On February 25, 2025, it was announced that the Washington-based developer Monolith Productions would be closing its doors for good, causing a mass outpouring of grief from all corners of the games industry.

Since its formation back in 1994, the developer had built up a large and loyal following in the gaming community, thanks to its work on licensed games like Middle Earth: The Shadow of Mordor, Tron 2.0, and Alien Versus Predator 2, as well as classic first-person shooters like Blood, The Operative: No One Lives Forever, and F.E.A.R.

However, this would all come to an end earlier this year, when its parent company Warner Bros. Games cancelled the studio's long-in-development Wonder Woman project and shuttered the studio in a restructuring of its business.

In the aftermath, many former Monolith Productions members took to social media to express their thoughts on the decision, with one of the company's six co-founders Toby Gladwell posting on LinkedIn that he was "gutted" to see the place he helped start become "yet [...] another story in the sad affair that is the games industry." As a result, we wanted to do something to commemorate Monolith's tremendous legacy, so we reached out to the co-founder (who worked at the company from 1994-2005), to reflect on some of his favourite memories of the studio and what he believed made the developer so beloved. Below is our conversation (slightly edited and condensed for length and clarity):

Time Extension: To start it'd be interesting to go back to the very beginning. How did Monolith Productions start?

Gladwell: So, I'm originally from the UK and in the late 80s, the demo scene was kicking off and graphics programming was a really big thing. Back then it was all about using assembler and writing code that ran super, super fast, and creating very rudimentary 3D graphics. I'd kind of been doing that for a couple of years in the UK and then I moved out to the Seattle area, in '93, and I got an interview at [the educational software developer] Edmark.

At that point, I was aware of the games industry and it had already kind of started a little bit in Seattle, with studios like Sierra Online and Zombie. And I think probably one of my best memories from that day [was meeting] Jason Hall (another one of Monolith's co-founders, alongside Brian Goble, Brian Bouwman, Garrett Price, Paul Renault, and Brian Waite). I had been playing Wolfenstein 3D back in the UK maybe six months earlier and I was going upstairs to meet one of the engineers at Edmark and I walked past this guy on the stairs. He's tall, he's bald and he's wearing a Wolfenstein 3D t-shirt and I thought to myself, 'Oh this would be a cool place to work'.

So I got the job there and then very quickly, we connected because Jason was into music and the demo scene. And then, I met Brian Goble and Bryan Bouwman, who were also very much into gaming and whatnot. Anyway, at that point, Doom had just come out. And it's got to be within the first week I was there, we were doing LAN parties in the evening, playing Doom. Then Doom 2 came out and it was just amazing. It was graphically incredible and it had solved some really challenging problems in a really, really cool way.I think Doom was kind of not necessarily where Monolith was born per se, but because of that, we realized we all had a very similar attitude. We loved games, and we felt we needed to go and build these kinds of games that were definitely inspired by Doom.

There's this book, Steal Like an Artist, and it says there are not really any original works per se, and you want to stand on the shoulders of giants. Back then we were in our 20s so we had a lot of ego, but not necessarily hubris, which are two different things, right? And we really, really, really cared about these games that we were going to build. We didn't know exactly what they were yet. We didn't have product managers and a lot of the structure of the industry hadn't even formed back then. But we thought very strongly a lot about the products that we thought we were going to build.

Time Extension: It was around that time that you created the Monolith CD, right?

Gladwell: Yeah, at Edmark, we started experimenting. We created some demos. Jason was working on music, and then we had this fusion between us of small software demos and created the Monolith CD, which, at the time, was pretty impressive. I forget how many we stamped, but we burnt like a couple of hundred maybe, and we said 'We'll distribute these out to publishers to put ourselves out there'. And that's when we had some introductions to Microsoft and the DirectX team.

So I look at Edmark now as we played a lot, we talked a lot, we dreamed a lot, and then we all came together and we realized, 'Hey, we should go do something about this. We could keep working here on stuff but there's an opportunity here for us to get together and go do some amazing things'.

Time Extension: Once you formed Monolith Productions, what was the next move? What came first? The Windows 95 sampler CDs or the idea to build a 2D platformer (which eventually became Claw)?

Gladwell: Brian Goble had been working on this engine: a Windows Animation Package. And there was a game that he had created that was basically a side-scroller. So we had some side-scroller fans inside the studio. But the first project we landed with Microsoft was to create the Windows 95 sampler CD, which was kind of a showcase for Windows 95 games. It was in DirectX as well, which was just this huge jump over what was previously available.

So we had talked about sidescrollers, and there was a game called Jazz Jackrabbit that had just come out at Epic, which was a cool game and had an awesome soundtrack. And I think we all looked at the sidescroller kind of game as something that we could definitely do. But Claw really emerged after we had completed the first project with Microsoft. At that point, we were all working on-site at Microsoft. That would have been the beginning of 95. Then we got our first kind of office building and that's when we started working on Claw amongst other things.

We had one team focused on Claw and I myself was focused more on the 3D engine side of things. So I was working on DirectEngine, which was the original name before LithTech arrived. But yeah, Claw was a pretty big effort and we were cutting our teeth as a team on that, figuring out structure as we went. We'd had investment into Monolith from a company based out of Japan, called Takarajimasha. and that kind of got us some runway. Claw, I'm trying to remember, was maybe 97?

Time Extension: Yeah, it came out in 97. I guess, this is what is so interesting to us as outsiders. Claw came out the very same year as the FPS Blood — another Monolith project — which were obviously totally different tones and genres from one another. From what we've heard, how this happened is Monolith merged with another Washington-based studio, called Q Studios, who were already working on the game.

Gladwell: Yeah, back then, when we looked at games, we were looking at side scrollers, but we were also absolutely looking at first-person shooters too. That was really the core driver at Monolith. So we felt that that would be a good acquisition for us. It was a great team of folks and we actually already kind of knew them. Nick Newhart, their lead designer and one of the founders of Q Studios, had actually left the position that I ended up doing at Edmark, [which meant] we actually had some ties to Q Studios. I guess that deal would have been in 96/97.

Time Extension: Following that, the studio went on to release Get Medieval in 1998, which was a Gauntlet-style hack-and-slash game that featured a pretty ridiculous sense of humour compared to other fantasy games of the time. The intro to that game, in particular, is crazy. Humour was something that obviously became a key trait of a lot of Monolith's games. Do you remember anything about that project and how that kind of came about?

Gladwell: I didn't work on Get Medieval directly. But we loved Gauntlet, right? Like, it was a remake of Gauntlet. And it was something that we felt we could build pretty quickly as well. We were looking at like, what is a smaller game? I think Claw took a lot longer and a lot more money than we had previously planned for, so that was the thinking there.

I'd like to touch upon your point about humor, though, because that's one of the magic things I think we shared among us. We loved to laugh together as a group. From an outside perspective, maybe we seemed a little bit too silly or like we were acting like kidults. But that was critical in some ways to our success because what it meant was that it was a creative atmosphere. It instilled in the culture this idea of having fun and enjoying things, and that maybe we shouldn't take ourselves too seriously either. That allowed us to explore different ideas. And then, of course, that culture made it into some of the games for sure.

You can see that in some of the later titles like No One Lives Forever. And we also did a small RTS game called Grunts, and the humour is there for sure.

Time Extension: Yeah, I would add Shogo Mobile Armour Division to that too. That was another early Monolith game that a lot of people have a fondness for and is packed with jokes. I remember there was this memorable quest in which you have to get this old woman to open up a gate and she asks you to find her cat. You can just blast her away and open the gate yourself, but if not, there is this weird quest you go on where you have to get a cat toy and go through a bunch of increasingly ridiculous steps. It's things like that that are just bizarre and you can tell that it's very much made by a group of people rather than some overly corporate culture dictating what you could or couldn't do.

Gladwell: To speak to that point, the culture that we had was we still wanted to execute and move things along, but there were no [walls in place]. If a designer came in to sit down with an engineer or vice versa, we just mingled. You see a lot of siloing in a lot of the larger game studios now and I think that calms down game development significantly.

I wouldn't even say we actively [avoided that], it was just part of the culture we developed. You would get to listen to everyone's opinions. How I would describe it is anyone could come along with an idea, but you would have to be prepared to put the idea out on a table and have everybody get a 50-caliber Browning machine gun and go crazy on it. If the idea is still standing up afterward, then it's probably a pretty good idea.

It was definitely a very open culture, which I think contributed to a lot of the maybe more humorous elements and the fun in the games that we created.

Time Extension: Shogo was the first Lithtech engine project too, right? I remember coming across this promo video on YouTube, showcasing the games you were making for the engine. It mentioned Shogo Mobile Armour Division (but it was called something like Riot at the time), Blood 2, and then it also mentioned two more games that never happened: Claws 2 and a medieval-style game called Draedon.

Gladwell: Oh gosh! Now I have to go back. So it was Draedon or Draven. Yeah, I don't remember exactly what happened with Claw 3D. But we were working on an internal demo of Draedon/Draven. And I don't remember exactly what happened there, but wedecided not to move forward with that...

Time Extension: I think the designer/programmer Kevin Lambert said once in a blog that Monolith was just putting together a lot of different things to see what would kind of go ahead.

Gladwell: Yeah, it's funny. I'm actually going to be catching up with him soon. I'll have to ask him about that.

Time Extension: It would be cool to hear what he remembers. So Shogo was the first 3D project or at least it was the first one that came out with the LithTech engine. Do you remember how long that project was in development? You mentioned working on a 3D engine as soon as the studio was pretty much formed. We're wondering, was that something that was in development pretty much from the start?

Gladwell: It was, yeah. I mean, it was a case of we're building the technology. It's the classic, you're building the aircraft as you're flying it, which is not a great way to go about things, but it's what we were doing at the time. Especially because you could see iD clearly had a really great 3D engine that they were using for Quake, and Unreal was in production at Epic and on the way. So we definitely wanted to build out our technology as well. But in doing so, there were a lot of challenges and hurdles.

To give an example, I think Blood II: The Chosen, suffered in the same way that I think a lot of the early kind of 3D games did, in that it was actually pretty hard to achieve the same level of visual quality or the same look we could get with a 2D sprite, raycasting engine, like the one Doom, Blood, Hexen, Heretic, and all those games used. I think Blood 2 kind of suffered from that. Because there were a lot of challenges in building 3D technology that were computationally expensive at the time.

Those mostly came down to 'We've got a way to represent our level, but it's not fast enough. We've got to go back and we've got to optimize.' So there was a lot of time invested in that in those early days of LithTech. And that, of course, pushes release dates out. I think we would have liked to have shipped Blood II quickly and moved on. But that did end up taking longer than I think any of us had expected. And we were growing too, right? We wanted to grow. We wanted to expand. But again, I think probably because we were all a little younger, we didn't realize you need to control that growth really carefully. There was quite a bit of expansion that we went through that was good in some ways and had a negative impact in other ways as well.

Time Extension: Is that in relation to the publishing side of things? It seemed like in the late 90s, Monolith temporarily made the move to start publishing other people's games too, like the Rage of Mages series and Septerra.

Gladwell: Yeah, I think again hindsight's 20-20. Publishing for us was something that we were really excited about, but it also, you know, it was a huge, huge distraction. And, I think at our core, Monolith was always about let's make great fucking games — incredible games that people want to play — and let's listen to the community and build games for the gamers.

Adding publishing was another layer on top of that, but it also can also create conflict too, because the publisher wants to ship quickly. The publisher wants to limit costs. The publisher is very concerned about time. And so, from a developer standpoint, you want to be creative. That requires time, you want to get things right. There's this sort of push-pull there that trying to do publishing introduced and that was on our internal titles too.

Time Extension: In the late 90s, things obviously got difficult for Monolith as a result of expanding too quickly and you eventually had to let some people go due to issues with spreading yourselves too thin. This period, however, was then followed by this amazing time when Monolith started to hit a creative stride, bringing together all these different elements it was good at: humour, first-person gameplay, and selecting interesting influences from film and literature to use as a jumping-off point.

Gladwell: Yeah, I agree. Again, I look back on it and it's easy to see the missteps, but at the time we felt they were the right steps. And the learning from that period of publishing was to focus on what we'd originally wanted to do, which was first-person shooters. And so, you're right, if you look at that period, the focus then became, 'Okay, well Shogo was awesome, let's go make No One Lives Forever, No One Lives Forever 2, and Aliens versus Predator 2' —

Time Extension: — And Tron 2.

Gladwell: I was going to say, I have a Tron 2 copy in my office somewhere knocking around. And I think this is important as well. We took those IPs — Aliens, Predator, and Tron — and we made them our own. We put our Monolith kind of spin on it. We knew we didn't want to just make games that matched the films.

We didn't want to go down that path. Tron 2.0, in particular, was amazing, because, you know, at one point Syd Mead was working with us to come up with the new lifecycle designs. So here we are as the absolute Tron fanboys when we were growing up, and now we were absolutely steeped in it. And I think that melding of IP or genre with our own flavor of development worked so well for that chain of titles, starting with Shogo and No One Lives Forever, then Tron, No One Lives Forever 2, and AVP 2. Obviously F.E.A.R came later — I had actually moved on at that point — but you can kind of see that progression there too.

Time Extension: Yeah, it definitely seemed like there started to be a core identity to the company's games. Do you remember what the considerations were when you guys were discussing what projects to take on next?

Gladwell: At the time, there were a few things. We needed to be able to get behind it. And that meant it had to be something that we all saw as 'This is a cool thing to work on'. We had to be psyched or jazzed about it, right? Like if something came in and we were like, 'Yeah, that doesn't sound very interesting or cool', we'd be like, 'Yeah, we're going to reject that.' That was one of the first filters.

Again, for a lot of us, growing up in the 80s, we loved Tron, science fiction, Blade Runner, and all these different influences. So we were always like, 'Can we take this thing — whatever it is — and find a way of making something really cool from this?' And I think that's really how we started. Like, I don't think we were a place that did a load of user research, but we did sort of rely a lot on what we saw from the fans of those IPs. How do people talk about the movie Aliens, right? And I think that's really what gave us the bellwethers for different IPs that we were looking at. And, from one game to the next, I think that really held true.

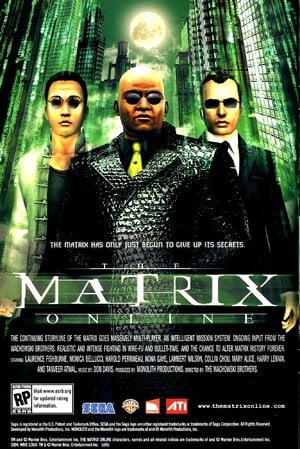

To give an example, my last project at Monolith was actually The Matrix Online. We had all seen The Matrix when it first came out in 99, and, as a company, everyone was like, 'Oh my god, this is us. We are Neo. We are Morpheus.' That was the ethos around how we consumed IP. I look back on it now and I think we were all very, very passionate, very engaged people, who were super geeky. We loved to geek out at all levels of the company as well. That was the culture.

Time Extension: You left the company in 2005. Do you have any thoughts on the company's output after you left? Could you still see that same level of passion and creativity?

Gladwell: I stayed in touch with a lot of the old crew, so I never felt like I was a million miles away, especially just being in here in Seattle — the game community here is still so small. But playing the games, I felt that same level of creativity there with everything that Monolith did.

Even Gotham Imposters — that released in 2012 — I remember it not being particularly well received at the time, but I recall playing it and going 'This is Monolith taking a bet on something', right? Not every single title is going to be a hit. You've got to take some chances. Even there I still felt like that's Monolith doing its thing. And then Shadow of Mordor came out and again here's just this wonderful storytelling and absolutely superlative gameplay. Again, I wasn't part of that, but I was so happy to see Monolith release that title. You could still see it was a project that was staying true to the roots of the business that was allowing them to take chances and flourish.

Time Extension: Obviously, we couldn't speak to you without getting your thoughts on the company's recent closure. To us, it just seemed so sudden and so sad to see the Monolith come to an end in that way. It would be interesting to hear your own thoughts, especially as someone who had such a large connection to the company in the past.

Gladwell: From the outpouring of communication from folks both to the people at Monolith let go and also to the wider Monolith family, you can clearly tell there's a legacy there. And to have been a part of that is humbling.

It was hard work and effort, and none of us could have [imagined that] 31 years down the road. But it left a legacy and I think, for those people that were involved with Monolith, it probably encouraged a state of thinking of, 'Hey, you can push yourself a little further and you can work with a team and create something cooler and bigger than maybe you thought you could.' We held ourselves to high standards and I want to think that because of that, part of the legacy of Monolith will live on through the games that we produced over the years.

I've been away from Monolith for 20 years now, but my heart is still very much part of that place. And just the outpouring of communication afterward, it felt like grieving a significant loss, and I had people reach out and say the same thing.

As for the rest of the industry, I think we've gotten ourselves to a place where we've put monetary reward and pleasing shareholders over the act of making really truly great games. And I think the marketplace has become a little bit saturated with 'meh'.

I think you've got a few studios that are really killing it, like Larian Studios. They've done an absolutely superb job of maintaining their identity and culture over a long period of time, but the games industry is in a pretty tragic place right now.

So I hope that there are younger indie studios that start popping up that are full of these people who want to work together and build great things and try and capture some of that energy and excitement again. Because that's ultimately why we do this.

I'm an old grey beard now, but I'd like to put myself in there as well.

Time Extension: Yeah, I'm just hoping that the people who worked at Monolith end up landing on their feet and we get to see more of their creative voice in the future because I think a lot of people were really excited to see what they were working on with Wonder Woman and obviously now it's just like one of those things in the industry where it'll be like several years before anything does come out about that project to sort of give us a proper insight into what they had planned.

Gladwell: It is definitely a shame. I know Monolith would have released something great. And it's a huge shame that we didn't get to see what the team was working on.

Time Extension: Thanks for your time Toby! It was a pleasure chatting with you.