As part of our end-of-year celebrations, we're digging into the archives to pick out some of the best Time Extension content from the past year. You can check out our other republished content here. Enjoy!

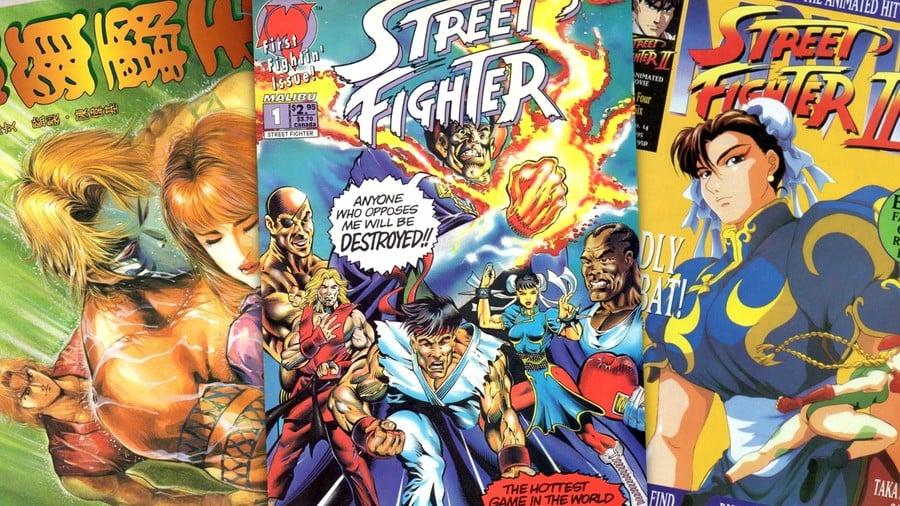

A global phenomenon, revitalising arcades and dominating home systems, Street Fighter II defined gaming. Merchandising followed, with enough SFII branded tat to rival even Mario or Sonic, but what's especially interesting is how multiple countries created official Capcom-approved comic adaptations – and each one was totally distinct.

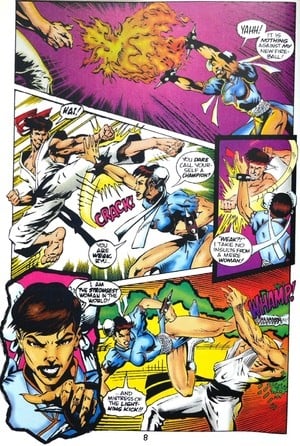

My first encounter with Street Fighter comics was in South Africa, reading the May 1993 issue of Electronic Gaming Monthly. It contained the second of a two-part excerpt from the launch issue of the Malibu adaptation, and though just six pages it massively caught my interest. The excerpt showed Ryu and Chun-Li sparring and then kissing – a revelation which was mind-blowing! While today there is a well-established canon for various game storylines, at that time not much was defined outside of the games themselves.

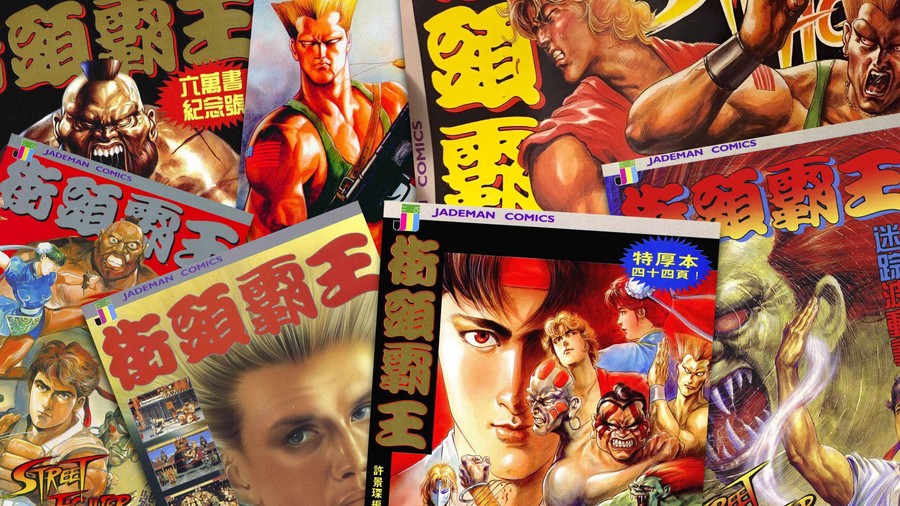

Even more mind-blowing was when a close friend pointed out this wasn't the true comic. A friend of his, whose father ran a Hong Kong import business, had stacks of outlandishly awesome Street Fighter comics unlike anything we'd ever seen before, in a language we couldn't read. At the time I assumed these were Japanese, but in fact, it was the fabled Jademan adaptation from Hong Kong, which started in 1991 and ran to over 113 issues. Further complicating matters was the fact that British magazines at the time ran news pieces on the Japanese manga created by Masaomi Kanzaki and published by Tokuma Shoten.

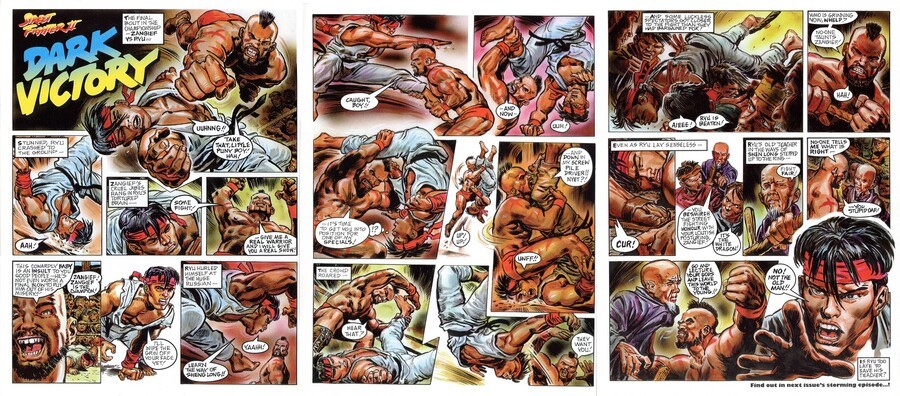

A couple of years later, having emigrated to the UK, I was able to collect the official English release of the eight-part Tokuma series. This was followed by a two-part comic adaptation of the live-action movie, which starred Jean-Claude Van Damme, and was then followed by a loose six-part adaptation of the anime movie. There were a lot of Street Fighter comics available in the early 1990s, and this doesn't even include the unique series exclusive to Brazil, the unreleased UK series by Oliver Frey, or the newer iterations which followed. All of these were officially licensed, too. When examining the world of Street Fighter, its video game, comic, and anime stories are all different, and Capcom officially endorsed multiple separate timelines (canonical or not).

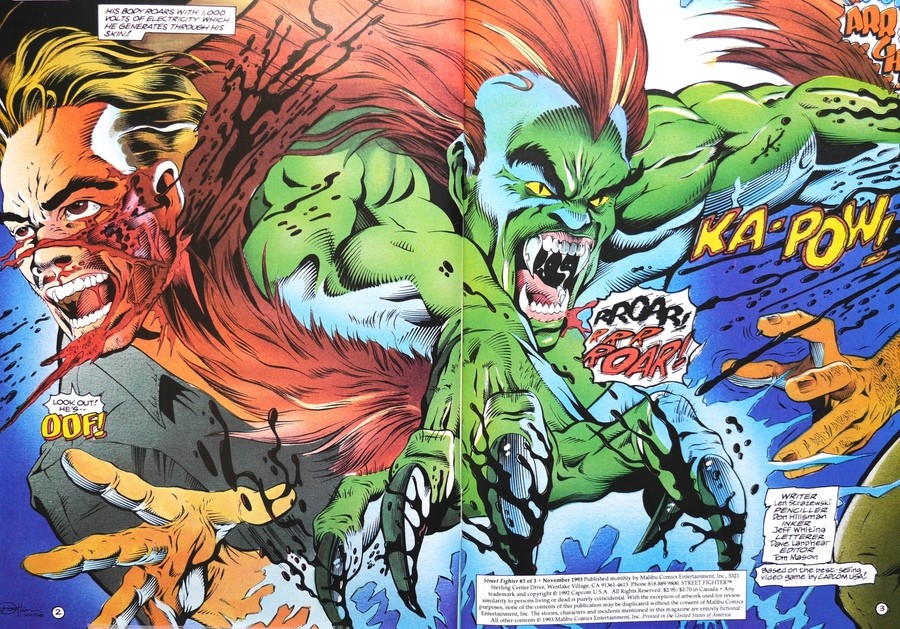

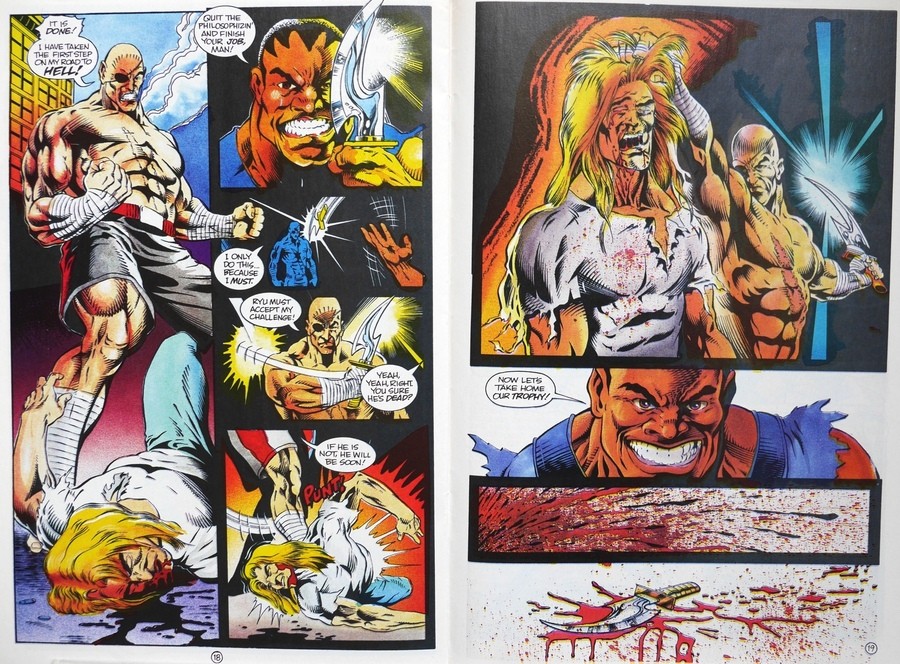

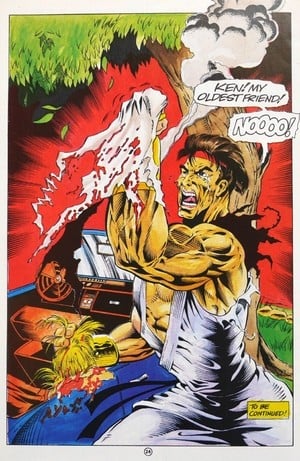

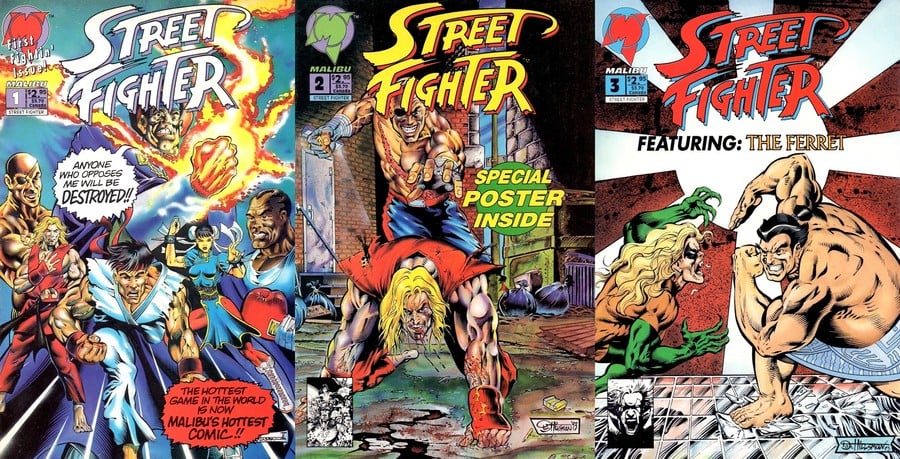

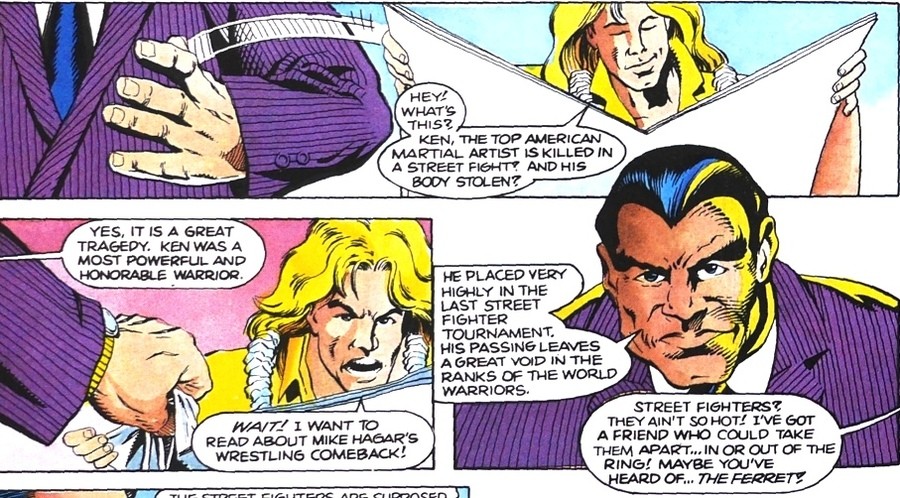

Fast forward to the present day, and it would appear very few have attempted to document the bizarre and eclectic global range of comics based on the Street Fighter brand. So I started some research, focusing on the US-produced Malibu series, which lasted for just three issues. This series is imaginative to say the least. It contains all the characters – even Sheng Long – and Ken is murdered by Sagat in issue 2 (but he's not really dead). Ryu and Chun-Li are lovers, there's a crossover fight between E. Honda and Malibu superhero The Ferret, while later issues would have involved clones. Reading issue 3's epilogue provides more nuggets of narrative gold, including that Ken taught "Blanca" (sic) to read; the epilogue also offered the only official explanation for the publication's short run, stating there were complications due to Capcom disliking the adaptation; it concludes by giving Capcom USA's address, should readers want it.

Although today it's easy to dismiss the Malibu trilogy, especially given the now tighter control companies have over their brands, the story is entertaining enough and does an admirable job adapting what was basically just 12 people kicking the crap out of each other against backdrops stolen from movies. To gain a little more insight into its production, I spoke to two of the key creative figures involved with the series.

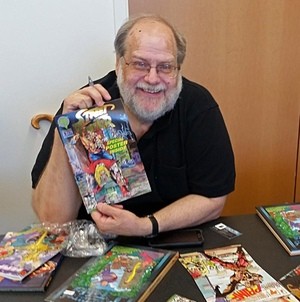

Tom Mason (Creative Director, Malibu Street Fighter Series)

Mason has enjoyed an extensive media career, to say the least. He co-founded Malibu Comics in 1986, was later a vice-president at Marvel Comics, and went on to write scripts for TV including Malcolm in the Middle and Rugrats. He also created the Dinosaurs for Hire comic and Sega Genesis video game. Mason served as creative director on the Malibu Street Fighter series.

Did Malibu approach Capcom, or was it vice versa? Was it an expensive license to acquire?

Tom Mason: I'm not at all sure anymore. I think it came through Scott Rosenberg, Malibu's President. He would've set the ball in motion if they'd contacted us or we'd contacted them. I wasn't involved in the money or negotiations either – that was all Scott.

Who were the main points of contact at Malibu and Capcom?

TM: Scott [Rosenberg] for business matters and me for editorial matters. Laurie Thornton was my main contact at Capcom USA.

Did you meet with the game's Japanese creators?

TM: No. Just some of the staff in northern California and they were mostly licensing people.

What were the meetings with Capcom like?

TM: There was only one meeting that I was a part of – when [editor-in-chief] Chris Ulm, Len Strazewski, and myself flew up to Capcom to meet with the people in their office and discuss plans for the comic book series. We met with about a half-dozen of their people and sat around a big conference table, tossing out ideas about story, characters, tone, direction, and so on. All the usual stuff that goes on in a big creative summit. It was all very fun and creative. It was several hours and it was very creative, very convivial with a lot of back and forth about what would work and what wouldn't.

Did Capcom stipulate any restrictions or requirements? What was their approval process? Did they say "no" to any ideas?

TM: I'm sure they did, but I didn't keep my notes of the meeting. But it was a creative meeting so any "no" that got tossed out was just a normal part of the process. The meetings were not at all antagonistic, and it wasn't a negative back-and-forth argument – just part of the creative process to bring a book together, finding out what we could and could not do, how the characters related, what the backstory was, and so on.

What materials were provided?

TM: We got copies of all the reference material that was available at the time without any hesitation. And anything we needed, we could just ask for and it would be provided. I don't remember exactly what it all was, but it was a huge pile of stuff including an arcade Street Fighter II game. And new stuff would arrive at my office as Capcom approved what I could see and share with the creative team. Malibu Comics had inter-office email since 1990, but in 1992, actual email was still not viable. It was all phone, fax and face-to-face, plus FedEx.

How were things organised between yourself, writer Len Strazewski and artists Don Hillsman and Jeff Whiting? What was the approval process at Malibu?

TM: Before working on Street Fighter, we – and specifically me – had already worked with Harmony Gold on Robotech, 20th Century Fox on Alien Nation and Planet of the Apes, and Paramount on Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, so this wasn't new territory for us.

Here's the way all licensed comic books work. Before anything goes forward, each stage has to be approved by the licensor. They sign-off on premises, outlines and scripts before it goes to the artist. They then sign-off on the pencils, then the inks, then the colours, and the covers, and the lettering. Everything passes through their hands for a sign-off. As each step is approved, it passes from writer to penciller to inker to letterer to colourist, with me at the centre of it.

Issue #1 says work began July 1992; it's dated August 1993. Did it take one full year to bring to fruition? That seems a long time – was there an inkling of dissatisfaction from Capcom?

TM: It would be wrong to assume that the length of time is an indication of problems or the beginning of any dissatisfaction, if that's what you're getting at. There was no antagonism between the companies during the pre-production process. A lot goes into preparing a licensed book from closing the deal, to signing the creative team, to getting the material moving forward.

For the direct market, an August book is due to be solicited from the distributors around early April, so production has to be rolling well before then. An issue generally takes 30 days to write, 30 days to pencil, 30 days to ink, and 14 days to colour, with approvals all along the way. And you want an issue or two in the can before you solicit, so whereas you're seeing a long time, it's really the right amount of time to get anything done correctly. Plus Malibu published a lot of books each month and it's always critical to try to find the right month to launch a new #1 – and I think we held off on soliciting Street Fighter #1 so that it could debut around the time of that year's San Diego Comic-Con, where our booth would also have the arcade Street Fighter II game.

That was the way we worked with everyone and Capcom was no exception. They may have wanted story points corrected or clarified, dialogue fixed or characters swapped out, or art reworked here and there, but again that's normal and within the right of any IP owner and wasn't anything that impacted the release schedule.

Adapting a videogame into a different medium like film or comics is notoriously difficult. What was your biggest challenge?

TM: The biggest challenge is always identifying the characters and figuring out the story. There's a backstory to Street Fighter II, but it's not really a dramatic story, so it's about coming up with a narrative that can support the characters. I had read a DC comic that Len did called Justice Society of America that was a great take on a team book, and that impressed me enough to ask him to write Street Fighter.

What was Capcom's reaction seeing the first completed issue?

TM: Capcom had seen each stage of production, from start to finish, and approved it at each stage, so the completed first issue was not a surprise to anyone.

Work on the launch issue started July 1992. In it Chun Li uses her new fireball. This new in-game move was introduced after the comic started production. How did you know she'd receive it?

TM: We didn't have any foresight. Capcom told us in advance. Since games take a long time to make, it doesn't matter if the game actually came out after the comic. The game was in development for quite some time before the comic, and the storyline, characters, and powers are worked out well in advance to give the programmers time to make the game. So Capcom certainly knew all of those game story points well before we started work on the comic.

How did featuring The Ferret in issue #3 come about?

TM: I think Scott Rosenberg might've suggested it as a way to boost one of our characters and create a little promotional opportunity, and then it went ahead with Capcom's approval.

Issue #1 mentioned a six-issue story arc, the first three issues available as "Gold Editions", and Blanka art in #3. How early did you see the writing on the wall regarding cancellation?

TM: There was no writing on the wall to see. My understanding is this: Capcom is a huge company. We only dealt with the northern California office and a handful of their licensing and creative staff. When the rest of the executives saw the negative fan reaction to the first issue at the time of publication, they wanted to stop production. All parties agreed to end it after the third issue, allowing us to use up the material created thus far.

The Japanese manga adaptation by Masaomi Kanzaki (Tokuma Publishing) reached the USA in April 1994, just five months after the Malibu comic ended. I'm speculating, but it seems maybe as if yours was cancelled to make way for it?

TM: It's best not to speculate. Malibu's Street Fighter cancellation had nothing to do with any upcoming Japanese adaptation. You're going down the wrong path. The Street Fighter comic was cancelled because Capcom didn't like it. It really is that simple. Your questions are a little dismaying because you seem intent on the idea that Malibu tried to slip something past the licensor and got caught, which is a fundamental misunderstanding of how licensed comics work.

How did Capcom announce to Malibu they wanted to cancel it? Was there an attempt to negotiate or avert this?

TM: That was a discussion Capcom had with Scott. I wasn't involved, but since there was a contract between the two companies, I'm certain a negotiation was involved to try to continue and when that failed, then one to end the arrangement.

Malibu listed Capcom's address in the epilogue at the end... I sensed bitterness over Capcom's decision to cancel.

TM: No bitterness at all. Malibu had a small staff and we couldn't spend the time answering questions – so we just referred everyone to the source. Capcom had resources in place to handle questions about their games.

It was a business deal that went south. It happens sometimes. Malibu published 25 books a month, so you shed a tear and move on. No one holds grudges over something like that, or glares at each other in the hallway at the San Diego Comic-Con. That just doesn't happen. Everyone's a professional.

In issue #1 a letters page was promised, but never materialised. Did readers write in, what was the reaction like?

TM: I don't think we had enough letters to justify a page. That happens too. A lot of our books didn't generate fan mail – that's why letters pages were phased out by other publishers too.

Was it really "Malibu's Hottest Comic", as stated on the cover?

TM: Hahaha! I have no idea. That might just be marketing hype. The Fantastic Four used the cover headline "The World's Greatest Comic Magazine" and The Avengers were headlined as "Earth's Mightiest Super-Heroes". Are those true? It means nothing literal – just something to help create excitement at the point of sale.

Did the cancellation cost Malibu financially?

TM: Only if you count the money that would've come to us had the series continued. There's no penalty beyond that. The three issues we did sold very well and Malibu did well financially.

Leonard Strazewski (Lead Writer, Mailbu Street Fighter Series)

Strazewski began his professional writing career aged 19 and has an accomplished background in journalism. He started with comics in 1987, building a large portfolio at DC Comics, including The Flash. He's a professor of journalism at Columbia College Chicago and a member of its Board of Trustees, and is now retired. Strazewski served as lead writer on the Mailbu Street Fighter series.

It's been [nearly 30] years since the first issue of Malibu's Street Fighter comic went on sale. How do you feel about it?

LS: Oh, it's fun. People ask me about it, people still ask me about it all the time. Particularly, I've had correspondence from people in the Philippines. I don't know exactly why, but I guess the game is extremely popular, still, in the Philippines.

In Tom Mason's introduction in issue #1, he mentioned that when the deal came through he first thought of you. Describe how you first came to work with Malibu.

LS: Malibu had gotten some venture capital funding and was looking to develop what became the Malibu Ultraverse, which was a superhero universe that eventually was sold to Marvel Comics. And Malibu was putting together a team of seven writers who would create this universe. There was myself, Gerard Jones, Mike Barr, James Robinson, [also James Hudnall], Steve Englehart, and Steve Gerber. So we started having conversations, and at the time when they asked me to look at the Street Fighter stuff, we were all deep in the creation of the Ultraverse. So I'm from Chicago, and I was going on to California pretty much one week a month for a year or two – as we worked on those projects. The Street Fighter project was really kind of a side development, while we were working on a much bigger universe.

If I understand the chronology correctly: a Capcom representative travelled to Malibu, met you and Tom, you played Street Fighter II, and chatted over the comic with them?

LS: Yeah, they gave us a lot of background, they actually gave us the game. There was a game that they'd had delivered to the office, so then I played it on the Super Nintendo. Yes, I was very interested, I enjoyed the game. I played it at the arcades, so yeah, we came in and there were a couple of the game developers, we talked a lot about the game.

You know, the Capcom folks were mainly interested in the moves, and the "game moves". They showed me a videotape of the game's special moves, and various characters interacting, and while I was very interested in that, because conflict was an important part of doing the comic, I was less interested in the moves than I was in trying to develop a real story, a real narrative about the characters. I have to admit, the Capcom guys did a great job in creating character backgrounds. They gave me a lot of background material, the biographies of the characters. This was all very helpful.

Did you say that you actually met with the game's creators?

LS: Well, I met with a couple of guys who I think were developers. I don't know that there was any one person that I remember as being, you know, the "kingpin" of the creators. But I did meet with a couple of game developers.

How many times did you meet with Capcom? Just once, to flesh out ideas and receive materials, or multiple meetings?

LS: No, just the one meeting that I recall. And again, Tom may have met with them, the Malibu executives may have met with the Capcom executives at other times, but I just had one meeting with the Capcom guys.

Did Capcom give you any stipulations or restrictions – did they say no to any initial ideas?

LS: Not that I recall. Because I was working with some pretty extensive character biographies, I wasn't going to change the nature of the characters. Ken was Ken, Ryu was Ryu, you know, and Chun-Li was Chun-Li. They were all going to be as Capcom developed them. I had some plot moves, some surprises.

I still get grief about killing Ken! Which was never a permanent thing. In comics, death is not necessarily permanent. And I did have a couple of different possibilities for reviving the character. I mean, he appeared dead, but I get Facebook messages from people saying: "Why did you kill Ken?!" Well, you know, it was a plot thing. If we'd been given the full run of the comic, Ken would have been revived and he would have been jumping around throwing fireballs by issue #5.

In the epilogue, issue #3, it said Ken wasn't actually dead, just recovering, and if it had continued he'd have been brought back. Issue #1 mentioned a six-issue story arc had been planned.

LS: Yeah! I think we were going to... You know, I don't have all the details, because I was working in advance, but not quite six issues in advance. But I knew how it was going to come out. I knew we were going to reunite the two key characters, Ken and Ryu, and they were going to take on Bison by issue #6. When I got the notice that it was cancelled, well, I just stopped thinking about it.

How was the cancellation announced?

LS: I heard about it from Tom Mason and Chris Ulm, so they were the ones who were the point of contact on that. I think there may have been another script that was written, and went unpublished, but I don't even recall. I just know that Chris and Tom said, you know, Capcom has some issues, I think we're going to have to cancel it. And at that time I was deeply engaged in the Malibu Ultraverse, and I was like, alright, fine, I've got plenty of work to do.

Was there an attempt to avert the cancellation and negotiate with Capcom? Do you know specifics of what Capcom disliked?

LS: Not specifically. I do know that we did get some letters, and there was some feedback about the Americanising of the dialogue. So for example, Ken and Ryu's fireball move, I changed from the Japanese to just "fireball". Because it was for a US audience. So there may have been some issues about getting at the underlying language, and things that were in many ways memorable about the game.

But I don't know if that was the real issue. I just know that we had heard... I had gotten some letters on that, and Capcom was very focused on maintaining what they had created. So virtually any minor issue, any minor change in the characters, we'd hear from Capcom: "It's not supposed to be that way." And we'd say, "OK".

They pointed out specific things they didn't like being changed?

LS: Yeah, that's what I recall. And those were usually communicated to me by Tom and Chris. They weren't big issues, and probably could have been corrected at the editorial level, but you know... Game developers and comic writers have different goals. Game developers, at least as I understood it then, wanted to create narratives that got people to the game's moves. That got them into the conflict. Comic writers, myself notably, want stories to be fulfilled with the conflict being part of the story, but not necessarily the centrepiece of the story.

Can you recall how featuring Sheng Long came about? He's mentioned in the game's dialogue, but as a character only came about after EGM did its infamous April Fool's joke.

LS: Yeah, he was in the bios that I was given for Ken and Ryu, and the other characters mention that Ken and Ryu had trained together with Sheng Long. I thought that was a good point of commonality, it helped create an understanding of the bond between the characters, and I liked the idea of having sort of different generations within the groups of characters. So that's how he got there – I put him in.

How did Capcom react? We hadn't seen him in the games, and in the comic he's obscured.

LS: You know, I can't recall. I don't think there were any problems necessarily. Remember, that character was in the bios, so they knew that it was fair game for use in the comics, even though he had not been active in the game.

In issue #2, on page 8, there's a photo of a woman on Bison's desk which was never explained. Can you recall that?

LS: I know the scene, but I don't recall what... I have a vague recollection of the background material, we may have talked about it – Bison having a daughter. But my memory is very vague on that. That's the kind of detail that an artist might have added to the depiction, just to try to flesh out the scene.

Something I thought was fun is issue #3, there's dialogue by The Ferret mentioning Mike Haggar from Capcom's Final Fight.

LS: Well, The Ferret was really a recommendation from Chris and Tom, because it was a Malibu character, and we wanted to try to bring the worlds a little closer together. So I think the Haggar reference came from Chris and Tom; that was not something I was really engaged with, but I think they were trying to bring the Malibu worlds and the Capcom worlds closer together.

The issue #3 epilogue references Bison creating evil clones of the warriors. Was this in reference to the fact you could have the same characters fight each other with altered colour palettes?

LS: You know, I think I was aware of that, and I kinda liked that notion... But actually the clones, I don't know if that came from the Capcom background or not, but I wanted to introduce clones because that's how I was bringing Ken back.

He was to be a clone when he came back?

LS: Well, he was going to be the real guy, but the one that we saw die in battle was going to have been a clone.

Interesting! Do you still have your materials?

LS: God no, not even close! <laughs> Since I did that work, I've done about 200 total comic books. And many before the Street Fighter game; I did a lot of work for DC comics. Then Malibu and Marvel. But I'm also a college professor and have been so for 20 years. So most of the notes I have, actually have nothing to do with that. They have to do with kids' grades!

Do you remember Capcom's reaction to the first issue when it came out?

LS: I think we had good feedback. Again, my feedback was filtered through Tom and Chris, but as far as I recall we had good feedback. I think we had some feedback outside of Capcom, that the comic book was more violent than some folks had anticipated.

Did you get reader's letters or reaction from critics?

LS: Yeah, actually we did get a fair amount of letters. Had the series continued, I'm sure we would have done a letters column. With letters columns, you're working on comics three to five months in advance, so the fact that a letters column did not appear... You know, it was just that we didn't have enough time to get those developed and in. But I do recall letters. There was a fair amount of nitpicking. It was things like, "Why is this not in Japanese? Why is he saying fireball?" So there were always some details – the hardcore gamers wanted every aspect of the conflicts to be very much like the game. And sometimes that would not be something which I wanted to do. I wanted a stronger narrative. But generally, people were very excited; this was a very, very popular game, and seeing the characters come alive in a different venue was something that was very popular. I don't recall the reviews. The only thing I really remember much, was that there was a sense that it was too violent.

You mentioned having Ultraverse work to do when the comic was cancelled. I'm trying to get a feel for any repercussions the Street Fighter cancellation had. Was there a feeling at Malibu it hindered business?

LS: I don't think Malibu ever wanted to lose business. Scott Rosenberg was trying to build a company and wanted good relations, wanted relations in the games community. But no, the Ultraverse at that point was really catching on. It launched very well, there was a lot of marketing going on, a lot of appearances at conventions, so I think... Well, I'm sure the Malibu guys were frustrated because they wanted to take this to completion. But I don't think it had any kind of long-term effect on the company.

You mentioned a script for issue #4. Is there a draft of that?

LS: That would be a question for Tom! He's been the archivist of most Malibu things. Certainly, nothing that I have. And the computers that anything would have been written on have long since been recycled.

Anything else you'd like to add?

LS: Yeah, actually! It's sort of... I found the reaction... First of all, I didn't find the comic book very violent. And I guess, because this was a martial arts game comic, violence was part of the conflict built into the game. But about three years ago, my college did an exhibition of my comics work. I'm a journalism professor, I teach investigative reporting, data journalism, and graduate classes – so I don't really teach much in terms of comics. I've done one small comics writing course. But about three years ago, when I was associate provost to the college, my boss the provost, which is the chief academic officer, took a look at my curriculum vitae and realised that I'd done lots and lots of comics, which is something that surprised her. So the college did an exhibition of my work, where we chose five artists, and we did not include the Street Fighter work. We focused on some other things. But when she introduced the exhibition at the opening, one of the first things she said was: "And some of you probably don't know, that Len is a murderer. He killed Ken in the Street Fighter comic!" <laughs>

So here it was 15, close to 20 years after this comic, and the most striking thing that some people recognise in the comics, was the killing of that character in the second issue. So even though, again, it's comics – I knew that character was coming back – apparently that had much more of an impact than I imagined. Anyway, I always found that fascinating.

As mentioned though, the Ken who was killed would be revealed to be a clone?

LS: Yes. <laughs> And that was one of the things with Bison having clones. Somewhere in the series, the clone technology would have surfaced, so we could – as the game did – have characters fighting each other. I wanted to drop that in, by having a clone killed early on. Though no one knew it except me and the editors. So the readers were, I guess, very surprised by that.

Jademan Comics: Time Travel, Aliens And More

The legacy of Jademan Comics has already been covered in-depth online and in print. Jademan was started by Wong Yuk Long (aka: Tony Wong), who began publishing comics in his teens. At its height, Jademan has been estimated to have held as much as 90% of the Hong Kong comics market. Many hundreds of issues and innumerable stories bore the Jademan logo.

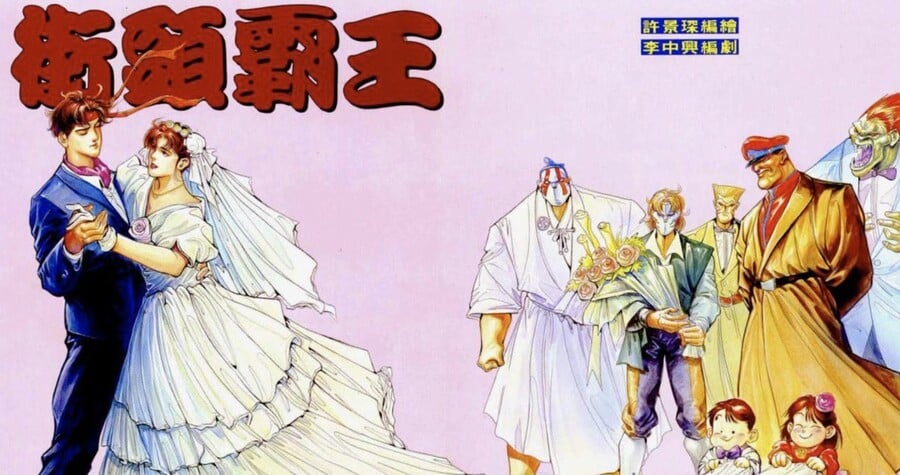

Jademan's Street Fighter series (titled Gaai Tau Baa Wong, lit. "Street Overlords") was officially licensed and, in fact, the first Street Fighter II comic to exist; the beautiful art style is more similar to classical Chinese paintings than it is to Japanese manga. There's some seriously gorgeous artwork in these publications.

According to one source, Jademan's adaptation launched in August 1991 and ran for a total of 113 issues, all written in Traditional Chinese. The official license, however, was only secured from issue 65 (November 1992) onwards. It's also amazingly bizarre, featuring time travel, outer space and alien god monsters, while the cast of characters has backstories and narratives that take massive liberties with the source material.

Chun-Li is Vega / Bison's step-daughter, for example, and at one point demon offspring and giant lizards join the story. There's even some crossover with SNK's Art of Fighting series. It's all over the place in the most endearing way possible.

Despite their weirdness – which is detailed here – the Jademan comics are still well worth seeking out if you can find them, and, as I mentioned previously, they are of such high quality artistically that they were often mistaken by westerners for the Japanese manga adaptation of the video game.

UK Comics: Reheated Manga And Oli Frey Magic

Not long after the Malibu comic stopped, the manga by Masaomi Kanzaki was released in the US and UK as an eight-part series. In the UK, it was handled by Manga Publishing (the print arm of Manga Video, one of the first UK companies to officially release anime in the region – it was behind the UK version of Akira) and was followed by adaptations of the live-action film (two parts), and anime film (six parts). The latter scrapped and redid most of the story.

More interesting is the fact that another, unreleased comic adaptation of Street Fighter was in the works. and it featured the talents of Oli Frey, the legendary artist behind Crash and Zzap! 64 magazine covers.

Former games journalist Nick Roberts explains:

I'm the former Editor-in-Chief of Retro Gamer magazine. On a recent spring clean of my far too large magazine collection I stumbled across a dummy copy of an Impact Magazines Street Fighter II comic. It was around the time we were working on SNES Force and N-Force magazines. The artwork was drawn by Crash and Zzap! 64 cover artist Oliver Frey, and officially sanctioned by Capcom if I recall. I gifted my copy back to Oliver Frey and Roger Kean, as it was missing from their collection. I don't believe it ever got to an official publication, but it's certainly a curiosity of the 1990s. Darn, I should have kept it!

Roger Kean, who worked with Frey at Crash and Zzap! 64 publisher Newsfield as well as Europress Impact Magazines, adds:

During 1992, Europress Impact Magazines Ltd. was contracted by Merlin to create a sticker album and sticker sets of Street Fighter II, licensed from Capcom. A mix of screenshots and original character paintings by Oliver Frey formed the single and multi-part sticker art, which was set into spread backgrounds in the album consisting of large situation-action paintings by Oliver; I created the basic storyline together with input from Merlin people in Milton Keynes.

From this project, the comic was born. Kean continues:

Following on from this, Oliver set out to create a periodical comic of SFII. I wrote an outline and Oliver drew and coloured three sample pages and a cover, which was submitted to Capcom UK as a printed dummy, repeating the pages to bulk.

As part of the masthead we suggested artists other than Oliver, who would not have the time to provide all the art were it given the go ahead. These were Ron Smith, Mike White, John Haward, and Carlos Pino, chosen by Oliver. They did not, however, have any part in the dummy production beyond evincing an interest if the project went ahead. In fact Mike White much later did a large amount of work for our Thalamus Publishing company which produced illustrated reference books for the international market (2000–2010).

Having approved production of the proposal and dummy, Capcom rejected the project. I don't really recall what the reasons were now, but the cover plus the three pages of artwork are all that exists - the originals all now sold.

Neither Oliver nor I were aware of [the American comic by Malibu, the Japanese manga by Tokuma, or the Hong Kong comic by Jademan].

So there you have it; this is by no means the complete history of Street Fighter in comic book form – that would require many, many more words – but hopefully it gives some insight into the wild and wacky world of officially-sanctioned comics from the early '90s.

Comments 7

I love alternate reality comics, they tend to be so much more free than the original source material!

NINJA APPROVED

Awesome deep dive

I had no idea these existed before and wow was the era before major IP's were established absolutely bonkers. How....the ****......did they get away with having Sagat and Balrog LITERALLY DECAPITATE KEN.

The 90's were wild man.

Brilliant article, clearly borne out of a love for its subject. Thanks for the read

I do remember the toys created the lore that Ken's last name is Masters, because of legal concerns.

The idea of killing off Kens with bad hair, like in the above picture, should extend to Street Fighter 5.

This was very interesting, though the first guy got a bit annoying toward the end trying to find an agenda in the questioning. I get that it's tricky filling in a narrative around a game like this, but what they came up with sounds like some of the worst aspects of '90s comics writing. The Japanese animated film is one of the best examples of adapting a video game like that into something that was actually rather good.

@sdelfin Oh my gosh they killed Ken, those ba$ta(r)ds.

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...