The term "labour of love" is often bandied around in media circles, usually relating to a personally important project by an artist writer, and while it's possibly overused in some cases, it most certainly applies to John Szczepaniak's quest to chart the hitherto unseen history of the Japanese game development community.

It all began when Szczepaniak - an established video game journalist with years of experience to his name - decided to launch a Kickstarter campaign to raise the required funds to travel to Japan, interview some of the unsung heroes of the development community, translate their words, take photos and generally cover the cost of putting together a book and accompanying DVD. The goal of £50,000 seemed outlandish, but Szczepaniak silenced his doubters by eventually raising over £70,000. Volume 1 of The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers arrived last year, and proved to be a complete and utter joy to read and digest. However, as its title suggested, it was merely the beginning; Szczepaniak had collected so much material that further volumes were required. We've finally gotten our hands on Volume 2, and it's a bittersweet experience - for reasons we'll go into shortly.

As with the previous edition, the book is made up of interviews with various Japanese game developers, most of whom will only be familiar to truly dedicated followers of gaming. Some of the interviews are with individuals, while others pull together multiple participants who served at the same company, giving a fuller picture of how each firm operated. For example, there's a lengthy section on Wonder Boy studio Westone Entertainment, with input from founder Ryuichi Nishizawa. The origins of Hudson Soft are covered in another chapter, and names such as Irem, Masaya, Falcom, NCS, Human, T&E Soft and others also appear. If you were an active import gamer during the 8 and 16-bit eras, then those firms - and the games they produced - should spring to mind quite readily.

The highlight of Volume 2 has to be the opening chapter, in which Szczepaniak interviews a series of anonymous developers under the catch-all pseudonym Hideo Nanashi. Some of the details in this chapter are so legally volatile that company names have been blanked out, and as you might expect, it's absolutely essential reading. Another shocking chapter concerns the founder of Zainsoft (also known as Xian Soft and Sein at points in its history), Takahiro Miyamoto, who is described by former employee Kensuke Takahashi as a "psychopath":

One time I kept working for nine days without any sleep. And then Miyamoto-san spotted me dozing off, and he came up behind me and kicked me as hard as he could. The desk and and myself went flying two or three meters, but I was so tired the pain didn't even register. I hit my head against the monitor hard enough to make the screen crack. But the only thing I cared about was whether the computer was working or not.

Each and every page is dripping with amazing facts and information, as well as jaw-dropping anecdotes - like the one quoted above - that could only have been unearthed during an informal, face-to-face interview. Some may have balked at Szczepaniak's insistence on actually travelling to Japan in order to speak with the developers - especially in the age of email and Skype - but by going the extra mile he has secured insight which would most likely have been lost if that human connection hadn't been made. For that, the author deserves our unreserved gratitude, as these stories might never have been told in Japanese were it not for his efforts, let alone translated into English.

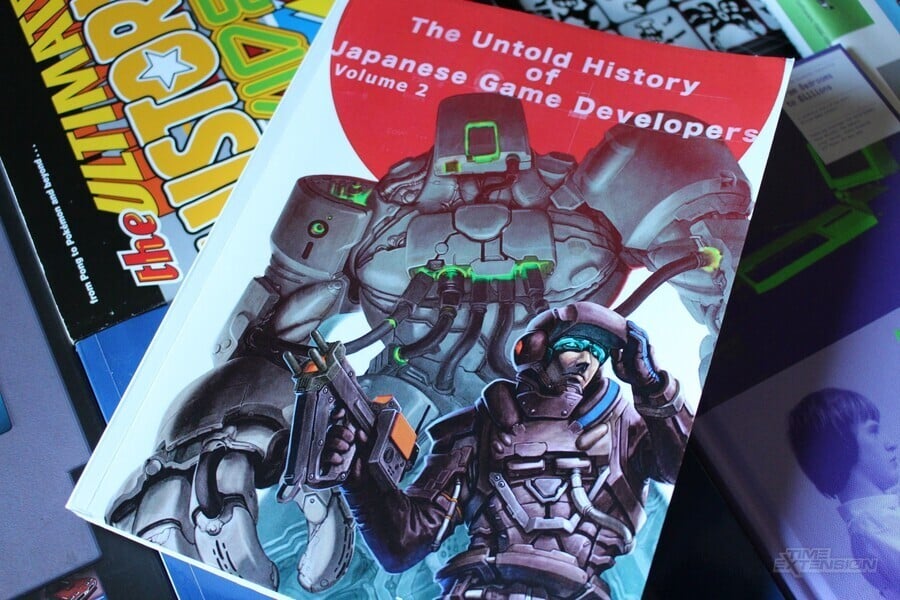

The book is bursting with amazing content, including concept art, photos and other images which adorn each page, as well as a cover image exclusively illustrated by Satoshi Nakai, who worked on such titles as Cybernator, Front Mission: Gun Hazard and Gynoug. The use of imagery is more creative than it was in Volume 1 - Szczepaniak notes in his introduction that he has deliberately "abandoned stylistic consistency" because each interview subject is different. Rather than create chaos, this shift has resulted in a situation where each page has something to catch the eye and draw the reader in. Even in the monochrome edition - which we reviewed - the mixture of text and image is enticing, and an improvement over the occasionally sparse nature of the previous volume.

Now we come to the bittersweet element mentioned earlier. Volume 1 teased us with multiple "coming in the next volume" pages detailing the contents of future editions, and Volume 2 does the same - only this time around, we might not actually get to read these mooted interviews. In his intro, Szczepaniak reveals that despite his amazing efforts, sales of the first book were poor:

I fear that the intensity of my love for Japanese games caused me to incorrectly assume there must be a sufficient number of people who felt the same, thereby making these books a viable proposition.

He then goes on to beg the reader to spread the word and tell as many people as possible about the book and its predecessor. Volume 2, he asserts, cost more to make and took more time to produce than the first book, and Volume 3 can only be made if sales pick up. All of the cash raised from the sales of Volume 1 and the supplementary DVD were put into the production of this book, along with some of Szczepaniak's own money - from savings and loans. It would be a crying shame if his quest to document the history of Japan's vibrant and influential games development community ended here, so we entreat you to make a purchase - if you have even the most cursory interest in games from the Far East, then both of these books are essential reading.

The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Volume 2 is available now from Amazon in both the US and UK. A full-colour edition is available from CreateSpace.

This article was originally published by nintendolife.com on Wed 25th November, 2015.

Comments 21

I'm aspiring to be a game designer, so I'll probably grab one (or all) of these books to see what that life can be like.

@kyuubikid213 Not a lot of sleep or pay, not much of a life. You're going to be searching for new jobs A LOT.

Would love to give this a read, it's just not in my price range. Is there a cheaper digital version?

I think the reason people didn't buy Volume 1 was due to the ridiculous controversy that surrounded Szczepaniak at the time. Nobody wanted to cover the book and so word of how magnificent it was didn't get out... the controversy also tainted the book's content and by extension the contrent of Volume 2 and 3...

I really feel for Szczepaniak, I absolutely love Volume 1 and cannot wait to get my hands on this one day, I just hope that his unique research finds its right audience one day.

@Humphries90 Volume 1 could be had in Kindle form, perhaps this will one day be on too. The physical copies are well worth it though, absolutely bursting at the seams with content... 400 pages worth of small print for £25 is a bargain! The first volume has over 500 pages if you want even more bang for your buck.

@davidevoid You mean regarding the translators?

Ouch, the price is a little steep. But interesting read on here!

My eyes scanned Miyamoto in the quote before reading the preceding sentence...I was disturbed for a second.

I know it's not appropriate to find it amusing, but the image of someone in a chair flying several feet along with the desk and head butting a computer seems pretty comical in a cartoon sort of way. Especially after reading the victims response about only being worried for the computer

I've only dipped into volume one - I've had it since last Christmas - but i feel qualified enough to say it's fantastic. If the second volume is more of the same then frankly it's worth your time and the money.

The author is knowledgable, the interviews frank and revealing. Even games you never knew are fantastic to read about. I hope people pick this up. Volume one is a mammoth tome, it offers value for money and it's very thorough. You'll be reading it for ages but it remains interesting throughout.

Am I the only one who's bullsh*t detector went off while reading that excerpt about Miyamoto? First of all, if you went nine days without sleep, you would likely be unable to concentrate on menial tasks like tying your shoes or remembering to stop at a red light, let alone complex programming or whatever the guy was doing. There's no way anyone's building a video game with nine days of no sleep.

And really? Miyamoto kicked him so hard that both he and his desk went 6-9 feet across the room? So then after the guy's head cracked his monitor, did Miyamoto use his laser gaze to fuse the glass back together, and then put on a cape before flying off to fight Lex Luthor?

@CHET_SWINGLINE That's Takahiro Myamoto, not Shigeru Miyamoto. The point was that game development has absolutely no regulations, unions, or anything to ensure fairness in the workplace, which has sometimes led to instances of vile misconduct in the workplace.

@CHET_SWINGLINE You need to read the rest of the chapter, plus comments from another Zainsoft employee in Volume 1 - it's clear that this guy was a complete headcase and could get away with what he wanted because it was a family-run business.

@Damo exactly, it seems to have gotten totally out of control and he now blames it as the main reason the first volume didn't sell as well as he would have expected. There was also some ludicrous controversy over the cover for the 'Platinum' version of Volume 1.

@davidevoid Sounds like the translators themselves were complete nutjobs. Hopefully this second volume can help stir a bit of interest in the first. These are seriously two of the best books about gaming I've ever read.

@Damo Agreed, the first Volume is an impressive and incredibly niche read, an important one too as it helps archive information that could have been lost to the ether. Good on you guys for showing it some love!

Do you plan on getting HG101's 200 Best Games in for review? Love their output; very honest and enthusiastic... quite like Nintendolife!

I'm currently reading my copy of Volume 2, brilliant stuff. Proud to be a backer of this Kickstarter.

@PlywoodStick Umm yes I know. Where did I say that I thought it was Shigeru Miyamoto? I wish it was about him though, that would be a hilarious counter to his overt friendliness and positivity.

@Damo I never said I didn't believe the guy was a maniac, I said I have a hard time believing that A) a person can go nine days "without any sleep" and still be able to function in any meaningful way, B) a man exists who can kick another man, along with his chair, desk, and workstation (all of which probably weigh a minimum of a couple hundred pounds) with such force that they fly 2-3 meters across the room (even if this took place on an ice skating rink you'd have a hard time pulling this off), and C) that a guy was kicked from behind with the force of a full team of Clydesdales, and yet instead of his head whipping backwards like you'd expect, it flew forward and smashed into his computer that was also traveling forward, and resulted in what I'm assuming is an old monitor with a thick glass screen being cracked through, and yet the guy didn't suffer a massive concussion and pass out.

I'm not trying to rain on anyone's parade, and the book seems like a fun read, I just find these particular details to be a little hard to swallow.

@CHET_SWINGLINE lol, I spent too much time after reading it trying to figure out how it's even possible

sounds like a really interesting book to read. I really dig the aesthetic of japanese games during the eighties and nineties. I really wanna get vol. 1 & 2 now. I have a great appreciation for Cybernator and the studio that created it

@Blastcorp64 Right? I'm just amazed that more people weren't left scratching their heads at the physics of that story.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...