In our recent-ish feature on the Family Computer's 40th anniversary (hereafter Famicom), we mentioned Sega's SG-1000 console, which launched the same day. You may have seen some mentions on social media, but there wasn't a huge amount of fanfare online.

In Japan, 4gamer.net had a long interview with Masami Ishikawa of Sega's early R&D, Naoki Horii of M2, and Yosuke Okunari of present-day Sega. But in English, there was not much coverage, if any. Joseph Redon of the Japanese Game Preservation Society also lamented the fact Nintendo's system always overshadows Sega's. This is regrettable since, even though the Famicom outlived and outsold the SG-1000, it was still Sega's first entry into the home market and, therefore, an important step towards systems such as the Mega Drive, Saturn, and Dreamcast. Its legacy deserves examination.

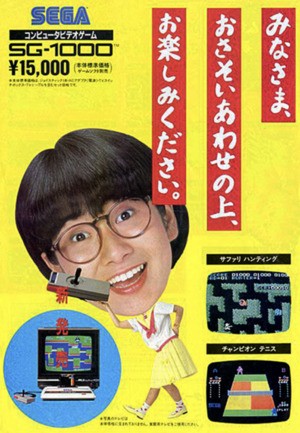

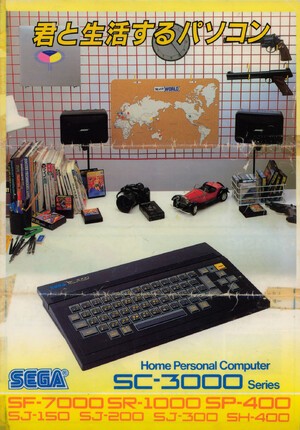

Part of the problem is Sega had a fragmentary approach to hardware. This leads some to conflate it with the later released Master System. Launched on 15 July 1983, the SG-1000 came out the same day as Sega's SC-3000 (basically the SG with a keyboard and extra RAM), while a year later, in July 1984, Sega released the SG-1000 II (we'll get into the minor differences later).

Also in 1983 was the Othello Multivision, an officially licensed clone of the SG-1000. Then there was a whole slew of add-ons and peripherals which go way beyond the scope of this article. A keyboard, the SK-1100, could turn the SG-1000 II into an SC-3000 equivalent. Then, roughly 15 months after the SG-1000 II, on 20 October 1985, the company launched the Sega Mark III, which would become the Master System outside of Japan (and within it – Sega would repackage the Mark III as the Master System in its homeland in October 1987).

The Mark III shell looked similar to its predecessor and was backwards compatible with SG games and the keyboard, while software for the original SG series and the newer Mark III model continued to be released concurrently. (South Korea and Taiwan also saw numerous MSX1 ports.) The final SG-1000 cartridge release, Loretta no Shouzou: Sherlock Holmes, actually had Mark III packaging! So you can see how, a little over two years after launch, the SG-1000 kind of gets lost in the fog of upgrades, reboots, conversions, clones, bootlegs, and add-ons.

To understand the SG-1000 properly, let's strip away a lot of confusion: we're keeping the SC-3000 coverage minimal while ignoring its SF-7000 floppy disk add-on and the licensed Othello Multivision; we're also ignoring the Korean / Taiwan scenes entirely. We're putting aside the smaller launches for the SG-1000 and SC-3000 in some PAL territories (Australia and New Zealand had thriving unique ecosystems); we're glancing past the peripherals, add-ons, and upgrades, and as much as possible focusing specifically on the default stock SG-1000 hardware from 1983. Importantly, we've also sought input from developers who worked on the games, clearly delineating between their SG-1000 and Mark III work.

As stated, there's not a lot of reliable SG-1000 coverage in English, especially developer interviews. There are some op-ed YouTube videos devoid of developer input and thus value; in August 2022, we ran a short feature; plus there's The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers trilogy, which speaks with many key Sega people. Another example is the Family Computer 1983-1994 book, which had a candid interview with Yuji Naka, where he described his first project at Sega.

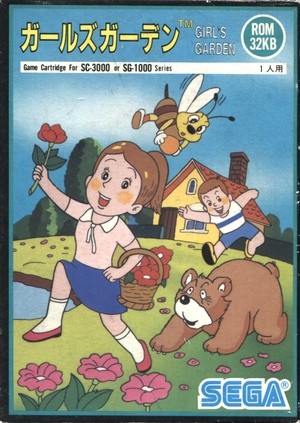

"It was a game called Girl's Garden," begins Naka, "One of my colleagues and I made it as part of our so-called rookie training. We were trying to find out the limits of the SG-1000. However, all of a sudden, our boss decided to put it on the market, so we had to finish it. The game was kind of cute, in which a girl named Papri had to pick flowers and bring them to this boy named Mint. I wanted girls to play it. I feel that a lot of things were considered thoroughly, and the concept itself is pretty organised, for being my first game. Though I say it myself, I think it was a pretty good game. We were also quite fortunate they turned our ideas into a product."

Naka isn't just being boastful; it's actually a wonderful little game, and would be included on Sega 3D Reprint Archives 3: Final Stage in 2016. Naka was then asked about his feelings on the success of Nintendo's Famicom, and which hardware had the better performance, when comparing it with the SG-1000 and SC-3000. He responded that at the time he thought, "Boy, I wish our games would sell more. Then I also told myself: man, you've got to do more!" After which Naka dropped the bombshell, "As for the performance, there is no doubt that SG-1000 and SC-3000 were better by far. It even had a Z80 chip for the CPU, the brain of the game machine. It was also easier to make games with it, since it had a lot of capacity. The Famicom and the game machines of Sega all had limitations, so I am quite sure all the developers had a hard time in that respect."

Anyone glancing around this page and seeing screenshots would be forgiven for thinking this hyperbolic statement was simply company loyalty – at the time of the book's interview, Naka was still a Sega employee, after all. When you think of the Famicom's most impressive titles, like Konami's Crisis Force or Sunsoft's Batman: Return of the Joker, and then look at Girl's Garden, how can Naka's claim be true?

To get the inside story, we contacted four SG-1000 developers, each a legend in their own way: Kotaro Hayashida, Youji Ishii, Satoshi Fujishima, and Takayuki Hirono. For a technical perspective, we also chatted extensively with Omar Cornut, developer of the Meka Emulator and director of the excellent 2017 remake of Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap. As we discovered, for a certain period anyway, there is a degree of truth to Naka's words.

But first, let's examine that 4gamer interview linked earlier, specifically the words of Masami Ishikawa, who joined Sega in 1978. The site asked Ishikawa if Sega expected home video games to become a big market. His response was that the head of R&D, Hideki Sato, should also be asked, then adding, "However, Sato-san and Kazuhiko Nishi of MSX had met, and there must have been talk of 'Do you want to join the MSX Group?' I believe there was a discussion about whether they [Sega] would join the MSX Group. When I moved from production engineering to development, my desk was next to Sato-san's, so I could often hear him talking on the phone. <laughs>"

This is another bombshell revelation since a lot of sources online try to angle the hardware as having been spun off from the ColecoVision. According to Omar Cornut, the "MSX1 and Coleco and SG-1000 are roughly same hardware", but the MSX connection makes the most logical sense.

In a Shmuplations translation of a Famitsu interview, Sato states the SC-3000 computer design came first and then, after hearing about Nintendo's Famicom, Sega decided to remove its keyboard and market the SG-1000 as a console alongside it (later selling a separate keyboard add-on). The SC-3000 specs are almost identical to the MSX1, with two differences being the sound configuration and the MSX1 having more RAM (8KB instead of 2KB). Even when the Sega hardware was the lead platform for a game, you'll often find a port to the MSX1. As an interesting side note, according to Cornut, "They're so similar that in Taiwan and Korea, a large number of MSX1 games were converted to the SG-1000 or Mark III, using RAM extension adapters or taking advantage of the Mark III RAM."

Why Sega chose to differentiate their home computer rather than join the MSX Group is unknown. Ishikawa's recollections, along with Sato's interview, paint a picture of a company tentatively wishing to enter the home computer market, almost becoming part of the MSX standard, before pivoting to challenge Nintendo and tackle both the console and computer markets simultaneously.

But the world of home systems in 1983 was getting crowded. In that same 4gamer interview, Yosuke Okunari describes seeing an article in a monthly manga aimed at children, which encapsulates the console war in Japan. "There was an article in CoroCoro Comic that said, 'From now on, game consoles are coming out! Among the Famicom, SG-1000, Pyuta Jr., and [Emerson] Arcadia, which one will you choose?' That's why I chose an Arcadia."

Of course, as history shows, Tomy's Pyuta and Emerson's Arcadia are now footnotes, while Sega and Nintendo's rivalry continued until the demise of the Dreamcast. We spoke with Kotaro Hayashida, formerly of Sega, who shared some deeply candid views on this. He joined Sega in 1983, having originally studied law, and would later go on to create Alex Kidd and a multitude of Mark III games. But before that, he was a designer for the following SG-1000 titles: Hustle Chumy, Champion Pro Wrestling, Zoom 909, Pitfall II, and Ninja Princess. With the 40th anniversary just past, we asked how he felt about it.

"The SG-1000 is a very nostalgic machine!" laughs Hayashida at first, but you can really feel the regret as he goes on. "It was 40 years ago, but I have nothing but frustrating memories. That's because there was Nintendo's machine, after all. Unfortunately, compared to Nintendo's Famicom, the SG-1000 had a very low commercial advantage as a hardware product. A particularly significant difference is the number of colours that can be produced – which visually had a huge impact on the consumer. This difference was reflected in the number of units sold. Myself and other game developers tried to make up for the hardware performance gap, but unfortunately, we could not catch up with the Famicom."

In the third volume of The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, Hayashida shared further details. "Nintendo's hardware allowed for four-colour sprites. At Sega, our SG-1000 sprites could only be a single colour. Nintendo used a custom chip to make this happen. These extra colours gave the graphics a lot of impact, and really helped sell the system. The rumour I heard was that Hiroshi Yamauchi ordered three million of those customised chips in order to get a discount from the manufacturer so that Nintendo could sell the Famicom for under ¥15,000. Sega's hardware initially utilised a generic chip, not a custom one. This made programming easy – but left Sega with no way to distinguish their hardware. Sega simply didn't have the colour capabilities to compete. If you want my personal opinion... Not as a Sega employee, that is, but as a designer, I would have preferred creating games for Nintendo back then. <laughs> But I was hired by Sega, and wanted to make the best games possible for them, for their hardware. And I did."

Looking over Hayashida's portfolio, he's not wrong – Hustle Chumy was an original title with a fresh take on single-screen collect-a-thons, while Pitfall II features his original redesigned maps and makes great use of the limited colour palette (Minoru Kidooka was his programmer). Meanwhile, his later Sega games are regarded as timeless classics.

Hayashida's regret about the colour capabilities is a core part of the debate of SG-1000 versus Famicom, and it's important to frame this discussion chronologically based on the order, volume, and quality of games released. The SG-1000 launched with seven strong games, versus Famicom's paltry three – but let's give Nintendo some charity by allowing its entire 1983 catalogue, which was still only nine games. The SG-1000, meanwhile, had considerably more games released in 1983; some sources show 15, others 21 games, in both cases more if you count Othello Multivision titles. Of all these, around seven featured screen-scrolling (Space Slalom is debatable). There were also several more scrolling games the following year.

This is why historical context is so important. In his long-running Video Works series, game journalist and Limited Run Games media curator Jeremy Parish claims the Famicom's hardware scrolling capabilities put it ahead of the SG-1000. His statement isn't quite accurate, though. For the first 12 months on sale, not one Famicom game featured any scrolling of any kind – pause for a moment and consider that. The first examples were Hogan's Alley in June 1984, but that was simply between levels, and not player-controlled. The first player-controlled example was Lode Runner in July 1984, allowing free horizontal movement. So for the first 12 months, Sega actually had the advantage, with several of its launch line-up games and subsequent releases all featuring scrolling, meaning the SG-1000 did in fact outperform the Famicom – if not in colours, then in movement. This makes Yuji Naka's earlier statement true, at least for a time.

Naka himself also mentioned scrolling in his aforementioned interview: "I studied the technology of programming by trying new things, and by analysing what others had created. Programmers would compete within those limitations, and it was an era when technologies would advance every year. You can't get a real good kick out of the hardware nowadays, since it's capable of doing anything. That was the time when even making the scrolling of the screen a little faster was an amazing thing."

Cornut offers some context to this. "I'm not sure how meaningful it is to compare the scrolling of the launch games," he says. "Eventually, it's clear the Famicom had a hardware advantage. The SG-1000's CPU was better, but ultimately its graphics chip wasn't. It's also true the SG-1000 was never pushed far, the same way MSX1 titles were; I mean, some MSX1 titles really pushed the hardware. Whereas Sega switched their efforts to the Mark III fairly fast."

This is true; once developers got the hang of the Famicom architecture and better chips were available, the quality of the scrolling blew away what the stock SG was capable of. Also, by the time the Famicom's scrolling capabilities had become impressive – thanks to increasingly advanced chips included in the cartridges – it was late 1985, and Sega had already abandoned the SG-1000 in favour of the Mark III. (Fun fact: Super Mario Bros. came out a mere 37 days before the Mark III.)

The later released Famicom games benefited from improved mapper chips, and while it's an overly reductive statement, try to imagine newer mapper chips being almost akin to enhancement chips like the Super FX – they all expanded what was possible on the hardware. The Famicom did eventually outperform the SG-1000, but it took a while for both programming knowledge and expanded cartridges to make this possible.

After Hayashida, we contacted his friend and former Sega colleague, Youji Ishii. Joining Sega in 1978, at a time when the company dealt more with "mechatronics" than videogames, he would ultimately go on to create Fantasy Zone and be producer on Out Run, Golden Axe, Panzer Dragoon (and PD Saga), NiGHTS, Guardian Heroes, Sonic Adventure, and Lost Odyssey, to name only a few.

But before all that, he was the planner on SG-1000 titles Sega Flipper, Golgo 13, and Champion Boxing. Mentioning the anniversary, we asked his recollections, to which he replied: "15th July was the 40th anniversary of the SG-1000, and forty years ago, I was very happy to be involved in the production of Sega's SG-1000 games. Today, I am the CEO of Arzest, a game production company. My COO is Naoto Ohshima, creator of Sonic the Hedgehog, and currently, Arzest is producing Sonic Superstars for Sega, which I hope everyone is looking forward to. The reason I'm still making games like this today is because of the big influence of the SG-1000."

Ishii then added, "My fondest memory of SG-1000 game development is Champion Boxing. I was the game's designer; Yu Suzuki, who had just joined the company, was the programmer; and Rieko Kodama was the artist. Many of the early SG-1000 titles were ports of arcade games. Among them, however, this Champion Boxing was an original new title. Every day, the three of us chatted about how to proceed with the game's development. Looking back, this is a very happy memory." These warm recollections also show how two other legendary figures, Suzuki and Kodama, started their careers with the SG-1000. Champion Boxing would later be converted for use in arcades, using SG-1000 hardware.

While Sega published all of the SG-1000 branded games and developed most of them, Compile was also involved heavily. We contacted Compile programmer Satoshi Fujishima, creator of the Golvellius series and Zeroigar on PC-FX. His early career, however, included SG-1000 games, including the tour-de-force that is Gulkave. He's credited with programming, game design, and music.

Given how Gulkave pushed the SG-1000 hardware, we hoped for some exciting revelations. Fujishima replied, "I was involved in the following early SG-1000 titles, Borderline, N-Sub, and Safari Hunting; I just did some of the planning and pixel art. The only SG-1000 game where I was in charge of programming was Gulkave. Safari Hunting was programmed by Takayuki Hirono, often credited as Jemini, famous for his work on Zanac; I created the animal pixel art and other planning aspects. The Borderline and N-Sub programmes were created by Masamitsu Niitani, former president of Compile."

Fujishima then apologised for the brevity of his answer, explaining he was in the middle of a very busy project. It's not the wild anecdotes we hoped for, but it did provide staff names for games previously uncredited and reminded us we had Hirono's email. Probably best known for creating the Zanac / Aleste series of shooters, plus Gunhed on PC Engine, Hirono also worked on Safari Hunting, C-so!, Choplifter, and Gulkave for the SG-1000. Looking over his portfolio, he is, by all accounts, a genius programmer. So, we pushed for technical details on the SG-1000, specifically in relation to Yuji Naka's statements about it being more powerful than the Famicom.

"The SG-1000 is a piece of hardware which has gone up and down in my estimation over time," reveals Hirono. "It uses a 9918 video chip, which I had almost no chance to touch on home computers, so in the early days, I had the impression it was somewhat unusual hardware. It's not that it's bad; I'll say the problem is that I didn't really know how to handle or use it. And apart from the video system, the available RAM memory was low. This starts to have a negative impact. For example, in the game C-so!, some information leaks into the video memory. The MSX1 has a similar configuration, but that one is a little slower to run, probably due to its emphasis on versatility. In fact, Gulkave is less prone to processor lag or slowdown on the SG."

This talk of available RAM leads to an interesting error in Sega's licensed books and the possibilities of upgraded games. According to page 28 of the official Sega Consumer History book, the SG-1000 from 1983 came with 1KB of RAM and 2KB of Video RAM. The SG-1000 II update, released a year later, is stated on page 32 to have the same VRAM but double the previous RAM, with both now being 2KB. Cornut, however, points out, "It's a mistake in the book. The SG-1000 has 1KB of RAM and 16KB of VRAM. The Mark III also has 16KB of VRAM, but can access it faster. SC-3000 has more RAM, and so does the Mark III / SMS. Some units of SG-1000 II have a 2KB RAM chip, but it's connected in such a way where only 1KB is accessible. It also has 16KB of VRAM. I've also just looked at Pitfall II in a debugger. It came out after the revamp, and it uses 1KB – no game needs more than 1KB of RAM, an exception being Q*Bert for the Othello Multivision, which doesn't work in an SG-1000. Games like The Castle and Loretta no Shouzou have increased RAM and ROM, and both work on the SG-1000 since they're just cartridge upgrades."

The two games Cornut mentions, The Castle and Loretta no Shouzou, are important because they represent rare examples where the capabilities of the SG-1000 hardware were expanded through enhanced cartridges, much like the Famicom enjoyed. The Castle includes an additional 8KB of on-board RAM, while Loretta's ROM is four times the size of your standard release. Both of these, of course, came out after the Mark III, showing Sega preferred to enhance the base hardware rather than cartridges. When you consider the possibilities of enhanced cartridges and the fact programmers were barely accustomed to the architecture before Sega abandoned it, one gets the feeling the SG-1000 didn't reach its potential.

We conveyed these thoughts to Hirono, who astutely pointed out similar hardware which did reach higher levels. "Considering the various games that later came out on the MSX1, which also used the 9918 video chip, history might have been different if more effort had been put into the SG in the early stages and it had held its ground. I've been thinking that recently – such an outcome might have been possible. At the time of release, the SG-1000 would have had a slight advantage over the Famicom in the power struggle for home consoles. Sega was also better-known, thanks to its arcade games. However, the market's attitude was turned upside down when word got out that 'Namco had entered the market'."

Namco games appeared on both systems; Galaxian hit the Famicom in September 1984, Namco being one of the system's earliest third parties alongside Hudson, while Galaga hit the SG-1000 in November. It's around this late Q3 period when things shifted. By the end of 1984, whatever head-start Sega had quickly slipped away as further third parties signed up to Nintendo and programmers improved. Jaleco's Exerion came out in 1983 on SG-1000 (some places say early 1984), and nothing on the Famicom at that time equalled it. But by February 1985, Jaleco was a licensed third-party with Nintendo, and Exerion was duly ported, with full background scrolling and a better colour palette. The big hypothetical then is, how different might things have been if Sega had stuck with the original hardware and pushed it further? Cornut, who has a better understanding of the hardware than most, makes some excellent points.

"MSX1 hardware is very close to SG-1000, and if you look at late MSX1 titles like Nemesis, which pushed the hardware nicely, you'll see they're quite ahead of anything done on the SG. Mostly because people were more experienced and carts used more memory – technically, it's possible to do the same on the SG. It's just at that point, there were few devs focused on it. Loretta is mostly static screens, not a big wow factor, but it takes advantage of that larger cart ROM. The biggest issue was that programmers initially weren't experienced with the hardware, and by the time they were experienced, they had moved on to other systems. But you can see a clear progression in game quality from 1983 to 1985, and that progression is mostly due to developers being better at programming the Z80, and better at dealing with the TMS9918 video chip. But ultimately, devs had moved on. Perhaps if the SG-1000 launch was more successful, followed by more and better games all through 1984, it would have tilted things a little more in Sega's favour, and then people would have pushed it for longer, and we'd have seen fancier titles in 1986."

If you want to see just one example of what could have ended up on the SG-1000, Cornut links us to a page on Dynamite Go Go for the MSX1. It's a recently made retro game that pulls all sorts of tricks, but given that it runs on MSX1 hardware, Cornut assures us it could have run on the SG-1000 with a RAM expansion similar to what The Castle used.

A lot of what's been said has, much like the system itself, been overshadowed by discussion about the Famicom. About what could or should have been. But what was it actually like to play? To have been alive in the mid-1980s and experienced this hardware as one's sole access to home gaming? For its brief period of activity, what did it offer? The below list of 10 isn't necessarily the "best" games, but each is interesting for different reasons.

10 Interesting SG-1000 Games

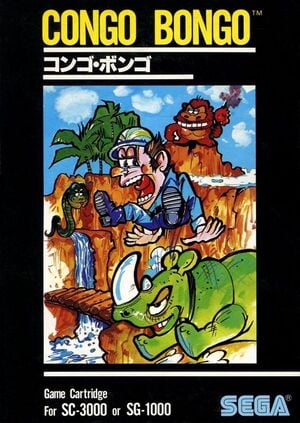

Congo Bongo (1983)

Not the obvious choice for an SG list; rather than a straight port of the arcade original it's more like a "reimagining", losing the isometric perspective and only having two levels (weirdly, the cover still shows the rhino, despite this level being cut). But as a launch title, it's interesting, especially compared to Donkey Kong on Famicom.

Both Sega and Nintendo's 8-bit systems launched the same day with a single-screen man-versus-ape game, where the goal is to reach the ape. Each was converted from arcades; both arcade originals were programmed by Ikegami Tsushinki.

Look at the opening level in Congo Bongo, the bright pastel colours, the tropical landscape, how warm and inviting it is. Now imagine seeing Donkey Kong's bland industrial opening level at the same time - if you were a 7-year-old Japanese child in 1983, which system would you want your parents to bring home?

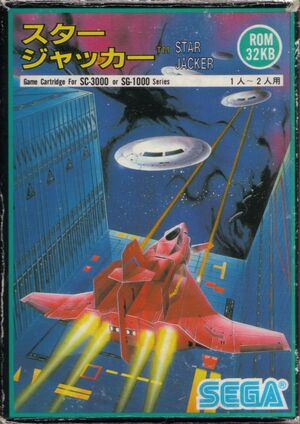

Star Jacker (1983)

An impressive launch title - fast scrolling, lots of sprites on-screen, and there's even some pseudo-scaling!

If you've not heard of it before, Star Jacker was an early Sega arcade title, with the only home conversion being for the SG-1000. It's also unlike any other 2D shmup of the era: you start with four ships all visible at once (three in the arcade original), all controlled at the same time. If one gets hit, it's destroyed, and you have one less life.

Since they fire simultaneously, you start off with a strong offence, though it's difficult to manoeuvre between enemy fire. When down to your last ship it's easier to fly, but you have less firepower. This sliding ratio of attack versus survival is exquisite.

Over 40 years later it still feels fresh - it's sort of a basic prototype for MBG's Shoot 1UP. The question is, why did it take so long for someone to reuse the concept?

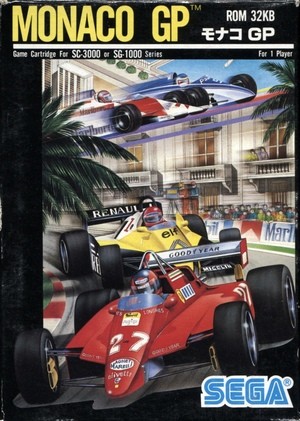

Monaco GP (1983)

Another Sega arcade port, and this one is special for several reasons.

The 1979 original used discrete circuits rather than a CPU, so it cannot be emulated – in fact, until the Sega Ages Memorial Selection Vol. 2 on Saturn, this SG port was the only way to experience it.

Gameplay is your standard racing up the screen, avoiding other cars (and the occasional ambulance) for a high score. It's a bit similar to Konami's Road Fighter, which would come out in 1984.

Things which set Monaco GP apart are sections of icy roads, driving in the dark (other cars can only be seen in the cone of your lights), and the ability to jump in the air right over other drivers (your car even does a little spin).

It's also blindingly fast, maybe a little too fast at max speed. Higher speeds equal higher scores. Nicely showcases the scrolling capabilities of the stock hardware.

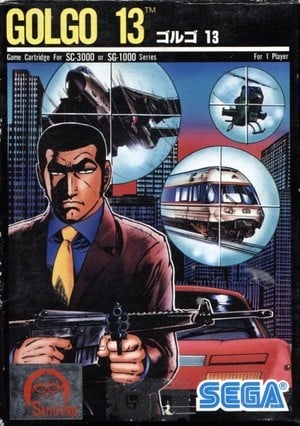

Golgo 13 (1984)

We almost put Ninja Princess in, but its more advanced remake on Mark III dissuaded that plan (localised as The Ninja).

In fact, there were quite a few excellent games with upgraded ports on later hardware, such as Flicky and Doki Doki Penguin Land, which left us hesitant to list them. Golgo 13 made it because, while just a simple score-attack shooter akin to Space Invaders, it's an original title, a system exclusive, and one of several licensed properties on the SG-1000, showing that Sega was trying hard to court consumers.

You control Duke Togo in a red sports car, brandishing a rifle, shooting out windows on a speeding train to free passengers. The catch is you need to shoot through oncoming traffic and a freight train while avoiding a helicopter's shots (you can also shoot these down).

Hitting the freight train will ricochet the bullets back at you. The sky changes colour after round 10.

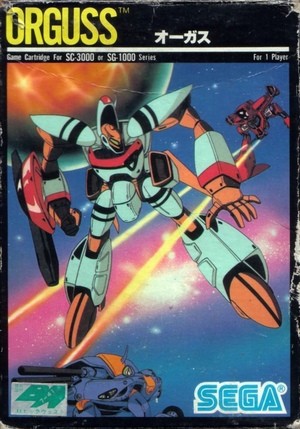

Orguss (1984)

An early hori-shmup where you can transform between a vertically oriented mecha and a horizontally oriented ship.

The robot has greater mobility and rapid shots, but is slower, while the ship is fast but less responsive. Swapping forms is essential since you have a time limit to complete the mission – once done it loops to the start.

Based on the anime Super Dimension Century Orguss from 1983, it plays a lot like the Famicom release of Super Dimension Fortress Macross, which came out in December 1985. Both are anime licenses from the same universe, both with transformable ships that control similarly, and both are single missions which loop round.

The difference is the Famicom only received its equivalent 18 months later. Orguss was released May 1984 and represents the last fleeting moment of SG superiority over the Famicom, which would finally see screen scrolling with Hogan's Alley in June, and Lode Runner in July.

Girl's Garden (1985)

A system exclusive and Yuji Naka's first-ever project, this obviously had to make the list. (Hiroshi Kawaguchi was co-programmer and did the graphics, later becoming an important composer for Sega.)

Its ultra-cute exterior hides a genuinely excellent game with inventive mechanics. You control Papri and need to collect ten flowers to give to a boy named Mint. The screen scrolls horizontally, looping back on itself, and flowers will randomly sprout and grow around the playfield.

Picking one too early gives you nothing, while picking old flowers will reduce those already collected. There are also bears roaming the garden and environmental hazards (bodies of water), leading to a tense scenario of grabbing flowers at the precise moment and avoiding danger all while a timer ticks down.

Bears can be distracted with honey and bees drop items for bonus points. There's also a minigame where a giant version of Papri jumps over oncoming bears.

Pitfall II: The Lost Caverns (1985)

Admittedly, being a MyCard release, this requires the Card Capture adapter peripheral to run on stock hardware. But even so, it's a fine third reworking of the Atari 2600 and Sega arcade games. Which you prefer will be a matter of personal taste.

The Atari original is well documented and was remade by Sega for arcades, with improved graphics, new mechanics (minecarts!), completely different layout, and a challenging lives system. Sega then remade it again for the SG-1000, altering the map and graphics to suit the hardware.

A lot of people say this is just a port of Sega's 1984 arcade remake, and while the SG release does contain certain identical sections, it would be more accurate to describe it as an all-new remix – a remake of a remake.

Comparing the maps of the Atari 2600 original, the Sega arcade release, and this home version, reveals three similar but distinct games. (Here's an exhaustive comparison of them all.)

Gulkave (1986)

A glorious showcase for what skilled programmers could do with the hardware, featuring not just scrolling but multi-layered parallax scrolling! The music is fairly decent, too.

It also came out on the MSX1, though, as explained by Takayuki Hirono, this version is the best. Everything about Gulkave screams more, from the multiple layers of background, to your ship's energy bar allowing multiple hits, to the weapons bar along the bottom.

There are nine different weapons available, accessed by collecting numerical icons which cumulatively select the next weapon before looping round. Technically, the Famicom port of B-Wings had more weapons (twelve, including your weaponless peashooter), but let's not quibble.

While Nemesis represents a technical peak for the near-identical MSX1 hardware, we're inclined to say this impresses us more. Beyond the notable technical achievements, it's a lot of fun and, thanks to a generous continue system, not too difficult.

The Castle (1986)

A multi-screen collect-a-thon similar to Jet Set Willy and countless others, with some tough puzzles thrown in and 100 rooms to explore.

The ability to collect colour keys in one room and use them in any same-coloured door in another room might lead some to describe it as a proto-Metroid, if they were trying to be cute.

Released across multiple computer systems, and seeing a sequel that was ported to the NES, the gameplay here is solid and fun but nothing overly unusual.

What makes The Castle special is that the SG-1000 cartridge came with an additional 8KB of RAM built-in, thus adding eight times the amount of regular memory that came with the console.

Released late in the system's life, it showed how clever developers could push the hardware. Make sure to grab the map in the upper right of the first room.

Loretta no Shouzou: Sherlock Holmes (1987)

Let's be honest, no one reading this will ever play this game. It's a slow and sprawling graphic adventure based on Sherlock Holmes, with a lot of Japanese text to read. Even if it was fan-translated, its allure will be mostly academic.

This makes the list because, at 128KB, it's four times larger than your standard SG-1000 game, the largest ever released, and it's also the final cartridge release for the SG.

Not that you'd know, given it came in Mark III-styled packaging; even the official Sega Consumer History book lists it with other Mark III games, briefly mentioning it's SG compatible.

Make no mistake, you can pop this cart into your stock 1983 unit, and it plays. A high watermark for how the original hardware could be pushed, alongside titles like Gulkave and The Castle, hinting at the possibilities if history had played out a little differently.

Special thanks to Omar Cornut, who spent a lot of time answering our technical questions and doing fresh research for this article. Thanks also to Joseph Redon, who assisted with Japanese interview translations.

John Szczepaniak is an internationally published man of mystery; his latest book, The Untold History of Game Developers Volume 5, is on sale now. All proceeds go to funding his menagerie of blunderbusses and bottled trilbies.