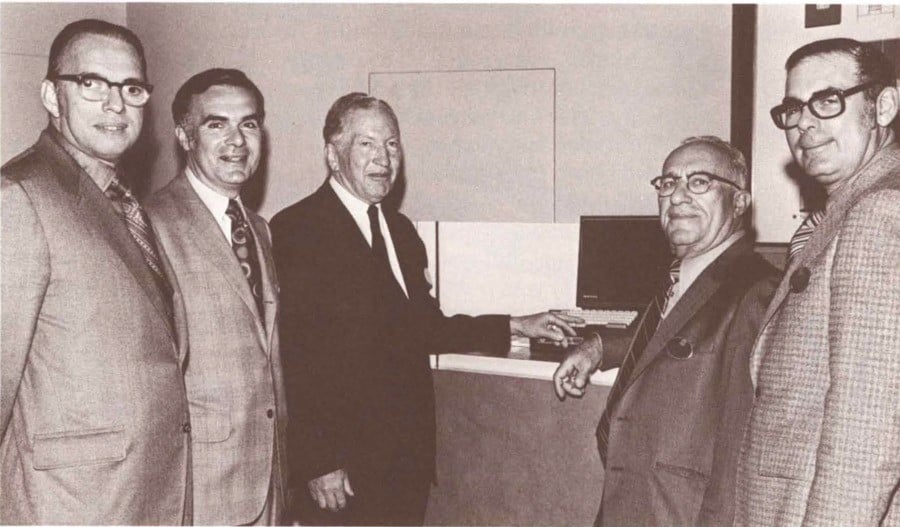

Bert Reiner worked at Coleco from 1969 to 1988, starting as one of its only engineers and gradually rising through the ranks to become the vice president of product development. While at the company, he oversaw the development of the Coleco Telstar line of electronic games, the ColecoVision, and the Cabbage Patch Dolls, giving him a fascinating insight into the history of the company.

Recently, through Coleco's former vice president of marketing Michael Katz (who we've also interviewed in the past), we were able to get in touch with Reiner and asked him a bunch of questions about the company and its various video game products. This turned up a lot of incredible stories that we've personally never heard about before, such as how Nintendo almost ended up marketing the ColecoVision in Japan and why there were so many different versions of the Telstar. You can read a transcript of the entire interview below (edited for clarity and length). Also, as a side note, Reiner has an autobiography called My Journey From Shanghai to Las Vegas available to buy if you want to know more about his life and career.

Time Extension: What was your background prior to joining Coleco? What was your education and where did you grow up?

Bert Reiner: I was born in Germany and because of the war — I was Jewish – we had to escape Germany; we ended up going to Shanghai China. China was the only country in the world that did not require any visas. They had open immigration. So we were able to escape Germany and went to China. Almost at the same time, China was captured by the Japanese and we then lived under Japanese rule. They herded all the Jews into a confined part of the city called a ghetto and I lived in the Shanghai ghetto from 1939 to 1945 until the war ended. We were treated much better by the Japanese than we would have if we stayed in Germany. We were fortunate, so we continued living in China until 1949; after the Communist invasion, we were able to get out. We got our visas to the US. So my parents and I – I have no siblings – so my parents and I then emigrated to the US.

I went to high school and then went to college at Rensselaer, which was one of the top engineering schools. When I graduated, my first job was at Sikorsky. They made helicopters. They’re still around. They’re still the number one helicopter company. But I wasn’t very happy working in the aircraft industry, so I got a job with Dictaphone, which was dictating machines, so that’s how I got into the electronic field. But after two years, I decided to leave that and I went to work in a toy company. That was A.C. Gilbert. A.C. Gilbert was a successful toy company that made primarily boys’ toys. I then became chief engineer and from there I went to Ideal Toys, which in contrast was girls’ toys. So I had a background in toys. So from that point on, I stayed in the toy industry for the rest of my life.

Time Extension: How did you come to join Coleco?

Bert Reiner: I was with another company, Ideal Toys, and they filed for bankruptcy and I had to leave. My wife liked living where we were and didn’t want me to move, so I went to work for Coleco. I wasn’t very happy because the toys that they were involved in, really weren’t toys. It was these vacuum-formed swimming pools. They had bought a swimming pool company and they made above-ground pools. I was the chief engineer. I was in fact the only engineer. That’s when I started.

It was a couple of years later that they bought a toy company called Eagle Toys in Montreal, Canada. They were making vibrator football and hockey games, so I got involved in the toys, and I was a little bit happier doing that. Then eventually they moved more and more into the toys and I was with them for 19 years.

Time Extension: Looking into Coleco's history, I believe it started under Maurice Greenberg. Then I believe Leonard eventually took over from him, with his brother Arnold joining later. When you joined was Arnold already involved in the business?

Bert Reiner: Arnold was a lawyer. He wasn’t involved in the very early days. It was just Leonard and another person; they went to school together. His name was Mel Gershman. He and Leonard were really the two people – his father Maurice wasn’t really involved in the toy business. He was involved in leather goods. But it was basically Leonard and Mel. I was really one of their first employees.

Time Extension: Can you tell us how the Telstar came about? And that range of electronic games?

Bert Reiner: The Atari Pong hit the market and they were quite successful. Leonard Greenberg approached me and said, ‘Let’s get into that business.’ We had no electronic engineers, so I contacted an outside engineering company that was located in Connecticut.

I approached them and I said, ‘What we want to do is compete with Atari. We want to come up with the better game at half the price.’ Pong was about $100 at retail and our target was to come up with something at $50. So I hired this engineering company called Alpex in Danbury, Connecticut (who helped develop the Fairchild Channel F video game) and they started working on the development of a video game. They told me it would be between a year and a half to two years before we could be manufacturing. The reason was we would need to make a custom chip and in order to make it economical, that took a long time. So I said, ‘Who are the chip manufacturers?’ They were all located in the Western part of the United States: Texas had Texas Instruments and San Diego had National Semiconductor. And I said, ‘There’s got to be a company on the East Coast.’ And they said, ‘Well, there was a company called General Instrument, but I’m not sure if that’s the right company to be working with.’ So I said, ‘Let’s go down there and meet with them.’

I went down with the engineers and met with the principals of GI (General Instrument). They were located in Long Island. We presented a potential game to them and told them roughly what we were trying to do. I had to go to the bathroom, and when I came back sitting on the table was a written proposal — very, very detailed — of a phenomenal game, which was everything that we were looking for. They were developing a game in Scotland, and they were way ahead, and they were actually proceeding with the chip. We were quite excited. This game had sound. It was in colour and it had scoring. Things that the Atari didn’t have at the time. We were quite excited. This would give us the game we wanted and we could get it in like six months instead of two years. We ended up placing a contract with them for 950,000 chips at $5 a chip and an exclusive contract that agreed they wouldn’t sell these chips to anyone else. That was how we first got started in the video game business.

Time Extension: Why was the decision made to produce so many different variants of the Telstar? I’ve seen newspaper reports say that there were 8 commissioned fairly early on in 1977, but online it seems to say that there were 14 total.

Bert Reiner: Well, what happened was, as I said, we had the exclusivity for the chip and we were enormously successful with the Telstar. We were selling them at $49.95 retail and we beat the hell out of Atari Pong. But what happened was as soon as those six months were over, our exclusivity ran out and General Instrument started shipping those same chips to virtually everybody. The following CES Show — that’s the Consumer Electronics Show here in Las Vegas – I counted 28 manufacturers most of them from China selling essentially the same game. The housing looked different, and the controllers were different, but the actual game on the TV screen was the same as ours because they all used the GI chip. So we recognized that we needed to expand that business and we started developing other games that were all based on the same GI chip. We had different games that we developed; there was a tank game. We really expanded.

Time Extension: There were a lot of reports at the time that the Telstar missed an important Christmas deadline in, I believe, 1977. As a result, in 1978, Coleco was left with a lot of stock that it needed to sell at a lower price. I found a PDF of the 1981 company history, and in there, Coleco refers to it as one of the only times that its future was in jeopardy. What were your memories of that event?

Bert Reiner: What I realized when we first started manufacturing, which was in upstate New York at our factories, was that in order to be really economical, we needed to get the manufacturing done overseas. I went to Hong Kong and Taiwan — at that time China was not open to us. I visited 18 factories and found a company called Zeny that we finally ended up working with in Southern Taiwan. They did the manufacturing of the PC boards and they were doing the Telstar for us. Just the PC Board. The rest of the manufacturing – the assembly of the video game itself – was done in upstate New York at our factory.

Later that year, there was a strike at the dockyards in California, in Long Beach, and we had a lot of merchandise sitting there around Christmas time. That’s what caused the problem. We couldn’t for a short time produce it and we didn’t have the merchandise available until after Christmas.

Time Extension: I was going to mention the ColecoVision following that, but I guess before the company came out with the ColecoVision it also shifted toward making handheld electronic toys. I’m wondering, what caused that kind of switch? Was that just the market changing at the time and that was the next big thing on the ascendance?

Bert Reiner: We started to expand our business. I hired a number of electronic engineers including Eric Bromley (from Bally Games) and Mark Yoseloff, PhD (who later became Sr VP of Coleco) and that business started to grow. We did develop some electronic toys but basically, we were interested in video games and then we came up with a much superior game which was the ColecoVision. The handheld business didn’t really come until after. Our concentration was really on ColecoVision. So it went from Telstar to that. So that was what we were concentrating on. We had the Atari 2600, and we also had Mattel’s Intellivision, but between the three of us, we were really the best game out there: the ColecoVision.

Time Extension: How hard was it for Coleco to get back into business after what had happened with Telstar and the shipping problems in '78?

Bert Reiner: We really didn’t have any problems. As I said, we increased our engineering staff. We hired some pretty bright engineers, who were developing this new game, and we were very, very successful at doing that. So I wouldn’t say we had any problems. It was just a natural transition to go from the Telstar, which even though it was better than Pong was still very limited. It was basically a tennis game and nothing more than that. So we really needed to come up with something considerably better and that was when the ColecoVision came about.

Time Extension: Do you remember much about how Coleco and Nintendo came to know each other as companies? I’ve read an account from Eric Bromley who worked at Coleco that he actually travelled over to Nintendo to license Donkey Kong. I’m wondering, was that the first instance of Nintendo and Coleco crossing paths? Or was your own trip to meet Nintendo before that?

Bert Reiner: No, my trip was after that. Eric Bromley, who worked for me, went to Japan and looked at several games that they had. At that time, Nintendo was basically making playing cards. They were the largest playing card company in the world. The cards that you play in poker and whatnot. They also made large, stand-up arcade games. They had a number of games that were quite good, one of which was the Donkey Kong. So Eric went to Japan to meet with Nintendo and he struck a deal exclusively for us and we got the rights for the Donkey Kong. We included that in the ColecoVision. So every ColecoVision that was sold included a Donkey Kong cartridge. It was truly a good game so that helped the sale of ColecoVision.

I went to Japan later, after we had already established a relationship with Nintendo and I went to Japan with Leonard Greenberg and met with Yamauchi, who was then the president of Nintendo. They were interested in buying the ColecoVision for the Japanese market and we were obviously interested in selling it to them.

Time Extension: In regard to that conversation, what was the point where those negotiations broke down?

Bert Reiner: What happened was we went to Japan and we were willing to sell the game [console] to them at 10% below our wholesale price. So Toys ‘R Us we’ll just say could buy it for $10, they could buy it for $9. Nintendo, on the other hand, wanted to do their own deal. They wanted to do their own manufacturing, their own marketing, essentially do everything, and give us 10% of their selling price, which obviously would be lower than our price. I thought it was a good deal because we would have to do absolutely nothing and we would get 10% of every unit that was sold in Japan. We couldn’t strike a deal. We spent several hours – Leonard Greenberg and Yamauchi through a translator of course – and finally we decided to walk out and no deal was made. Yamauchi said – I spoke a little bit of Japanese – he said that they would develop their own game [console]. Leonard Greenberg laughed. The rest is history. They, of course, got into the market and we really lost out.

Time Extension: Do you remember your reaction to seeing Donkey Kong for the first time? Because from what I’ve heard Eric paid a lot more than what was the typical licensing fee to license that game. So what I’m wondering is, was there any skepticism about that game at the time or did people just see it and know it was going to be an amazing pack-in title?

Bert Reiner: As I said, I wasn’t directly involved in that, but the feeling was we spent too much money on it, on this crazy game. But when you actually started playing with it, everybody liked it. It was a huge success and it was really the Donkey Kong cartridge that made ColecoVision a great success. We had great software in the game. The chips that we used, we had sound, we had RAM built into the computer, and the Donkey Kong really showed off the possibility of what the ColecoVision could do. I think that turned out to be a great decision and that was clearly Eric Bromley’s.

Time Extension: I think when a lot of people look back on console gaming in the early '80s, they think of Atari, but it seems ColecoVision had this amazing impact and influence on how the industry evolved. Do you have any thoughts on why the ColecoVision isn’t more appreciated today?

Bert Reiner: I don’t know. I think it’s a good point you’re making. ColecoVision became very, very successful in the US and was also sold in Europe. It did not sell in the Far East. I don’t know. Nintendo took over the market and they were certainly more successful. I don’t really have an explanation as to why.

Time Extension: Something I mentioned prior to the interview is that I found a couple of newspaper articles about Sega also potentially distributing the ColecoVision in Japan. At the time, this came after news that Coleco had licensed a number of Sega-Gremlin games like Zaxxon. Do you have any memory of that?

Bert Reiner: I really wasn’t that involved. What happened was I was vice president of product development, but then as we started to grow, we broke off the department and Eric Bromley headed that other department. They were responsible for all the software of the video games and I was responsible for the hardware. He was involved in his department in securing other games like Zaxxon from Sega, and there were other Japanese companies that were also supplying software to us. So we had quite a library of cartridges that went with the ColecoVision. I wasn’t personally involved in that.

Time Extension: In terms of hardware, the ColecoVision was obviously modular, so you could attach these separate game modules and new controllers to it. It was briefly mentioned in a news article from the Sacramento Bee that there was an Intellivision Game Module planned. I know that Coleco did one for Atari where you could play Atari 2600 games. Was it ever planned for Coleco to do an Intellivision Game Module to let you play Intellivision games on the ColecoVision?

Bert Reiner: I don’t think we did that. I do remember we did cartridges that allowed you to play the Atari cartridges, but we did not do that for the Intellivision. They were really not that successful. So I don’t remember doing anything with the Intellivision that we did for the Atari.

Time Extension: When Coleco launched the Atari adapter to play Atari games on the Colecovision, both Atari and Coleco ended up threatening each other with lawsuits. Atari charged Coleco with patent infringement and unfair competition whereas Coleco responded and charged Atari with violation of anti-trust law and claimed that it didn’t infringe any of Atari's patents. What do you remember about that?

Bert Reiner: I really wasn’t involved in that, so I really can’t make any comment. I don’t recall very much about that.

Time Extension: Do you have any memories of the Atari Gemini system that Coleco released? That was mentioned briefly in a New York Times article after Coleco and Atari reached an agreement. It was made to be an Atari clone system and was developed by Coleco.

Bert Reiner: Yeah, that was not very successful. We didn’t manufacture that for very long. We did come up with a number of different iterations. Different games, both hardware and software. But we should have stuck with the ColecoVision, but we wanted to expand and not all of them were nearly as good.

Time Extension: Another unreleased module I found that seemed like it had a bit more work done to it was the Super Game Module. Newspapers were saying at the time it was coming in the Fall of 1983 and that it was going to be compatible with thin magnetic tapes rather than a solid-state chip. I believe the purpose of that was to produce even better graphics. What are your memories of the Super Game Module and why that didn’t come out?

Bert Reiner: Well, as we started to expand with more and more cartridges in the family of games, we also started developing a computer. It was called the Adam computer, which had magnetic cartridges and allowed it to play the ColecoVision games as well as being a computer. That was the intention. The company expanded its development. We had well over 100 engineers in my department and Eric Bromley’s and they were basically concentrating on the Adam computer as being able to go into two markets: expand the video game market and go into the computer business.

The Adam computer was a very complete, self-sustained product, where we had the computer, the keyboard, and it even had a printer. The power supply for the Adam computer was in the printer. Together all you needed was a screen, which was basically a television so that was the only thing that was not included. All you needed to do was plug that into your monitor. That retailed for about $750. That was considerably cheaper than any other computer at the time. The closest computer was like a TI, which was $2000 in comparison to ours.

Unfortunately, we had a lot of problems with that. As fast as we were shipping the product, they were coming back. So that was not very successful.

Time Extension: You mentioned problems. Two negatives that frequently came up looking at the reviews of the Coleco Adam at the time were that the power supply was on the printer and there were some people who said that the machine generated a strong magnetic field that could erase data packs placed near the data drive. Do you remember any of these issues and how they were received within Coleco?

Bert Reiner: It's true. We did have some problems regarding the magnetics but the real big problem was the power supply – the printer – which was actually partially manufactured in Ireland. It wasn’t the manufacturing; it was the design. I personally wasn’t involved in it unfortunately and we had enormous problems. But mostly the problems originated with the power supply.

Time Extension: The perception regarding the 1983 North American video game crash is that everybody suffered, but it seems like from the newspaper articles I was reading prior to this interview that many people thought of Coleco as an outlier in that because the ColecoVision sales in the first quarter of 1983 were very good. I’m wondering, was that perception in the company at the time? That things were going quite well even though there was this specter of a crash?

Bert Reiner: We really stood out with the success of that. 1983 was also when we came out with the Adam computer. The stock went up to $50 from $3 a share. Coleco was on top of the world. But the problems we had with the printer were the downfall of the Adam computer and the ColecoVision as well.

Time Extension: As a final question, I'm just wondering, how much do you think the success of the Cabbage Patch Dolls was to blame for Coleco staging a retreat from video games in 1985? It was kind of shocking to discover but the LA Times reported that in 1984 $500 million of the estimated $800 million revenue that Coleco generated was all down to Cabbage Patch Dolls.

Bert Reiner: What happened was we broke up the product development group as I said. Fortunately, I wasn’t involved in the Adam computer. That was a huge failure as I said. I was responsible for the development of the Cabbage Patch Dolls. I had previously worked for Ideal Toys, which was a doll company. I was not only the head of engineering but I was literally the only person that had any experience in dolls. I had worked with two manufacturers in China — actually in Hong Kong, called Kader and Perfecta. I went to China with the idea of sourcing probably one of those two manufacturers. We were originally planning to make 1 million dolls that year – 1983. We actually shipped 3.3 million.

So when I approached the manufacturers – both of them – the idea of making every doll different, they laughed at me. They said that’s impossible. For all the years that they were in the toy business, the idea was to make them all alike. Then here I come along and do just the opposite. I went back to my hotel that night and I thought, ‘How am I going to go back to Connecticut and tell these people that we can’t do Cabbage Patch Dolls? That it is impossible.’

I sat there in the hotel room and I came up with the idea of a matrix of how we could make them all different. So, if you picture you have to paint a doll with let’s say blue eyes and then do the next doll with brown eyes, you can’t change the paint and the paint mask and the paintbrush; it just wouldn’t be practical. So the Matrix that I developed was we had a line of six girls because we had six different heads – these were vinyl heads; we had six different molds. So we had six girls painted with all blue eyes. Then we had another line of six girls with brown eyes. And then another line with green eyes. So here you had a matrix of six heads times six paint colours, so we now had 36. We did the same thing with the hairstyles and the hair colours. I did this all in the hotel room, went back to the manufacturers the next day, and said, ‘This is the way you have to set up the factory’ and that’s what we did. We ended up producing, as I said, 3.3 million dolls that year.

The Cabbage Patch Dolls really saved the company because we had such a serious problem with the Adam computer. Fortunately, the Cabbage Patch Dolls were the same year and that saved the company.