Don't worry – you're not suffering from déjà vu. If you feel like you've read this before, it's because we're republishing some of our favourite features from the past year as part of our Best of 2024 celebrations. If this is new to you, then enjoy reading it for the first time! This piece was originally published on April 9th, 2024.

You've probably heard of Ride to Hell: Retribution, released on PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, and Windows back in 2013. It's regarded as one of the worst games ever. On our sister site, Push Square, it has a user rating of less than 3. Metacritic aggregates a critic rating of 19 out of 100 and a user score of 1.3. There's also a plethora of YouTubers with comedic videos pointing out its flaws (TehSnakerer nicely covers the entire game in 30 minutes). Some reviewers joke that the 1% on the cover actually represents the game's true score. But we're not really here to talk about Ride to Hell: Retribution, since it's actually sort of a remake; we're here to mourn the cancellation of the original Ride to Hell, which looked phenomenal. Despite sharing a name, the two are completely different games!

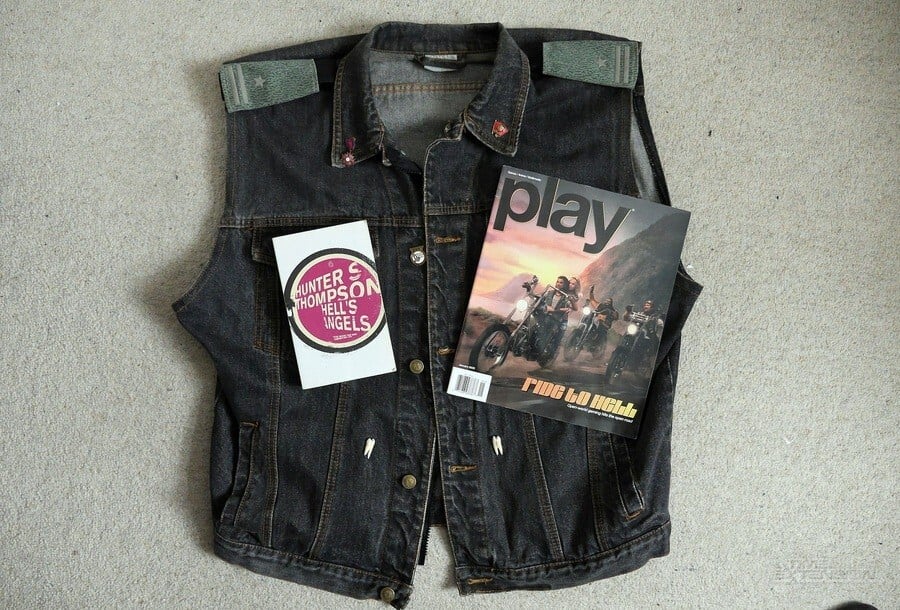

Your author first came across the original thanks to Dave Halverson's multiformat Play magazine, which made it the cover feature for issue 85, arriving December 2008 via subscription. Brady Fiechter's exclusive preview described the Big Sur in California and the landscapes of Nevada, mentioned Hunter S Thomson's seminal Hell's Angels book, and examined an open-world biker gang simulator which promised authenticity and freedom. As far as previews go, it was captivating. Your author had travelled those open highways, read Thomson's books, and even owned the requisite denim jacket (though only two of the three airman's wings). The freedom touted by Ride to Hell was intoxicating. For context, that same issue, they previewed Heavy Rain and reviewed Left 4 Dead; it was an optimistic time.

To fully appreciate what that game promised, one needs to internalise and really feel the zeitgeist of this long-past era and way of life. The 1960s in America were a time of counter-culture revolution, of liberty and free love, before computers, mobile phones, and satellite surveillance. You could lose yourself in the vastness of its geography, riding desert roads drenched in sunshine with snowy mountains on the horizon. Bikers meanwhile represented perhaps the last vestiges of the pioneer spirit and horse-riding trailblazers - not quite nomads, but outside the norms of then-contemporary society. They embodied freedom of movement, thought, and spirit. Ride to Hell aimed to replicate all of this as much as possible - though it was compared to GTA, it promised something distinct.

Of course, Ride to Hell never came out. It was cancelled, and then in 2013, a pseudo-remake subtitled Retribution was released instead. Development was credited to Eutechnyx and a long list of subcontractors totalling over 300 people; the publisher was Deep Silver. None of the staff mentioned by Fiechter are credited in the remake, making it impossible to know who worked on the original. In a way, Fiechter's article is like a Rosetta Stone, offering clues to follow. He'd spoken with Hannes Seifert, executive producer, and so we tracked Seifert down for an hour-long chat.

For those who didn't follow the original, it would have pushed the then limits of open-world sandbox adventures (conceptually, it started in 2006). Set over 95 square kilometres of map, based on real-life satellite terrain data for California and Nevada, players would have had total freedom to ride anywhere they pleased from the start. Instead of currency you earned respect through various actions - securing a gas station or diner would expand your sphere of influence.

There would be melee combat initially, some gun combat later, plus bike-on-bike combat. Other drivers would have organic AI that interacted with each other (an angry trucker smashing a Sunday driver, for example). For the music, 300 songs from the era had already been licensed. Fiechter described a lot: weather, lighting, physics, customisation, freedom in defining yourself, so many neat little touches. Fiechter's vivid descriptions, in conjunction with previews from other publications, portrayed a game almost overwhelmingly promising. According to Fiechter, the team were also influenced by the Zelda series, even naming their demo room "Hyrule".

"Yeah... I mean, yes... because..." laughs Seifert mid-sentence, perhaps a little uncomfortable at the level of emphasis we placed on the question. As he explains, there was a lot more influence than any single game, "I worked as executive producer on GTA III and Vice City, and other open world games later, like Dead Island and so on. Of course Ride to Hell is heavily influenced by this previous work in many ways. We also used some of the same production partners, like Perspective Studios and so on. In my book, the first real open-world game of that kind was The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. But to add to that, my first open-world experience as a player was Elite. But that's different, right? But when you're sat in front of your Commodore 64, and your screen is like this window into this vast universe, it was fantastic for me."

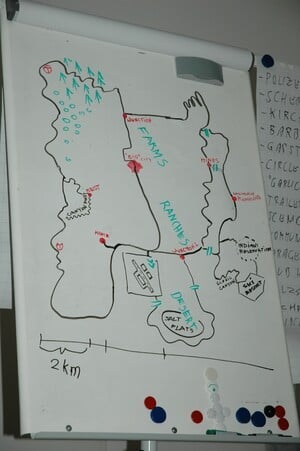

As an executive producer, Seifert discusses game development in clear business terms. There's a more serious tone compared to, say, an artist or musician. But discussing the history of games, as above, reveals someone who genuinely cares about making good games and, at heart, still appreciates the inherent joy games can provide. It's evident the original team were having fun, too, and creating something they believed in – like when Seifert sends over a JPEG showing potential map locations.

"I found a private photo from our very first brainstorming session," he explains. "I was laughing when I saw the date stamp. We did that on June 6th, 2006, which I found hilarious in the context of biker culture and 666. <laughs> As this photo predates the company, I can share it with you. I hope it's fun for your readers too."

Some sites like IGN and GameTrailers had video interviews with Martin Filipp (developer relations manager), but the rest of this team was a mystery. So we asked Seifert for names as a permanent online record. He replied, "I was trying to get together names and companies from the original team. Please mind this is by no means complete, I was looking through some old personal notes for this, too. I hope I didn't forget anyone. There was no other 'Deep Silver' company at the time, only Vienna. So Koch Media was the publisher. Bob Bates wrote the script, it was based on Hunter S Thompson's book, Hell's Angels, but also on the autobiography by Sonny Barger. I think we captured the authenticity pretty well, and the story and cut-scenes delivered that. The character design by Massive Black was also excellent. These were people who really had a strong relationship to the '60s and the mid-west, and it helped us to create this atmosphere in a very good way."

Core team:

- Chris Soukup (technical director)

- Darren Lambourne (sound and music)

- Gunter Hager (game design)

- Helmut Hutterer (level design and QA)

- Johannes Mücke (art director and concept artist)

- Julian Kenning (art director)

- Marin Gazzari (producer)

- Niki Laber (business)

- Hannes Seifert (executive producer)

Some partners:

- Andy Mucho (sound engine)

- Aurona (Characters)

- Bernhard List (Cut scenes)

- Bob Bates (screenplay and dialogues)

- Dynamedion (video audio production)

- Enyzme (QA)

- Eutechnyx (main dev partner)

- Havok (physics)

- Inkstories (casting, cutscene directing)

- Massive Black (concept art)

- Metric Minds (cut scene cleanup)

- Perspective Studios (motion capture)

- Rabcat (character reworks)

- Realtime UK (trailers)

- Ultizen (Characters)

As we chat with Seifert, it dawns on us that over 20 people spent several years of their lives, at least 60 cumulative human years, creating something that vanished. Maybe even a century's worth of time. Documenting their names for future researchers is important. But how did this project come about?

"To give you a little bit of background," begins Seifert, "Back in 2006, my long-term business partner, Niki Laber, and I were talking. It was after our work at Rockstar ended. When Take-Two restructured and closed the studio. We got permission to start something new, and we wanted to start a new studio, but we would never start without a vision for something. We're not people who start companies to start companies - we always wanted to do something specific. The company we founded after Rockstar was called Games That Matter, and we founded it in 2006, based on the concept for Ride to Hell. So Ride to Hell was a game that we worked out in 2006, together with a couple of people that I mentioned. Back then it wasn't Julian Kenning yet, but it was myself, plus an art director and concept artist called Johannes Mücke. Also Niki Laber and one or two other people."

At this point it's worth noting Seifert's background. His MobyGames profile with 26 credits is only half complete. The resume he sent shows 58 entries, starting with making C64 games in 1987 - in fact, the Museum of Science and Technology in Vienna showed his old work as part of the history of video games in Austria! Later highlights include various producer and managing director roles on the Max Payne trilogy, GTA III and Vice City, Dead Island, Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days, and multiple entries in the Hitman franchise, including the well-received 2016 release. It's important to know these because it reveals Seifert's ability to ship finished triple-A products that review well - and to distance his cancelled version of Ride to Hell from the remake.

"I think it's always good to have a mix," interjects Seifert when we mention his portfolio and the experience of the team. "I like veteran game developers, like myself - I've been doing this for 37 years. But you need the fresh blood as well. You need people who are not burdened with the limitations or the limited thinking that you had when you had 60k of memory. Nowadays, you can't even fit a mouse pointer into this memory. So it's a different way of thinking."

Games That Matter was part of what Seifert calls the Hollywood production model of games, which he's described at GDC and other conferences. "The basic idea was to have a production company," he explains, "And that company founds so-called Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV). Meaning companies that are only dedicated to producing one game. And the first game we produced with this model was Ride to Hell. We looked for production partners to make that game, with Eutechnyx becoming one. Eutechnyx is a work-for-hire company. We had a really good work relationship, spent a lot of time with them in Newcastle. A good bunch of people. Technically very savvy. But they never really shipped something creatively, mostly doing racing games. Which they didn't do badly. The game they created - which worked for us as a foundation for 'hey, we could do Ride to Hell with them' - was their MTV Pimp My Ride interpretation, where they had the game engine for the open road, and the vehicle dynamics, and things like that."

"So the idea for Ride to Hell," adds Seifert, referencing the earlier staff lists, "the first basic concepts and game design, that was done with a small group, like five people, and with that, we went out to pitch to get funding. Either fund it ourselves or with a partner; the basic idea is this SPV could be owned by a publisher, or venture capitalist, and part of it is owned by the production company. That was the business model of Games That Matter. We went out to pitch and had a couple of interested parties, and one of them was Koch Media. What happened was - and this was not planned - but Games That Matter was bought, I think seven months after we founded it, by Koch Media. They renamed the company Deep Silver - before, it was only a label, there was no company called Deep Silver. We built it up, and I think we grew to 20 or 25 people, managing three projects. Cursed Mountain was one of the projects that shipped, Dead Island was another that shipped, and Ride to Hell did not ship in the end."

We spend a lot of time going over which companies handled what, since Eutechnyx is listed as the main creative force behind the Retribution remake, despite joining the original project primarily for its technical muscle. Searching online, the roles of subsequent companies are vague. As Seifert describes events, we're going to reach an ironic and terrible conclusion - brace yourselves.

"We provided the art, and the writing, the voice recording, the casting, the design; the level design and the mission design, and so on, together with Eutechnyx - we worked on this for a couple of years," Seifert continues. "I think we could have made more progress with them, so it was perhaps too big a product for our production model. It was a challenge; it was the first one we did. I think Dead Island is a better example, where we found a better set-up. That worked pretty well. Dead Island was finished less than a year after I had resigned. Work commenced years earlier, I think in 2007 or so. So that was pretty far along when I left. Ride to Hell was far-ish, but it wasn't far enough, and then they decided to do a different kind of game - I think because they just didn't want to invest more money in it, but they didn't want to give up on it."

The remake ditched the original's open-world design, meaningful bike customisation, story of alienation, voice recordings, diverse missions, dynamic weather, organic driver AI, respect-based currency system, 300 licensed music tracks, beautiful art design, subtle lighting... actually, it's easier just to say they junked everything. Seemingly every aspect of the original was binned and restarted, apart from a few token names. This remake suffered from poor physics, glitches, nonsensical level design, and the most freakish oversized hand-to-head ratios ever seen. Most offensively, though, it was just boring. It felt so obviously cobbled together in a hurry.

But of course, Seifert had left the project before its cancellation and rebirth, and his core team's names and work were erased. How did he feel about what they had done to his baby?

"Eutechnyx showed me that new game once, while it was still in development," he replies, very politely. In fact his entire demeanour during the interview is cordial and without negativity. However, he does acknowledge its shortcomings, adding, "It was very different. They actually finished it and shipped it. But I talked with Brian Jobling, who was the [Eutechnyx] CEO at that time. And I said, look, I think if you ship it like that it might be a reputational stain on your track record. So I have no other visibility - I know the final game, I know they changed it. They even changed the game engine. Eutechnyx had its own really good engine, for open world systems, and we had some really nice lighting, and weather systems, and vehicle systems, and then they changed it to Unreal 3, and did something completely different with it."

This revelation hits like a bombshell. Let's recap: Games That Matter was formed to bring about this vision for a 1960s-era open-world biker game, allowing total player freedom, and Eutechnyx was brought on to provide the engine, which it already had, and technical expertise. Looking at its portfolio reveals the company worked almost exclusively on the properties of others - no original creativity. Then, after Seifert left and Deep Silver Vienna was shut down, it being the creative side of the project, Eutechnyx was tasked with completing the project and taking on the creative side, and then the entire reason for Eutechnyx coming onboard - its fabulous open-world game engine - gets scrapped for Unreal 3. Rather than blaming the team, you can feel sorry for Eutechnyx; it was presented with an opportunity, and then midway, the rules and goals were changed by the publisher, Koch Media.

"I think my regret is that my decision to leave led to this not being finished," says Seifert, reflecting on the loss. "Because I think it would have been great to finish. What happened is we shipped the Wii game Cursed Mountain in 2009, and I would say we had 'strategic differences' on how to market or publish a game. It was the first game we shipped together, and we were pretty unhappy with it. And in that year, I got headhunted into Square-Enix, and I accepted that job, so I resigned in December 2009. After I resigned, they decided to close the company, a couple of other people left. Actually, my partner Niki had left half a year earlier out of different but similar frustrations. Then Koch Media continued with Eutechnyx, and they changed it - I think they lost all the people who were the creative leaders on this."

This brings us to the 2013 release of the Retribution. It pains us because the original showed so much potential. Viewing the press shots and gameplay footage hints at what could have been, and what's shown looks so tantalisingly glorious. But, of course, press shots and pre-alpha footage are curated. In our hearts, we know these can be misleading. So we close our eyes and ask Seifert to describe what was actually playable - to play the game vicariously in our imagination.

"What we had was the whole environment, the whole world. And we started populating it with missions. We had the road network, most of the weather systems. Almost none of the art was finished. So pre-alpha means you cannot play the entire game, and most of the art was actually placeholders. We had a fairly elaborate motorcycle editor. Because that was the character in the game - the character was not the main character; it was your motorcycle. You could modify it from the frame upwards. The user interface of the editors were still a bit flaky, stability was an issue, most of the missions were not fun yet. I think we had all the cut-scenes in the game. Again, with unfinished art assets. In an open-world game, you don't create a level as a vertical slice - you create a small sub-part of the vertical slice. So we had some part of the road and some part of the town that was connected to play missions. That's the one that you could play, when you take the old build and put it on an Xbox 360 dev kit. I can't remember which mission it was - we had so many different missions. But one involved some motorcycle fighting because that was something we needed to prove; it was bike-on-bike fights, which is pretty difficult. And some character navigation, and some cut-scenes. So playable? Absolutely. Enjoyable? Not yet."

Unreleased games do get leaked - and sometimes unfinished games even have fans completing the work, such as with the original Duke Nukem Forever. The hope of someday experiencing the original Ride to Hell is strong. Seifert confirms the data ran on Xbox 360, which he focused on, and also PlayStation 3, though he was unsure if a PC version was actually available. The lead systems were the consoles; presumably, if anyone leaked the data, it would require modded systems (which we have, luckily). Given that this may never come to pass, we pressed Seifert to share more - what did he personally enjoy when playing the original?

"I really enjoyed navigating the landscape. It was not procedural, the landscape was based on satellite data from California - well, California and Western Nevada. And we cut these together. So there's some elements, like the Big Sur, for instance, and others, like the 'Mount Puma Observatory', which was based on the Mount Wilson Observatory. A couple of these things felt very nice riding through, with the lighting technology that we used. The landscape felt very authentic. I've been driving around that area, and hiking with my wife, and it felt authentic and it was relaxing. Particularly in combination with the music we had. So that's something I liked, with the motorbike physics."

Ahh yes, the music! Did they really license 300 tracks? Could he perhaps provide a document listing all of them?

"I don't think I have that. Koch Media bought us and was our partner, and Koch was originally a music company, and they were sold to Universal, and then we got all these licenses from Universal. And they had a huge back catalogue we could use. And actually, Born to be Wild, I personally never really liked that as a track for Ride to Hell, because it's a little too cliché. But you couldn't get some of the music - like Jimi Hendrix you could not get, period. It's like it just didn't get licensed for games. So we were limited to the Universal back catalogue, which was pretty great in many areas. And that was all in the game. I don't know why they didn't use it - it might not have fit, because the new game just has a different vibe. It has a different look, and more violence. Overall a different setting, because it's all about this retribution. We were more inspired by movies like Hells Angels on Wheels (1967). You know, things like that. Biker-exploitation flicks. It's a bit more light-hearted."

We again press Seifert for personal descriptions. The more we hear, the more it feels like the world lost something truly special in its cancellation, and these words might be the closest anyone gets to experiencing it.

"What I really liked to play around with, a lot, was the bike customisation," adds Seifert, graciously indulging our request. "Because you could really create great bikes. Like almost anything you wanted to create. We even had things like stencils and decals on it and everything. It was really limitless. It was a bit like modern character generation - when you create a character in a role-playing game, but with motorbikes. Doing that was a time-sink because it was really fun."

The game's 'photo mode' was also a highlight. "So you could take a photo and actually share it on your Xbox 360, on Live, with other players," explains Seifert. "It was just a small size, I think with a limit of 100kb or something, and we used the low quality as a design element because, at that time, it was like a Polaroid, right? So you use your Polaroid, and you have an instant photo, and you could photograph your bike and the landscapes and the sunsets, and there were some mini achievements. Like you could photograph a shooting star, which we also had in the game. And that would give you a unique achievement. And that I really liked."

Finally, Seifert praises the visual look of the game. "The customising of the bike, moving somewhere in the landscape with it, and then placing it in a nice environment, in specific weather and light, that was fun. Even in that early stage I really enjoyed that. Because of the lighting, and the weather, and the landscape, and the feeling of distance and mist and all this, it didn't matter that the art was non-existent in some areas. In most areas. But the landscape was there. There's not many games where I can get that. Perhaps Oblivion had this, in some areas. But of course, that's fantasy, so it's different. This one was relatable."

For anyone who played Vice City and would find a scenic area to listen to their favourite 80s song, simply to luxuriate in the atmosphere of it all, these descriptions should resonate strongly. But this atmosphere and the story is only part of the game experience, the other intrinsic part being the mechanics or gameplay. How did the missions play? Does he still have the design documents?

"I don't know!" laughs Seifert. "I don't think so, because when I leave, I am normally very diligent with deleting everything. But this was still a time when things got printed. So perhaps there is something somewhere on paper. I don't think I have it, but even if I do - I can use it to refresh my memory, but I could not share it. Since this is the property of Embracer now. I need to be mindful of that. Gunter Hager was our design lead. I think the mission structure was mostly myself. We were a team, we had a couple of people, and we definitely worked on the missions together. The entire team worked on missions, and then we provided this to our partners at Eutechnyx. But the actual story of the missions, how they connected, we did this mostly with the team in Vienna."

It's at this point that Seifert gazes at the aforementioned Play magazine cover. "I'm looking at the image used - that's, of course, painted by concept artists. But it's based on in-game assets, the area around the Big Sur. We had the Western coastline there, and you could ride in a gang - so for some missions, you needed to ride together, and that's what you see there. This is not a bad image of the memory I have of it. This is Candy sitting behind him, and there are other characters. They all had specific roles. Like Doctor Blotter, as the name says, was kind of the resident drug professional in the team, so could heal you and things like that. Blotter, like what they used for LSD. <laughs>"

The original concept began 18 years ago, while the 'remake' came out 11 years ago. It did not fulfil the ambitions of Seifert and his original team. Since Retribution's release, there's been seemingly no interest in revisiting the concept of open-world bikers. Not only was it a wasted opportunity, we wonder if Retribution didn't poison the public's collective consciousness a little? Journalists would inevitably compare any subsequent game to Retribution, thus immediately tainting it by association. So we ask Seifert, with hindsight, does he feel his version could have succeeded?

"<laughs> Oh, that's a tough one!" he sighs, adding, "As a developer, it's normal to start way more games than you finish. That's just part of the work. The competition could do something; your budgets could change; games get cancelled all the time. Most of the games that get cancelled are never made public. I believe it could have... at that time, there was this resurgent wave of biker culture. When we started, it was a hard pitch. Because motorbikes, particularly in Europe, and particularly Harley, were perceived as something for old people. That changed while we were developing. Hell Ride, the Quentin Tarantino production, and then Sons of Anarchy came along. There were a couple of things around the culture that really reignited it. A lot of '60s revivals at that time used the culture of the '60s in a modern context. So it would have been a good opportunity. While we were working on it The Lost and the Damned came out, from our previous employer, which was also set in the motorbike scene. It was just an add-on for GTA, but still, it was a good thing! It's hard to say how the original Ride to Hell would have done on the market. But I believe the potential was definitely there."

Ultimately, Seifert feels it's a shame that the original vision for the game never happened. "The desire for open-world games was very big, and people still like this style today. Obviously, this is an old game, and back then, we would never have reached the density of what you see nowadays in things like Elden Ring or other games. It was a child of its time, but I was still sad at never having shipped it. I may have worked with many games with a strong story, but this one, it had something really good. The writer was also of that generation, which made it even better. It had a good tone for the characters. I would say I'd like to ship it today - but who am I to judge whether it would be successful. You never know, right?"

Seifert's recollections are so detailed and rich we've only been able to quote some of them. There is so much to say on this lost game, and still more to uncover. But we leave you with Seifert's final message.

"If this will be read by other developers, I would say: never be discouraged by something like this. You never know when you'll have an opportunity to do something again. I was dreaming about creating an episodic Max Payne, forever, and then I was able to realise my vision with Hitman 2016. And you never know when the time is right. I think Ride to Hell is one of these examples. Perhaps it was a really good idea, but perhaps it wasn't its time yet. Who knows what will be in the coming years or decades. Perhaps someone picks it up, perhaps it gets revitalised. This is a very vivid industry, and a lot of things come around."