There are few people who have had quite as much impact on the video game industry as former Sega and Atari president Michael Katz.

After stints at marketing agencies like The Lever Brothers and McCann-Erickson, he became integral in launching the industry's first handheld electronic toy line as Mattel's marketing director for new categories in the late 70s. After that, he then moved to Mattel's competitor Coleco to take on the role of vice president of marketing from 1979-1983, where he helped the company release a more advanced line of portable electronic toys, as well as the popular home console ColecoVision. That would be enough of a claim to fame for some people, but Katz's career in video games was only getting started.

Following a few years in the wilderness of computer software publishing as president of Epyx (the publisher of Impossible Mission, Summer Games, and Winter Games), Katz returned to the hardware side of the industry in '85, joining Atari as its new president under its controversial owner Jack Tramiel. There he helped Atari gain back some relevance before being enticed to leave the iconic brand to lead Sega of America in its battle against Nintendo in late '89.

Under his one-year presidency at Sega, he started several important initiatives, which have commonly been misattributed to his successor Tom Kalinske, including increasing the number of sports titles that Sega published, overseeing the founding of Sega of America's development division, and greenlighting the memorable ad campaign: "Genesis Does What Nintendon't". It was under his leadership that Sega firmly established itself as the number-two video game company in the US, laying the groundwork for the company's future success. Time Extension recently spoke to Katz about his impressive career. What follows is our conversation edited and condensed for flow and clarity.

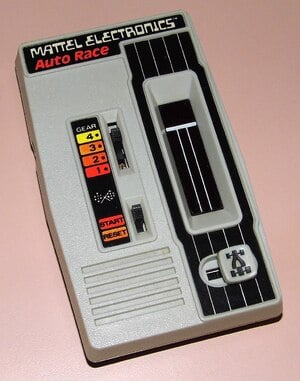

Time Extension: You started your career in games at Mattel in 1975, where you helped launch the electronic handheld category of Mattel’s business with Auto Race. How did that all come about?

Michael Katz: Well the conception of that was everyone knew that the portable calculator, the LED portable calculator, was not only practical but kind of fun to fool around with and see the LEDs light up and all that. So I said to the design group headed by a guy named Richard Chang, ‘Can you design a game based on electronics and based on portability and based on LED technology?’ Two weeks later, he came back with an obstacle avoidance game in prototype form where you tried to move an LED from the bottom of the screen to the top of the screen without hitting anything in terms of oncoming LEDs or having the oncoming LEDs interrupt you and block you out.

We looked at that and said, ‘What can that be in terms of sports?’ And we developed a lot of themes that we then tested and the themes included a football running back trying to get to the goal line but tacklers coming after them, a car in an auto race trying to go through other cars, basketball players, etc, etc. The most popular theme was football, but we knew we had a better prototype of a football product based on the technology coming along, so we took the second most popular, which was Auto Race, and the first handheld electronic game ever in the industry’s history became Mattel’s Auto Race.

I took it around, showed it to retailers, and we did research with people. It was revolutionary and a lot of retailers wanted it. But a lot of retailers also said, ‘Let’s wait to see if it catches on.’ That was the story at Sears, which was one of the hottest toy retailers at the time. [Elsewhere] Toys R’ Us took it, KB Toys took it, and K-Mart took it. Walmart waited a year because they don’t take products initially. They wanted to wait and see if they were going to be successful.

Anyway, that became the beginning of the world’s first handheld electronic game line. I like to think it preceded mobile gaming today, and of course, it led to the whole category that Tiger Electronics was in, that Hasbro was in, and that Mattel started, and that was our biggest success in terms of volume and profitability when I was in charge of that category.

Time Extension: After Mattel, you joined Coleco in 1979, I'm curious — what made you want to make the move across to one of Mattel's competitors at the time?

Michael Katz: I had been at Mattel for four years. It was a company that was fairly structured and established in terms of salaries, bonuses, and all that and I wasn’t running the show. I wasn’t the vice president. I was just the director of a category. So Arnold and Leonard Greenberg, who were the founder’s sons at Coleco (which stood for Connecticut Leather Company) said ‘Hey, I’m interested in this category that Mattel has started, let’s get into it’. He copied the product with Electronic Quarterback and he said, ‘Let’s get someone who knows those categories’ so they asked me if I wanted to be the first head of marketing at Coleco and build electronics.

Eventually, we had some real, big hits, because we had ColecoVision, Cabbage Patch Dolls, and the handhelds. Coleco was the fastest New York Stock Exchange company on Wall Street in 1983. The stock went from 7 to 50, which was a big deal in those days. It’s not a big deal anymore.

Time Extension: Speaking of the handhelds, you found yourself in a bizarre position when you joined Coleco where you had to immediately start advertising the company's new, more advanced Head-To-Head sports line against Mattel’s, which you had previously been responsible for. There was even a commercial directly comparing the two. Could you talk a little about that?

Michael Katz: That was the first competitive commercial that was done for handheld games. The first and maybe the most successful. The first week I got to Coleco I was shown the storyboard for the commercial and asked to approve it. And here I was the guy that had started handheld games at Mattel being asked to approve a competitive commercial against the Mattel handhelds. That was really ironic.

It was done at the ad agency at Coleco, which was known as Richard & Edwards. They're now defunct, but one of them was a copywriter and the other was an accounts/business type person. They came up with the concept and they should get credit for it. I don't think they've got much credit over the years for being the first with a competitive commercial for portable games, but they deserve it.

Time Extension: Coleco launched the ColecoVision console in 1982 in North America and it was obviously a huge success for the company, but I’ve read a few articles from the time that were skeptical that ColecoVision would do well. They mentioned potential supply shortages that had been an issue with Coleco's Telstar products in the '70s. Were shortages an issue you can remember? And could ColecoVision have sold more than it did?

Michael Katz: Good question. I think, no. There weren’t any significant shortages on an ongoing basis that I recall. But I do believe historically reporters and retro writers don’t give enough credit to Coleco for ColecoVision. It’s hardly even mentioned in some of the books and articles as being a dominant product that was really a next-generation product.

To Arnold and Leonard’s credit, they decided to come out with a new piece of hardware, not just make games based on arcade hits for existing Intellivision and [Atari] hardware.

We, meaning the marketing department and me, thought it was risky at the time to introduce a new piece of hardware because of the investment involved and you don’t make money on hardware, but Arnold Greenberg said, ‘No, we’ve got Donkey Kong, it’s the hottest arcade game, let’s come out with a [new] system and let’s include Donkey Kong with the system as an incentive to purchase the system and I think we’ll have a winner.’ And he was right. It was the software that sold ColecoVision, and ColecoVision allowed the games to look and feel much more like the arcade than ever before.

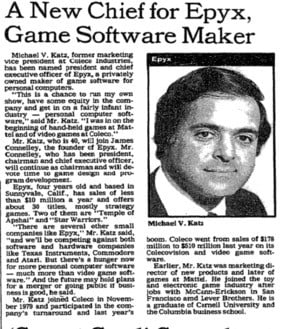

Time Extension: After four years at Coleco, you left for Epyx in 1983, which was a small computer publisher that wasn’t doing particularly too well at the time. Why did you make that decision?

Michael Katz: Well, the progression was I left Mattel which was a major company — very successful — but just a salary job with a bonus, no stock, and no equity. I left to go to Coleco to be a vice president of marketing and get a lot of stock options, which became a lot while I was there. And my next step was to return to the west coast.

I was divorced and my kids and family lived on the west coast. And my goal had always been, after getting some equity and making it worth something in a place like Coleco, to go back to Silicon Valley, which was not the Silicon Valley of today — it was much smaller but still important – and get a job as a CEO of a small venture capital funded company and get at least 10% of the stock and really have a nice ride.

That was what I was approached with by headhunters representing 5 or 6 venture capitalists who were all board members of Epyx. I had never heard of Epyx. I was not interested in computer games, because I’m not a computer guy and I’m not an engineer. I was more interested in the mass market, fast game systems, and software. But the appeal was once again a company was having problems.

Epyx was losing money, they were only doing about, I think, $2 million to $3 million in sales, or $1.5 million, and losing money. My orders from the venture capitalists, who were the owners, were to make it into a mass-market company like Coleco, Mattel, and Atari, with action-oriented products that relied on animation, not text or strategy, and appeal to a broader audience.

That got me back to California and I became CEO of my first company and got 10% of the stock. That was the incentive.

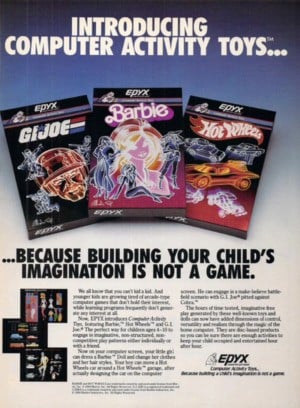

Time Extension: Shortly after arriving at Epyx, the publisher started a line of licensed games based on popular toys like G.I. Joe, Barbie, and Hot Wheels. Was that part of your plan to turn the company into one with more mass-market appeal?

Michael Katz: I got the license from Hasbro and Mattel where I knew the people, so it helped. And we were the first computer game company, which very few people realize, to license Hot Wheels, Barbie, and GI Joe for computer software.

When I got to Epyx, we wanted to expand the genres of software into the most popular selling categories. One of the categories that we had when I was in the toy industry was ‘Activity Toys’. Not games, but Activity Toys. Activity Toys were basically playing an activity with no win or lose criteria, which would make it into a game, but it was an activity just like playing with toy soldiers or playing with dolls. My concept was we wanted to have an activity toy category, we wanted to have something involving dolls, and we wanted to have something involving soldiers because toys and games are real-life in miniature.

So when people are playing with dolls, they’re actually being the mother of a baby, and when they’re playing with toy soldiers, they’re actually pretending to be soldiers on a battlefield. So the concept was we wanted the genre of Activity Toys looking at dolls and soldiers and cars, which automatically meant brand-wise trying to get the license for Barbie and Hot Wheels from Mattel and GI Joe from Hasbro.

Time Extension: In 1984, 14 Eastern Bloc countries boycotted the California Olympics around the time that Epyx was getting to release the sports title Summer Games. I found a few interesting news articles about Epyx sending copies to Soviet ambassadors for the US and the UN at the time. I’m just wondering, did you ever receive a reply back from any of them?

Michael Katz: Good question. I was reminded of that 5 or 6 years ago. We did it as a PR move, so we could publicize it. And I think we did receive a response from at least one embassy thanking us for the prototypes and wishing us good luck.

The story there was Bob Brown, who was the head engineer at Atari for the 2600, had started a computer game company called [Star Path], and Epyx bought Bob Brown’s little 7- or 8-person company. One of the products they had on the shelf was a multi-activity sports game. When I saw that, it was still not finished, but we knew that a year and a half later or a year later the Olympics were coming up. So it was a natural fit to try and make that into an Olympic product. The only questions revolved around how good the events could be, how many events could we include, how realistic could they be, and whether we were going to get in trouble with the Olympic committee and stuff like that. That became Summer Games and Winter Games.

So it was Bob Brown’s product that [Epyx] got finished after we did the acquisition.

Time Extension: After Epyx, you went to another hardware manufacturer Atari in '85. A lot of the news stories I pulled up from this period, were about the broken promises that Jack Tramiel was making at Atari. I’m wondering, what was the position of Atari when you came in? And how did you find yourself coming aboard?

Michael Katz: Jack Tramiel who founded Commodore came with his three or four sons to California after buying assets of Atari from Warner Communications — just for debt.

Jack bought Atari and his sole goal and objective were to do with Atari what he had done with Commodore and that was to create at the time the world’s best, most popular, home computer. So he thought the Atari name, the Atari franchise, and the Atari technology and computers would allow him to come out with a more powerful, inexpensive hot home computer for the day than Commodore 64. That was the position they were in.

It was a goal, an objective, and a dream. And to finance the new ST computer, Jack knew he needed money, and the money was going to come from as many old Atari video games systems — the 2600 or the 7800 and the software — that he could sell. And he would use the revenue base that he got from selling those systems to finance the development of the ST computer. So they needed someone who knew games.

I was at Epyx bored stiff, just doing computer games with a small company, so they asked me to be the head of the video game division at Atari and help it make a comeback, and also, to be the head of marketing for the computer division. Jack and I eventually argued too much on how to market computers, so I said, “Jack, give it to someone else, I’ll just do the game thing, but I also want to do a new division called Entertainment Electronics. I want it to be a Worlds of Wonder-type product. So, I’ll do that and I’ll do the video game job."

Time Extension: Something that I saw mentioned in The Ultimate History of Video Games by Steven Kent — and that I've seen discussed recently — is that Atari almost took over the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of Genesis in North America while you were there. Is that something you can shed a bit more light on?

Michael Katz: Of course. Dave Rosen — who was the US chairman of Sega and was instrumental in founding Sega after World War II in Japan — felt that rather than have Sega start a US division to manufacture and market what became Genesis hardware. He’d like to do a licensing deal, and so he came to me and asked if there would be any interest in Atari licensing what became Genesis. I said, ‘Definitely!’

We set up meetings between Jack Tramiel, me, Dave Rosen, and Nakayama and Atari said ‘Yes, we want the marketing and distribution rights’ — I don’t know if it was manufacturing also.

It would have been perfect, as Atari needed a new state-of-the-art system and Atari was the biggest name in video games, so that could have represented the resurrection of Atari in the world of 16-bit game systems. So we made a verbal agreement in a meeting at Atari with Jack Tramiel and Dave Rosen. I was there; I was thrilled. And then about two weeks later, Jack Tramiel decided that he didn’t want to pay the advance guarantee in royalties that Sega was asking. He thought it was too much and the deal fell apart. And that’s when Sega decided to open a US division itself for the marketing and distribution of Genesis.

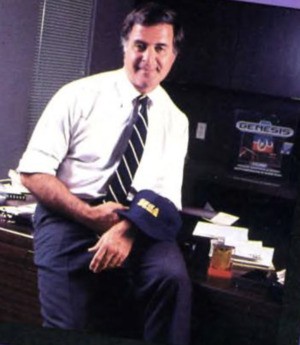

Time Extension: Not long after that, you decided to leave Atari for Sega. What were your reasons for moving across to help establish Sega Genesis in the US?

Michael Katz: I had been at Atari for four years. My stock became vested, I did what I wanted to do, and I was tired of working for large video game companies and wanted to have a sabbatical and travel. So I did for five or six months.

When I came back, I thought I would do something completely different from video games, but after finding out you get branded for what you did in the past, not necessarily what you want to do in the future, I was branded as being a video game and toy guy. Dave Rosen, who I knew, who was the chairman of Sega in the United States came to me and said, ‘We haven’t had much luck launching Sega in the US against Nintendo, we want to set up a US division, do you want to run it? And do you want to take on Nintendo with our new 16-bit system?’

I liked being the small guy, like Avis vs Hertz in the old days, and I had nothing better to do, so I said ‘Sure, let’s do it!’ [My role] was to [handle the] development, hire accounting, hire production people, work with the Japanese to determine who would develop what kinds of software, etc, etc, and launch Genesis. And we had to launch Genesis with some titles that would be appealing to Nintendo Entertainment System owners – 90% of the category was still Nintendo. We needed to get them to convert over to the more powerful Genesis.

You can’t do it by just telling them you’ve got a better system. You’ve got to have games that they want to play on the other system. So sports were big in the US, football was the biggest sport, and Joe Montana was the most famous footballer. So we competed with Nintendo [for Joe Montana] and we won. We got Joe Montana for three or four years. He was the voice of and the picture of Sega Genesis.

He made a lot on his royalties, and that really launched Sega Genesis. Not Sonic the Hedgehog. It got launched by people wanting to buy Genesis after they saw what could be done with the software quality as witnessed by a game like Joe Montana Football. Sonic the Hedgehog came [several] months later.

Time Extension: At the time, Sega and Nintendo were taking vastly different approaches to market their machines. Sega leaned far more toward celebrity marketing and celebrity endorsements. Why was that?

Michael Katz: That’s because we couldn’t get any of the hot arcade titles. They were held exclusively by Nintendo. So, we had to look for something that we could hang our hat on and so we looked for personalities and that became “Genesis Does What Nintendon’t”. We did it by process of elimination, and we knew that personalities could be hot. Not as hot as the hot arcade games, but we couldn’t get the hot arcade games.

We wanted to get the best guys in every category, so we got the boxer Buster Douglas when he was champion. He only stayed champion for [8 months], but that didn’t matter because it satisfied our product line strategy and got the game sold to retailers, because they understood we were going for the best sports people. We had a deal with him where we didn’t pay him a big advance or guarantee, which was fortunate because he lost the championship later [against Evander Holyfield]. So we laugh about that.

Time Extension: You ultimately left Sega of America in late 1990 and were replaced by Tom Kalinske. Was the difficulty of dealing with Sega of Japan a deciding factor in why you departed the company?

Michael Katz: I got fired by Nakayama because we hadn’t reached in the first nine months of Sega Genesis a million units. The Japanese felt that anybody with Sega in the US should have been able to generate a million units. I had very little contact face to face with the Japanese when I was doing my job because I didn’t want to waste my time reporting what was going on to them. I wanted to try and generate sales and profits. So, I never really played the political game and became personal friends with the guys in Japan.

Nakayama knew Tom Kalinske [my replacement] from the Mattel days. Tom was president of Mattel at one point and he ran into him, he wasn’t happy with the fact that Michael Katz hadn’t generated one million units and so I got fired because of that. I think it was unrealistic for the Japanese to imagine us selling one million units because they knew nothing about how strong Nintendo’s grasp on the category was. Was I happy? Did I feel it was justified? I felt it was not justified, but I didn’t really care that much and I enjoyed starting my own search firm afterward.

What has been aggravating is watching other people taking credit for what we did in that year and a half period, which was basically to establish Sega in the US and have it grow into a very strong number 2.

Time Extension: And just as a final question, what did you decide to do following your time at Sega, and why?

Michael Katz: For about eight years, I had my first executive search firm. That’s what I decided to do about 6-12 months after I left Sega because there was no executive search firm working just in the video game category, and a lot of companies in entertainment media wanted to get into the category.

So, I knew everyone who ran the companies. I knew people who were the hotshots at their positions in the companies. And I said, ‘Hey, I could become the retained search firm’ that represents the video game industry. So, I did that. We had fifty different clients over the years and we placed about 200 people. It was me and basically one or two associates when I needed help. So that’s what I did after I was at Sega. Why did I do it? Because I was tired of bureaucracy, politics, and [working with] foreign companies, and I wanted to do my own thing.

After that, why didn’t I stay in video games? I guess I was tired of video games. I wanted to take some time off. I wanted to do some different things, and the jobs that I might have been interested in either weren’t available or didn’t come to me.