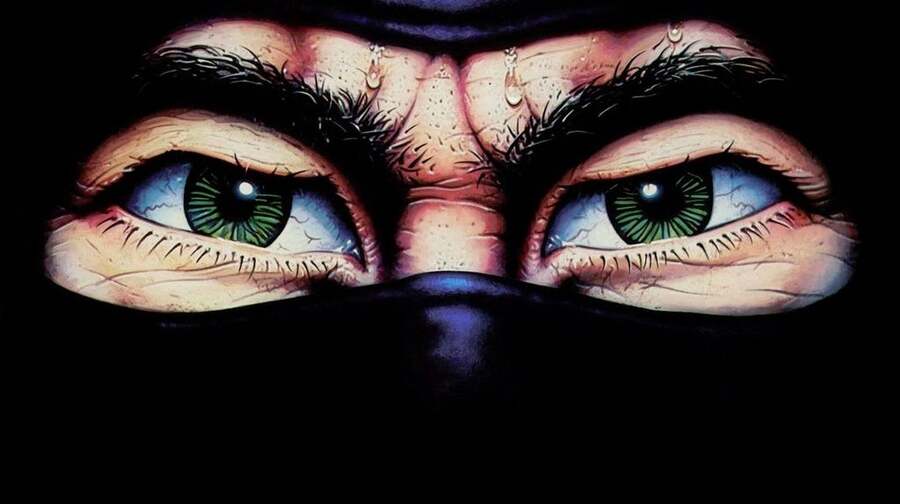

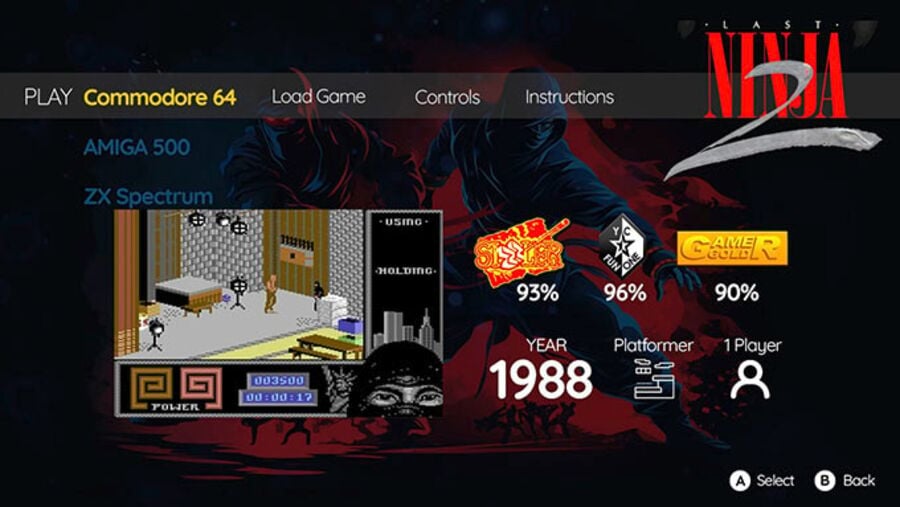

Last month, the British publisher System 3 announced that it would be bringing back The Last Ninja games in the form of a new collection for Nintendo Switch, PS4, PS5, Xbox One, and PC, which would be crowdfunded through Kickstarter.

This collection, which was described in the campaign as "a tribute to the golden era of computer gaming", is scheduled to contain various ports of the Last Ninja trilogy (and Ninja Remix) as well as three additional System 3 titles, including International Karate, IK+, and Bangkok Knights. This means altogether, players will have access to 7 classic titles inside the one handy collection, giving them an easy way to get acquainted or reacquainted with the martial arts games that originally put System 3 on the map.

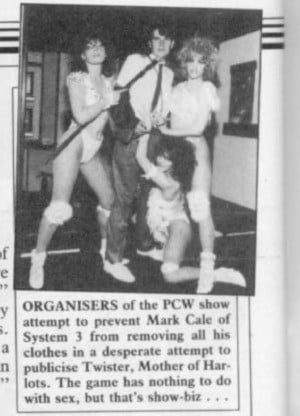

Already the campaign seems to be doing extraordinarily well on Kickstarter, managing to hit its initial goal of £10,000 within just 40 minutes. So we thought it might be a good idea to catch up with Mark Cale, the co-founder and CEO of System 3, to learn more about the origins of some of the titles that are included in the collection and what led to him starting this current campaign. In the process, Cale told us a few interesting stories, such as why he considers System 3's first game, Colony 7, a failure; how a dodgy dance routine at a Personal Computer World event in 1985 helped win the developer/publisher a contract with Activision; and the tale of System 3's Killer Instinct rival that was never released.

You can find our conversation with Cale below (edited for length and clarity):

Time Extension: Nice to meet you, Mark. First of all, it would be great for us to go back to the origins of System 3. You've previously stated in interviews that you became a freelance photographer after finishing school and that you did some work for Atari UK. I'm wondering how did you go from that to 'I want to start my own video game company'?

Cale: Basically when I left school, I became a photographer's assistant. I worked in Covent Garden for a photographer called John Rawlings (author's note: not to be confused with the Condé Nast Publications photographer of the same name who died in 1970). And, in the summer, I was the second assistant for a photographer called Norman Parkinson, who photographed all the Royals, and who was a very famous fashion photographer.

Anyway, John knew my passion for games and told me there was no money in photography anymore and maybe you want to pursue another direction. So, you know, something that was on my mind at the time, and I had met quite a lot of people within Atari UK.

Atari started off working with a distributor. I think it was Ingersoll Electronics. But then it set up its own corporation, and by chance, it set up its head office in Alperton which is quite close to where I lived in North London. And so I sold them on the idea that I could take some photographs and screenshots of games and computers and things like that. From there, I got to know a few people there and just criticized their games on the 2600 and the 800. And, eventually, they just said, 'Why don't you just set up your own video games company?' So I did.

Effectively, without that input with Atari and that connection there, I don't think it would have happened. I would have stayed in the photography world.

Time Extension: Following on from that moment, how did you go about establishing System 3? In the past, we've heard that there were two other co-founders who didn't end up sticking around. Are we correct?

Cale: No. Originally, there were three of us. Emerson Best, Michael Koo, and myself. Michael was doing a computer studies [course] at college called System Studies and because there were three of us and we wanted to make video games, that's why the company became System 3.

Michael never went through with setting the company up. Emerson did set the company up with me. He was with me for a number of years, and then I think around 1985, I bought him out and ended up owning the whole company. So I took on the responsibility myself.

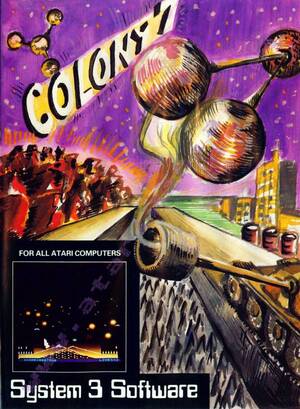

Time Extension: In other interviews, we've heard you mention before that you think your first game (Colony 7 for the Atari 8-bits) wasn't a particularly great product. We're wondering - what went wrong with that initial release? Was it just a matter of finding your feet?

Cale: It was our first product. So we had that. Then we had Lazer Cycle on the BBC and Death Star Interceptor on the Commodore 64. And different people were programming different elements of it. Colony 7 was done in Graphics 9 mode. There was a chip called the GTIA chip that had this sort of shading which was beautiful at that time.

You look at it now and you're like, 'I don't know what you're talking about', but back then you're looking at all those colors that blend into different grays or greens or reds and that was Graphics 9. And so the game was written for that. That was the idea.

It was based on a game that I knew from a company called Sirius called Bandits on the 400 and 800 and Commodore 64 computers. So we thought, 'I'd like to do something like that, thank you.' But there was no money, no budget, and it was just our first attempt at things.

Time Extension: And how long after Colony 7 did you get in touch with LT Software (who developed International Karate and Twister for the ZX Spectrum)? You ended up getting in touch with them through the Stampers' agent, right?

Cale: Yeah, it was through the Stampers' agent. So, the Stampers' agent introduced us to LT Software, but he also introduced us to David Bishop and his partner, who introduced me to Robert Stein, and that was at CES in 1985.

We met LT Software through him. I can't remember the agent's name, but basically, LT Software started to work on International Karate and also Twister. Jon Hare and Chris [Yates] from Sensible Software worked on Twister and Jon was doing the graphics for International Karate [for the Commodore 64].

At this stage, I was trying to do a deal with Activision to be our global publisher and someone suggested I should contact Archer MacLean because he's a bloody good programmer. He had just finished Dropzone. And I reached out to Archer and got him on board. We drove up to LT Software and saw the code, which he said was terrible. He rewrote the code and Jon Hare gave him the basic graphics.

Then, in the meantime, we were working with the Hungarians [on the Spectrum version], which was through Andromeda (Andromeda was a company that Robert Stein owned). LT Software did end up finishing International Karate [for the Spectrum], but it wasn't the best version.

Time Extension: Of course, we have to ask about PCW (Personal Computer World) 1985. How important was that event in terms of building publicity around System 3 and getting the company on the map? If we're right, that event took place in September 1985.

Cale: It did indeed. At that particular point, we'd met Robert in 1985 at CES in Las Vegas. LT software was doing International Karate [for the Spectrum]. We had done a deal with Archer in, I think, June 1985, for the Commodore 64 version. We had Twister, which was going pretty well because Jon and Chris were working on that. But the PCW show came about and we effectively had nothing to show.

My mum had put her trust in me and mortgaged her house up to the hilt for us to do this big show. And I started to have a lot of sleepless nights because I thought, 'Christ, we've got no product. Nothing to show. How are we gonna get distribution deals to sell our products worldwide?' And it was just before this point that Emerson left because he didn't want to put up the same as my mum via his parents and that's why we negotiated a goodbye between ourselves in an amicable way. So it dawned on me, 'Let's make this into a show. Let's just be very outrageous.'

So I thought, 'I tell you what we'll do. We'll set up a stand that's two hexagonal shapes together. One hexagonal shape will be a stand, but the other will be a stage. And what we'll do is we'll put a load of karate displays on there.' I found this agent that got me these guys from Chinatown in Soho who were kung fu and karate experts and they put on shows. So they put on a fantastic show. But then I thought, 'I need something more. We're gonna put on a show with some girls and get banned deliberately' because the organizers were religious fanatics.

So, I know it's terrible in today's world — you can't do this today — but we hired a dance troupe called Naughty But Nice. And what we had these girls do was a routine and dance based on our game Twister. And so we changed the name of the game from Twister to Twister: Mother of Harlots, which we then had to change back because Boots and others wouldn't take it in with that language on.

So, effectively, we were warned at the close of the very first day, 'If you put on that show tomorrow, we're going to shut you down.' Because literally every two hours, when we had the show, everyone would stop and come around our stand. People were clambering on their desks to stand up to look over the crowd to see it. We invited all the press in the next morning, we started up the show, and the power to the stand was cut. Boom. We were banned. That was it. Activision was at the show, we did a deal with them, and that was our opener.

Time Extension: Regarding Last Ninja, you've recently put up that video recently on YouTube going over its origins & inspirations. One of the interesting things you mentioned in that video is that you wanted to expand upon the ideas of Datasoft's Bruce Lee for the Atari 400 and 800. We're wondering, what were some of the main challenges in trying to accomplish that?

Cale: That was an immensely challenging situation. I loved Adventure on my 2600. I loved that and I hated text adventures. And martial arts at that time was a massive thing.

It wasn't just Bruce Lee. It was everything. Chuck Norris and all these other stars were doing martial arts movies. It was also the advent of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in comics in the early 80s as well. Ninjas were just a big thing at the time and platform games were also a big thing.

So you had Jumpman from Epyx. That was very, very big. Bruce Lee, again, was sort of a jump-and-run. And you had Miner 2049er. But what I liked about Bruce Lee was trying to have a martial arts or a fighting showdown with someone in a game. That's what they did. And I just wanted that to be the basis of where I could visualize something in 3D and have characters fighting, trying to stop you, trying to prevent you from completing your task, but while also having the same challenge [of Adventure] and trying to find things and solve puzzles where hints were given in the manuals or what have you. And that was the foundation of how The Last Ninja was set up.

Without the help of Andromeda and Istvan Bodnari and all of his team, this wouldn't have happened because their team came up with the brilliant concept of effectively having a screen of blocks or elements that you could cut out and then repeat to draw multiple high-res screens...

The challenge though was that on the Commodore you only had 64k memory, right? And so one of the biggest challenges we had is how could you make this happen. And without the help of Andromeda and Istvan Bodnari and all of his team, this wouldn't have happened because their team came up with the brilliant concept of effectively having a screen of blocks or elements that you could cut out and then repeat to draw multiple high-res screens, which was the trick as to how we could get fantastic graphics into 64k memory.

The only problem with them was they couldn't develop the game into something playable. And again, through my contact Andy Wright at Activision, they suggested, I reach out to a guy called John Twiddy. And then John took over from the Hungarians because it became clear that it wasn't going to be done in time. At that point, we scrapped almost everything. But what we did do is we looked at the integrator and John started rewriting it.

Time Extension: Another question we have is about Anthony Lee and Ben Daglish's contributions to the sound of The Last Ninja. How did they both come on board the project?

Cale: We had an approach from Anthony Lees that he was looking to do music in games, and we took him on board. And it was great. We did it straight away. We then had contracted him for so many tunes, and then we found, 'Oh, actually, it's so long to load between each level on a tape, we need some music to go with that.' And because he'd done his fixed part, again Andy Wright at Activision said, 'Speak to this guy, Ben Daglish, he'll be great.'

So we got Ben to come down and he did a load of other tunes. So we moved them around because you know, I personally think that Ben's tunes are probably some of the best tunes ever. They are up there with Martin Galway's music for Rambo: First Blood Part II on the Commodore 64.

Time Extension: Let's talk about the new Last Ninja collection. The main question we have is what made you want to put it together? Why now?

Cale: Well, it's a very good question and there are a number of parts to answer that. I think at the moment you've seen a resurgence in retro gaming. It's become a massive thing. And if you look back into the history of retro gaming, certainly on the Commodore and the Amiga formats, we were world leaders at that time in terms of games and what we've released to the market. The Last Ninja series went on to sell over 23 million copies which is incredible [Author's note: we've asked Cale for further evidence of this, as the claim seems to be widely repeated in the collection's marketing materials].

Why now? Well, as I said, retro is a massive thing for a lot of people at the moment. There's a big resurgence. And I think video game preservation is an important aspect that a lot of people are ignoring. So, for example, most products released before 2010 would disappear unless there's some form of preservation that takes place to try and protect the code and protect the history of video games. And so really at the end of the day, it's important to make sure these games are accessible and they find some sort of solution to preserve them. So, the idea of putting these games onto a Switch was very appealing to us.

Time Extension: In terms of the other games included, you've also got International Karate and Bangkok Nights in the collection. We're wondering, beyond just the commercial preservation aspect that you've already gone over, why do you feel those games kind of complement each other and belong in this collection together?

Cale: Again a great question. They complement each other because they've got one thing in common. They're all forms of martial arts, so it's a fighting pack. You're adding more value. If we were to do Last Ninja 1, 2, and 3, plus Last Ninja Remix and we were then selling a cartridge, I think it would lack a bit of depth shall we say. By adding these iconic games, we're giving more value to the consumer and more value to the fans of retro games that know these products.

Time Extension: Another bonus of this collection is that you can select different versions of each game. We're wondering, were there any versions of these games that you wanted to include here but couldn't?

Cale: We'll start with International Karate. The first version of International Karate came out on the Spectrum and it wasn't great. It was okay. It was our first attempt at a fighting game. I thought it was average at best. So I didn't want to include it in this collection. But many of our fans and backers have since said, 'You've got other Spectrum games on there, you've got to have International Karate — good or bad.'

Another version I would have loved to put on there was the ST version of International Karate, but there are huge problems in recreating an Atari ST on Switch that we just could not do that within the time frame or able to reliably know when we can finally get that done. We've got an idea as to when we can get that done, but it's something that is not in the near future. What we wanted to be able to do was be in a position with the collection to have it done on Switch, which we have, and that's why we show it on the video. And what we then do is add in people's names, because every backer gets a credit in the actual compilation of games as a thank you.

So the Atari ST version did not make it. The Atari 400 version did not make it but we can't include every single version. Because at the end of the day what we wanted to do was focus on what most people played which was Amiga, Commodore 64 and Spectrum. So the answer is quite simply, yes, we would have liked to put more formats in there, but our technology doesn't allow us to do that yet for the Atari ST. But the good news is we've made breakthroughs on the NES. So the NES versions of Last Ninja will be made because we're just very very close to that at the moment and we've got plenty of time to go on the crowdfunding.

Time Extension: One thing that grabbed a lot of people's attention was the unreleased projects that are available as part of the Diamond tier, like Last Ninja 4 and IK++. We're wondering, what can you tell us about these projects? The Last Ninja 4, I believe, was in development over many years. Am I correct?

Cale: Well, there are multiple versions of Last Ninja 4. And people can see the different two different versions the 2002 version and the 2018 version. The 2018 version is in the video and you can see how technology has changed. So the whole idea was to preserve these work-in-progress demos to show they were being worked on. What we also wanted to do was show the politics in the industry as well.

So with Last Ninja 4, we started off with Philips. They were originally doing Last Ninja 4 and that was going to originally be on PlayStation 1. They pulled out of the industry, paid us off, and we carried on working on it. Then we started looking to develop it onto PlayStation 2 and we did a deal then with Electronic Arts.

Due to politics, there was one particular format that people can find out about — because all of the communications are in [the diamond collection with redactions]. At that time, you had to have concept approvals, you had to have demos, and everything else. So it went to this format, and the platform holder said, 'No, it's not approved.' [The first-party manufacturer] wouldn't give a reason why, it was just politics. It was the only time ever in the history of video games that Electronic Arts never got concept approval as one of the largest, biggest software companies in the world. It was unbelievable.

Electronic Arts did not get Last Ninja 4 approved. It wouldn't give a reason why, it was just politics. It was the only time ever in the history of video games Electronic Arts never got concept approval as one of the largest, biggest software companies in the world. It was unbelievable.

Anyway, when this particular person left this first-party manufacturer we went in again and we did get concept approval but obviously this time Electronic Arts had moved away. They were not going to carry on publishing if they couldn't get out on all formats. So we then did a deal with Simon & Schuster. So Simon & Schuster Interactive, based in New York, signed up The Last Ninja 4 after EA. And again, like Philips, they pulled out of the industry. So we were left with Last Ninja 4 not being complete, so the project was abandoned.

We then looked at starting it again around 2016 or 2017, I believe. We were doing it on our own back. We got it all the way up to what was a fantastic demo. Everybody was very, very impressed. And there are a lot of innovative things about The Last Ninja 4 that hadn't been seen before. But we were struggling really because project costs were getting out of hand and making a game and having to fund it yourself on what would be a movie budget is a big ask.

So we were looking for partners to come in with us as we had done before, be it Ferrari Challenge and various other projects, but the retail market was changing. It was becoming digital, and anyone we spoke to just wanted the franchise outright and I wasn't willing to sell the franchise out outright to allow them to then get Last Ninja 4 as well. You can understand why people want to do that because of the cost of making these things now is huge and people want the benefit of that IP. But I felt it was something I didn't really want to do. And so the project was abandoned.

Time Extension: In regards to IK++, what can you share about that project?

Cale: So with IK++, we started working on that and we were looking at, 'Okay, we want to do a career mode, you build up your character' and it was a bit like International Tennis and various other sports titles where you train, you build up your strength, you build up your stamina, you can go into competitions, you start locally, and you build up your own dojo. You can then you can invite your friends to your dojo, train together and you can build up all these competitive teams. And it was built to try and take part in eSports which was happening at the time.

And yes, it was a concept I went through with Archer. Archer and I were working on that. Unfortunately, he got very ill. Terminally ill. And he passed. And as soon as he passed we just pulled the plug on it because it wasn't the same.

That game is almost alpha. You can play it. You can have proper fights. There's no online play on there, there's no career mode yet, but a lot of the elements of the game are already in there.

Time Extension: There are two other System 3 projects we've read about while we were looking into the company's history. It would be great if could you tell us whether these were actually being considered or not. The first is the Last Ninja Trilogy, which was apparently a 3D compilation for PS1. Is that something that existed? Or something you'd consider doing?

Cale: Yeah, so with The Last Ninja trilogy, the idea was to remake the current Last Ninja games and keep it isometric. As you can see from the campaign, most people still want Last Ninja 4 to be like that rather than a full-on 3D world. They want it to feel and look and play like Last Ninja and so that's something we're looking at potentially doing long-term. To do a full open-world in full 3D, as you know, I mean you're talking about millions and millions of pounds. I can't spend a quarter of a billion dollars on marketing and development as a small business. You know, if I had a quarter of a billion dollars I'd be sitting on the beach with my feet up, not gambling on a video game.

The idea of doing a remake of the Last Ninja games as the Last Ninja Trilogy was something we did bounce around a few times. It's just we haven't got around to planning that out. Then this came up and we thought, 'Okay, look, let's preserve the games and let's look at what people want first...

So the idea of doing a remake of the Last Ninja games as the Last Ninja Trilogy was something we did bounce around a few times. It's just we haven't got around to planning that out. Then this came up and we thought, 'Okay, look, let's preserve the games and let's look at what people want first', and then we can look at whether we're going to step back into doing a remake of the originals.

Time Extension: The second project we heard about was a fighting game called Bloodlust. Do you remember what happened with that one? Also, do you still have any of the assets or any of the code for either of these games?

Cale: Yeah, so Bloodlust was being developed by John and Steve Rowlands who had done Creatures and Mayhem in Monsterland and things like that. Both great games for the C64. They are a really brilliant set of guys who understand video games like I do. And we still have that code. So that was one of the other titles tied into the deal with Philips.

Then, after Philips terminated, we then made a deal with Atari and it became a coin-op. We had it working as a coin-op to be a rival to Killer Instinct. We were all ready to go and then Atari coin-op shut down, so that was canned as well. But again I've got playable code of that. That is something we might think about releasing at some point to people.

Time Extension: Yeah, that would be pretty amazing to see. There is some stuff out there, but we're not sure there is any actual video out there, so it would be great to see more. Obviously, with this Kickstarter, we have to imagine you knew there was going to be some demand for a Last Ninja Collection but did you realize that there'd be such a desire to play these games again? You obviously smashed your initial Kickstarter target.

Cale: Hindsight's a wonderful thing. I always believed it would do well but the skeptic in me just said, 'Be a realist'. I mean you know you're putting these wonderful titles onto the Switch, but what you don't want to do is set your ambition too high and then fail because it will kill your brand and reputation.

So there were times when I thought, 'I'm not sure I want to do this'. I'd just rather you know find a different way to do the preservation. But then a lot of people said to me, 'Look, you've got to do it.' So we ended up doing it and we put our target really low.

So I was very pleasantly surprised, shall we say. I still didn't believe we'd hit our target in 37 minutes. I was really, really surprised. There's a lot of love for the product, a lot of love for preserving those games, and there's a lot of people that really want to see those hidden gems, like you say, IK++ and Lost Ninja and everything else.

Time Extension: Thanks for your time Mark. We appreciate it!