You've likely been following the debacle and fallout from recent Pac-Man World events, where staff were not credited and it required fan campaigning to right the injustice. Sadly, such injustices have been happening in Japan for more than 40 years. When I spent three months in Japan researching my trilogy of books, The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, and interviewing over 80 game developers, several common themes cropped up:

- They had little, if any, awareness their games were even known outside of Japan, let alone popular.

- They were utterly shocked that this Englishman and his French photographer (Nico Datiche) were travelling around the country interviewing them.

- Japanese companies hated crediting staff and would aggressively forbid it - even going so far as to get another programmer to remove credits before release!

Of all the questions I asked (first game seen, office layouts, etc.), game crediting and nicknames were always on my list. Proper crediting for work is close to my heart; indeed, it's something I've always fought for – and even been punished for. When I was a freelancer for the now-defunct GamesTM magazine, writers were always credited for their features. Then, when another editor took over, there was a change in policy and a shift to be more like EDGE magazine – which, at that time, didn't credit its writers on the pieces they had written. I didn't like this change, so decided to sneak my name into articles – like Warren Robinett did when creating Adventure for the Atari 2600 – resulting in a lifetime freelancing ban for my efforts.

Anyway, Japanese game developers have suffered the same hardships since the inception of video games. Many of the game developers I spoke with in Japan – from the famous like Naoto Ohshima to largely unknown individuals – had examples of credit denial, either regarding themselves or a colleague. The persistent and fanciful urban myth that in Japan you have a job for life is not true – as will be shown, Japanese creators were insidiously denied credit by their companies out of fear they would go and work for rivals.

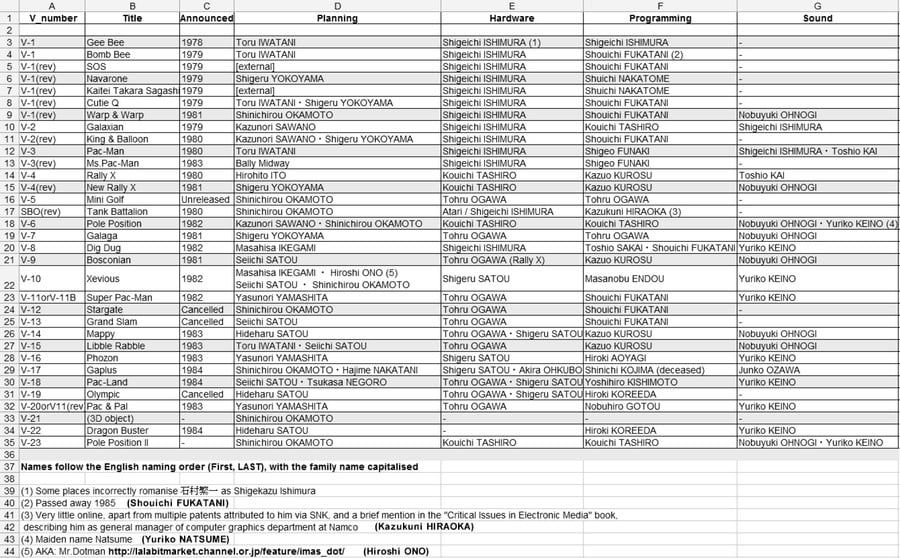

What follows is a curated selection of quotes from my journey. Their name, so they won't be forgotten, the work they are famous for, and their sacred words. The first quote is Professor Yoshihiro Kishimoto, formerly of Namco, who was so saddened by the practice that he provided me with a list of Namco staff and the games they worked on, imploring that it be shared so the world would know. Kind of ironic, given recent Pac-Man World events. Please spread this Namco staff list:

Professor Yoshihiro Kishimoto (Pac-Land, Famista)

My family name is Kishimoto, so my nickname was "Kishy", or Kissy. As for the reason why we used nicknames, at that time there was no such thing as the end credits for staff. For example, there were end credits for movies, for staff, but not for games. The names of people on development teams were kept secret by the company so they wouldn't be lured away by competitors. That's why they used nicknames.

When I joined the company, which was in 1982, my supervisor told me it was kept a secret, a company secret, as to who was working on or who created which games. Because if that was known, then rival companies would come and headhunt you and take you away from your company if they discovered that you made fun or interesting games.

In Japan, there are many things that I cannot say in public. This is one of the reasons for my agreeing to your interview. For instance, if I were to mention the names of the people that I did planning with, like Hyodoh, or Shinichiro Okamoto, this would not be accepted or approved by Namco for publication in Japan. They would say it's no good, you have to take that out. So I want to document it for the record, for future generations.

Naoto Ohshima (Sonic the Hedgehog)

I was credited as Rocky Nao in some games. Sega forbade us from using our real names in credits at the time. You know, I didn't put a ton of thought into my nickname, but I believe I had just seen the Rocky movie…. <laughs> It was probably to prevent headhunting and also for copyright reasons. Having real names provides evidence of what each person contributed to the game.

So, for example, that opens up the possibility that staff members could claim ownership over their work and sue for a percentage of the game's revenue. Such a lawsuit probably wouldn't fly under Japanese law, but in another country, who knows? Nowadays, companies deal with this issue by making new employees sign an agreement that anything they create while employed at the company belongs to the company. But there was nothing like that in those days.

Kouichi Yotsui (Strider, The Karate Tournament)

At the time, Capcom forbade employees from using their real names in the credits so that they couldn't be lured away by headhunters. Most employees from Capcom just chose whatever name they liked. That's the reason I use the name Isuke. I'd worked on a number of games that didn't get out of the development stage, so when I finally finished a game, I wanted to commemorate it by using the first character of Japan's hiragana syllabary in Iroha order. So that's the "I" part, and then "-suke" is simply a common suffix for Japanese male names.

Michitaka Tsuruta (Bombjack, Solomon's Key)

My nickname appears in the end credits of Captain Tsubasa 2. Tecmo only allowed you to have your penname or pseudonym appear in the credits. If you're still working on the game, you could request your pseudonym would appear in a particular scene. But I had already left the company, so someone told me not to worry, they put my name in the credits and showed me the scene. But that scene involved a funny character having a ball fly over and hit him in the face. And I thought that was just awful! <laughs> I wanted to get that changed but couldn't do anything about it.

As for why Tecmo used nicknames... Tecmo was a company that was very fearful, very afraid of having developers leave the company. So if you used your real name, there was the risk of being headhunted. So the company banned developers from using their real names, as well as being in contact or having any kind of exchange with other developers.

I think I can say this now - shortly after I left Tecmo, several developers from different companies got together and went for a drink. And we talked a lot about how our respective companies were treating us so poorly. If management ever found out that we got together, we would be yelled at. Management was very afraid that developers would have some kind of connection.

Kazuma Kujo (In The Hunt, Metal Slug)

For several games, I am credited under my nickname. At that time, the vast majority of Japanese companies did not allow you to put your real name in the credits; Japanese game companies were closed off and insular and prohibited the disclosure of staff's real names. That's why we used nicknames. Certainly for Kaitei Daisensou, because I was the director. But I'm also credited for some other games as planner.

I think I was always quite angry when I was in my 20s. I was frustrated about my shortcomings as a game developer and also about things that didn't go as I wanted them to. So that's why in my 20s, I had nicknames like Oni, or Kire, or Tsumi, because I was angry. Oni is an ogre, or demon. Kire means anger, or it can mean snapping. Tsumi means sin, or wrongdoings.

Kotaro Uchikoshi (999, Virtue's Last Reward)

In 2003, I did "secret work". I can talk about it, but there's a very simple reason I describe it as secret work. It was an adult game! I wrote the scenario to an erotic visual novel. <laughs> It was published, but not with my name.

What was the title... <laughs> Honestly, I'm not really hiding it, I just can't remember it. The title... What was it? As soon as I remember I'll tell you! <laughs> I was freelance. My name was not credited, and it was at my request!

Ryuichi Nishizawa (Westone co-founder, Wonder Boy creator)

Before I launched Westone, my nickname in the game industry was Bucha. <spells it: B-U-C-H-A, pronounced similarly to butcher> So whenever I played games and I hit a high score, I would enter this nickname, Bucha.

At UPL, as I mentioned, I created three games, and the tradition at UPL was: at the very beginning of the game, when the power is first turned on, the developer's nickname would show up. So as the number one high-scoring player, my nickname Bucha would show up, at the start.

Kotaro Hayashida (Alex Kidd)

I never showed my face to the media back then, and I still don't. <laughs> Back in the day, Sega forbade us all from appearing in magazines, it was a policy towards employees, and I guess that's stuck with me... Nowadays, though, Sega's scrapped that policy. If only I'd been allowed to appear in the media when I was younger!

Sega didn't see the need for a single developer to take the spotlight for a certain product, but rather felt that the company should get the credit. If they gave too much attention to the creator of a hit title, there was always the possibility that another company would come to take that creator.

Of course, I want to be recognized for my work, but not everything about becoming famous is good.

Yuzo Koshiro (Revenge of Shinobi, Streets of Rage)

It was actually my mother's idea to have my name credited and displayed on the screen! <laughs> As I described, there were some difficulties with Falcom, and I think my mother had that in mind as well. I think my mother always had the idea that the composer should have rights. I think she felt the same way for games, that composers should declare their rights for the music that they compose.

Jun Nagashima (Popful Mail, Ys V)

When I joined Falcom, there was a shortage of programmers, so I helped Kazunari Tomi on Dinosaur, the game he was developing. After finishing development on the PC-9801 version, Tomi-san quit the company, without even waiting until the game's release. At Falcom back then, it was forbidden for programmers to insert staff credits into their games. However, Tomi-san broke this rule and inserted staff credits into Dinosaur! But since Tomi-san quit before the game's retail release, another programmer went in and deleted the credits! Tomi-san was friendly and easy to talk with.

Many people quit Falcom around this time.

Aziz Hinoshita (Athena artist, Square-Enix localiser)

We outsourced our QA at Athena. You might have heard of Tose? They also have programmers, and they develop games. They're like, <laughs> well, I'm not sure if the analogue is appropriate, but they're like sweatshops. In the sense that they do all the hard lifting, but they're hardly credited. I mean, they do all the grunt work for a lot of titles.

A lot of companies in Japan actually do use them for a lot of things.

Kensuke Takahashi (Zainsoft Company, Dios)

Even as 60 people joined Zainsoft and then quit, I stayed on for four years. We never had time to put credits in, because the masters were taken away from us before we were finished. We always felt that the games were unfinished.

Game studios are not like ordinary companies, especially back then. The reason so many young people were still willing to join is because they were passionate and really wanted to create games. I think most of the 60 people that came and went experienced considerable stress from being denied the chance to finish their games.

So there you have it, readers. Japanese game publishers did not want staff credited mostly so as to maintain control over them and profiteer off their labour. But also, sometimes, it was because they made pornography. Sadly, Mr Uchikoshi never did get back to us on the title of that erotic game...

It's also worth noting that not every single game company refused to credit staff. Nintendo credited its employees, even though Shigeru Miyamoto was at one time incorrectly translated as Shigeru Miyahon, and some companies, in fact, championed the names of staff to bolster publicity.

When you compare how different developers treated people, specifically with regard to credits, it reveals a lot about the internal culture of that specific company. Thankfully, things have gotten a lot better since the 1980s and 90s, and with fan-reactions on social media hopefully, we'll see things continue to improve. Keep it in mind the next time you finish a game and watch the names roll by.

In the meantime, let the developers and publishers of the world know they are on report, and Time Extension will be keeping vigilant in case of any transgressions.