When you think of the key names in the history of video games hardware, a few notable monikers spring to mind. Nintendo is obviously one of them; the Japanese veteran has been a major part of the industry since the '80s, and has maintained a position of importance and influence despite numerous challenges from rivals. Speaking of which, Sega is another name that crops up; while the company no longer dabbles in video game hardware outside of the odd arcade machine, it was, for a long time, Nintendo's main competitor.

Then there's Atari – the company that arguably did the vital pathfinding in the realm of home video games that allowed companies like Nintendo and Sega to flourish. Atari created the first truly mass-market home gaming system in the shape of the VCS (later renamed the 2600), and also pioneered the concept of licencing the software of other companies when it paid Taito for the rights to port Space Invaders to its console. It even inadvertently created the concept of third-party publishing when it treated four of its key staffers – David Crane, Larry Kaplan, Alan Miller and Bob Whitehead – so poorly that they decided to leave and set up Activision, the first video games company of its kind.

However, despite its success in the '80s, Atari made some pretty sizeable blunders, both before and after the infamous video game crash of 1983, where the market collapsed after a flood of poor-quality games were released for the ageing VCS – a console that, by 1982, was beginning to seriously show its limitations. The irony is that two of its biggest mistakes could have potentially pulled the company from the brink at two separate points in its history.

Back in 1982, the industry was in a strange place. The Atari VCS was the undisputed champion of the home gaming arena and 'Atari' had become almost interchangeable with the term 'video game'. The company was selling millions of copies of its most popular games and demand seemed insatiable, but the bubble was about to burst. When Atari posted lower-than-expected earnings projections, the seeds of the crash of '83 were sewn.

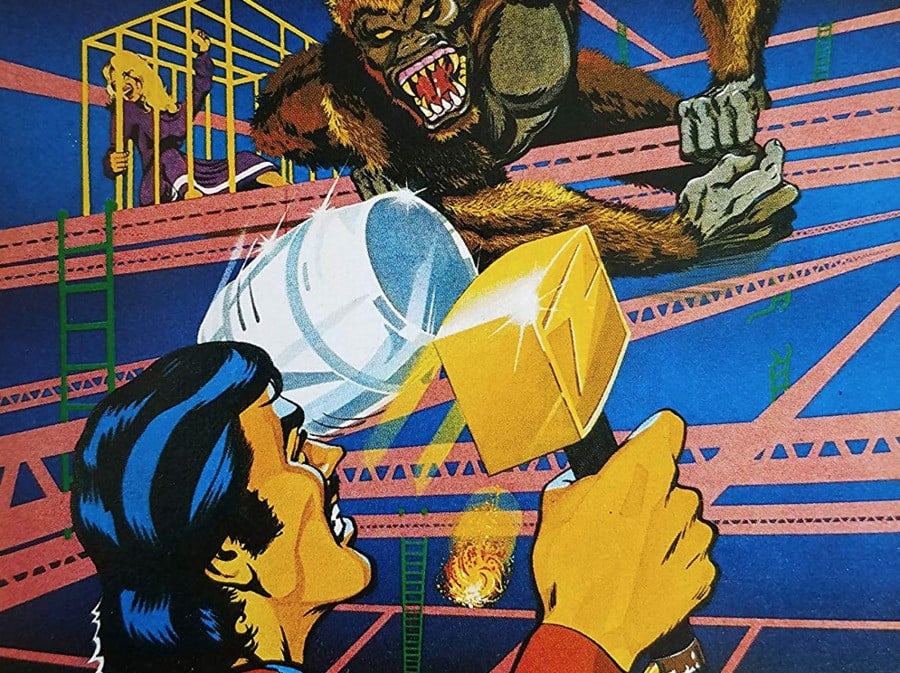

Over in Japan, Nintendo was working on the Famicom home console following the runaway success of its Donkey Kong arcade machine – the make-or-break release that truly put the company on the map in the world of interactive entertainment. Hiroshi Yamauchi, the savvy yet prickly boss of Nintendo, knew that success in Japan was only one part of the puzzle. The firm's real gains had been made in the United States via the aforementioned Donkey Kong coin-op, and any home hardware it released would need to be released in America to maximise its potential. The issue was that Nintendo, despite scoring a hit in arcades, was still relatively unknown in the U.S. and lacked the infrastructure and experience to release a home console in that region. To solve this issue, it turned to Atari.

In early 1983, Yamauchi instructed Nintendo of America vice president Howard Lincoln to call Atari and discuss the possibility of the two companies working together to launch the Famicom stateside. Given that this contact occurred months after Atari CEO Ray Kassar had announced that the company's sales goals had been missed – and that Atari's attempts to create a successor to the VCS had stumbled (the 5200 SuperSystem was unimpressive, while the 7800 ProSystem wouldn't hit the market until 1986, despite being ready for release years earlier) – this was a dream deal on paper. Nintendo basically offered Atari the opportunity to sell the Famicom under its own brand in exchange for paying Nintendo a royalty on every console.

It was a done deal. We had the whole thing put together

Atari effectively had nothing to lose; it was unknown at the time if the still-in-development 7800 was more powerful than Nintendo's console, but by licencing the Famicom it had a solid back-up plan that would cost it nothing in terms of R&D. A meeting was quickly arranged, and Lincoln – along with Nintendo of American president Minoru Arakawa – was flown to Atari's California HQ to draft out the deal. Negotiations took days to resolve, and when Lincoln warned that Yamauchi – not a man famous for its reserves of patience – was growing restless, Atari boss Kassar gave final approval to the deal. Atari would distribute the Famicom under its own brand in North America, and would potentially enable Nintendo to get its product into millions of households all over the country. "It was a done deal," former Nintendo of American president Howard Lincoln told video game journalist and historian Steven L. Kent some years later. "We had the whole thing put together."

As we all know, it didn't quite pan out that way. At CES 1983, Coleco – the firm behind the ColecoVision home console, a key VCS rival – demonstrated its Adam home computer. Based on the same core tech as the ColecoVision, it was capable of running ColecoVision cartridges – and that included Nintendo's crown jewel, Donkey Kong. Nintendo had licenced the game for release on the ColecoVision console and duly used this title to promote the Adam computer – the fact that it was capable of playing games was seen as a key selling point.

However, Atari had purchased the home computer rights for the game, and when Atari representatives saw Kong running on a rival computer, it was instantly assumed that Nintendo had broken its agreement. "You have to understand that Donkey Kong was the main reason anyone would be interested in working with Nintendo," Howard Philips would tell Kent. "Mario Bros. and our other games were good B-titles, Super Mario Brothers had not come out yet, and the only game that did better than Donkey Kong was Pac-Man. If Coleco had Donkey Kong, Atari had no reason to work with us."

You have to understand that Donkey Kong was the main reason anyone would be interested in working with Nintendo

Nintendo, for its part, had no idea that Coleco was using Donkey Kong to showcase the Adam, and Coleco, in its defence, wasn't promoting a home computer version of the game – which is what Atari owned the rights too – but was instead showing off the fact that the Adam could run ColecoVision cartridges. An emergency meeting was swiftly arranged between Atari, Nintendo and Coleco, and Coleco agreed to stop demonstrating Donkey Kong with the Adam, or bundling it with the machine. However, while the deal was saved, it ended up being somewhat moot; following revelations that he had offloaded 5,000 shares of Warner Communications stock prior to the announcement that Atari's profits were going to be lower than expected, Ray Kassar was forced to resign from his position as CEO of Atari and the revised Nintendo deal remained unsigned. With the key supporter of the deal within Atari now out of the picture, things ground to a halt.

With the Atari deal seemingly dead in the water and the Famicom selling impressively in Japan, Nintendo decided to go it alone and release the console in the states as the Nintendo Entertainment System, a machine which would not only change the face of gaming worldwide and establish the Japanese company as a global leader in the realm of interactive entertainment. The struggling Atari, on the other hand, would be sold by parent company Warner Communications to former Commodore boss Jack Tramiel in 1984, creating Atari Corporation.

Despite the change of ownership, you'd think that Atari would have been more mindful of making a similar mistake down the line. However, history repeated itself quite neatly towards the end of the '80s; Sega, having failed to even dent Nintendo's stranglehold with its 8-bit Master System, decided to break ties with North American distributor Tonka and court other partners. While it felt it could comfortably handle the Japanese launch of its next system – the 16-bit Mega Drive – on its own, Sega was mindful of the fact that cracking North America was a different proposition entirely. It needed a US company which had experience in the field as well as a distribution and marketing network already in place, and it turned to – you guessed it – Atari.

"[Sega chairman] Dave Rosen came to Atari and asked if we’d be interested in taking over the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of Genesis," Michael Katz told Steven Kent. Katz was then the president of Atari Corporation's video game division, and had been instrumental in helping Atari to its best year since 1982 in terms of earnings; the Atari 7800 console had carved out enough of a share of the market to propel the company towards a revenue total of $452 million in 1988. "We came very close to making a hefty licensing deal so that Atari could jump into the 16-bit fray before Nintendo," Katz adds. "The negotiations went pretty far down the stream, and as I recall, they fell apart when Jack Tramiel and Dave Rosen couldn’t agree to the terms. Then Sega decided to do it themselves."

We came very close to making a hefty licensing deal so that Atari could jump into the 16-bit fray before Nintendo. The negotiations went pretty far down the stream

Sound familiar? Once again, Atari managed to grab defeat from the jaws of victory. Sega would follow Nintendo's lead and release the Mega Drive (or Genesis, as it was known in North America) itself, stealing away market share from the ageing NES and establishing a rivalry with Nintendo that would last all the way through the 16-bit era. Ironically, Katz would be one of the people who helped shape this legacy – he joined Sega in 1989 following a job offer from Rosen, and oversaw the iconic "Genesis does what Nintendon't" advertising campaign that enabled Sega to gobble up so much of the North American market. Katz was also a vital figure in Sega's drive to sign up sports stars such as Joe Montana, Arnold Palmer and James "Buster" Douglas to appear in Genesis games – another important factor in the console's early success.

Atari, as we all know, stumbled from one disaster to another. The Atari XE computer flopped, its Lynx handheld was powerful but overpriced and the much-hyped Jaguar home console failed to find an audience. The company's relationship with Sega took another twist in 1994 when it signed a deal over usage of Atari patents in Sega titles – a deal which was supposed to allow Atari to use Sega IP on the Jaguar – but two years later, the company effectively ceased to exist. The Tramiel family wanted out of the video games business, and in July 1996, Atari was merged with hard disk drive manufacturer JTS Inc., and the iconic Atari logo all but vanished from view. Toy company Hasbro bought the rights to Atari's IP in 1998 for $5 million, and since then the brand has been passed around various owners. The 'Atari' of today is looking to reinvent the VCS as a multimedia set-top box and is even getting involved with the hotel business.