2022 marked the return of both the beloved Monkey Island series (via the amazing Return To Monkey Island) and its creator, Ron Gilbert. While he famously walked away from the franchise for 20 years, there have been other adventures since then – starting 15 years ago with 1997's The Curse of Monkey Island.

Helmed by Jonathan Ackley and Larry Ahern, the first non-Gilbert Monkey Island told the story of Guybrush Threepwood, a "mighty pirate", trying to restore love interest Elaine Marley, who he inadvertently turned into a gold statue with a cursed engagement ring – whilst also contending with the evil ghost pirate LeChuck.

Ackley and Ahern had both worked on previous LucasArts adventures Day of the Tentacle and Full Throttle, although not directly together – Ackley had been on the programming side of things, while Ahern was a member of the art team. In fact, it was the studio's management that put the pair together and gave them the chance to lead a project together, suggesting a new Monkey Island.

"It was pretty customary at LucasArts for them to start new project leaders as pairs, which is why you had Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman working together on Day of the Tentacle, Mike Stemmle and Sean Clark on Sam & Max Hit The Road," Ackley tells us. "After Full Throttle, there was the question as to whether you could do a game the size of Day of the Tentacle or The Secret of Monkey Island with modern production values. It would have been a huge pain for either one of us to attempt this individually. In order to pull it off without the production spiralling out of control and becoming an over-budget disaster, we had to be really organised with art and programming and writing all working together. It was a great partnership, and Larry is one of my favourite collaborators."

Ahern adds: "We had a lot of fun, and we've worked together quite a bit since, so it was a good combination that management suggested."

When Curse of Monkey Island was announced in 1996, the series had been absent for five years – and a lot had changed in the PC gaming space. Fortunately, the two leads could draw on their past experiences; Ahern's first title had actually been Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge, and Maniac Mansion sequel Day of the Tentacle had proven to be especially useful. As with that game, this would be a case of presenting updated versions of established characters with a solid formula to follow.

"You didn't necessarily have to match what came before because everything had changed anyway," Ahern explains. "So I wasn't too panicked about it – but then the internet didn't really exist to yell at us back then, so that wasn't something we had to worry about."

Guybrush Meets Paintbrush

There was, however, some yelling via message boards. When fans found out the new Monkey Island wasn't being made by Ron Gilbert, they were "kinda looking for reasons to dislike the game," Ackley says, and began spreading rumours – which led to one of the game's best easter eggs.

Fans claimed that Curse would use SCUMM 3D, taking Monkey Island away from its 2D roots. Ackley says two "brilliant and grumpy programmers" – Chris Purvis and Chuck Jordan – decided to troll the internet back, adding the 'Enable 3D acceleration option to the menu screen for "super-special 3D SCUMM environments." But clicking it only presented messages ranging from "We were only kidding" to "You can click that all you want, it won't do anything."

Ackley confesses he feels a little bad about this joke, however. "After the game came out, the support team received a letter from some poor gentleman had tried swapping out several video cards to get SCUMM 3D to work – and ended up bricking his computer," he says with a smile.

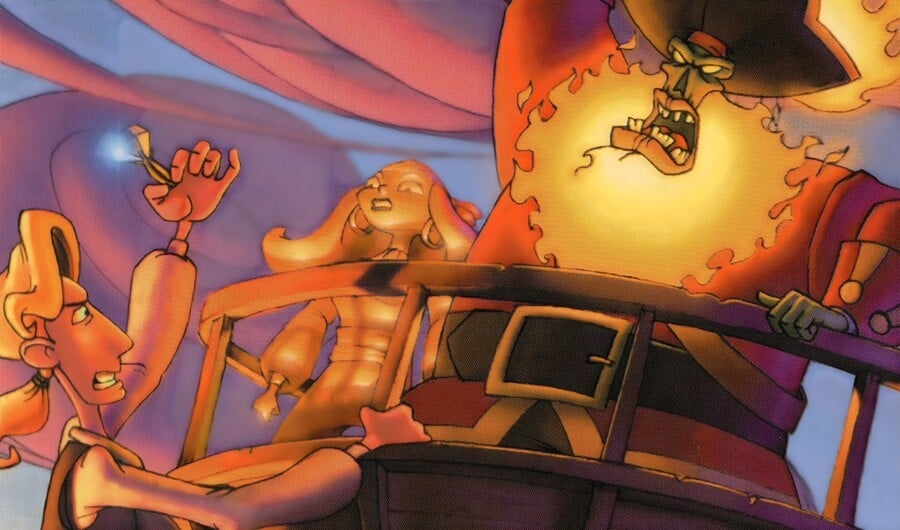

Instead of the newfangled 3D that had become all the rage in the mid-to-late Nineties, Curse of Monkey Island featured a stunning, hand-drawn animation style. According to Ahern, lead background artist Bill Tiller drew inspiration from the 'Disney Renaissance' occurring at the time, as well as classic pirate illustrations by artists like Howard Pyle. Since LucasArts could now render a game in higher resolution, the team wanted it to feel like an animated film.

After the game came out, the support team received a letter from some poor gentleman had tried swapping out several video cards to get SCUMM 3D to work – and ended up bricking his computer

"We also looked at the evolution from the first to second Monkey Island game," Ahern continues. "They got a lot more painterly and colourful in the second game, but the technology meant it all got a bit more pixelated. They did some coloured marker art they scanned in and hadn't really fully figured out the process of how to make it look gorgeous like the original piece."

Fortunately, the solution to this had largely been worked out with Day of the Tentacle. Tiller originally leaned towards a more watercolour style, but Ahern says it "felt a little too washed out." By the end of the process, Curse of Monkey Island was designed around more intense colour with some dramatic lighting – "That was the look we got excited about," Ahern says.

With the new style decided upon, Ahern – who also served as art and animation director – oversaw the process of redesigning the classic characters. He observes that, due to the nature of the 8-bit graphics, the original versions were so small they barely resembled their box cover counterparts. This was a chance to create a more unified look. On reflection, the two project leads say that some characters were more successfully redesigned than others – LeChuck remains a favourite – although Ahern is not entirely happy with Guybrush.

"And I know there have been a lot of complaints over the years," he laughs. "I just didn't get it quite right. I felt like the tone of the Monkey Island games was a little more comedic than some of the earlier images of Guybrush, like the box cover. So I wanted to get a little more goofy with it – similar to how I got a lot more cartoony going from Maniac Mansion to Day of the Tentacle. It makes it clear this is a comedy."

Ackley adds that full animation overcame another challenge of the first two Monkey Island games; since faces were essentially "five rectangular pixels, with a dot for an eye and another for the mouth," characters could not act. Whereas the more cartoony style, and especially the larger head, meant Guybrush could react and be more expressive throughout his adventure.

Darragh said the guy was driving his agent nuts, going 'you don't understand – I AM Guybrush Threepwood,'" Ackley recalls. "And we were like, 'yeah, sure buddy'. It was Dominic Armato. We listened to the tape, me and Larry looked at each other and were like, 'Yeah, that's Guybrush.'

A prime example is his unamused face during the pirate shanty at the halfway point. Interestingly, Ackley says that, while this is a highlight of the game for many, this scene was nearly cut because the actors couldn’t sing.

"Dominic [Armato, who voiced Guybrush] was the only guy who could carry a tune, but the others – who were all fabulous character actors – were the worst singers ever," he recalls. Thankfully, he adds, composer Michael Land was "a musical genius" and managed to create an edit that hid their poor performance.

This raises another crucial difference between Curse and its predecessors; this was the first fully-voiced Monkey Island. Darragh O'Farrell was in charge of casting and directing the chosen actors, and the team even managed to land some established talent, including Gary Coleman and Alan Young (AKA: Scrooge McDuck).

As with character design, the game's protagonist proved to be the trickiest, with Ackley saying they rejected several actors because "you'd either get generic hero guy or super nerdy, nebbish guy." Seeking more of a "Michael J Fox type of thing," the project leads were sent one last audition tape.

"Darragh said the guy was driving his agent nuts, going 'you don't understand – I AM Guybrush Threepwood,'" Ackley recalls. "And we were like, 'yeah, sure buddy'. It was Dominic Armato. We listened to the tape, me and Larry looked at each other and were like, 'Yeah, that's Guybrush.'"

Modernising Monkey Island

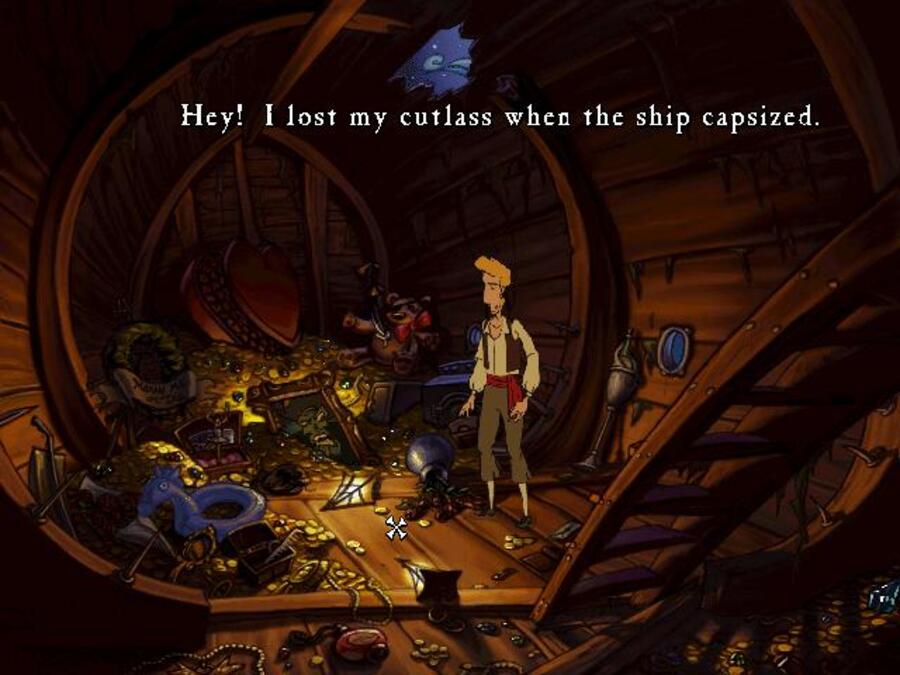

While defining the look and sound of a new Monkey Island was challenging, the "weighty responsibility" of making a new entry in the series centred mostly around the feel of it. The first two titles typify the classic LucasArts adventure game style, but the days of nine-verb interfaces were gone and the team had to find a way to draw on the studio's more recent titles while enabling all the possibilities of the originals.

For example, the verb system was dramatically simplified, reduced from nine to three and organised into symbols on a coin-style menu. The hand was used for push, pull, open, pick up and so on. The skull handled any actions to do with the eyes, such as looking. The parrot represented the mouth, mostly for talking. This may have seemed jarring to longtime Monkey Island fans, but it made the game's mechanics more accessible.

Curse of Monkey Island could have been built around the simpler interface of Full Throttle, but that title didn't allow players to use inventory objects with each other – a crucial aspect of Monkey Island puzzling (and Curse had over 100 items for Guybrush to handle). The team also needed to allow players to make the wrong combinations and the comedic responses this would trigger.

"One of the design philosophies that Larry and I subscribe to is rewarding failure," says Ackley. "Adventure games are built on punishing the player over and over again. In a way, it's a bit of an unfair genre because until you guess what Larry and I were thinking, you can't go anywhere. So we might as well treat you kindly while you are stuck by writing a joke for absolutely everything in the environment."

I'm not worried that I'm going down the wrong branch in a conversation because I know there's going to be a punchline. In fact, I'll check all the wrong ones anyway because I don't want to miss those punchlines

Ahern adds: "That's similar with the interactive dialogues. In a dramatic game, it can feel painful, but in a comedy, I'm not worried that I'm going down the wrong branch in a conversation because I know there's going to be a punchline. In fact, I'll check all the wrong ones anyway because I don't want to miss those punchlines."

Perhaps the best example is Murray, the self-titled 'All-Powerful Demonic Skull'. Cropping up throughout the game, very few of his conversations advance the plot or allow Guybrush to progress, yet he remains one of Curse's most memorable characters. Written mostly by Ackley, Murray was originally known as 'Floating Skull', and the only reason he existed was a problem with the game's design.

"The interface of Myst, which was popular at the time, just comes to down clicking on everything – which means can do anything and go anywhere you want on this big island," Ackley explains. "We had to teach players the interface before turning them loose on our first island. So we had to start with a 'Guybrush locked in a room' puzzle – it's not a great game design way to start a game, but we had to show you how to use inventory items and all these other things."

As such, Guybrush starts Curse of Monkey Island as a prisoner in the brig of LeChuck's ship, seeking a way out. To make it more engaging, the team needed to give Guybrush someone to talk to; Monkey Island 2's Wally returns here, but he quickly becomes unavailable for conversation. So, following a short sequence in which he blasts boatloads of skeletons with a cannon, Guybrush finds himself leaning out of a porthole, conversing with a now-disembodied skull.

In the original draft, Murray/Floating Skull was "unlikeable and mean," according to Ahern. Eventually, rewrites got to the core of why Murray is so beloved: ultimately, he's a delusional optimist. "His threats in the original version were like 'You're pathetic Guybrush, you'll never amount to anything, you'll never get out of there', which is just sad and disappointing, and you don't like the guy," Ahern explains. "But when it's 'I'll stride through the gates of hell carrying your head on a pike… okay, fine, ROLL through the gates of hell,' he's still evil, but now you're rolling your eyes. This guy can't do any of that, but good for him for thinking he can."

Ackley adds: "He's not really a grumpy guy, he just won't be kept down by the fact that he has no hands, legs or body."

Murray became so popular that the duo sought to include him throughout the game – despite the bulk of the plot and puzzles being in place. This is why the character has little impact on the course of the game; Ackley and Ahern say they essentially went through each scene looking for background skulls that could be replaced with another Murray encounter.

SCUMM And Villainy

The Curse of Monkey Island was a milestone for LucasArts in many ways. For a start, Ackley says it was the studio's first "high-res" (note: he even makes the 'air quotes' motion) titles at 640 x 480 with a full-screen interface. It was also the most technologically advanced, with features such as a primitive version of anti-aliasing; while other cel animated games at the time had 'stair-stepping' around the lines of the characters, Curse's cast were more smoothly integrated into each scene.

A lot of this came from the combined experience of the team, who by this point were well-versed in the studio's proprietary SCUMM engine, which had been overhauled in the run-up to work on Curse.

We pulled out all the tricks that SCUMM allowed, so I think we exercised the engine more than previous games had – which I think leads to the game feeling smoother and more unified

"It wasn't necessarily just the improved tools, but we were using the tools differently than they had been used before," Ackley adds. "There were things that ordinarily used to be handled within the SCUMM system, but we wanted greater control and greater ability to customise the presentation of things, and we pulled that functionality out into the scripting side of things. We pulled out all the tricks that SCUMM allowed, so I think we exercised the engine more than previous games had – which I think leads to the game feeling smoother and more unified."

He offers the example of character scaling; in Curse, this was handled by scripts rather than the SCUMM engine itself to ensure Guybrush shrank and grew with distance, and fit into each room – even a shadow was added if he walked under a tree.

SCUMM had been created for the original Maniac Mansion (as we all know, it stands for 'Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion'), and had been powering LucasArts games since 1987 – but Curse of Monkey Island was to be its final outing.

"I think we were victims of our own ambitions," Ackley says. "Every time we did a SCUMM game, we wanted it to be bigger and better. So it became more expensive, but the target demographic that bought adventure games wasn't growing. Meanwhile, you had 3D games that were suddenly technologically viable, and they were exploding in the marketplace."

Ahern adds that he and his partner did pitch a 3D follow-up to Curse of Monkey Island, but management believed there was not enough justification for the 3D. The appeal of 3D was navigating a dimensional space, but that appeal was lessened if players were simply going through to pick up an inventory item. "And, of course, we didn't want to be shooting everything," Ahern adds.

Ackley recalls going into the programmers' office after Curse was released and seeing members of the team playing a 3D game that was also doing deep storytelling. "That game was Half-Life. I realised the age of 2D shoebox characters was over. Our games were fun and cute, but it was definitely going to go this way. We were lucky to be the last SCUMM game, and I think we went out on a good note."