If you've been checking the website regularly this week, you'll know that we've been posting some previously unpublished (in English, at least) materials that we had translated while researching various topics related to Nintendo.

Well, here's another one that we had hiding away that we thought might be interesting to share for those hoping to find out more about the Nintendo Satellaview — the obscure Japan-exclusive Nintendo add-on from the 90s that allowed users to download video games and other services to their Super Nintendo via a satellite connection.

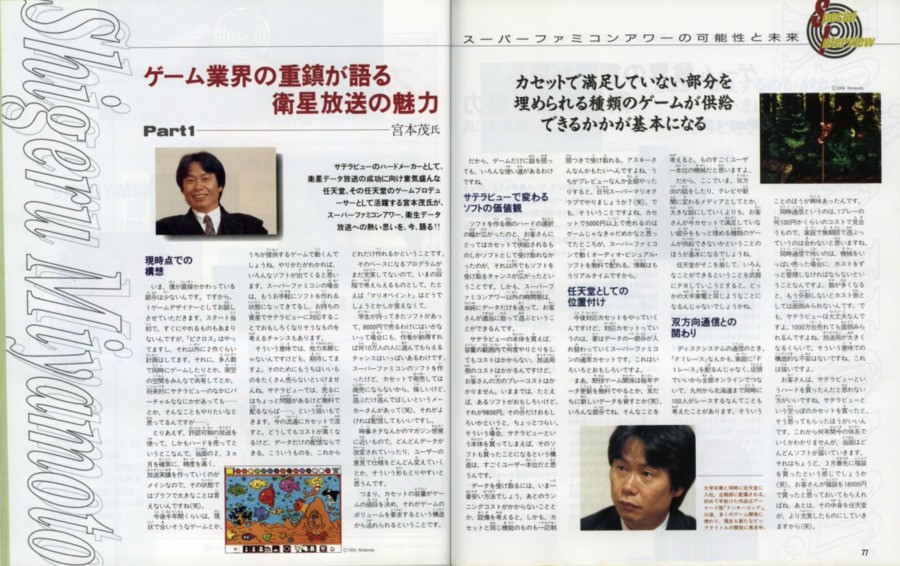

Last year, we put together an article on the Nintendo Satellaview and during our research for the piece, we spoke to the Japanese-to-English translator Stephen Meyerink to help us translate the first part of a series of interviews Satellaview Tsushin did with famous creators about the Satellaview in May 1995, which included a chat with Shigeru Miyamoto about the potential of the device and its Super Famicom Happy Hour. Other people interviewed for this series include Dragon Quest creator Yuji Horii and legendary Square developer Hironobu Sakaguchi, though sadly we haven't been able to translate these.

To begin, Miyamoto asserts in the editorial that he isn't greatly involved with the development of the Satellaview hardware and speaks about the focus on selling hardware and delivering high-quality licensed broadcasting in the early months of the service, while the games are being developed (the service had not yet launched at this point):

"Right now, there aren't a great deal of parts [of Satellaview's hardware development] that I'm involved with, and as such, I'll speak first and foremost as a game designer. Given that it's early days, there aren't a whole lot of things we can do immediately—though we've got Picross, and beyond that about 2 other games planned. Looking farther, perhaps there could be something virtual in Satellaview's future, with games that can be played by many people at once, or sharing an imaginary space together. Those are the sorts of things I'd really like to do.

"For the time being, though, we'll use licensed broadcasting and sell hardware. The main thing will be ensuring that we provide reliable, high-accuracy broadcasting results in the next two or three months. Given that that's our current situation, I can't really bluff or talk about a big game right now (laughs).

He then goes on to talk about how Nintendo will shoulder the burden in the first six months or so of the service's lifespan by using existing assets, but that he hopes that third parties will eventually be able to contribute to the service [Writer's note: various companies did eventually supply games for the Satellaview, including Squaresoft, ASCII, and Chunsoft, among others].

Miyamoto, interestingly, also seems to imply here that the removal of the cost of having to pay to put a game on a cartridge could potentially open up the door for hobbyist developers to release games for the Super Famicom via the Satellaview. This could explain the discovery of some of the more amateur-looking releases that were made available for the service:

"Over the course of the next six months or so, things will probably center around games that suit the current state of the platform, and games that we ourselves at Nintendo make available. I think if we can figure out how to make it happen, there will be a great variety of software released. We're already well-positioned to create new software for the Super Famicom with relative ease, so by leveraging those current assets to support Satellaview, we'll also be able to come up with some fun things for it.

"In that sense, we're not relying on others, but I still have high hopes. That's why we [Nintendo] have to sell lots of good products. Satellaview offers us the the possibility to distribute content for free that might otherwise be difficult to sell. Something like that would incur a high cost if we were to try to sell it on the current cartridge standard, but if we only had to send the data, distribution becomes much more doable. The question really is how much of that kind of content we can produce moving forward.

"The program that will serve as the basis for that isn't yet complete, so in terms of what I can think of at this stage, I could only cite something like Mario Paint as an example.

"Consider also a situation where a student brings in a piece of software, something we can't sell for 8000 yen. If the creator were to consent to distribution, we could theoretically have 100,000 people playing their game. There are many opportunities for that sort of thing to happen with Satellaview. There were also some cases in which developers produced software for the Super Famicom that wouldn't have been profitable to be sold on cartridges, but they wanted people to play the games so badly (laughs). With their permission, we could distribute that kind of content, too."

Following this, he then continues by talking about how customer-friendly the Satellaview setup is, with users only having to pay for the price of the hardware but being allowed to swap the software on the Satellaview's 8mbit cartridges as much as they like without incurring any further costs:

"I think it would make it easier to make changes to the content and adjust the specifications of things based on user feedback, too—much the way a current-affairs magazine could do with its content.

"Essentially, it can allow us to escape the rigid structure of the cartridge size determining a game's price, and thus putting limitations on the volume of a game's data. That's why there are so many ways we can use Satellaview, even just in the sphere of gaming.

"The range of hardware choices has expanded for developing software, and customers who were once limited only to buying that software on cartridges now have more opportunities to get new software outside of that paradigm. What's more, we can simply send along the data alone outside the Super Famicom Hour time slot, and the customer can just grab it and start playing.

"If a customer purchases a Satellaview unit, they can exchange what's on there as many times as they like without any further cost. There is some cost on the side of the broadcasting station, but it doesn't cost the customer anything further to play. As an example—in the past, there might have been a game that looked like fun to someone, but it was priced at 9800 yen. It's a little tough to say if the game looks like 9800 yen worth of fun. In a case like this, if you buy the Satellaview hardware, you've essentially also bought the software up-front. I think that's a very customer-friendly setup."

He then starts to talk about some of the other applications Satellaview might be used for, such as distributing non-gaming software and patches for existing titles. He suggests this is possible because of the low cost of broadcasting data at present.

It's here that he also mentions Nintendo hopes to develop "normal Super Famicom carts" where part of the data can be rewritten. This, we believe, might be an early reference to the Game Processor RAM cassette, which is an incredibly obscure Nintendo-released cartridge from 1996 that was reportedly distributed primarily in schools:

"It's the cheapest way to receive data at present, considering the price of the equipment and the lack of recurring costs. Plus, they can essentially access the same kind of software they could with a cartridge, with only a few restrictions. It'd sure make things tough for you folks at ASCII if we did all our previews with it though, wouldn't it? Why don't we do a daily Super Mario Club? (laughs) But in any event, that's where my thinking is on the subject.

Also, I assumed that we couldn't sell non-gaming software on a cartridge for more than 5000 yen, we COULD distribute audio-visual software that runs on the Super Famicom for free with Satellaview. Information is real-time at this point, after all.

"In the future, we're going to work on producing Satellaview-compatible cartridges. They'd basically be normal Super Famicom carts where part of the data can be rewritten. This would have a lot of interesting applications.

"You could update the player stats in a baseball game every year for no charge, you could lend new data to your friends, and so forth (laughs). [It has applications] in lots of places, you know? And when you think about that sort of thing, it really is an incredibly customer-friendly machine, in my opinion."And that's why for the time being, rather than discussing two-way capabilities or viewing it as a medium to replace television or newspapers or some other grand plan, we'll try to build a foundation where we supply the kinds of games that fill in the gaps where customers aren't fully satisfied with cartridge-based games.

"If Nintendo can attack it from that angle and use the fact that it can do so many things to promote the platform, I think we could end up in a similar position in some respects to other major home electronics."

The final part of the article focuses on Miyamoto's enthusiasm and fears for "simultaneous communication", essentially an early form of networked play.

Miyamoto starts by referencing a 1987 Japanese in-store competition featuring Famicom Grand Prix: F-1 Race that saw users race on a special Famicom Disk Fax version of the game before uploading their scores to Nintendo via a dedicated kiosk fitted with a modem to win prizes. He goes on to suggest that this type of "simultaneous communication" doesn't yet make sense in the context of the home market, as publishers would have to keep the host maintained and keep up with demand, but suggests that Satellaview could be fine in this regard as its broadcasting station will grow along with its user base:

"During the era of Famicom Disk System, I thought, rather than distributing games like Famicom Grand Prix: F1 Race to homes, we could connect everything online via storefronts and let 100 people from Kyushu to Hokkaido race at the same time. I was really interested in that sort of thing.

"Simultaneous communication like that runs about 100 yen per play, so I don't really think that would have been suited to playing indefinitely at home."

"What's frightening about simultaneous communication like that is that if you sell many units of the hardware, you have to keep the host maintained. And as the number of machines connecting increases, the host can't handle the load unless things get divided up. But Satellaview would be fine in that regard. Even if we somehow managed to sell 10 million units, we'd still be able to handle it. The broadcasting station would grow along with the user base, so in that sense, we don't have any structural concerns. And that's a powerful notion.

"It's my hope that when customers buy a Satellaview, they don't think of it as hardware—but rather, an empty cartridge. I can't say at this point how many years the hardware will continue in its current form, but for the time being, it will continue to receive more and more software. It's a little like buying a lucky grab bag in early March (laughs). If customers can think of it as having bought a lucky grab bag for 18,000 yen, Nintendo will continue to make the contents of that bag more and more satisfying for them (laughs)."

If you want to know more about the Satellaview service, we recommend taking a look at our feature from last year, which attempts to document its history in full.