A legendary creative force in the games industry, Peter Molyneux has been involved with some of the most innovative video games of all time. He effectively birthed the 'God sim' genre with his 1989 release Populous, turned players into business owners with Theme Park and spearheaded the design of groundbreaking titles like Dungeon Keeper, Fable and Black & White.

All of those games were created either at Bullfrog – the company he founded with Les Edgar in 1987 – or Lionhead, the studio he established in 1997 following EA's purchase of Bullfrog a few years earlier. In 2012, Molyneux embarked on another chapter in his eventful working life – and it would begin with one of the most controversial projects of his entire career.

"[At] Lionhead, the thought was to keep the company small and get passionate people together," Molyneux tells award-winning writer and Time Extension contributor Simon Parkin on the excellent My Perfect Console podcast. "But there's this irresistible urge to grow a company; it seemed like, in the blink of an eye, it went from 25 amazing, incredible people to over 350." He had also taken on a senior role at Microsoft's European game division, which required a constant stream of meetings and regular flights from the UK to Microsoft's HQ in Redmond, North America. The end result was that Molyneux found himself becoming increasingly distant from the one thing he loved doing the most. "I lost contact with designing," he laments.

Molyneux realised that history was repeating; the same thing had happened when EA gobbled up Bullfrog, and he realised that drastic action needed to be taken in order to break out of the pattern. "I wake up, and I realize it's not what I want," he says. "I decided to hand my notice in. I left on the Monday morning and started 22cans in the afternoon."

22cans would not be another Bullfrog or Lionhead, Molyneux decided. He ruled that the studio would never have more than 25 staff at any one time, thereby avoiding the temptation to expand it into something uncontrollable or unwieldy, as had happened at his two previous studios. It was a noble aim, but even Molyneux couldn't have predicted the storm of publicity that 22cans' debut title would cause.

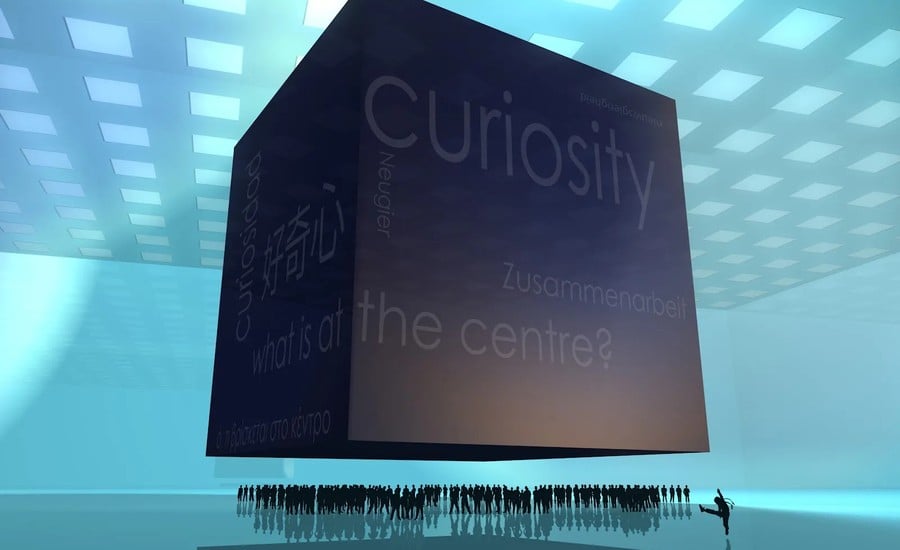

Speaking to Parkin, Molyneux makes a point of regularly referring to the game – initially called Curiosity but later changed to Curiosity: What's Inside The Cube? to avoid confusion with the 2011 Mars rover of the same name – as an "experiment". This was truly uncharted territory, and it would be inspired by the growing ubiquity of the modern smartphone.

"When we started off 22cans, I didn't have a game in mind," he admits. "[But] I was just sold completely by Steve Jobs standing on stage with the iPhone. "And the one overarching thought in my mind was, everyone in the world is going to have a gaming console in their pocket – but all those people in the world, they've never played a computer game before in their lives. So, what is the minimum motivation that we can give to someone that has got access to games the whole time?"

Molyneux knew this would be a very different proposition from what he had designed before. His previous titles had required players to focus and be immersed in the game world, but this wouldn't necessarily be the case with a smartphone game. "[Those games] required a story and a narrative, and you couldn't just dip in and out. But the realization is you've got a phone in your pocket; you could be sitting on the bus, and you could whip the phone out and do something and put it back. That required a complete mindset change in thinking."

Instead of allowing the player to become a god, run a theme park or save a fantasy realm, Molyneux's first smartphone game would abandon the concept of a story altogether. "What makes sense is to do these experiments – and the first experiment we'll do is about motivation," he continues. "What is the minimum thing I can say to a player to motivate them to do the most banal thing? Well, the minimum was that I say there's something wonderful inside. And this is Peter Molyneux talking, so I'm probably going to use 'amazing, life-changing' and 'world-shattering', because that's the dialogue. Unfortunately, that decides to come out of my mouth when I talk to the press."

In case you weren't aware, Curiosity: What's Inside The Cube? involved thousands of players tapping away at a giant cube to uncover what was in the middle. "There was this floating cube constructed in millions of tiny blocks, and players around the world would chip away at them," explains Molyneux. "The idea was that whoever chipped away the final block would reveal what was at the centre of the cube and win a life-changing prize."

As simple as the concept may seem, the launch of Curiosity: What's Inside The Cube? didn't go according to plan. 22cans submitted it to Apple on September 28th, 2012 for approval to be published on the iOS App Store, with the view to hit a proposed release date of November 7th as a free download. However, unbeknownst to 22cans, Apple pushed the game live a day early – the same day the Android version went live. As a result, many people were unable to connect to the game's servers and negative reviews ensued. When 22cans overcame these teething launch problems, it was soon apparent that it had underestimated user interest in the whole project by quite a wide margin.

"Within an hour, there were 200,000 people tapping away at the cube," Molyneux tells Parkin. "I honestly thought there would be about two-to-five thousand in total over the whole experience. No one realised this, so we had to increase. We increased the size of the cube massively so that it would take longer. [If we hadn't], it was all going to be over [in an] afternoon."

Pretty soon, the game wasn't just about tapping to get to the middle of the cube – emergent behaviour became noticeable among the player base. "This magical thing happened," says Molyneux. "We didn't plan, we didn't design, we didn't think about this – but people [began to] work together to tap these pictures out on the side of the cube. We had initially we had lots of penis pictures. Then we had a group of Italians that every day would come on and change all the penises to palm trees. We had seven proposals of marriage. We had the complete retelling of 9-11. People would be tapping away, and they'd cut without any other form of communication at all. They would create these communal pictures."

According to 22cans, 27,798,516,200 cublets were tapped at an average rate of about 1593 cublets per second during the lifespan of the game. Despite increasing the size of the cube considerably to prolong the experience, the experiment came to a conclusion on May 26th, 2013 – and the life-changing prize was finally revealed. "Eventually, the centre of the cube was reached and [it was] someone in Scotland [who won]," says Molyneux. "Unfortunately, it was virtually the first tap that he had done on the cube! We announced that he would be getting a share of the profits from the next game that we were going to release."

That winner was Bryan Henderson from Edinburgh, and while the prize would indeed involve a share of future revenue, he was also informed that he would be immortalised as the supreme being in 22cans' next game, Godus – a spiritual successor of sorts to Populous, the game that kickstarted Molyneux's career back in the late '80s. While on paper, this did indeed seem like a genuinely life-changing prize, the reality was a little less cheerful.

Henderson told Eurogamer in 2016 that he had had little to no contact with 22cans regarding his prize, an "inexcusable" situation which Molyneux would put down to the fact that the point of contact at the studio that was supposed to keep Henderson in the loop had left, and no replacement had been assigned. It was also revealed that Henderson was unlikely to receive any monetary reward and that his reign as the ultimate god might only last for six months. The life-changing prize ended up being something of a disappointment, and the negative press triggered by this has arguably overshadowed Molyneux's career ever since.

"It was my fault," admits Molyneux when discussing the fallout from the competition with Parkin. "I still stand by the innovation of the experiment – it was just the final prize. I had three more experiments planned, but the controversy of the first one meant that I couldn't do any more. I had thought of doing Curiosity again; I'm asking myself, what is the minimum prize that we can say? 'There's a box of Quality Street in the middle of the cube, and someone's going to win it.' Would you still tap? And I think people probably would. I don't think it was about the prize; it was all about the journey to the prize."

He's also keen to stress that, despite the sheer volume of people playing, Curiosity: What's Inside The Cube? didn't actually make 22cans any revenue. If it had, then the prize would clearly have been more appealing. "We didn't make any money out of Curiosity. I think you could today, with the advert revenue that you get in... you [could] give a substantial cash prize. But then I think it would probably be categorized as gambling."

Still, it wasn't entirely negative, and Molyneux reports that there was a rather unexpected benefit for some players. "We did have an enormous number of people say, 'I use Curiosity to get sleep at night.' They just found the sound effects and the visuals just incredibly relaxing. I think a lot of the time, with mobile gaming, relaxation or escape is what people want. They don't necessarily want drama and excitement – they want a way to escape."

[source shows.acast.com]

Comments 2

Honestly, it was a pretty interesting if very of our times idea, but it was the ultimate prize at the end that fell short. If something truly cool had been inside, and it had actually played out properly as planned, it would have totally fulfilled its promise and potential. Credit where it's due for coming up with one of these ideas that just becomes its own snowball effect though. People dream of coming up with one of those kinds of lightning in a bottle ideas all the time and never hit one, but Peter and his team totally nailed it. Can't deny him that at least.

I just love the fact the winner's "life changing" prize turned out to be being ignored for two years, then given a poster!

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...