Don't worry – you're not suffering from déjà vu. If you feel like you've read this before, it's because we're republishing some of our favourite features from the past year as part of our Best of 2024 celebrations. If this is new to you, then enjoy reading it for the first time! This piece was originally published on November 11th, 2024.

Few games can claim to be as influential as Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord.

Originally released in 1981 for the Apple II computers, it was one of the first Dungeon & Dragons-style role-playing games available for home computers and has since gone on to inspire countless developers, including, most notably, the creators of popular RPG games like Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy.

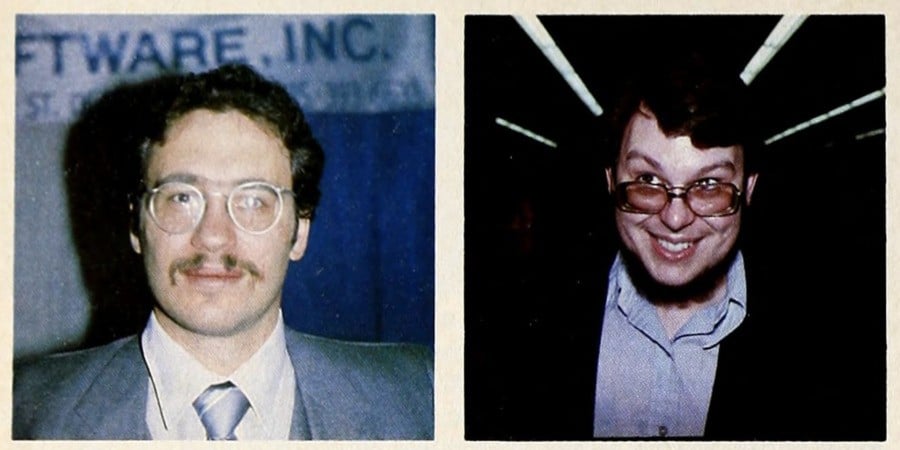

Created by the programming partnership of Andrew C. Greenberg and Robert Woodhead, Wizardry tasked players with descending into a labyrinth situated beneath the castle of the mad overlord Trebor, in search of a stolen treasure. There players would face off against all manner of monsters, including giants, orcs, vampires, and slimes, earning experience points from battles and collecting new items to help them prepare for the final fight against an evil wizard named Werdna.

Over the years, there have been various sequels and spin-offs to Wizardry as well as remakes and ports to other platforms, but today, we wanted to focus our attention on the granddaddy of them all: the original Apple II Wizardry. So we got in touch with some of the key people involved in the making of the game, to learn a little more about the circumstances around its creation and the people who brought it to life — starting with its co-creator Robert Woodhead.

Discovering PLATO & An Involuntary "Sabbatical"

Robert Woodhead was born in 1959, in the Tunbridge Wells area of Kent, England, but moved to Canada at the age of 7, and then to the US when he was in his early teens. Growing up in the small city of Ogdensburg in upstate New York, he showed a great deal of interest in a lot of different hobbies as a kid, including being an avid reader of science fiction novels and experimenting with amateur radio. However, it was his preoccupation with computers that would end up becoming his main obsession

Woodhead first showed an interest in computers while attending high school at the Ogdensburg Free Academy but was unable to study programming classes at the time, as computer science lessons had yet to be added to the school's curriculum. As a result, he sought permission from a local college to use their computer terminal on weekends to learn how to program, enlisting his mum to help him make the 20-mile journey there and back on a weekly basis.

Woodhead recalls, "When I was in high school, I was given permission to use a computer (a PDP-8) and terminal at a local college (St. Lawrence University, if memory serves). My mother drove me there on Saturdays (so two round trips a day [for her]!) and I spent the whole day there. My first textbook was probably 101 BASIC Computer Games though I probably borrowed anything computer-related from the library."

For Woodhead, these trips ended up being a vital first step on the road to becoming a computer programmer, teaching him how to code and execute his own programs. However, it did little to change the fact that there were still very few opportunities in education for young people at the time. So, when he enrolled as a student at Cornell University in 1975, he chose to major in his second favourite subject — psychology — in the absence of a computer science undergraduate, as it presented him with the best opportunity to spend some quality time with the university's PLATO computer system.

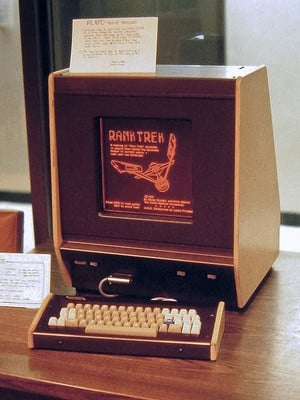

PLATO, in case you've never heard of it, was an educational computer network that was originally launched in the early 1960s, and saw multiple users taking advantage of terminals connected to a single mainframe computer, to submit assignments and communicate with their fellow classmates. As Woodhead already knew, though, that wasn't all it could do, with the system also containing a bunch of early computer games — many of which would prove to be important influences on his future work.

"There were dungeon games on PLATO in the same vein as Wizardry," Woodhead tells Time Extension. "But the one thing that PLATO could do that nobody else could do was multiplayer. It had real-time multiplayer graphic games in the mid to late 70s! There was one game, in particular, that I became particularly addicted to called Empire, which was a 30-player real-time space war game where sometimes the games would take days to conclude."

In a retrospective account, Woodhead later described PLATO as "crack for computer nerds". But it wouldn't be the only computer-based addiction that he would pick up during his time at Cornell, as soon he also came into possession of his very first home computer, a TRS-80, and began writing his own games.

"Before I got the TRS-80, I was hired to write inventories and business software for the local computer store," says Woodhead. "I had actually wanted an Apple II, but my boss was selling so many of them he wouldn't give me any sort of in-store discount. And then when I was home during one of the summers, the local Radio Shack had a TRS-80 and they didn't know what to do with it. So they basically sold it to me at cost, just so they wouldn't have to worry about it. When I got back to Cornell that fall, I told my boss, 'Don't worry about the Apple II. I got myself a TRS-80.' And he basically fired me. He likened it to a Ford salesman driving into work in a Chevy."

As you can imagine, with all of these distractions piling up, Woodhead's college work soon began to suffer, as he started skipping classes and shirking assignments to focus on his ever-growing obsession with computers. And, at the end of the fall semester of 1979, the university took notice of this and decided to suspend him for a year, causing his mum to give him something constructive to do during this involuntary "sabbatical", to keep him out of trouble. This is an event that would end up leading — in a roundabout way — to the creation of Wizardry's publisher Sir-Tech.

How Sir-Tech Was Born

To give some context, shortly after Woodhead's family left England, his parents James and Janice had left their jobs as a research chemist and a nurse to set up a business called Resin Sands to manufacture resinated sand for industrial purposes. However, in 1975, James had died from a heart attack, shortly before Woodhead had gone to college, leaving his wife to run the business on her own.

"She was a very quick learner, but she needed somebody who had experienced business sense to help her," says Woodhead. "And that's where Fred Sirotek came in. Fred had invested in a lot of companies and ran a bunch of small companies himself. So when I got thrown out for a year, my mother wanted to give me something to do, so she asked Fred to let me write some software to automate the inventory management for one of his companies."

One of the benefits of this arrangement for Woodhead was that he would finally be able to get his hands on an Apple II computer — a machine that he had always wanted to take a closer look at. So he enthusiastically accepted the position and got to work on creating software for Sirotek, devising a program to calculate the changing costs of raw materials and a mail-order application system.

Both of these proved to be incredibly helpful, and soon Woodhead and Sirotek began discussing the possibility of marketing them to other businesses, leading the programmer to suggest exhibiting the mail order system (under the name Info Tree) at a computer trade show in Trenton, New Jersey. The only issue was how to get there. Reluctant to let Woodhead check the computer in airline baggage, Fred ended up recruiting his son Norman to drive Woodhead to the event.

As Norman Sirotek tells us, "Sir-Tech was born out of a car trip back from Trenton, New Jersey. Robert Woodhead and I were doing one of these college campus trade fairs and we were displaying a product called Info Tree. We did the display, it got a lot of attention at the fair, and our booth was actually the only one that had multiple tiers of people stacked up behind it. And on the drive back, we were discussing what kind of products he was thinking of making."

According to Norman, the show convinced him that there may be a future in computer software, so the pair got together with Norman's father and started a company called Sirotech (which later changed Sir-Tech) in 1979. The idea was to keep making productivity software, but soon Woodhead grew tired of working exclusively on these kinds of programs and began to express an interest in making a game instead — an idea that would eventually evolve into the space game Galactic Attack for the Apple II.

Galactic Attack was a single-player take on Empire — one of the games that Woodhead had previously played at university. It saw players take control of a space shuttle called the USS Blaise Pascal as they flew around the galaxy, eliminating a group of aliens called the Kzinti (named after a race from Larry Niven's Known Space series). To do this, players could attack enemy ships using phasers and torpedoes, alter their warp speed and strafe to evade incoming projectiles, as well as send troops down to a planet to liberate them from the opposing army.

Woodhead completed development work on Galactic Attack between 1979 and 1980, but there was a problem that prevented it from being released onto the market once it was done. This was because Woodhead had decided to program the game in the newly released Apple Pascal language (based on UCSD Pascal), which couldn't yet run on standard 48K Apple IIs, without an Apple language system and an additional 16kb of RAM. Apple teased that it would eventually release a run-time system, to provide the proper environment for Pascal programs to be able to boot on 48k computers, but no exact timeline was given on when this would be made available to developers, meaning that Galactic Attack was stuck in a state of limbo.

Nevertheless, these complications didn't seem to prevent Woodhead from pushing forward with another Pascal-based project — a dungeon game for the Apple II called Paladin — with the developer trusting that the runtime system would be along imminently.

Creating Wizardry

Roughly at the time same time that Woodhead had begun working on Paladin, he also went in search of other potential projects that they could publish under the Sirotech name, leading him to get in touch with an individual named Andrew C. Greenberg — who was an Engineering student he had met at Cornell.

"I knew Andrew from PLATO," says Woodhead. "Because he was on PLATO a lot too. And we didn't really get along all that well back then. We weren't friends. We didn't hate each other or anything, but it's just like, we just found each other annoying or whatever. Mostly because we both wanted to use PLATO and when one person was using it, they only had two terminals, so sometimes there was a waiting list. So, you'd be like, 'Why are these people on PLATO when I have some serious game-playing to do?"

Despite their frustrations towards one another, the pair eventually managed to bury the hatchet by the time Woodhead had been suspended, leading the Sirotech co-founder to reach out to Greenberg in June 1980 to see if he had any ideas for games he could publish. It was at this point Woodhead learned that Greenberg had actually been working on a similar game to his own, for the Apple II, and suggested pooling their efforts — to which Greenberg agreed.

"We started talking and it was clear that we had two different pieces to the same puzzle," Woodhead tells us. "He had written his game in BASIC and my game which I had just barely started was in Pascal, but we realized Pascal was superior for a variety of technical reasons and we'd be able to get a lot more game done. And since he'd already done a fairly simple game, he already had made a bunch of mistakes, so he knew what pitfalls to avoid. He also had one other amazingly important thing. He had the name. His game was called Wizardry."

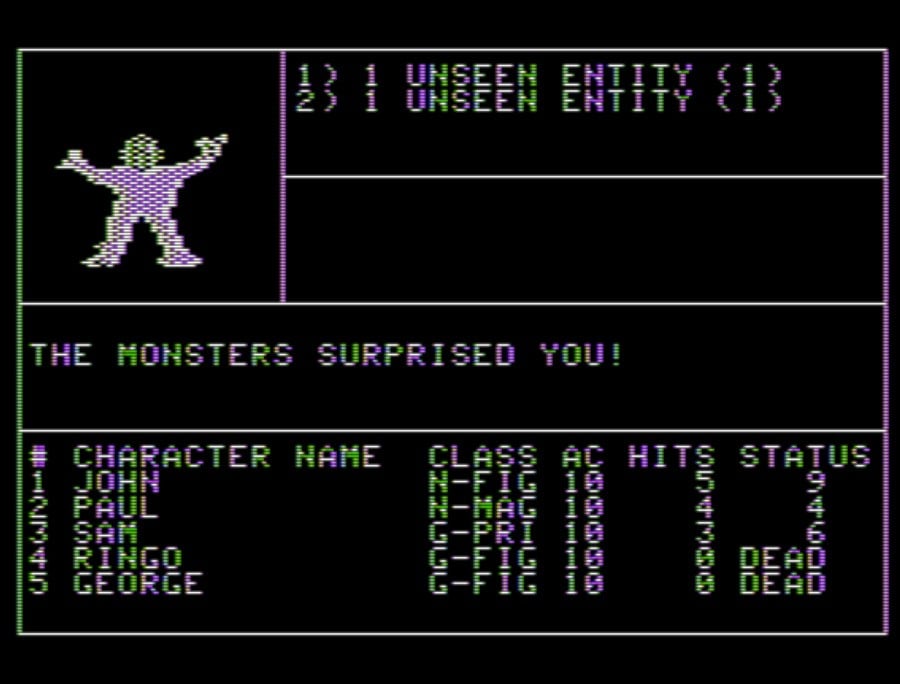

Working together, Woodhead and Greenberg began the process of rewriting the project in Pascal, reusing a lot of the design principles that Greenberg had already established — which owed a debt to the PLATO dungeon crawlers they had both played like Ouiblette and Moria. Wizardry, in case you're unfamiliar, sees players start by creating a party in the training grounds on the edge of town, with users being able to pick from 5 races (human, elf, dwarf, gnome, or hobbit), three alignments (good, neutral, and evil) and four starting classes (fighter, mage, priests, and thieves) to assemble a team of six characters. From there, they would then be able to pay a visit to Gilgamesh's tavern on the castle grounds, where they could recruit these characters to their team, before adventuring into the depths of the castle's dungeon to battle monsters and search for loot.

In the original game, there were 10 levels in total to explore — each of which was displayed from a first-person perspective — with every one of these floors being significantly harder than the last. As a result, it was not expected for parties to take on all of these obstacles at once, with players instead being encouraged to regularly retreat back to the safety of the castle grounds, to level up and heal at the adventurer's inn, purchase new items, weapons, and armour at Boltac's Trading post, and resurrect their dead party members at the Temple of Cant.

I don't know which one of us came up with Trebor and Werdna. It might have been me, because — let's put it this way — the dumber it is the more likely it is to be my work.

Despite the game's dark fantasy setting and punishing difficulty, Wizardry would end up featuring a lot of playful humour and in-jokes from its creators peppered throughout, with one of the most famous examples being Woodhead and Greenberg's decision to use anagrams of their own first names for the mad overlord Trebor and the evil wizard Werdna.

"I don't know which one of us came up with Trebor and Werdna," says Woodhead. "It might have been me, because — let's put it this way — the dumber it is the more likely it is to be my work."

Just a few short months after Woodhead and Greenberg started their collaboration on the game, the pair managed to get a version up and running in September 1980, but it was still far from done.

Not only was the game still full of bugs, but they were also still waiting for Apple to release the runtime system that allowed programs written in Pascal to work on 48K machines. So, in the meantime, they got to work fixing the issues with the game and gave Wizardry its first-ever outing at the New York Personal Computer Expo in November 1980, where they accepted the first orders for the game from paying customers.

It was during this time that many of Greenberg's friends would also end up playtesting the game, with two of these testers Paul and Helen Murphy later providing their surname to one of the game's most iconic monsters.

"Murphy's Ghost was a reference to friends of Andy's who lived in the same dorm with him," says Woodhead. "Andy lived at a special dorm at Cornell called Risley. And Risley was basically kind of focused on the performing arts. It was this really old building, and so everybody at Cornell who was into performing arts really wanted to stay at Risley. So he lived at Risley and all of his roommates and floor friends knew he had a computer. And that was kind of a rare thing, so he was a popular guy. And because people like to play games, when he started writing this game, it was only natural that his friends would test it and play it and tell him how good — or bad — it was. I think the nickname for them was WARG — the Wizardry Advanced Research Group."

Doubts, Demos, & Early Reviews

As the Wizardry Advanced Research Group continued to put Wizardry through its paces, in early 1981, Apple finally released its runtime system for Apple Pascal in 1981, leading to the release of Sirotech's first two products — Info Tree and Galactic Attack via mail order. It was at this point that two noticeable changes occurred within the company. The first is that the company altered its name from the pun Sirotech to Sir-Tech — to prevent people accidentally calling the Sirotek home at all hours of the morning — and the second is that Robert Sirotek, Norman's older brother, came on board as a marketing director to help give the Norman a helping hand.

Prior to coming on board, Robert Sirotek had been working as a programmer at a large minicomputer company but had become disillusioned with the job and the bureaucracy surrounding it. So, he decided to join his brother, who had started to become overwhelmed with administrative duties. His first role at Sir-Tech was to get better acquainted with its company's product line. This included titles that were still in active development, like Wizardry, which he believed to be a fantastic product.

Worth noting is that while Robert Sirotek saw Wizardry's potential, he seemed to be the exception among his family. His brother Norman and his father, for instance, had both expressed concern at how long the game was taking and tried to talk Robert Woodhead into focusing on business-related software instead, believing the market for Apple II games to be too niche to turn a sizeable profit.

“I guess I was guilty of some conventional thinking,” Norman told Softalk in August 1982. “I remember late one evening telling Bob Woodhead to forget the new game and put his efforts into something worthwhile, like a business package. I said nobody wants or needs the game. Bob looked straight at me and said I was wrong and went back to work.”

Fred Sirotek, meanwhile, told Softalk in the same issue: "The boys thought that it was a great game, but as far as I was concerned, computers were business machines. They weren’t fun machines. You do things with them that you need. I certainly did not realize that there is such a relatively large segment of the population that has the computer only or mostly for pleasure."

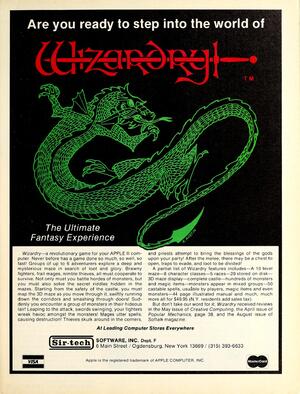

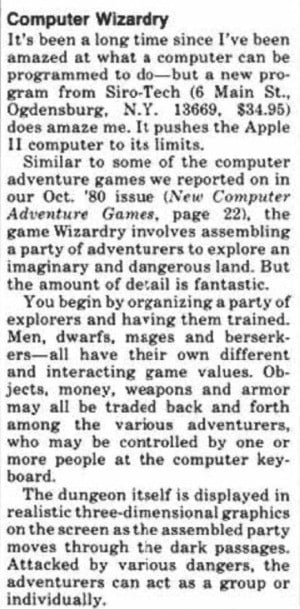

Fortunately, most of these doubts eventually subsided in the run-up to release, as Sir-Tech began to step up its marketing campaign and get more feedback from the press and members of the public. In April 1981, for instance, the journalist Neil Shapiro wrote in the science and technology magazine Popular Mechanics that Wizardry "pushes the Apple II to its limits" and speculated that it could "open up a whole new realm of programming." This was then followed, one month later, with an equally glowing report from Creative Computing's David Lubar, who called Wizardry "an excellent program" and a "good investment for anyone in need of a dungeon master".

Things seemed to be falling into place for Wizardry to become a hit for the company, with Sir-Tech even publicly discussing the possibility of new scenarios, but before the game was ready for a widespread release, Robert Woodhead wanted to get some more in-depth feedback from potential buyers to help iron out some of the remaining bugs. So he came up with the idea of releasing a test version of the game at the June 1981 Boston Apple Fest.

"Back in those days, you had so many different computer configurations that you could put into your Apple II, like Legend cards, other kind of memory cards, and so forth," Norman tells us. "And we could not test every conceivable combination. It was just physically and mentally impossible. So he wanted to release a beta product into the market for testing purposes. And his attitude was, 'Why don't we go to the Boston Apple Fest show? We'll sell a couple hundred copies, they'll pay for the show, and we'll get some feedback from users about the game bugs and configuration problems.' So we agreed and packed up the van."

One of the interesting facts about the version of the game that was sold at Boston Apple Fest was that it wasn't exactly "playtest-balanced". As Woodhead recalls, upon entering the dungeons, players could immediately encounter the devil on level 1, causing their entire party to be wiped out almost completely. This served the functional purpose of allowing players to be able to test more of the game, without having to descend into the deeper levels.

"Our name for it was the Dungeons of Despair," says Woodhead. "Because you would seriously lose your cool playing the game. I seem to recall that we promised people we'd send them the final version of the game when it came out in return for them letting us know if they found any problems. We also didn't make that many copies because we had to make them by hand."

According to the Siroteks, the Boston Apple Fest ended up being further evidence that Woodhead and Greenberg were on to a winner. All they needed to do now was add the finishing touches and squash the final few bugs that players had reported. While they did this, the positive press continued to roll in, with Softalk publishing a review in August 1981, where it called Wizardry "the truest of all programs to TSR's noncomputer Dungeons & Dragons" and an "imperative" purchase for fans of the table-top roleplaying game (at $39.95). It would later be released one month later, in September 1981, with the game being shipped in a premium-style box with a manual, as opposed to the regular Ziploc bags most Apple II software was distributed in at the time.

The Big Release & Wizardry's Legacy

Much as the early press and publicity foreshadowed, Wizardry very quickly went on to become a huge commercial success for Sir-Tech, selling a reported 24,000 copies in its first year (according to the September/October issue of Computer Gaming World). For Fred and Norman Sirotek — who had previously tried to talk Woodhead into dropping the game — this was clearly quite a humbling experience, with memories of his prior conversation still ringing in his ears.

"Two months after Wizardry came out, I was ready to eat my hat!" Norman told Softalk in August 1982, continuing, "I’m glad I wasn’t more convincing with my argument."

In the wake of Wizardry's success, unofficial "cheat" programs started to appear on the market to capitalize on the game's popularity, allowing players a greater level of control over their characters, such as the ability to raise them from the dead and alter their levels and loadout. This was something that Sir-Tech actively discouraged, even going so far as to threaten to void people's warranties if they were caught using them.

"We spent an absorbent amount of time debugging and play balancing Proving Grounds," says Norman. "And when these cheat programs came out, they were designed to change the strength and the armor class of your character.

If all of a sudden your characters were super strong, you're just gonna march through the dungeon. You're not gonna care who you run up to. There's no longer the fear of your characters dying. And that took away a lot of the finesse of what Wizardry is.

"The best way to put it is when you go down into the dungeon and you play the game, you have this sense of tension. Am I gonna make it back out alive? How far do I go? How many steps into the maze do I take? And it's forever a calculation of survival. That creates playability and that creates tension. Now, if all of a sudden your characters were super strong, you're just gonna march through the dungeon. You're not gonna care who you run up to. There's no longer the fear of your characters dying. And that took away a lot of the finesse of what Wizardry is. And so, our thought process was, 'Okay, you modify the characters, we're not going to warranty it, period.' It was really a game balance issue more than it was, 'You broke the disc, we're not going to honor the warranty.' As a secondary item, some of these utilities did break the disc. They messed up the code."

Interestingly, these weren't the only unofficial products being released either, with the game also later receiving an unlicensed strategy guide called Wizisystem that aimed to guide "the average player" with "neither the time nor the means" to complete it. If all of this wasn't evidence enough of what some in the media had already started referring to as "The Wizardry Phenomenon", soon stories began to appear about a child psychiatrist in Williamsville, New York using Wizardry to get his patients to open up, as well as English Wizardry players coming up with tournaments that saw participants competing to collect the most gold in a fixed time-limit.

Buoyed by all of this success, Woodhead and Greenberg immediately got to work on making a new revision of the game, as well as developing a sequel scenario, Wizardry II: Knight of Diamonds (which would be released the following year and require players to transfer their party over from the original game).

It was around this point, in 1982, that a small Tokyo-based company called Starcraft also approached Sir-Tech with the idea of marketing and distributing the game in Japan — to which the publisher agreed. Starcraft's plans for the game weren't to produce a costly Japanese localization but to simply make the original Apple II version more widely available in the country, and remarkably, this strategy seemed to pay off with the game reportedly selling $30,000 to $40,000 worth of programs a year in Japan, according to the Associated Press.

Among those who reportedly played this version of the game were the father of Final Fantasy Hironobu Sakaguchi and Dragon Quest creator Yuji Horii, both of whom would later go on to incorporate elements of what they loved Wizardry into their own RPGs.

As Robert Sirotek states, "We didn't really closely monitor what he was doing in terms of promoting it, but he was moving volume considering that it was 1982. So that kind of evolved as the years went by, and in 1984, ASCII Corporation, the creators of the MSX, approached us and they wanted it localized. So essentially what we did is we wanted to maintain control of the quality of the product and so what we did is we made an arrangement where we were responsible for porting it to the various platforms that were popular in Japan, localizing it with Japanese language and the various dialects, and it was important to do that in Japan. We didn't want to hire a bunch of translators in North America who didn't understand all of the particular nuances of the language."

Rather than simply stand aside and let the Japanese developers do all the work, Sir-Tech ended up partnering with a Japanese form called Foretune (owned by an individual named Shigeya Suzuki) to create translated versions for Japanese computers like the FM-7, PC-88, PC-98, and Sharp X1, with Robert Woodhead taking a trip to the country to assist with this effort.

"I literally spent months over there," says Woodhead. "They basically wrote P code interpreters so they could run Pascal on all the different machines and my main contribution was to abstract all of the textual information into a language database. Basically, what would now be called a localization file, but this was, I think, one of the first times it had been done. Then once that was done, all they had to do was edit the localization file to include the kanji and kana, and the game was up in Japanese. And of course, they had to redo the graphics for each of the machines too."

With sequels and ports to other platforms hitting the market, the popularity of Wizardry exploded even further in the country, leading to even more versions for other platforms (including most notably a version for the Nintendo Famicom/NES).

Following the incredible success of the first Wizardry game, Robert Woodhead kept working on the series until 1987's Wizardry IV: The Return of Werdna, later going on to start the anime licensing company AnimEigo in 1988, with Roe R. Adams III (who was also a co-designer of Wizardry IV).

Andrew C. Greenberg, meanwhile, ended his direct involvement with the series after Wizardry V: The Heart of the Maelstrom, starting his own publishing company Masterplay Publishing Corporation in 1988, before going back to university to train as an intellectual property and technology lawyer. He, unfortunately, passed away earlier this year, with Robert Woodhead posting the following message in response to the news: "It is with great sadness that I mark the passing of my dear friend, the Evil Wizard Wedna."

As for the Siroteks, they still own the rights to Wizardry 1-5, and recently licensed the IP to Digital Eclipse to create a remake of the original game. This remake features updated graphics, audio, and a range of customizable options to toggle between the original "hardcore" rules and a more modernized set.

Reviews of the game so far have been mostly positive with our friends over at Nintendo Life, giving it an 8/10 and calling it a "stylish and subtle retooling of a classic".

Though it's been forty-three years since the game was originally released, the Wizardry series is still going strong, and winning over new fans — many of whom were not even alive when the game was first launched.