There's really never been a better time to be a retro gamer. Thanks to digital stores, micro consoles and DIY emulation boxes, we now have access to decades of gaming content – most of which can be played on our modern-day HD televisions without having to invest in expensive custom AV cables or dust off original hardware. The appetite for vintage gaming has arguably played a huge part in this deluge of content, which means that, should you feel the urge to sample the classics of yesteryear, then it's not hyperbole to say you're practically spoilt for choice.

Of course, not all of these options are created equal. The NES Classic, for example, is the perfect entry point for casual players – it offers excellent emulation and comes with an authentic controller; another big plus is that it's created by Nintendo itself so is legally watertight and buying it allows you to reward the copyright owner of the original games (before reading on, yes this piece will indeed be talking about the shady practice of using ROMs, so if that kind of discussion brings you out in hives, we'd advise you navigate away from this page immediately). However, critics will point out that, although the emulation is superb, it's still software-based and therefore cannot be considered totally accurate – you're also limited by the fact that the NES Classic cannot be (officially) updated with new games.

That leads us to the other end of the retro gaming spectrum – the hardcore hobbyists who crave accuracy, freedom and customisation over officially-sanctioned product. The history of retro gaming emulation stretches back decades, and modern-day emulation boxes based on the Raspberry Pi are all the rage. These allow you to load up hundreds of ROMs (assuming you're at peace with that kind of behaviour), connect any USB controller you like and much more besides, but even these multi-faceted devices have one glaring flaw in the eyes of purists – they're still based on software emulation. To most people, this is perfectly fine and they probably won't be able to tell the difference from the real thing, but purists crave perfection – and while some would argue that is only possible by using the original hardware, there is an alternative.

Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) chips are essentially chips which can be programmed to behave exactly like original hardware – so we're talking hardware emulation rather than software emulation. Software emulation is, as the name suggests, a piece of software (an emulator) which replicates the performance of an old piece of gaming hardware, and this software then runs on top of the chipset of whatever device it's loaded onto (be that a PC, smartphone or games console, like the Switch with its many arcade and retro titles). With hardware emulation, there is no software layer, and the chip itself is configured to run 'cores' which behave just like the original hardware. The jury is still out in retro gaming circles as to whether or not this can be truly classed as 100% perfect (and FPGA cores are, like emulators, an almost constant work in progress), but cycle-accurate emulation is the objective of many FPGA core developers, and this makes it the option of choice for really dedicated retro fans.

We've already seen FPGA chips inside Analogue's amazing Nt Mini, Super Nt and Mega Sg consoles, as well as RetroUSB's AVS, but the MiSTer FPGA project is a much more ambitious undertaking. It's based on MiST, an effort to replicate the Amiga and ST in a single device (the 'er' comes from "MiST on Terasic board", apparently) and is best summed up as the FPGA equivalent to a Raspberry Pi emulation box; it offers the same level of customisation options and is totally reliant on you loading up ROMs, but it boasts hardware-level accuracy via a range of cores which cover a massive number of consoles, computers, arcade machines and handhelds.

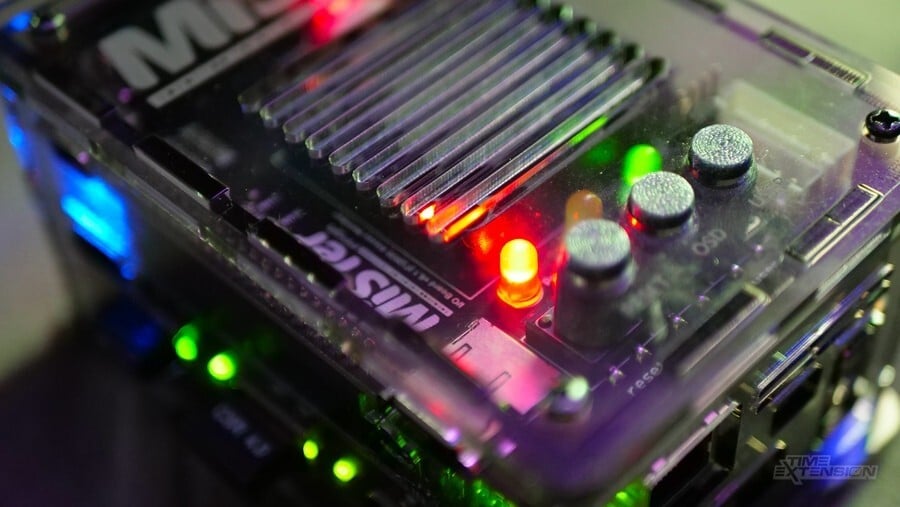

Unlike Analogue's consoles, the MiSTer FPGA is very much a do-it-yourself proposition. The core components consist of the DE10-Nano board, which contains the FPGA chip and RAM. The modular nature of the system means you can create the setup that suits your own needs, but you'll almost certainly need to add an I/O board, fan and powered USB hub so you can connect things like input devices and a WiFi dongle. Many stores sell 'complete' MiSTer units which combine all of these boards into a single device, complete with a protective case.

An extra 128MB RAM module is also highly recommended so you can run some of the more demanding cores. You'll also want a USB keyboard (which is needed for high-level stuff but doesn't have to be connected all of the time) and a USB mouse (which comes in useful if you want to emulate systems like the Amiga and ST). Finally, a power supply to run the whole thing is naturally a must (a 'split plug' option is available, so one plug supplies power to the DN10 while the other powers the aforementioned USB hub), as well as a MicroSD card to house all of your data. All-in, our setup cost well over £300 in 2021, including elements like a case, keyboard and so on – and since then, the price has risen sharply. That may well make MiSTer too rich for some, and a decent Raspberry Pi setup can arguably scratch the same kind of itch for significantly less (it's worth noting that a cheaper MiSTer clone is on the way, and could shake up this sector of the market massively in 2024).

Here's a fairly solid (but by no means comprehensive) list of MiSTer stockists:

- MiSTer Addons (USA)

- Ultimate MiSTer (EU)

- Antonio Villena (Spain)

- Manuferhi (Spain)

- MiSTer FPGA UK (UK, Parts only)

Depending on where you purchase your MiSTer, you may find that the seller has kindly populated your SD card so that all of the current emulator cores are in place, but if you're not that lucky, then the initial setup can be slightly daunting – especially if you've never dabbled in emulation before. Files and folders have to be in the correct place for everything to function and cores have to be updated to ensure you're on the latest version, but thankfully, you can use 'scripts' to streamline this process massively.

These are executed via the MiSTer's basic but easy-to-understand front-end, and take a lot of the heavy-lifting out of getting it configured – such as updating the cores to the latest versions, organising your folders and downloading BIOS files. Theypsilon's "update all" script is the one we used, and it really did make a painful process much easier to stomach. To use this update script – and perform any kind of online activity – you'll naturally need to be connected to the web, either via a wired ethernet connection or using a WiFi dongle (these cost less than £10). It's highly recommended that you download an FTP client for your computer when it comes to manually transferring files to the MiSTer – it will save wear-and-tear on the machine's MicroSD card slot, at least.

Creating an FPGA core for an old retro gaming system is a truly involved process, but there's an active community which has grown up around FPGA technology and the MiSTer benefits directly from that. Since the project began back in 2017, a wide range of platforms has been successfully supported, including pretty much any console and computer prior to the 32-bit era.

As of 2024, that includes NES, Master System, Mega Drive, SNES, Mega CD, Neo Geo, Game Boy Advance, Amiga, ZX Spectrum, N64, Saturn, PlayStation, Amiga and many, many more. Support is also included for arcade games, although many of these have to be treated as individual cores because, outside of a few examples (like Capcom's CPS standard), many arcade games are totally unique in terms of their hardware. At the time of writing, though, an impressive selection of games is available, including the likes of Donkey Kong, Radar Scope, Bubble Bobble and Double Dragon.

CPS1 and CPS2 support has been achieved, while Cave's legendary bullet-hell shmup DoDonPachi is also fully playable on MiSTer, as are Raizing classics such as Battle Garegga and Armed Police Batrider. Sega's arcade heritage is also very well represented here, with classics such as OutRun, Golden Axe, Alien Storm and Shadow Dancer all playable. The sheer number of coin-ops now supported by the platform is staggering and illustrates why this is perhaps the most exciting application for MiSTer because many arcade games remain out of official distribution, and emulation is the only way to experience them.

In terms of performance, the MiSTer really does leave other devices of this type in the dust. The accuracy is astonishing, and once we'd gotten everything configured properly, we didn't encounter a single game that refused to run (something that couldn't be said with software-based platforms we've tried, like the Polymega and Raspberry Pi). What's even more striking is the almost complete absence of input latency; in most cases, we're talking less than 1ms of input lag, which makes it almost indistinguishable from playing on original hardware. When it comes to controllers, pretty much any USB joypad or stick will work (we've been using the controller that comes with the Mega Drive Mini as well as the excellent Astro City Mini arcade stick). You can also use 2.4G pads with the appropriate dongle, while a Bluetooth dongle will allow you to connect controllers wirelessly – oh, and MiSTer now supports the Sinden Light Gun, beating Polymega to the punch.

Add to this the fact that you can tinker with your experience with filter effects – such as integer-scaled, pixel-perfect scanlines – and even order extra components which allow you to plug in your vintage controllers and connect the MiSTer to an old-school CRT television or PVM, and it's easy to see why MiSTer has become so beloved amongst passionate retro aficionados. It's arguably the most accurate way of playing classic games – beyond owning the original hardware and software, of course.

However, MiSTer isn't going to be for everyone. As we touched upon, the initial setup is rather demanding, and even when you've got it working perfectly, the experience isn't as user-friendly as it is on, say, the SNES Classic Edition or the Mega Drive Mini – or the aforementioned Polymega, which is perhaps a closer point of comparison. And, because you've got to load up ROMs and make sure all of the cores are up-to-date, there's a degree of maintenance which goes beyond what console owners are accustomed to, even when using the "update all" script (which throws up a bunch of DOS-style text on the screen that gave us flashbacks of the early '90s and spending days trying to get a sound card to work on our 486 PC). This is not a device which casual gamers are going to feel totally comfortable using, but the more effort you put in, the more you'll get out of it.

The other catch with current FPGA technology is that it has a very defined ceiling at present. It was once assumed that PlayStation, Saturn and N64 simply wouldn't be possible on this device, and while those have all happened now (and proven many doubters wrong), the current generation of FPGA chips is bound to have a limit; we're unlikely to see Dreamcast being replicated on MiSTer, for example. The talented developers behind these amazing FPGA cores may well surprise us, but there's no getting around the fact that, while software emulation can take strides in-line with the chipsets which power the latest PCs and games consoles, replication via FPGA is a lot more limited because developers are having to fit more and more complex systems onto the FPGA chip itself. As more advanced FPGA chips arrive in the future, this will change – as is evidenced by the fact that MiSTer already has potential rivals looming on the horizon.

So, is the MiSTer the best retro gaming system money can buy right now? That's a tricky question to answer, precisely because of all those options we mentioned in the opening paragraph. MiSTer certainly scores points over devices like the Raspberry Pi, largely because the quality of the emulation is so much higher – but machines like the Dreamcast might never become a reality with the current generation of FPGA chips.

You might assume that the MiSTer also blows away the Polymega, a platform which it has consistently been compared to by the retro gaming masses for the past few years. Priced at $450 (a price which doesn't include the additional 'Element Modules' required to load up the various systems it emulates), Polymega is based on software emulation and, therefore, has all of the negatives that involves; it's not completely faithful to the original hardware (for example, its Mega Drive emulator is based on Kega Fusion, which is known to have timing differences when compared to the real deal) and there are many incompatibilities with various games, but – and this is a big one – Polymega is not reliant on ROMs as you can load up your original discs and carts thanks to its modular configuration.

It also supports original controllers (via the aforementioned Element Modules) and is a lot easier to get up and running than MiSTer; in fact, it's as easy as turning on a Nintendo Switch or PlayStation 5. As is the case with the NES and SNES Classic Editions, the emulation on the Polymega will be more than good enough for the vast majority of players.

It's also worth noting that, although MiSTer is more accurate than the Raspberry Pi, it's also a lot more expensive, and, given that the Raspberry Pi boasts a more diverse range of supported systems at present, those who aren't sticklers for 100% faithfulness might see the price difference between the two as off-putting.

Which really brings us back to that opening paragraph; retro gamers have never had it better than they do today when it comes to options. Which of these options is best? It really depends on what you want. If you're just looking to brush up on the best SNES games, then you're probably better off picking up a SNES Classic and leaving it at that. Got a massive library of classic games and discs, and don't want to spend days tinkering with configuration files and ROMs? The Polymega might be more up your street. Have an urge to dabble in emulation and ROMs but don't want to break the bank? A cheap Raspberry Pi will probably meet your needs.

However, for those who don't mind getting their hands dirty and crave the degree of accuracy that software emulation rarely provides, the MiSTer FPGA is a truly mouth-watering prospect – and one which is only going to get better over time. Indeed, it's easy to argue that machines like this – based on super-accurate hardware-based emulation rather than software-based emulation – are the true future of retro gaming.