In January 2003, legendary British game developer Jeff Minter and the Guildford-based development studio Lionhead announced Unity — a brand new game for the Nintendo GameCube that was set to combine a psychedelic virtual light synthesizer with groundbreaking shoot 'em-up mechanics.

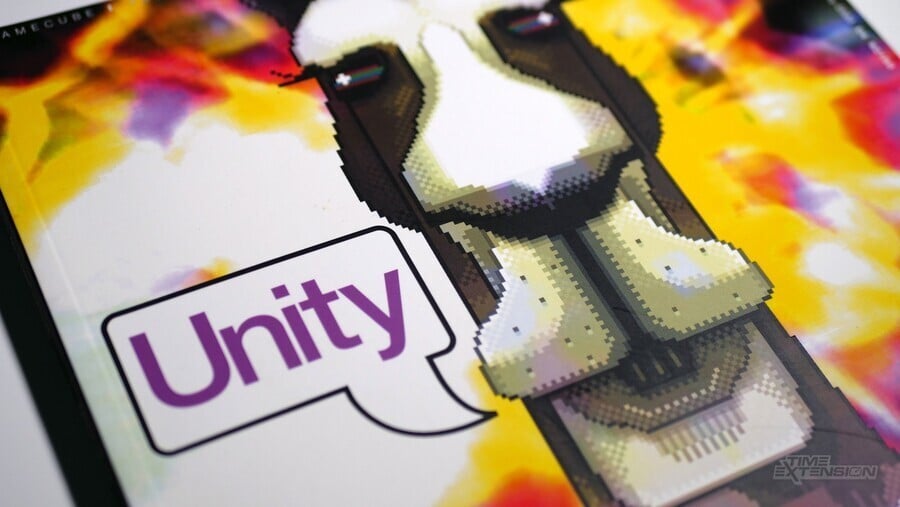

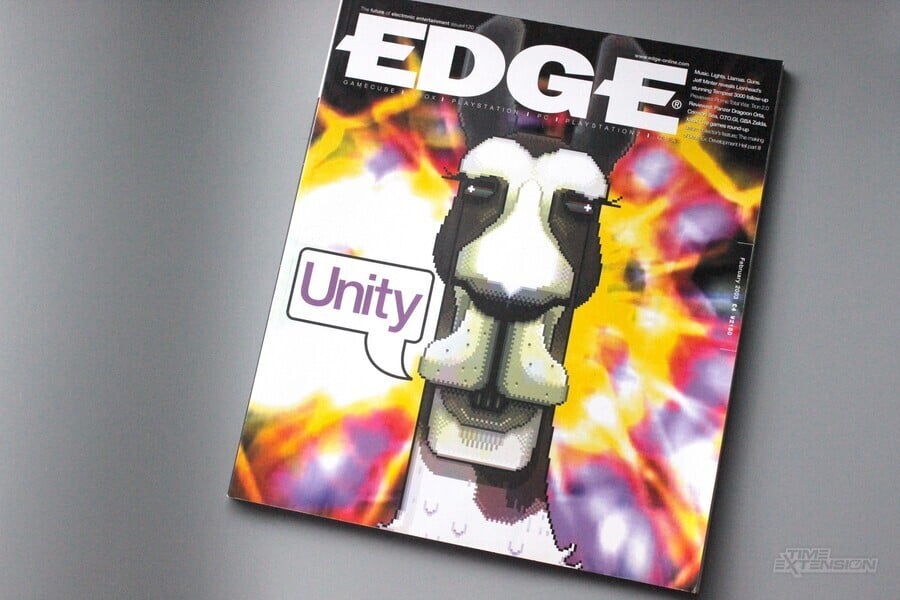

The exciting project had begun development the year prior, and would eventually go on to grace the cover of Edge Magazine in February 2003, provoking a ton of excitement from fans of Minter's earlier work including titles like Gridrunner, Attack of the Mutant Camels, and Tempest 2000.

However, after roughly two years of work, Lionhead and Minter shockingly announced in 2004 that they had decided to cancel the project, with both parties claiming at the time that it was taking much longer than they had initially anticipated to come together.

Over the years, we've always been curious to learn more about how this fascinating collaboration originally came to be and what Unity was actually like to play, so recently, we reached out to various former Lionhead employees and Minter himself (who sadly didn't reply), and scoured the internet to discover more about the cancelled project.

As we've come to understand it, the origins of Unity are rooted in a few different factors, which we'll do our best to cover here. This includes — perhaps most notably — Lionhead's decision to start partnering with a group of external satellite studios to produce games outside of the main studio.

In the early 2000s, Lionhead announced that it had begun establishing links with a small number of UK studios, including Big Blue Box and Intrepid, to work on external projects like Fable and B.C. (also unreleased), while its own teams were focused on its own individual projects internally.

Pete Hawley, a former music industry roadie turned video game producer, was the company's head of production at the time and was responsible for managing all of these different projects, but, as he tells us, he was also been given sufficient leeway in his role to be "entrepreneurial" and pitch new ideas and opportunities to the studio's leadership.

So, when James Binns (the then publisher of Edge Magazine) got in touch one day and asked him whether he would be interested in chatting with the elusive developer Jeff Minter for a potential Satellite Studio partnership, Hawley leapt at the opportunity to find out more. Hawley was already a huge fan of Minter's work, having grown up playing his games (like Revenge of the Mutant Camels) on the Commodore 64, but wasn't quite aware of what the creator had been up to ever since Tempest 2000 on the Atari Jaguar. So he emailed the creator to see about a possible collaboration and then bought a train ticket to visit his cottage in Wales and talk things over in person.

As Hawley tells Time Extension, "I jumped on a train to Wales. I had no concept of what we’d do together, but you know, Lionhead had a bit of money, we were an interesting company, and we were from the same DNA, I guess. So I went out to his cottage out in Wales, we went for a curry, and we hung out in the evening. Then he had some friends over. We were just playing insane acid techno through a projection system. We stayed up until 4 am, and then from that, we just carried on chatting. I said, ‘Lionhead will give you some money to build whatever you like.’ So that’s how we ended up on that journey with Unity."

At the time, Minter was coming off working on Tempest 3000 and VLM 2 (Virtual Light Machine 2) for VM Labs and had also been making games for the Pocket PC, but had seemingly shied away from the spotlight. The promise, however, of support from Lionhead seemed to excite the creator and soon a plan was hatched to collaborate on an ambitious arcade-style shooter for Nintendo's GameCube, with an emphasis on trippy visuals and a thumping electronic score.

At the time, Hawley was no stranger to the marriage between music and visuals, as outside of his day job at Lionhead, both he and Alex Evans (a programmer at Lionhead and the future co-founder of Media Molecule) had found themselves stumbling into an unexpected sideline doing the visuals for a bunch of artists associated with the independent record label Warp, using a piece of software Evans had created called 'bluespoon'.

As Hawley recalls, "Basically, I went around to Alex's apartment in Clapham, because we were going to music festivals together and we had very similar taste in music and he sort of said, ‘Let me show you this thing I’ve been working on.’ So he fires up his laptop, connects it to a projector, and starts playing really good electronic music through this piece of software he had developed and the software was rendering these amazing visuals in time to the tempo, volume, bass, midrange, and treble. It really blew my mind. And I was like, ‘Dude, why are you just sitting in your bedroom? This is fucking crazy.’ So I emailed Warp Records and I was like, ‘Alright, you guys have to see this."

So they turn around and there’s these two pale, nerdy, white guys with a couple of fucking laptops and they’re like ‘It was them’ and they start shaking the barriers because the sound system went off. Alex was genuinely concerned for his wellbeing. I was like, ‘Uhh, this isn’t cool’

From that initial email, the pair got to meet some of the agents who represented the acts on the label and show them bluespoon. Then, the next thing they knew, they were getting invited to do visuals for acts like Squarepusher, Aphex Twin, and Plaid, as well as events like the Sónar Festival in Barcelona — where Hawley claims both men thought they were going to be killed after the sound at the festival cut out.

"We were playing in the main DJ hall in front of 15,000 people, and I can’t remember who was playing at the time," Hawley recalls. "It might have been Carl Cox, actually, who was DJing. Alex and I were in the center of the stadium surrounded by these railings and we were up on this desk near the projection system with two laptops and we were running the whole visuals and it was pretty spectacular. And then the fucking sound system went down at 2 am, and the crowd obviously thought it was our fault, right? So they turn around and there’s these two pale, nerdy, white guys with a couple of fucking laptops and they’re like ‘It was them’ and they start shaking the barriers because the sound system went off. Alex was genuinely concerned for his wellbeing. I was like, ‘Uhh, this isn’t cool’ because there was no security, and they started shaking the barriers. Then, thankfully, the sound system came back up and everyone just started dancing again."

This pre-existing relationship with Warp isn't just a fun aside but also came to directly influence the development. Lionhead, for instance, was planning to leverage the partnership to team up with the electronic duo Plaid on the music, while development on the music visualizer for the Unity project, "VLM 3", was accelerated all of a sudden after Hawley booked Minter to do the visuals for the Warp Records Christmas Party in 2002.

On his website, Minter gives an insight into the development of the virtual light synthesizer:

"VLM 3 came about all in a rush, in just a few weeks, when my producer at Lionhead said to me one day "Jeff, I've got you booked to do the visuals at the Warp Records Christmas Rave". I kinda went "Eep!" and got my coding boots on quick smart because at that stage I had nothing that would really be usable and there wasn't that much time to prepare!

"With VLM 3 I returned to my roots, and made a completely user-performed light synthesiser, rather than the primarily audio-driven "visualizer"style of VLMs 0, 1 and 2. The Gamecube's fast 3D hardware enabled me to take effects generation out of a strictly 2D plane, as it had always been before, and enabled me to map it onto 3D environments. The major innovation of VLM 3 was that I made the lightsynth *multi-user* - for the first time a group of people could work together to orchestrate and create the display."

It was not long after the Warp Christmas Party that Unity was revealed to the public in January 2003 with a press statement on the Lionhead website.

In the statement, Lionhead co-founder Peter Molyneux claimed:

"Jeff Minter is one of the people that inspired me to get into the industry. I queued along with everyone else in the 80's to get his autograph and even considered getting a Llama! To be working with one of the founding figures of this industry is a huge honour, I am sure we'll be producing a game that is amazing and unique".

Minter, meanwhile, said about the arrangement:

"I am very happy indeed finally to be able to talk about this excellent collaboration between Llamasoft and Lionhead which will allow me to work on what is basically my dream project. The chance to undertake this work with the backing of one of the best and most respected development houses in the world, and with the guidance of some of the finest and most creative minds in the business, is perhaps the greatest opportunity I have had in my entire career, and I believe that together we can produce something truly extraordinary".

To add to the excitement, the following month, Unity appeared on the front of Edge Magazine (specifically issue #120), where it was subject to a 6-page feature (and an additional 4-page interview with Minter about his lengthy career). The message was clear: this was to be Minter's biggest, most ambitious project yet.

"Edge were obviously huge fans of Jeff Minter's work as well, and they didn’t really know where he had gone or what he was up to as well," says Hawley, explaining how the feature initially came about. "So it was a good story; ‘Molyneux and Minter’ was a good story. It was pretty early on when we met with them. They just loved the whole idea of it. I don’t know what Edge is like anymore — I don’t read print magazines much – but back then, it was all about them trying to catch things early. That was their whole thing then."

The Edge feature covered in more detail the collaboration between Lionhead and Minter and mentioned the ability for up to four users to control the separate elements of visual light synth with a GameCube controller. It also went a little into what the gameplay would be like when it was finally implemented.

Speaking about the player avatar, Minter told Edge Magazine:

"You will be embodied. Um...I don't know if it'd be right to call it a spaceship. The embodiment is something again that I intend to work on. I would like for it to be fairly unique. I don't want to give too much away, but I do like the idea that as you play, your embodiment will actually evolve, so that as each player plays the game they will eventually end up with a different embodiment. That's something I need to work on and research, but I have a pretty good idea of how that's going to work. It'll be a thirdperson view, there may be a couple of firstperson levels — as in Tempest, perhaps — but the bulk of it will be in third person."

As outlined in Edge, Lionhead didn't have any concrete end date in place for Unity's development, but Minter had essentially been given until October 2003 to get far enough for the studio to decide on its future. So over the following months, Minter would constantly keep in touch with Hawley and others at Lionhead, showing them new builds of the project. As Hawley tells us, there was very little playable presented during this time, with most of the focus being on the visualization side. Then, in September 2003, he made the personal decision to quit Lionhead for Sony, to pursue other opportunities.

In order to ensure the project had a fighting chance of being released, he elected one of his friends, an associate producer at Lionhead named Brynley Gibson, to take over the project before making his departure.

We did play it on Gamecube and it was kind of bringing those two sides together, the VLM and the gameplay. I remember there was a very crude shooter in there. You could move around 360, you were spinning around on the joystick. It was very Tempest or very Space Giraffe maybe.

Gibson says about the decision, "When I joined Lionhead, I guess I struck up quite a good friendship with Pete and we kind of bonded over similar music that we were into. I used to run club nights, I'd do visuals, I'd DJ. So when Pete was just about to leave, it was just before he left really, or in the last few months before he left, that he asked me, 'Would you be interested in this?' I obviously knew Jeff's work, because I played his games, so it was kind of cool. We were working with Warp as well because we were talking to Plaid to do music. It was like, 'Yeah, this will be super exciting to work on.'

The project continued on for another year, with Minter gradually revealing more of Unity in private demonstrations and screenshot dumps. During this time, the developer started bringing together the gameplay and the virtual light synthesizer elements.

"There was a tunnel [section]," says Gibson. "It did happen. We did play it on GameCube, and it was kind of bringing those two sides together, the VLM and the gameplay. I remember there was a very crude shooter in there. You could move around 360, you were spinning around on the joystick. It was very Tempest or very Space Giraffe, maybe. So we got the tunnel shooter, and then it was like combining it with the visualizations. So we did get to that point where the music was impacting [the surroundings], but we never got Warp Records in. There was like temp music in and I think that was like the final delivery. That was our first playable."

Former Lionhead artist Rex Crowle adds, "Unity was a progression of Tempest 2000, with shooter gameplay taking place from multiple perspectives, but with a softer, more ambient style in the environments. There wasn’t anything “retro” in how it looked, and I strangely I don’t remember any hairy mammals either! What there was, however, was a lot of focus on trying new visual techniques to visualize music in an interactive way, and I’m sure the recent release of Rez on the Dreamcast had some influence on that goal. In terms of the gameplay, I particularly remember some “trench-run” sections, flying into the screen, with the players' spacecraft hovering over the environment which was warping over time, and with the music."

From what we've been able to find out, there have been a lot of reasons given for why the project never came out, with some individuals, including Hawley, blaming his own departure from Lionhead for weakening its prospects.

"One of the problems with companies — just being objective — is if the chief sponsor leaves, generally that’s when projects can get in trouble, for want of a better word," Hawley tells us. "That’s sort of what happened. Had I stayed on and been there, I would have obviously kept pushing because it wasn’t a particularly expensive project to develop. For something like that, for something so unique, it does really need a product champion. Someone who is a real champion of this relationship or this individual game."

Gibson seems to agree with this up to a point, while also suggesting that the status of other projects within the company at the time was drawing focus away from Unity and making it difficult to support Minter as well as they would have hoped.

"Obviously, Pete was the main driving force like wanting it," says Gibson. "Could he have pulled it through? Possibly! It was probably a critical wound him going, but also, the game didn't shine. Maybe if it was given more time, it could have... but none of us on the Lionhead side were like, 'We have to make this game,' and the company was essentially struggling with all its games. Fable 1 was in the shit, The Movies was struggling to get going, and Black & White 2 was late, so I was like, 'Uhhh, should we really be making a game on the side?' It didn't make sense from the capacity we had, headspace-wise, to work on it. I do feel a bit bad in that I was very green, and maybe we could have supported Jeff better."

He continues, "I remember Jeff coming in one time with a kind of entourage as well. It was quite surreal. He was pissed, I think rightly. I do feel slightly regretful. He didn't feel like he was getting the support and that was probably true. So he had this sort of entourage with him at one point in the meeting, and this guy was like, with Peter [Molyneux] in the room, 'Don't you know who this is? This is Jeff Minter.' I was like, 'Yeah, and that's Peter Molyneux'. It was just such a weird thing to say. It was like, 'Yeah, we know, we're making a game with him."

In December 2004, the news was eventually made public that Lionhead and Llamasoft had mutually agreed to cancel the project. In a statement to the press on December 9th on the Lionhead Times website, Molyneux said the following about the project's cancellation:

"Everyone at Lionhead has the utmost respect and admiration for Jeff’s unique talents. However, we’ve both been in the industry a long time and it was becoming increasingly apparent to us that we would not be able to finish Unity in an acceptable time frame. On a personal level, I have very much enjoyed working with Jeff.”

Meanwhile, on his YakYak forums, Minter published a slightly lengthier message about the decision, revealing just how heartbreaking it was for him to abandon all those years of work:

"It’s been a horrible decision for us to have to make, but in the end we’ve had to make it. Basically, although I’ve built a shedload of stuff for Unity in the past couple of years it’s become clear that getting it all together into something that I’d be happy to call Unity and put my name to was going to take a lot of time and effort both from myself and the guys at Lionhead, and realistically it was becoming unlikely that it’d be finished in time for anyone to want to publish it on Gamecube. The alternative would be a rush job and we simply didn’t want to do that. Best to call it a day.

Obviously, I’m disappointed as I’ve put two years of my life into this and I was as desperate to play Unity as much as you were, and I understand fully just how disappointed you all are. All I can say is that I was doing this for you guys more than anyone and I’m sorry if you feel I’ve let you down. You’ve all been a wonderful source of support along the way, and even though Unity’s come to nothing I hope we can all be happy that we’ve all created something pretty much unique in this place. YakYak is something for us all to be proud of, I think.

I don’t know what happens next. Sorting all this out over the past couple of weeks has been tough and I doubt I could have got through it without the love and support of my friends. You all know who you are. But please understand if I’m a bit quiet over the next few weeks."

Following this disappointing turn of events, there was some good news that eventually followed, with Minter receiving the opportunity the following year to create a new light synth application for Microsoft called Neon, which would arrive pre-installed on every Xbox 360.

According to Minter, in a 2005 interview with The Guardian's Keith Stuart, this came about as a direct result of his work on Unity and VLM 3 for the Gamecube:

"It basically happened because a certain well-connected friend of mine really liked what we were doing here with VLM 3 on the Gamecube, and brought someone from MS here to see. He in turn got very enthusiastic and went back to MS and began bending ears. It took a fair bit of prodding and sending of demos but eventually, it progressed to the point where I got hold of a devkit. Once we had proper live 360 code running it turned from "maybe" to "definitely!".

Looking back on Unity today, it's hard not to think about what could have possibly been had it been allowed to reach its full potential, but at the very least, everyone seemed to come out of its cancellation unscathed.

Minter obviously got to salvage some of the same ideas for Neon, while Lionhead was already riding high after the release of Fable in 2004 and had two hotly anticipated titles (The Movies and Black & White 2) already on the horizon.

While Lionhead is sadly no longer around today (Microsoft eventually shut down the company in 2016), Llamasoft is fortunately still alive and kicking, with the company's latest release being 2023's Akka Arrh, a multi-platform remake of Atari's legendary scrapped arcade prototype from the 1980s.