Don't worry – you're not suffering from déjà vu. If you feel like you've read this before, it's because we're republishing some of our favourite features from the past year as part of our Best of 2024 celebrations. If this is new to you, then enjoy reading it for the first time! This piece was originally published on February 22nd, 2024.

With the recent passing of Yoshitaka Murayama, the world has been robbed of a creative visionary. Friends and family have lost a loved one; fans of his work have lost an auteur they could trust; a younger generation of developers have lost a sensei they could learn from. Murayama can never again discuss his craft and so, his words we now have are all we'll ever have. This final point is particularly salient since, as will be shown, Murayama had a strong understanding of player needs.

Murayama's best-known works are obviously the first two Gensou Suikoden titles on PlayStation (there was a Saturn port of the first; both were ported to PC) and his initial work on the third game for PS2. But he was also in charge of 10,000 Bullets on PS2, a criminally overlooked gem of an action game, mixing the style of Devil May Cry with the bullet-time of Max Payne. More recently, Murayama was involved with Eiyuden Chronicle: Rising and the yet-to-be-released Eiyuden Chronicle: Hundred Heroes. Plus, as covered previously, Murayama was part of the secret internal team developing a console at Konami.

Although his portfolio is comparatively small, the first two Suikoden are timeless masterpieces and represent some of the absolute best the JRPG genre offers. This is evidenced by the first regularly topping £100 for sold auctions, while the second goes for more than twice that! When researching The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, your author was fortunate enough to interview Yoshitaka Murayama, kindly facilitated by Harry Inaba and Jeremy Blaustein, localisers on the first and second game, respectively. Inaba gave some insight on the first localisation, joined by Blaustein and Casey Loe on the second. It came to 6'400 words over 13 pages, going in-depth on the creation of the games.

Given Murayama's passing – and Konami's HD remasters looming – please enjoy this feature. All quotes from Murayama are from original research; we've provided links to further reading and other interviews.

The first two games are timeless masterpieces, and we hope more people get to experience them.

It Started With A Sequel

Yoshitaka Murayama's initial plans, surprisingly, didn't actually involve game design. He joined Konami as a new graduate in 1992, filling the role of programmer. He must have impressed management, though, since they quickly elevated him to a new project.

"In my second year after joining, I was put in charge of creating games for Konami's game machine, and that's when I got involved in game design," he told me back in 2013. "Since it was an extremely secret project inside of Konami, there were very few people involved. So, even though I was close to being a new recruit, I was expected to play a very large role. The plan at first was for Konami's game machine to be a console, and it was suggested that it have a card reader function to allow players to exchange data. The plan changed midway from a console to a portable machine, and it was going to have 3D (polygon) functionality, which was uncommon at the time."

Murayama described Konami's new console-then-handheld as using ROM cartridges, and had the impression of being a high-class Game Boy with 3D capability. It would ultimately be cancelled after Sony's announcement of the original PlayStation, whereby Konami shifted to providing games for this new CD system. It's important to go over this history, because Suikoden has its origins here – but it gets complicated.

The first "Suikoden game" (let's call it Suikoden Zero) was planned as a launch title for Konami's ill-fated hardware, was ultimately never released, and was the sequel to the first game on PlayStation. Or, to be more accurate, the first game on PlayStation was developed as a prequel to the unreleased Suikoden Zero. For absolute clarity, Murayama never used the term "Suikoden Zero"; we're creating that name to avoid confusion, since this unreleased game is not to be conflated with the official sequel, Suikoden II, even though there are similarities.

Sources for all this come from an interview with Murayama in Swedish magazine LEVEL, specifically #41, August 2009. Pieces of this were then translated by the fan-community, and his answers influenced the questions in our own interview. In LEVEL, he described Suikoden Zero as a story of two countries at war – on the opposing sides two childhood friends. As you can see, there's already a hint of Suikoden II in the description, but we'll get to that later when analysing literary influences. Suikoden Zero was also to have 60 different character classes! Development is said to have lasted about a year. An interesting discrepancy is that in the LEVEL interview Murayama said he'd worked at Konami for about six months before moving on to the project, while in our later interview he amended this to his "second year after joining". Either way, it puts the start of Suikoden Zero's development somewhere between 1993 and 1994.

It was during this period that Murayama met Junko Kawano, character designer on Suikoden I, who would helm later entries after Murayama left (she's also the main person behind the excellent time travel PS2 adventure, Shadow of Memories). I asked Murayama about working with Kawano, and he explained: "We were contemporaries who entered the company at the same time, and we were put into the same department. In our early years at the company, we often went out drinking with our colleagues – and we were very close. Miss Kawano wasn't merely a designer; she had very strong ideas about games, and though we sometimes had disagreements about the contents of the games, it was fun and beneficial to work with her."

In addition to this RPG (Suikoden Zero) that Murayama was working on, there were other launch games being made by Konami. From his other interviews, we know there was a racing game and a versus fighting game; given how poorly documented it all is, I asked Murayama what he could recall. How far along were all the games, and did they evolve into other titles?

"When the development for the game machine was cancelled," explained Murayama, "those titles were completely abandoned. Actually, at the time, I was involved in the development of an RPG and a fighting game. The fighting game had about two characters that could be operated to a degree, and the RPG had a playable opening. Since the racing game was being done by another team, my recollection is a bit vague, but I think it was about 20% along in development. None of those titles went on to completion, but the name of the hero's best friend in the RPG I was working on was later reused in Suikoden I - that name was Ted."

Ultimately, all the games for this new hardware were scrapped, and about a week later, Murayama was assigned to create a game for Sony's PlayStation. In the LEVEL interview, he described how he and Kawano, and ten other employees, were in a meeting where Konami revealed plans for five PlayStation games: a racer, a baseball title, and three RPGs. One stipulation was that it had to be the first in a series – there was talk of competing against the RPGs of Enix and Square; Dragon Quest VI (December 1995) would still support Nintendo's Super Famicom, with Dragon Quest VII swapping over to PlayStation in August 2000. Square's change of allegiances with Final Fantasy VII meanwhile are well documented, with the three-disc epic hitting Japan in January 1997. Konami still had time and would release its own PlayStation RPG ahead of much of the competition (From Software's original King's Field launched the same month as the PlayStation, December 1994; other JRPGs which beat Suikoden to launch include King's Field II, Arc the Lad, and Beyond the Beyond).

Given the available selection, Murayama chose to make an RPG, posing it as a prequel to the game previously worked on – thus being the first in a series. Alongside it were the two other RPGs, which were later scrapped so all three teams could focus on completing Suikoden I. What's interesting is how much potential Konami saw, given it would cannibalise two projects to support Murayama's. I asked him about the other two. He recalled: "One of them was cancelled while it was still in the planning stage, so I don't remember the details. The other, I think, was an action RPG. I really don't remember much about that either."

If you've been keeping count, so far, there have been at least five cancelled games leading up to Suikoden I: a fighting game, a racing game, two other RPGs, plus, of course, Suikoden Zero itself (though not named, we'd guess the baseball game was Jikkyou Powerful Pro Yakyuu '95; it's uncertain what happened to the second racer from the five PlayStation projects). And as you can see from using the name Ted again, Suikoden borrowed aspects of Zero, despite being a prequel. The question, though, is why he didn't simply move the entire game over and finish it?

"The RPG we were planning for Konami's game machine was designed for the purposes of a portable game machine," explained Murayama, "and had a strong emphasis placed on the element of raising characters. More concretely, we had planned for many classes, and players were going to strengthen their characters through repeated class changes. But when we changed to developing an RPG on the PlayStation, since we were designing for a home console, we decided to place a greater emphasis on the game world and so we just decided to start over."

The primary RPG influences on Murayama are obvious, given their popularity in Japan at the time. I asked about this, and also clarification on a comment in the LEVEL interview, where it was implied he looked at the source code for Dragon Quest V. As he explained: "Back then, I played RPGs that existed at the time like Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy, but I never got their source code. Dragon Quest V was a particularly useful reference for me, and I studied the fighting balance and the data information as I played through it."

It's here, in the combat, where we get a glimpse of Murayama's genius, as he innovated on what were well-entrenched tropes by that point. Almost all RPGs allowed the player to run away from battles; this was standard. A few, such as Mother 2 / EarthBound (1994), had low-level enemies run away if you were sufficiently levelled, while in Suikoden, you could let low-level enemies go free. But Suikoden also introduced the option to bribe enemies, allowing players with excessive gold to buy their way out. But there were other innovations, too.

"In Suikoden, I was trying to focus on dramatically reducing the player's stress," revealed Murayama. "As an example, for the enemy encounter determination, it's set up so that if you continue in one direction for a certain amount of time, the chances of an enemy encounter go down. This is so that if you are heading for a certain destination, it will be less likely that you encounter an enemy, but if you are wandering around in order to level up, it will be easier for you to find an enemy. The idea behind 'Let Go' was so that you wouldn't have to fight enemies that would be easy to beat, and it works 100% of the time, or it's supposed to. 'Bribe' is an extension of this and is designed to let you choose to avoid battle while paying for it with a financial penalty."

The first game brought numerous innovations. In addition to the standard party battles described above, there were one-on-one character duels for major story scenes and also large army battles (these resembled Dragon Force, with hundreds of tiny soldiers, though mechanically were akin to janken). Another big innovation is that in addition to the main hero, there are 107 recruitable characters to be found throughout. As is well known, this is loosely based on The Water Margin, a Chinese novel over 500 years old. The story of which features 108 heroes or outlaws, who form an army, are pardoned and then face foreign invaders. Note the similarity between the traditional Chinese characters for the book (水滸傳) and the Japanese kanji for the game (水滸伝). We've given Wikipedia links if you want to read more, but honestly, it's not necessary. Localiser Harry Inaba explains: "It's a very popular story, so yes, I did know and read The Water Margin. However, I never considered The Water Margin during the game localisation process, and I personally don't think there's a legitimate connection between the two. I like Suikoden better, to be honest."

As it turns out, The Water Margin connection was a misunderstanding – it was simply a means of easily explaining the game concept to elderly executives. As detailed in the LEVEL interview, what Murayama had wanted was a large ensemble cast of supporting characters influenced by his favourite anime and manga. But he figured his bosses, in their 50s, wouldn't understand such examples, so he used something older, more literary, a metaphor which he felt they would understand: The Water Margin! Except they assumed it literally would be that, and Murayama chose not to correct them. I reiterated all this in my own interview, hoping for more details on how he originally envisioned the supporting cast.

"You are correct in saying that I was trying to create strong supporting roles," agreed Murayama, adding, "There are many Japanese comics in which the characters, other than the main hero, are attractive and become close friends. Some examples of that at the time were Captain Tsubasa, Saint Seiya, and Dragon Ball. In American comics, you might say that X-Men is something like that. I wanted to create a dramatic story with many characters like in those, so that during the game players could find the characters they liked – that was the starting point for the game. The reason this became 'Suikoden' is because when we did an in-house presentation for our game idea, the higher-class executives were able to grasp more easily what we were going for when we used the image of The Water Margin as an example of what we meant."

Revealed To The World

Early publicity included footage shown as part V-Jump magazine's V-Festival '94, with a subsequent VHS tape produced by Shueisha. Here's a direct link to the Suikoden section. The presentation was full of JRPG goodness since, in addition to Suikoden, it featured Dragon Quest VI, Chrono Trigger, and Breath of Fire II.

Capcom staff were obviously present, and Murayama has a fun anecdote about their reaction: "This is the event where Suikoden was first unveiled. I was sitting in the participants area and when the Suikoden announcement video showed there would be 108 characters, I remember there was a Capcom guy from the Breath of Fire II team sitting next to me, and he said something like, 'Are you seriously going to do that!?' <laughs> Also, since we were still in the middle of development, the one-on-one combat scene was different than the one that eventually made it into the finished version. The screen shown was a visualization that Ms Kawano hurriedly drew and put into the video."

When it came to Western coverage, a lot can be said. But it's important to grasp the zeitgeist of the times. Most magazines had already jumped aboard the Final Fantasy VII hype train, where seemingly every month, journalists would contrive some way of covering it – so other RPGs tended to be viewed as mere stopgaps. A lot of the PlayStation narrative in magazines was also guided by a more "laddish" pseudo-adult culture, where hints of sex and violence were enamoured, and there was less appreciation for nuance or beauty. Furthermore, Sony Computer Entertainment America had an officially mandated internal evaluation team which was opposed to 2D games – severely limiting the 2D releases compared to Japan and Europe. We're describing all of this so you can visualise the unreceptive environment Suikoden faced outside of Japan – and then be impressed when you see how it managed to overcome such challenges.

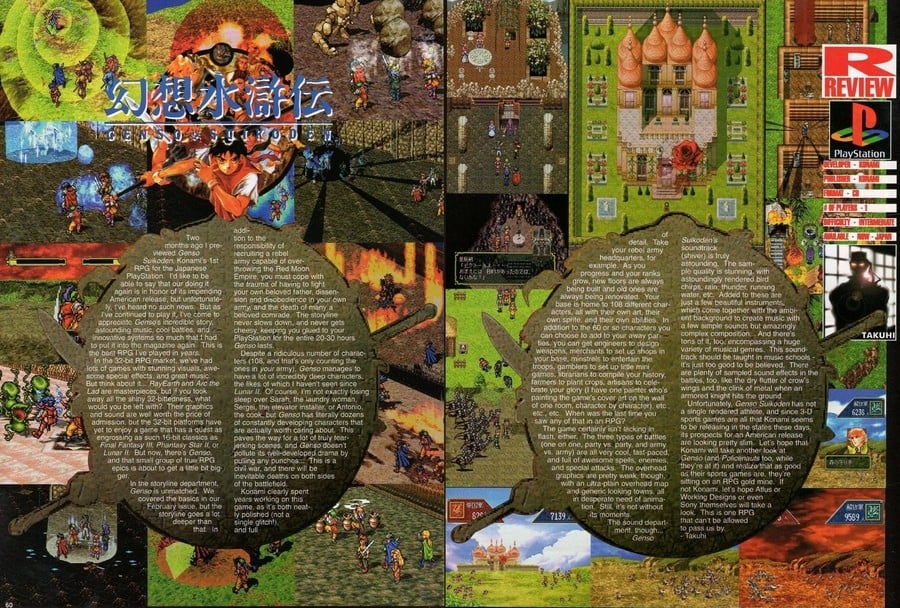

The earliest and best coverage was, of course, in Diehard GameFan, which reviewed it not once but twice! The first time was the Japanese release, in Volume 4 Issue 4, with Casey Loe as the main writer. That specific issue was this author's first introduction to Suikoden, and the words and screenshots provided by Loe made it a more exciting proposition than any other JRPG of the time, Final Fantasy VII included. The existence of those pages, like a laser through time, would result in the entire series being played, its creator being interviewed, and now these words you read here. At the time, Loe also stated, worryingly, that "prospects for an American release are looking pretty slim". The review crew scores were Loe 97, Dave Halverson 90, and Nick Des Barres 90. In a neat twist, years later both Loe and Des Barres would translate the sequel, alongside Metal Gear Solid localiser Jeremy Blaustein.

The second GameFan review was for the official US release, in Volume 4 Issue 12. The three staff scored it 90, 95, and 96, with Loe again acting as main writer. He spoke about how it took the genre in new directions and eclipsed all the other RPGs released that year. Electronic Gaming Monthly #90 scored it 8.5 / 9 / 9 / 8.5, winning the Editor's Choice silver award. The four reviewers referenced Final Fantasy VII and Dragon Force, but admitted it was – for the time being – the best RPG on the PlayStation. Other US mags scored it highly too. In the UK though, Suikoden struggled somewhat. Edge gave it a 7 in issue #41, shoehorning it into a one-sixth of a page review two paragraphs long ("unambitious", it said). Computer & Video Games, meanwhile, scored it 3/5, which is basically a 6. In fairness, they did praise Suikoden in the conclusion, but if you've read any UK magazines from this era, all of them, apart from Super Play, seemed to express shame when playing RPGs.

Regarding the English releases of Suikoden, localiser Harry Inaba had some great anecdotes. "At that time, I was working in the HQ office, mainly dealing with special tasks which didn't belong to other divisions," he begins, adding, "So Suikoden was given to me as a special task, and I organised a task force under my given authority. I don't remember how long it took since it was so long ago! It was officially a PlayStation title. I was transferred to Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, a subsidiary R&D company of Konami, after working on Suikoden, and interacted a lot with Murayama-san and the team on a daily basis."

Keep in mind the mid-1990s were still a wild west for localisations, and you were not always guaranteed quality. A lot of translations were downright awful, cheaply hashed together by staff who weren't native English speakers. Thankfully, Suikoden's translation was one of the best, for the time. So we asked, how difficult was the project? Did anything have to be changed or censored? "It was a pretty small team," admits Inaba. "At that time, game localisation was not handled in the way it is today. We didn't split the work between 10 translators and five editors or something like that. It was one translator who played the game from start to finish. And one editor who played the game from start to finish, and that was it. And our overseas counterpart checked the game before launch a couple of times and fixed errors. Like I said, we didn't have to rush the localisation process, so the translator, the editor and the final checkers could spend enough time to make sure the translation was good. I don't recall any major changes. Sony didn't have a strict censorship policy, at least at that time, and it was much, much easier to get content approval compared to getting approval from Nintendo of America."

We then pushed him on the topic of how important Suikoden was to Konami. Its inception was as a launch game for new hardware, before morphing into a flagship Konami title for Sony's new hardware, all while leaving a trail of cancelled games in its wake. Was there a lot riding on it? "I don't think so," says Inaba. "At that time, nobody knew PlayStation would be a success. But maybe it's just because I was staff. Maybe the higher management was pushing hard. The most interesting thing [about] Suikoden is it's actually the first game released by Konami on the PlayStation outside of Japan."

Inaba's memories of the PlayStation are mirrored by Murayama. In the LEVEL interview, he described being given total freedom to do what he wanted, since Konami's management wasn't certain PlayStation would succeed. This is speculation on our part, but based on various statements, it seems almost like Konami threw its weight behind PlayStation as a precautionary measure, mainly due to Square's switching allegiances away from Nintendo. This attitude was also reflected in magazines pre-launch; Ridge Racer may have been impressive, but journalists seemed convinced it would be another Nintendo versus Sega hardware generation.

As for Suikoden being the first Konami PlayStation game outside Japan – some sources claim NBA in the Zone predates it by a couple of weeks, but we couldn't verify this.

This concludes our first feature on the creation of the Suikoden series. Join us tomorrow when we'll be running the second part, which focuses on Suikoden II.

John Szczepaniak is a journalist and internationally published author. If you enjoyed all this interview material, please check out his Untold History series of books. There are over a million words of developer interviews across the series.