As much as it pains us to admit it, print media is slowly coming to the end of its relevance in the video game industry. Although some pockets of resistance still exist and continue to fight the good fight, the truth is that magazines have been usurped from their position on the cutting edge by internet sites and other online portals. The printed word simply cannot compete with the web when it comes to timely news, reviews and multimedia content; in an era where people want information the moment it becomes available, video game magazines are finding it increasingly hard to stay in contention.

When a new generation like the Sega Mega Drive (known as the Genesis in the US) and Super Nintendo Entertainment System came along, clearly we needed two new magazines

To many of you, that will come as no great shock – in fact, the average gamer these days isn't old enough to recall the era when newsagents were packed with video game publications that regularly shifted hundreds of thousands of copies a month. However, it's worth remembering that prior to the online revolution, print media was the one and only way gamers could connect with their hobby; magazines were the single source of news, rumour, imagery, critique and user feedback, and when you consider the power these publications had, it's hardly surprising to find that many continue to be regarded as relics of almost holy magnitude.

One magazine which most certainly fits this bill is Super Play. Published by UK-based company Future, it made its debut back in the early '90s and, as the title suggests, was focused exclusively on the (then) shiny new Super Nintendo console. Matt Bielby was the launch editor and recalls the period vividly. "It was towards the end of ’92, and Future Publishing had been going about seven years, but it had only relatively recently become crushingly obvious that the backbone of the company was going to be single-format video game magazines of every stripe. So when a new generation like the Sega Mega Drive and Super Nintendo Entertainment System came along, clearly, we needed two new magazines. With the official licenses elsewhere, both Mega (for Sega) and Super Play (for the SNES) revelled in being 'as unofficial as reasonably possible', which resulted in a couple of quirky, individual magazines."

Bielby's previous experience was vital in securing the helm of this exciting new venture. "I'd been editor of Your Sinclair a few years before – and had recently launched Amiga Power, which had been a fair-sized hit – so I had something of a background in slightly more left-field games mags," he remembers. "Once the button was pressed, Super Play was all systems go; we only had three months to find a team, decide what this mag should be like and get our first issue out the door, so it was a race against time from day one."

Getting the magazine off the ground was far from easy, but Bielby was able to secure some significant talent. "Pretty much the entire launch team were fresh to the company, Future having completely run out of people to staff their mags at this point – it was growing so fast," he remembers.

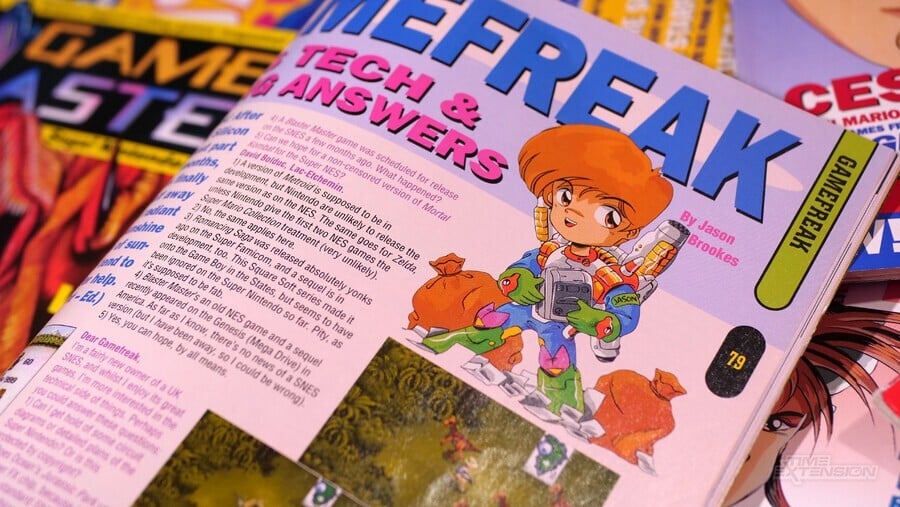

"The semi-exception was Jonathan Davies, who'd never been employed full-time at Future before, but who'd been freelance writing for Your Sinclair and others since school and was now out of university and looking for a job. He became the writing machine of the early issues, his style shaping much of the tone of the mag; it's hard to think of a more reliably entertaining writer than Jonathan. Jason Brookes was the other crucial find; he was so in love with Japanese culture, and he brought hardcore Nintendo knowledge in abundance. Whereas I'd just rung up Jonathan and offered him a job, Jason originally came in for an interview on Mega, but Neil West, that mag's launch editor, pushed him straight at me instead, saying he'd be way better for Super Play. It's hard to argue: the magazine wouldn't have been half as good as it was without Jason's telling contributions."

Jason Brookes was the other crucial find; he was so in love with Japanese culture and he brought hardcore Nintendo knowledge in abundance

The Super Play gig was precisely the break Brookes had been looking for, as it turns out. "In the late '80s, I was at Manchester Polytechnic and was pretending to be studying when, in fact, I was spending most of my time either playing Amiga games, reading games magazines or playing coin-ops like Rastan Saga and Rygar in the city’s best arcades. Around that time, I bought a PC Engine from Console Concepts and had started contributing to a fanzine called Electric Brain – a crudely assembled and photocopied rag by someone in Nottingham called Onn Lee, who, I seem to remember, had a cousin or relative in either Tokyo or Hong Kong who translated the news from Japanese mag Weekly Famitsu for him. This was way ahead of what was being reported about in the regular UK mags, so it was pretty on the ball."

Brookes would end up contributing to the fanzine, which would prove to be crucial later on – but he came close to not working at Future at all. "Funnily enough, sometime before being hired by Super Play, I had actually applied for a job at EMAP and went to London for an interview with Jaz Rignall," he recalls. "I remember he was upfront about the harsh financial realities of being a 25-year-old living in London on such a pitiful salary – fortunately, I think they ended up giving the job to Ed 'Radion Automatic' Lawrence."

Upon graduating in 1992, Brookes began work on an "incredibly dull North Manchester paper and stationery company" but quickly found his route out – and his pathway to joining the Super Play setup. "I soon spotted an ad in The Guardian looking for writers to join Future Publishing in Bath, and sent off a letter and some samples of my writing. Luckily, a publisher called Steve Carey, who was launching two new games mags, had heard of Electric Brain when I called up, and he asked me to come down and meet Neil West. Neil realised I was a massive SNES head and quickly passed me onto Matt Bielby, who was looking for another staff writer. He offered me the job the same day, which was great!"

The mag couldn't be called anything 'Nintendo' because we didn't have the license, and so 'Super' became the important word... It took some persuading to get anyone to agree to Super Play – my deliberate attempt at a sort of 'Japlish'

The speedy genesis of the magazine was demanding on the launch team, but it had benefits. "We were given pretty much a free hand, so every creative decision on the mag – from the idea to really push the Japanese thing as far as we could to finding Wil Overton to do the covers – came out of me and the team," reveals Bileby. "Good job we got most of the important stuff right, then: if we'd messed up badly, there would have been pretty much no time at all to fix it."

Still, some elements of Super Play's creation caused headaches — the name being one of them. "The mag couldn't be called anything 'Nintendo' because we didn't have the license, and so 'Super' became the important word," explains Bielby. "It took some persuading to get anyone to agree to Super Play – my deliberate attempt at a sort of 'Japlish', copying the not-quite-right English phrases that occurred throughout the Japanese magazines and Japanese culture in general. Then a number of designers struggled with the logo, not quite understanding the idea that we wanted it to look sort of Japanese and weird, until our most junior guy at the time, Jez Bridgeman, finally nailed it by putting that utterly meaningless blob thing between the U and the P. Last, we got the name translated – semi-accurately, I believe – into kanji, which was a further carry-on. I don't think I've ever gone quite that close to the wire with a logo before or since – I'm sure we weren't, but it feels like we were still designing the damn thing in press week."

Brookes admits the name didn't resonate with him initially. "I remember thinking it was a little awkward sounding, [but] I still love that logo to this day – especially now I’m a graphic designer who does that kind of design work. It was partly ripped off from Japanese New Type magazine that had a very cool logo we loved."

Right from day one, Super Play boasted a unique Eastern feel. "As with any magazine, the format of the thing comes from what you've been given to work with," explains Bielby when quizzed about why this stance was taken. "It became clear to us pretty early on that the Mega Drive was going – on the whole – to serve up an American/Western-style gaming experience, with a wide appeal in the UK, while the SNES was going to be a tad more peculiar." It was a bold move, and one that even some of the core staff were unsure of. "Introducing UK gamers to the esoteric world of Japanese cartoons was something Matt came up with," recalls Jonathan Davies. "We weren’t quite sure what he was on about to begin with, but when Wil Overton’s first cover design came in, it all suddenly made sense."

"We were very much influenced by Japanese magazines – not just games mags, but women's mags, car mags and anything else we could get our hands on too – as well as Japanese comics, anime, the whole caboodle," Bielby says. "The Super Play I had in mind from the start was, if you like, ‘mid-Pacific’, combining – I hoped – the dry English wit of the mags I'd worked on before with a loud, dizzying enthusiasm for anything Japanese. This was before the internet had arrived in any useful form, remember, and still a time when the only anime most folk had ever heard of was Akira; with nobody else really pushing the Japanese angle at all, we suddenly found we had this whole fascinating, largely-unknown culture to explore more or less by ourselves."

The Super Play I had in mind from the start was, if you like, ‘mid-Pacific’, combining – I hoped – the dry English wit of the mags I'd worked on before with a loud, dizzying enthusiasm for anything Japanese

Super Play's adoration of Japanese culture culminated in its extensive coverage of Japanese animation, or 'Anime' for short. It was a logical progression. "With the Japanese theme kind of established, we needed material to fill Super Play, and one crucial find I'd recently made was a little independent-mag-cum-fanzine called Anime UK, tucked away in some dark corner of comic retailer Forbidden Planet," states Bielby. "That's where I found both Helen McCarthy, who became our anime expert, and cover artist Wil Overton, whose fabulous anime-style art – I'm sure there was no one else in the country who came close to him at the time – became such a memorable part of the magazine. I couldn't begin to claim Super Play introduced anime to a UK audience as such, but thanks to guys like these, I think we did our bit to popularise it."

Another critical component in the magazine's success was its mix of expert advice and side-splitting humour, which Brookes credits to Bielby and Davies. "The tone was set by Matt and Jonathan really, and it made me appreciate how much talent goes into making a magazine a good read, and in Super Play’s case, in particular, a great place to feel included in something exciting. Looking back through the early issues recently, I realised that it must have been so much work for those two since their output in terms of words was so much higher than what I was capable of – I remember the first month or two of the mag was a slightly wobbly time for me confidence-wise because most of the ‘hilarious’ reviews I did were either changed a lot or substantially toned down by Matt. But gradually, I understood that there needed to be an overall style and tone that we worked to collectively – warm, friendly and amusing, if possible. Jonathan constantly nailed it, and was a little envious of his dry wit and writing ability."

Wil Overton's distinctive cover art is unquestionably one of the reasons that Super Play stood out on newsstands back in the early '90s and why it's remembered so fondly today. "These days, every games magazine runs a glorious piece of game art on the cover, often created exclusively for the magazine by the development team," explains Beilby. "Back then, that simply didn't happen, and games mags would commission artists to do their own version: a risky/exciting business, no matter how talented the artist. I'm sure Wil's style brought a few confused and perhaps concerned looks at Future's boardroom level in the early days, but it wasn't long before everyone bought into what I thought self-evident: he was very much the best — and perhaps, at the time, the only — man for the job."

I ended up doing all the captions myself so that they were factually correct rather than just variations on ‘Ha! Those wacky Japanese’ and then got told that I couldn’t just do that stuff myself and had to change them back

Overton would eventually join the Super Play team as a staff writer and illustrated each and every one of the magazine's 47 (well, 48 technically, but more on that later) covers with exclusive artwork. His involvement with Super Play was largely due to this anime background. "As I was doing the covers for Anime UK at the time, Matt asked if I’d be interested in doing the cover to the first Super Play," he fondly recalls. "Surprisingly, he came back and asked me to do issue two, and from then, we were off! Things had moved on a little by the time I was asked if I would be interested in joining the team. At that point, I had moved to working from home as a freelancer, doing various bits of artwork, but the idea of working on a mag that combined games — I was still knee-deep in and obsessed with Super Famicom imports at the time — and anime was too good to pass up. I went down to Bath, had a chat and a few weeks later was offered a job on Super Play."

Overton's commitment to the magazine's cover artwork meant that he was producing mini-masterpieces on a monthly basis — a demanding schedule for any artist. "It was more of a physical challenge once I had joined the team full-time," he explains. "I don’t know whether Matt had any grand plan that I would do the covers every month or whether it just ended up like that, but I do think it helped make the magazine stand out. There aren’t many ‘angles’ a video games mag can take (from both a visual and editorial standpoint) to make itself distinct, but I think Super Play hit on a good one. I guess you could argue that the more specialist you make a mag, the more you limit its audience, but I think Super Play managed that fine line between the niche Japanese stuff and still having all the normal games mag contents, too."

Overton was (and still is) an avid gamer, and he readily admits that his love of games manifested itself in somewhat awkward ways. "I do remember laying out an import review of Ganbare Goemon 2 by Jon Smith (later Lego supremo at Traveller’s Tales) and basically being annoyed that it didn’t appreciate where all the references in the game came from and the history of the character. I ended up doing all the captions myself so that they were factually correct rather than just variations on ‘Ha! Those wacky Japanese’ and then got told that I couldn’t just do that stuff myself and had to change them back."

As well as championing Japanese culture in all its shapes and forms, Super Play was arguably the first place many UK gamers were exposed to SNES JRPG classics such as Final Fantasy and Secret of Mana; the genre had, by and large, been unfairly ignored by other publications. Tackling Japanese role-playing games — as well as other import releases — naturally fitted in with the theme of the magazine, but there were more practical reasons for the extensive import coverage.

I was fascinated by what was happening in Japan and really wanted to be part of a magazine that communicated that excitement... I was obsessed with the SFC and Japan and came with a lot of knowledge and enthusiasm to skew things that way as much as possible

"There were only going to be six or so officially released games for us to review each issue – as opposed to a dozen or so coming into the country as grey import – and we quickly decided we might as well play to our strengths," says Bielby. "The big issue was to fill the magazine, and if there were only ten games out one month, then nobody was going to moan at a one-page review of anything, even if it was some utterly baffling strategy game from Sunsoft or Enix, heaving with near-untranslatable Japanese text. It was all part of the magazine's mad mix, part of what made us different – and part of the appeal of the SNES too. Even if the average Super Play reader was never going to buy Super Wagan Island or Zan II, the fact that it existed and we could tell people about it added to the unique feel of the magazine."

Again, Brookes became an integral part of this import-centric content strategy. "Personally, I was fascinated by what was happening in Japan and really wanted to be part of a magazine that communicated that excitement," he says. "So Matt's idea for a Japanese-styled SNES mag was a dream come true in many regards. Matt and I saw eye-to-eye on the heavy Japanese slant, although with me, he probably got a lot more than he bargained for! I was obsessed with the SFC and Japan and came with a lot of knowledge and enthusiasm to skew things that way as much as possible. As well as our Japanese features and previews, the ‘What Cart’ section was something I was quite proud of in this regard – you really got a sense that there were all these weird Japanese games out there in the SNES catalogue that you would probably never get to play, but were glad they existed anyway."

The magazine's intense focus on the Far East also helped Super Play seem cutting edge when compared to its competitors, covering games that wouldn't see the light of day in the West until much later. "These were the days when it could take months, or even years, for a game to make it over from Japan to Europe via official channels – if it ever made it at all – and the slow-motion, 50Hz PAL conversion tended to be a pale shadow of the NTSC original," adds Davies. "So a true SNES fan sought solace in playing imported games on an imported console — or via a UK console and one of those wobbly adapters."

Given the niche nature of the games Super Play was covering (and putting on the cover, no less), one would assume that some degree of friction existed between the editorial staff and Future Publishing. Thankfully, this wasn't the case. "I don’t think there was ever a time when we didn’t have the full backing of our publisher," says James Leach, the man who succeeded Bielby as editor of the magazine in October 1993. "We did discuss whether to feature some of the most esoteric RPGs, but the consensus was always that we should. Part of the mag’s remit was to really delve into the Japanese games world, rather than just pick and choose from the more accessible games. It’s a bit like car magazines reviewing Aston Martins. People want to read about them, even if they aren’t going to be buying them."

Getting reliable info on Japanese games became a painful, time-consuming business, involving late-night phone calls to the other side of the world, local language students doing half-arsed translations for us from Japanese magazine articles, and all sorts of palaver

Covering exciting import titles wasn't all plain sailing, however. "Getting reliable info on Japanese games became a painful, time-consuming business, involving late-night phone calls to the other side of the world, local language students doing half-arsed translations for us from Japanese magazine articles, and all sorts of palaver," winces Bielby. "In some ways, the magazine doesn't look too impressive now, but just thinking of the hoops we used to have to jump through to get anything to fill the thing at all still sends me into a cold sweat."

Brookes feels he may have added to Bielby's woes thanks to his desire to fill the mag with cutting-edge info from Japan. "Within a few issues, we hired a local Japanese speaker to translate games mags we used to order from The Japan Centre in London. And I remember always pushing for us to order expensive ‘repro’ scans of screenshots from Japanese mags of newly-announced games when we were on deadline – I probably drove the art staff slightly crazy, but our timing was often good, and we did frequently get good scoops!"

There were headaches for the reviewers, too. "Back then, you hadn’t lived till you’d battled against hordes of fire-breathing mutant super-demons from the year 2026, entirely in Japanese, without having a clue what was going on, knowing that your review had to be handed in the next day or you’d be answering to fire-breathing production editor," laments Davies with a wry smile.

Super Play quickly established itself as one of the UK's finest video games publications and rose above the competition. However, as Leach admits, rival magazines such as Super Control and Nintendo Magazine System helped keep the Super Play team on its toes. "We respected other mags, and sometimes they ran features or reviewed stuff we didn’t know about," he reveals. "One thing nobody likes is to be copied, though, and we did get miffed on the occasions when others pinched our style and ideas. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, but it caused a few Gundam models to be thrown across rooms in annoyance."

Then one day, I was marched into an office and ordered to edit Super Play. It was arguably the coolest mag Future published, and had a great team. I was therefore delighted and danced a sort of Spice Girls-y jig later than evening

Naturally, during the course of a magazine's history, staff changes are inevitable; Brookes departed after issue nine, joining EDGE magazine and eventually becoming its editor until issue 50. "My passion was ultimately multi-format gaming, and I always had a keen eye on what was coming next," he says. "EDGE was a very lucky streak for me – Steve Jarratt moved off after just nine issues, and I got to take the top job. Kind of ridiculous when I think about it – I was so inexperienced." Bielby was next; he vacated the editor's seat after 12 issues to move into other projects. "I loved and enjoyed Super Play," he says. "It was time to move on. Anyway, I left it in safe hands." As we've already mentioned, those safe hands belonged to none other than James Leach, already something of a veteran at Future by this point.

"I’d been working as Deputy Editor on GamesMaster since it launched," Leach explains. "The magazine covered all the major games platforms, so I’d kept my beady eye on the SNES world during my time there. Then one day, I was marched into an office and ordered to edit Super Play. It was arguably the coolest mag Future published and had a great team. I was therefore delighted and danced a sort of Spice Girls-y jig later than evening."

Leach would edit the magazine until issue 30, when Super Play's third (and final) boss took over. Alison Harper's reign would last for another seventeen issues, and during all that time, the quality of the publication never faltered once. Sadly, all good things must come to an end, and by the middle of the '90s, it was clear to even the most stubborn Nintendo fanatic that the SNES was on borrowed time. The N64 (then known as the Ultra 64) was looming on the horizon, and the effect on Super Play's long-term chances was predictably dire.

Many key staff members had moved on by this point in time, and Overton recalls the day he had to vacate his desk. "I didn’t want to move, but Super Play was coming to a natural end," he says. "I guess you could see it in the releases the UK was getting and the lack of stuff on the horizon, so, despite me trying to last it out until we could transition it to the N64, the powers that be moved me off to GamesMaster magazine – which, in reality, was just upstairs in the same building. It was a good team, but I didn’t have any interest in it, and fortunately, in the end, it was just a stop-gap before N64 Magazine came along. In hindsight, it was probably the best thing. N64 was able to start anew and make its own identity." Indeed, many hardcore Super Play fans consider the magazine that accompanied Nintendo's 64-bit console to be the spiritual successor to Super Play – but that's another story entirely.

Super Play is thought of fondly because the writing was great and what came over was that we really did love the games we covered

Like so many magazines of the era, Super Play was a breeding ground of industry talent, and many of its former staffers can now be found in high places. Overton would go on to work at UK studio Rare, and Davies is in charge at the highly respected video game PR resource site Games Press. Beilby has enjoyed an incredibly productive career, too. "I left Super Play to launch PC Gamer, then went to the US to do the American version of that, then came back to launch .net magazine and UK sci-fi publication SFX. As you might have guessed, launching magazines is one of my things."

Although it seems like a trite question to ask at the conclusion of a feature which (hopefully) has explained the magazine's intrinsic appeal, we have to ask: why is Super Play so fondly remembered today? "I like to think that while Helen’s Anime World and stuff like the RPG Fantasy Quest pages gave an insight into a games world that no other UK games were covering at that time, Super Play is thought of fondly because the writing was great and what came over was that we really did love the games we covered," replies Overton.

"Super Play didn’t try to be all things to all people," adds Leach. "The more specifically you target an audience, the happier that audience is. However, the audience needs to be big enough to sustain you. Luckily we had enough people who liked us and wanted us to be different and weird and cover odd Japanese stuff which nobody outside the country had ever heard of. I think people liked that quirkiness. Plus, it looked distinctive and different, too. There was a lot of white on the pages at a time when most mags were garishly printed on full-colour backgrounds. And also, there were some very humorous writers working on it – I’d like to think that people remember Super Play as being funny, too. Certainly, it was meant to be."

"I think what made it unique is what makes so many of the best magazines unique: they do more than was expected of them, pursue interesting avenues other magazines might not think of, provide an individual rather than generic take on whatever it is they're writing about," says Bielby. "With Super Play, in particular, I think it was that whole Japanese thing that made it, the excitement of this weird and wonderful new culture we were writing about. Today, Japan can still feel a bit odd, but anime, the internet and generations of Japanese games mean that when you visit there, a lot of it is surprisingly familiar. Back in 1993, not so much. I think that's where we got lucky with Super Play."

I would imagine it felt like you had joined up with an extended bunch of friends who also felt as excited about the future of the console as you did

Super Play's position as a legendary '90s video game magazine is all but assured, but in 2017, publisher Future gave it a one-off revival which only served to reinforce its brilliance. Edited by Tony Mott (a long-time Future Publishing editor who has worked on EDGE for many years) and including the talents of Overton, Brookes and Davies, the 52-page mini-issue was given away free with Retro Gamer magazine and focused its attention mainly on the then-new SNES Classic micro-console. "It turned out great, and I really enjoyed contributing to it," says Brookes. "Wil’s Star Fox 2 cover looked fantastic, I thought. Also, the fact that it was bundled with Retro Gamer, which had a PC Engine feature cover feature, was the cherry on a long-overdue cake."

Sadly, in 2019, after the original publication of this piece, Jason Brookes passed away following a long battle with cancer at the age of 52. We'd like to dedicate this feature to his memory. We'll also allow him to have the final word. "When you bought the console and then perhaps subscribed to the mag, I would imagine it felt like you had joined up with an extended bunch of friends who also felt as excited about the future of the console as you did. We had a basic plan to create a cool, personality-driven games mag for the SNES with a heavy Japanese angle. Matt and Jonathan knew about writing and magazines in a way I really didn’t, but I knew the Super Famicom's upcoming Japanese release schedule like the back of my hand, and so it was a good pooling of skills that resulted in a winning combination: hardcore, authoritative reporting with a strong, personality-driven tone."