Don't worry – you're not suffering from déjà vu. If you feel like you've read this before, it's because we're republishing some of our favourite features from the past year as part of our Best of 2024 celebrations. If this is new to you, then enjoy reading it for the first time! This piece was originally published on January 24th, 2024.

In our Lost Zelda Games article, we mentioned interviewing the gentleman behind the Nintendo Adventure Books. Reaching that point required an interesting detour - the books were credited to Clyde Bosco, Bill McCay, and Matt Wayne, all of whom seemed impossible to find online (the comic artist Matt Wayne is not the same person). However, we were able to find Russell Ginns, whose website mentions the books briefly. Unsure of what to expect, we made contact, hoping maybe he knew one of the authors or could point us in their direction. As it turns out, all the books were written under pseudonyms.

His reply was jovial. "I'm Russell Ginns, aka Clyde Bosco, aka R U Ginns, aka Matt Wayne. I'm glad you're having fun diving into ancient texts and primordial game design. And I'm happy to answer any questions I can. This is a great blast from the past. Give me a day or so to try to recall some more of the details or anecdotes for you. It was more than a few years ago! <laughs>"

This was quite the revelation. Looking over his CV revealed numerous other projects Ginns was involved with. Along with his Nintendo work, other clients included Sega, Electronic Arts, The Learning Company, and Valve - he was involved in Half-Life, earning a thank-you credit. He also created Castle Infinity in 1996, one of the first massively multiplayer online games. MobyGames credits him as the designer on Lode Runner 3-D for the N64. He was also involved in casual games, board games, puzzles, live-action and animated videos, Sesame Street, plus a multitude of children's books.

Looking over this dizzying array of media, it doesn't feel far-fetched to describe Russell Ginns as a multi-talented modern-day bard. The Nintendo Adventure Books were merely one aspect of his oeuvre.

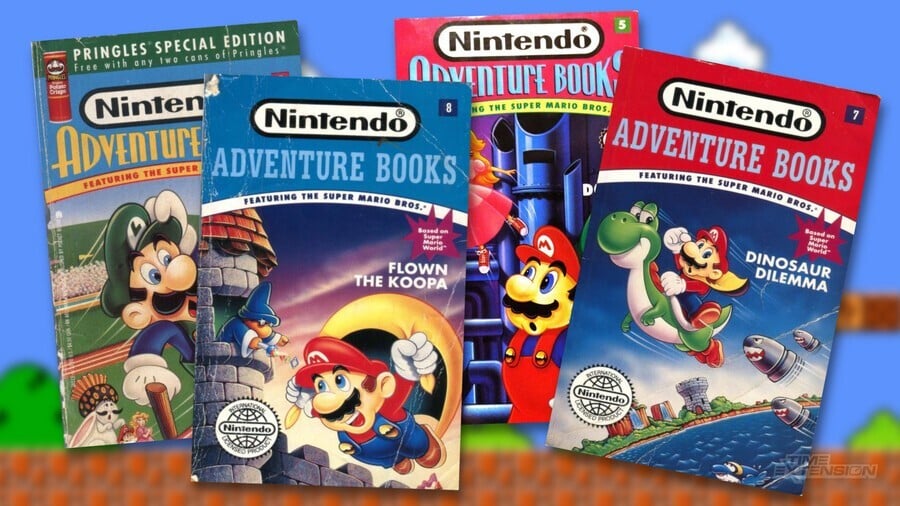

The full list of Nintendo Adventure Books is follows:

- Double Trouble - Clyde Bosco

- Leaping Lizards - Clyde Bosco

- Monster Mix-Up - Bill McCay

- Koopa Capers - Bill McCay

- Pipe Down! - Clyde Bosco

- Doors to Doom - Bill McCay

- Dinosaur Dilemma - Clyde Bosco

- Flown the Koopa - Matt Wayne

- The Crystal Trap - Matt Wayne

- The Shadow Prince - Matt Wayne

- Unjust Desserts - Matt Wayne

- Brain Drain - Matt Wayne

First though, did he write all of them?

"I am confident I wrote books 1, 2, 5, 7 and 8," recalls Ginns, adding that "I might have written 10. And I'm pretty sure I did 6, but I could be mistaken. I'm trying to recall who wrote the other books. I developed the whole series concept, but now that I think about the Zelda titles, I think a guy named Ritchie Chevat was the author of those two. I worked with him way back. Lovely fun guy. I might have his info for you somewhere."

We contacted Mr Chevat, though he admitted that after so much time, it was difficult to remember exactly which he'd worked on, and politely declined to be interviewed. The copyright page on #9 does list Richard Chevat, while #10 lists Roger Peckinpaugh. No problem, though, since Ginns' portfolio provided ample discussion.

We asked Ginns how he got involved with Nintendo, and to describe the start of the project. As he explained, "I was working as a puzzle creator and game reviewer for 3-2-1 Contact, a science magazine based on the Sesame Workshop TV show, when I was approached by editors at Simon & Schuster to create a book series based on Nintendo products in time for the US launch of Super Mario Bros. 4 [this is Super Mario World; the Japanese box retains the 'Super Mario Bros. 4' subtitle]."

Here, it's important to lay out the chronology of releases, since there are a few discrepancies online. The first book came out in June 1991; this is the date on its copyright page. The US release of the SNES hardware along with Super Mario World was around two months later, in August, so the books would have provided a nice build-up. The second book is also attributed to June. Afterwards, they came out roughly every month; UK editions came over about a year later. The US edition of book #6 states October 1991. Book #7, Dinosaur Dilemma, is the first with an overt SNES connection since it has Yoshi on the cover; Amazon US cites this as November 1991.

With work starting before June, we were curious about what sort of materials Nintendo provided in order to facilitate the tie-in. The SNES wouldn't arrive for some months. "The game and system wasn't available in the US yet," agrees Ginns, explaining, "So they shipped me a Super Famicom and a copy of Mario, and then later a copy of Zelda, as well."

Ginns really emphasises the words Super Famicom, so there can be no mistake. One of the perks of the job was getting access to Nintendo's 16-bit hardware before most average US consumers did. His mentioning of Zelda raises another important point on chronology. The Japanese SFC release, Kamigami no Triforce, came out in November 1991. The US release, A Link to the Past, came out in April 1992. However, the two Zelda books, The Crystal Trap and The Shadow Prince, came out between these two dates, in January and February 1992, respectively. Ginns maybe didn't pen these himself, but he was supplied with research material ahead of time (we're only a little bit jealous).

Accepting the events as stated shows a fairly conventional scenario of a product or toy maker, Nintendo, branching out into adjacent products and media. However, when you examine Ginns' recollections alongside several other events from the time - and granted, this is pure speculation on our part - a more interesting picture forms. But let's recount some history first.

We've already covered how Sega failed to capitalise on its 8-bit hardware in Japan. Also, that Nintendo's Famicom initially faced an uphill struggle. Once established, though, the Famicom in Japan and NES in America had complete dominance of the home console market. Meanwhile, in Europe, Sega did better, to the point where Nintendo didn't even officially have a UK office. NEC launched its PC Engine in Japan in late 1987, though its launch line-up was lacklustre, while the TurboGrafx-16 hit America mid-1989. Sega's Mega Drive hit Japan in late 1988, while the Genesis reached America in mid-1989 (thus squaring it off against the TG-16).

What you had then was a three-way fight between competing hardware manufacturers in multiple territories. It took a while for these competitors to find traction, but in Japan slowly NEC gained popularity; in David Sheff's book Game Over, he states Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi viewed NEC as a threat due to its heavy investment in R&D and its inexpensive access to microchips. Meanwhile, in America, Sega eventually did extremely well, with Tom Kalinske giving some great anecdotes. Nintendo wouldn't launch its 16-bit successor until November 1990 in Japan, August 1991 in America, and April 1992 in the UK. The Super Famicom had been in development for years already, but Nintendo had been in no hurry.

We've simplified and glanced over events, but to us, this paints a global picture of Nintendo gradually losing market share and then scrambling to maintain relevance. Sheff explicitly states Nintendo had become "fat and happy [...] a sense of invulnerability". This led to a period where the company started pushing out on various fronts to boost publicity and brand awareness. For example, in late 1989, there were the Mario and Zelda cartoons in America - the creation of which is fascinating. Surprisingly, Nintendo "had very little oversight", according to those involved.

In 1990, Nintendo partnered with Valiant Comics to produce the Nintendo Comics System series. Then, in late 1991 there was the Super Mario World TV series, starting about a month after the US release of the SNES. As another example, in the UK in 1993, there was the Golden Ticket competition. Our interviewee Frank O'Connor stated: "The competition came about as a result of Nintendo UK trying to boost their visibility. A push to do something splashy, customer-focused, and unique." There were also Nintendo-themed films: the Fred Savage road movie, The Wizard in 1989, and the original Super Mario Bros. film from 1993.

Nestled somewhere between all these disparate events, starting in June 1991, was the 12-volume Nintendo Adventure Book series. Again, we've glanced over things, but when you look at Nintendo as a whole, these books fit nicely into what appears to be a long-term global marketing strategy. Kids would watch the cartoons, watch the films, buy the comics, then read the books and possibly even see them in their school libraries. It was a multi-pronged publicity bonanza that had Nintendo and its mascots visible everywhere. So supplying Ginns with a Japanese Super Famicom and copies of games before they hit America was an ingenious move, allowing him to produce content that synchronised with the domestic launches.

Taking on Nintendo's core properties, though, must have been daunting. What sort of guidance was provided?

"I met several times with comics legend Jim Shooter, of Valiant Comics," explains Ginns, "He was launching a Nintendo comics line at the time. So, I basically had the games and a few comics as references for the series. There could very well be characters in the books that came from the comics that aren't present in the games much, if at all. Is Wooster in any of the games?"

Prompted by Ginns' question, we actually looked this up, and as it turns out, Wooster was exclusive to the comics and books – but it's a nice example of the cross-pollination that occurred across mediums. It also brings up questions about Nintendo's involvement; as stated earlier, the production crew on the Zelda cartoon had little interference from Nintendo. So we asked Ginns if there was any input from above.

"Other than the games and comics, I really didn't get any input from the licensors," admits Ginns. "Which is pretty amazing compared to how things are run now. The only specific feedback I got was that I must always use 'Bros.' instead of 'Brothers'. Also, somebody somewhere suggested that Mario and Link use 'modern' language like, 'that's fresh', but I categorically refused."

It's actually something we've heard a few times; the late Dale DeSharone, who produced the Philips CDi Zelda games, also didn't get much feedback from Nintendo. Even so, it continues to be surprising when contrasted against modern Nintendo, which is fiercely protective of its IP. Did Ginns have to run anything by them?

"I submitted a few sentences for the first two books to get approval," he explains before providing an example. For one of the books, it was:

'Hi Bowser,' said Mario.

'Hi, Lunch,' said Bowser.

"That was it."

Presumably, then Ginns would have been free to create pretty much any sort of story he wished? Not quite.

"Soon, I was told they were finalising the covers ahead of time," he reveals. "So I based the stories on the cover images and book titles. It's kinda the way B-movies got made in the 1950s; the 'Curse of the Cat People' posters were printed first. Then they wrote and shot the film."

We've actually heard about this happening in Hollywood quite often, too, even up to the days of Cannon Films in the 1980s. The documentary Electric Boogaloo has a great story about Cannon shopping around posters even before filming had begun. Sometimes the promised actor shown on the poster changed by the time of filming! The fact something similar happened with these books is a little surprising. The man credited with painting the covers, according to the copyright pages, was Greg Wray.

As for the books themselves, they're a lot of fun. They're aimed at children, obviously, but we can easily imagine that if one were a kid immersed in Nintendo games, it would possibly be the best thing ever. Think back to the days when teachers expected everyone in the class to have a book of some sort, for mandatory reading periods, and then, in these periods, being able to "play" your favourite games. It's not quite sneaking a Game Boy into class, but you could play openly without anyone being the wiser.

All of the books integrate themselves with the still nascent game lore amusingly, too. The first book, for example, has an amusing description of how initially the plumbers had to listen for Princess Toadstool's voice ringing through the pipes, but since then they'd upgraded their system to include computers, telescopes, homing pigeons, and TV monitors. It's worth noting that the first Super Mario Bros. game came out 1985 (we're ignoring the earlier Mario Bros. game), so the setting in 1991 was still fresh. Today, it's well entrenched, but at the time, even Nintendo hadn't fully established things canonically. Super Mario Bros. 2 in America, as is well known, was a reskin of Doki Doki Panic. So there was still flexibility.

Of course, these weren't straight narrative stories - they were adventure books where readers decided what the protagonists did. As well as choosing actions and flipping to the corresponding page describing the outcome, there were puzzles to solve, which gave clues as to the correct choices. It was also possible to choose poorly and reach a sticky ending.

Having tried all manner of such books, from the original Choose Your Own Adventure series, through to the Fighting Fantasy series, and now these, we've always been curious about the methods of creation. How does an author keep track of so many branching threads?

"For each story, I started by making a big flow chart on graph paper with the whole story in four to five-word boxes," says Ginns, before elaborating on the various bad endings. "I made it a personal challenge to give every dead end a completely different 'game over' death, so things got rather surreal. They get pitted, flattened, and turned into sandwiches. I had hopes that someday I'd publish a book called 'Game Over' that included just the pages where Mario, Luigi, and Link meet violent dooms a few hundred times."

Sadly, this amusing compilation never came to pass, and the title ended up being used by David Sheff for his own book. Still, Ginns wrote several books in a very short period of time, when you look at the publishing dates. By our very, very rough calculations, it must have been over 100 pages a month! Were the deadlines stressful? How did it all finish?

"I wound up writing [maybe over half] of the 12 books in the series before my head started to explode. Then they got other writers on board," he admits. "Soon after, a friend pointed out that I was creating 'slow software', so I moved to Seattle and got involved in designing video games."

Finally, we ask Ginns if he has any amusing anecdotes related to the books. He doesn't disappoint. "There's a potential Random House promotion in the works for my silly horror stories series, 1-2-3 Scream!, that gives you a free copy when you buy a can of Pringles. That was one of the promotions for the Nintendo Adventure Books as well. I believe this will make me the only author in history to have two different book series come free if you purchase a cylinder of dehydrated processed potato."

If anyone is curious to read the Nintendo Adventure Books, they're available on eBay, but we were able to find the entire series on the Internet Archive, too.