comments 8

Some great games there but the one that really stands out is Sorcery. I first played it at my Uncle’s house, where he had painstaking created a map (with photos of each screen!) to help him finish the game.

A few years later we got a CPC 464 in our house and I was overjoyed when my Uncle came over with a box of tapes he didn’t need anymore as he’d upgraded to the 6128 - of course, Sorcery was there and I spent many more hours. Not sure I ever actually finished it, but I had a blast!

I don’t know much about the Amstrad other than it existed and was done by Alan Sugar. I had a C64 growing up, and of course I know about the ZX Spectrum and many of its games, despite never having owned or played one.

But I’m less familiar with the Amstrad, and even less so with its games, so I found this article really interesting, thank you. I must say graphically these look much better than the typical games on the C64 and ZX Spectrum. I clearly missed out!

No Roland games ?

Loved those early Amsoft games. The music from Oh Mummy still haunts me to this day

Great article! Will this site only be covering games from back in the day, or will it be covering modern homebrew titles for older platforms as well?

The Amstrad has dozens of great games from the past ten years or so...

Awww man, just looking at the cover art and screenshots is sending my nostalgia-meter into the red. My most played game on the CPC was the Amsoft Fruit Machine that came in the free bundle.

So many nostalgia fuelled memories here. Oh Mummy!, Prince of Persia, Turrican and Solomon's Key were all favourites.

Harrier Attack was also a relatively unknown favourite. Part of the Amsoft 12 pack bundle.

Fruit Machine taught me early the House always wins! I was bored of spins by the time I was pub aged.

Never quite understood Elite at the time, likely too young and it was too finickity, could never figure out how to dock/land.

Lastly Ghostbusters took about 10 minutes to load on the CPC 464 tape deck, you could die within a minute and then had to load the 10 minutes again! Gamers nowadays have no idea how easy they have it. lol

@themightyant I had Ghostbusters as part of “They Sold a Million 3” on Disc, but tape loading was a nightmare with some games

I bought one to play my fav game Rick dangerous on it, just cause I thought the picture/ graphics looked brilliant. also there was some different game play. I think there was 2500 releases for it, there was some exclusive I think. Its a computer up there with the best.I 👍😷

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...