During the mid-'80s, global arcade machine stalwart Sega found itself in an interesting situation. Since merging with Rosen Enterprises in 1965, it had already made countless strident moves in the coin-operated amusement business. The best was yet to come, too – the likes of Atari had beaten it to the punch when it came to including the latest 16-bit processes in their games, but it was Sega’s Hang-On that was about to push games into an era of graphical fidelity and fluidity that the older 8-bit machines couldn’t match, and set it on a trajectory to creating its famous 'motion simulation' beasts.

Controlled in deluxe form via the player straddling a huge plastic motorbike, Hang-On started the ‘taikan’ genre of interactive motion simulators, which would go on to include the likes of Space Harrier, OutRun, and After Burner. These legendary titles launched the careers of not only game developers like Yu Suzuki, but also many lesser-known hardware engineers and designers, such as Masaki Matsuno, You Yamaki, and Hiroshi Yagi – all working out of Sega’s ever-expanding corporate headquarters in Haneda, to the extent that their newest offices attained urban legend status as the ‘Hang-On Building’, purportedly built off the game’s profits. While this doesn't quite match up with the development and construction timelines, it would doubtless go on to make the company the new undisputed king of the arcades at that point in time.

Going hand-in-hand with this, Sega was additionally an arcade operator, with domestic locations inherited from Rosen, new openings made in the 1970s, and others purchased in the US. And yet, around the time of the release of Hang-On, it found that its Japanese facilities were suddenly under threat. Whilst the Japanese government had supported amusement parks such as Tokyo Disneyland with generous tax breaks and loans, it simultaneously looked to clamp down on less desirable coin-op arcades (or ‘game centers’, as they were becoming known). In a revision of the so-called fueihou law, it lumped them in the same morally dubious legal group as clubs, ‘soaplands’ (warning: don't look this up if you're at work), and love hotels.

The practical changes of this were not as draconian as many expected, but still had wide-reaching effects. Mirroring perceptions in many other countries, reputational problems persisted with arcades. In the face of this, Nintendo chose to abandon coin-op almost entirely, refocusing its resources on the Famicom. Meanwhile, others tried to have it both ways. Sega was now fully under the autocratic rule of coin-op veteran industry and president Hayao Nakayama, who was backed by a new majority shareholder – CSK – and its chairman Isao Okawa, who left most business matters and decisions all to him at that time.

Though Nakayama had Sega follow Nintendo down the home console route with the help of its former arcade executive Tokuzo Komai with the SG-1000 home console, he may have never heard the metaphor about having your cake and eating it. Backed with CSK’s cash and helped along by the existing success of the earlier taikan games, Nakayama led the charge on a ‘3K’ campaign – kurai (dark), kowai (scary), and kitanai (dirty) – that aimed to transform the facilities they ran, doing away with these less-desirable aspects of the operations.

"One of our first priorities when we opened new game centers was making sure there were bathrooms for both men and women," said Sega operations manager Akira Nagai on the changes (via shmuplations). "We also did things like train the employees properly, remove cigarette butts, clean ash trays, and set up smoking areas. With those efforts, I think we moved closer to being a proper service provider."

Strokes of luck in attracting more women than ever before also occurred as part of the 3K reforms. Though reasonably successful in the country since the late 1960s, the crane game was reborn in Japan by Sega with the immensely successful UFO Catcher. Medal games making use of new technology and a newly-licensed arcade version of Tetris in the iconic Aero City candy cabinets also helped. Many locations managed by Sega tried to adopt an ‘everything for everyone’ approach moving forward, favouring all.

Thanks to all of this, the ‘3K’ campaign grew to be incredibly successful. And whilst the more retrospectively recognised Sega developers continued churning out hit arcade video games to accommodate the company’s widening customer base, its unsung engineering heroes were starting to have bigger fish to fry. Off the back of the increasingly complex taikan games, they took the technology used in them and a bit of inspiration to create their largest project up to that point: the Sega Super Circuit.

Based on Mach Vision, a previous collaboration with Nissan and manga artist Makoto Kobayashi, the huge enclosure had players racing CCD camera-equipped RC cars around via modified OutRun cabinets. It very much heralded the direction that other things were moving in. As well as the advanced Galaxy Force II super deluxe machines, these debuted on location in July 1988 at Joy Square in Hamamatsu – itself a new operations frontier for Sega, as the first of what would become many suburban facilities.

Up to this point, most coin-op locations in Japan had been located in the concrete jungles of their cities. But with urban land costs rising due to the economic bubble, another wise executive poaching by Nakayama of Mitsuo Wachi from supermarket chain Ito-Yokado, and a timely proposal by operations manager Yoshihisa Nozaki, Sega had now identified locations on suburban roadside shopping parks alongside or inside other businesses as its biggest priority. Its consistently popular repertoire of games backed this up; month on month, the re-christened ‘amusement centres’ spread throughout the country, improving the company's image by placing its brand prominently in chains such as Sega World.

Veering further into family entertainment ultimately wasn’t without headaches. The late Akira Nagai, a veteran sales and operations director, is said to have found himself being scolded by Nakayama after a newly-opened Sega facility at the Alpark commercial complex in Hiroshima generated four times the expected profits. Nakayama ultimately had a point, as the extra revenue was coming from entire audience groups that it, as a company, hadn’t anticipated: parents with infants in the mornings and older children in the afternoons, then students in the evenings. Even worse, Alpark’s main attraction – a miniature train on the roof – was not Sega-made, alongside several child-friendly rides that it had no choice but to buy. Sales and R&D managers such as Takenori Ogata and Hisashi Suzuki purportedly weren’t best pleased.

Not only that, but Sega’s rivals were also on the move, running with the ideals that Nakayama had pursued as both company president and as an active leader of campaigns targeting wider change across the industry. In 1990, prolific Pac-Man and Galaxian custodian Namco would return with a vengeance; off the back of the growing ‘bigger is better’ trend in the development of machines and locations, it unveiled the ginormous 26-player Galaxian 3 interactive attraction at the Expo ‘90 event in Osaka, stealing Sega’s thunder in the same month as the Alpark facility. Galaxian and other large attractions, including a dark ride based on Tower of Druaga, would later see their first permanent installations at an actual theme park dubbed ‘Wonder Eggs’, opened in February 1992. Aspirations of a mini-Disneyland were obvious.

Fortunately, Sega hadn’t been completely resting on its laurels internally. To promote its new-style ‘amusement centres’, the short-lived ‘En-Joint Space’ term was coined, and in response to the demands of their growing customer base Sega split their engineering department into three separate teams in 1991, creating AM#4, AM#5, and AM#6. #5 was a special group strategically organised to fill the gap of creating ‘centrepiece’ attractions for large-scale locations. Having already ossified as a sub-division as far back as 1989, the personnel’s earliest work was the popular ‘Waku Waku’ traditional rocking kiddy rides.

The line began with rides based on the popular Anpanman animation and the Mitsubishi Pajero, setting themselves apart from other small children’s rides by containing monitors showing a simple sprite-based game with limited interactivity as the ride played. Though providing the basis for their design philosophy and later promoting Sega’s blue mascot wonder, these were a case of humble beginnings. The next AM5 projects – Cyber Dome, a shooting game theatre system with augmented reality elements, and CCD Cart, a physical dot eat game with multiple CCD camera-equipped carts – upped the ante considerably.

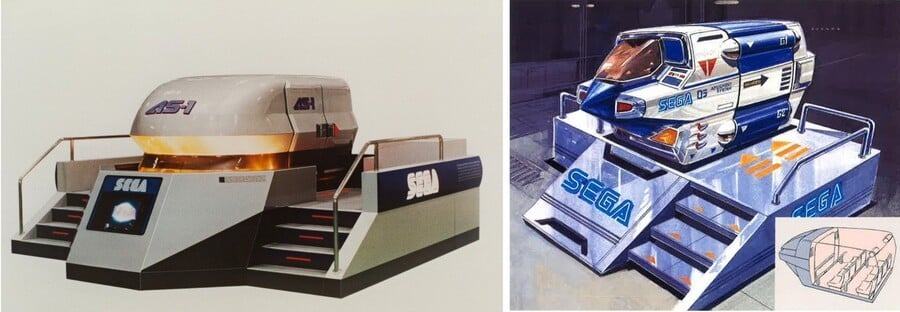

And not long after the AM4 engineers had unveiled their own biggest simulation masterpiece, the rotating marvel of the R360, it was AM5’s turn to show off what its efforts and Sega’s investment had been truly building up to. At AOU Show 1991 and in ‘En-Joint’ promotional material, the AS-1 – Advanced Simulator-1 – was revealed, looking like a Star Tours-inspired motion simulation shuttle that had landed on Earth. Over the past few years, a team of about ten early members of AM5, including aforementioned ex-AM4 designer You Yamaki, mechanical engineer Ryuichi Mori, and manager Hironao Takeda, had been working away on the project, Sega’s major calling card in the amusement attraction arena.

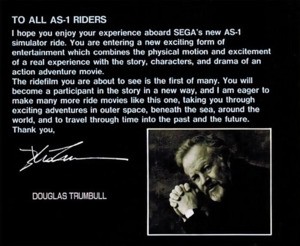

Overseeing the simulator, Yamaki had drawn up eye-catching design concepts to be shown off in flyers and booklets, Mori closed a deal with the Japanese arm of Moog Inc to manufacture a 4-axis motion base engineered to his specific requirements, and Takeda entered chance negotiations with a film director and special effects extraordinaire, the late Douglas Trumbull. His involvement, in particular, had pivotal luck; having recently stepped away from Hollywood following an exhausting battle to force the release of his final film, Trumbull looked to focus on a love of motion simulation. A well-timed contact with Sega resulted in Takeda visiting his Berkshire base in 1990 to give the prototype Back To The Future: The Ride a test drive, then commissioning his Berkshire Ridefilm team to create the first original AS-1 work.

A distinctive film was exactly what was needed for the motion simulator at this point. Although Sega had doubtless cultivated the engineering expertise, it had perhaps stepped too far ahead of what its producers could provide when it came to the visuals, with development coming to something of a stand-still as a result. Trumbull’s film filled the void perfectly and gave AM5 a valuable chance to absorb know-how for potential future in-house works; though the original plan was for Sega to send a prototype simulator to Berkshire and to receive the film and the simulator movement data in return, a last-minute safety issue with the prototype led to Berkshire sending four of their team to finish the 'ride film' in Japan.

Whilst there, Trumbull’s producers worked directly alongside Sega’s developers. Most would eventually finish and return to North America after two weeks and a satisfactory result, fully approved by Trumbull, but the AM5 team who remained now had the knowledge they needed – Not only to organise the creation of new ride films for the AS-1, but to program the movement data for them, too. Berkshire Ridefilm’s completed work, Muggo, proved a useful tool in raising the profile of the AS-1 at industry events throughout 1992, but from this point on, the focus internally was now going to be on Sega’s own projects.

Sega could now address the one thing AM5’s earliest attractions had, but the AS-1 currently lacked: interactivity. For the team, this was perhaps the most straightforward element of the entire ride, with able staff on hand who could program a rudimentary shooting game to be added to the experience. However, there was a final hurdle to overcome. Despite the technical nature of the company and its ever-expanding expertise, at the time of Muggo’s completion and preparations for the first public location tests of the AS-1, Sega still lacked the specialist personnel and equipment needed to produce a full CGI film in-house.

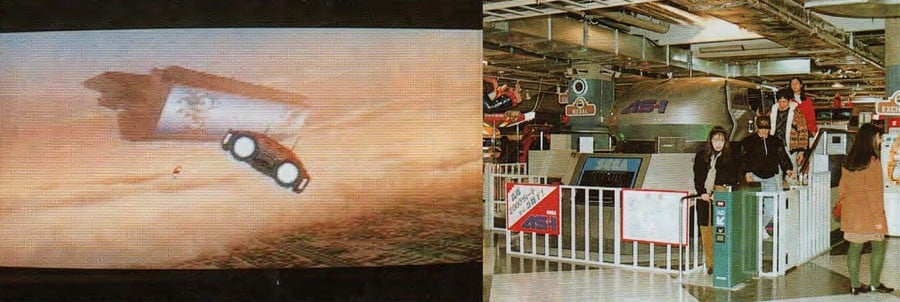

Steps would soon be taken to remedy this, but for its initial efforts, Sega opted to work with a new external production company called Graphics Technologies. Managed by a small team of young game developers with a predilection for the burgeoning art of CGI, they would first create a ride film for the AS-1’s playtests, Sega Super Coaster. Although this was a fairly primitive prototype, the test served a crucial purpose – to help prove that the simulator was truly safe. AM5’s engineers are said to have worked late throughout the tests, waiting for the phone to ring and a technician to report a fault. Their fears were unwarranted.

At the same time, internal organisation on Sega’s first original AS-1 work was beginning to bear fruit. Hiroshi Uemura, a young developer under the AM5 team and the producer of the earlier ‘Waku Waku’ kiddy ride series, had conceptualised what would become the AS-1’s signature interactive experience, Scramble Training. An eight-minute-long interactive space opera film, its premise of trainee ship pilots suddenly engaging in a real battle against enemy forces went well with the AS-1’s sleek silver shuttle design.

All that was left now was for it to be visualised by Graphics Technologies, with vice president Kenji Sasaki leading the charge. Equipped with a Silicon Graphics workstation and the PRISMS (now Houdini) software required to create CGI imagery, the animation of Scramble Training wasn’t something that came straight out of the box. Instead, Sasaki had written his own software on a Sharp X68000 to work out the trajectory of the camera and then had to feed that back into the CGI tool to generate the animated visuals. "I used a simple wireframe to create the animation, and then imported the camera coordinates for all frames into the CG tool," Sasaki-san revealed recently.

Towards the end of Scramble Training’s planned development in 1992, Sega would finally begin to cultivate its own CGI capabilities with another young developer – the now-legendary Tetsuya Mizuguchi. Having spent his initial couple of years at the company carrying out research into new technologies at AM4 and 5, he was now ready to advance to making his first works. Much to the apparent chagrin of experienced producers, Mizuguchi was granted his own sub-division, the ‘Emotion Design Lab’ under AM3, plus shiny new pieces of 3D kit – Silicon Graphics 4D35 workstations and a newly-released Indigo XS24. On these, he would devise his own motion simulation vision for the AS-1, Megalopolis: Tokyo City Battle, with fellow AM3 developer Jun Uriu and Michael Arias, a member of Trumbull’s team that had stayed behind in Japan.

Eventually completed and given a limited release the following year after early clip showcases on Bad Influence and reunion concerts for Yellow Magic Orchestra, Megalopolis contained no interactivity but may have been the most clearly defined sensory experience for the AS-1 yet – it depicted a sprawling, cyberpunk neon Tokyo in 2154, engulfed by a fight between law enforcement and an arch-terrorist.

"That was [a tough] project, because nobody knew about CGI," Mizuguchi told the now-defunct gamesTM. "'What is a digital movie?’ We learned a lot. At Sega, there was no staff like that specialised in it. All the staff at Sega, they just wanted to make a game. But this was the first visual expression project for Sega."

Off the back of its hard but worthy efforts in visual expression, Mizuguchi’s sub-team would become the first group to have built up expertise for CGI creation within Sega; the personnel were soon designated to create new AS-1 ride films and other experiments. And in the meantime, two things would result in Megalopolis and Scramble Training gaining prominence: the former’s showcase at the 1993 edition of the world-renowned SIGGRAPH conference for new CGI works, and both (but particularly the latter’s) involvement from none other than superstar and Sega superfan Michael Jackson.

Continuing a long-standing association with his favourite game-making company, Jackson agreed to become involved in the simulator between tour dates in late 1992, where he made further visits to Sega's Haneda headquarters, a noted favourite past-time of his when in Japan. Extraordinary negotiations are said to have taken place – the ‘King of Pop’ was closely involved in its creation, yet did not want to be paid for his involvement. He would, however, receive an R360 for his all-encompassing private arcade, where Sega’s machines had taken pride of place since the 1980s. Jackson would go on to appear in a pre-show for Megalopolis and starred throughout as the narrator/instructor of Scramble Training, with the title renamed and reworked with new contributions from Mizuguchi’s ‘Emotion Design Lab’ to reflect this.

By the Summer of 1993, the AS-1 was finally ready for release, with Michael Jackson in Scramble Training revealed at the Summer CES in the US and a trailer for Megalopolis making its aforementioned appearance at SIGGRAPH '93. At the end of the year, the simulators were installed in several of Sega’s newest, biggest, and brightest locations up to that point – many would receive them in Japan, but with a view to worldwide expansion, Sega VirtuaLand in the US and Sega World Bournemouth in the UK did, too. At these facilities, the AS-1 would serve its main purpose as a unique selling point and centrepiece to elevate Sega in the operations and R&D field. Though sharing space with the R360 and similarly gargantuan Virtua Formula at many of them, its enduring legacy would become something more.

Perhaps partly because Namco had beaten it to the punch and partly out of those old Disney aspirations, Sega thought bigger. The inevitable end stage of their evolved arcade concept – the ‘Amusement Theme Park’ – was entirely indoors and used early virtual reality technology to replace the grandiosity one would normally expect from a large outdoor park. The so-called ATPs could fit into smaller urban facilities where outdoor parks would not, making them an aggressive threat to the established order. "Our target is Disney," Hayao Nakayama told the New York Times in 1993.

Technology and know-how cultivated in the AS-1 were used as the starting point for many ATP attractions, including a spiritual successor, the VR-1 – one of the most advanced attempts at VR of its time and borne out of a successful partnership with the UK firm Virtuality, unlike Sega of America’s disastrous, unreleased attempt.

With the first Joypolis opening in 1994, SegaWorld London in 1996, and Sega World Sydney in 1997, Sega had managed to become as globally active in just three years as the Disney theme parks had been after thirty. Plans were underway for over 100 more by the 2000s; equipped with rides as innovative and sophisticated as the AS-1, they were thought to be a credible threat to the traditional theme park.

And though the prospect of a Disney-backed US Joypolis was initially on the cards, the egos of the House of Mouse opted to strike out alone, with its Imagineers emulating many of Sega’s attractions for its own DisneyQuest template – creating a feedback loop, as Sega itself had sent its engineers out to numerous US theme parks in the early '90s. Sega, meanwhile, embarked on the GameWorks project with two more western entertainment giants; MCA/Universal and DreamWorks. Yet this would not feature the likes of the AS-1, favouring new attractions by another famous collaborator, Steven Spielberg.

Ultimately, however, all of these efforts would not deliver on their promises, with business models soon proving uneconomic and wider corporate problems spelling out the demise of the parks that did open. Further AS-1 films never came either, despite a ‘Sonic Ride’ prototype thought to be intended for them. Still, tenaciously, a few Joypolis locations remain to this day, including the Tokyo flagship opened in 1996 – even with their original intent long lost, their AS-1 simulators contained long decommissioned, and the likes of Scramble Training only viewable now by certain miraculous preservation efforts, these remaining locations are indebted to those original engineers of AM5, some of whom still remain involved today.

Outside of the technological innovations of the simulator that enabled the likes of Tokyo Joypolis to continue operating into the 2020s, the AS-1’s software works launched numerous careers. The creators of its two most prominent ride films in particular – the aforementioned Kenji Sasaki and Tetsuya Mizuguchi – met after working on their projects for it as young, inexperienced developers. The groundwork was laid for them here to then come together as director and producer for the creation of Sega Rally Championship, the video game on which they would truly make their names, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Many now know Sasaki as something of an arcade legend, responsible for scores of Sega’s best-loved racing games and more. Meanwhile, Mizuguchi goes without saying as one of the most world-renowned auteurs in gaming. And again, just as Tokyo Joypolis rumbles on, Sega alumni that got their start on the AS-1 like Sasaki even now get to exert influence on gaming, both via his continuing independent work for Sega Amusements International on its new Drone Racing Genesis game, and from new generations of developers reworking his old classics for today in the form of C-Smash VRS and Over Jump. "I am happy that I am still active as I was then," he says.

Culturally, Sega’s AS-1 films – particularly Megalopolis – left an impression that lingered longer than most would first think. Thanks in part to its inclusion in SIGGRAPH '93, not only was footage from Megalopolis then used in influential CGI art-film instalment The Gate to the Mind's Eye, but French director Luc Besson became another who is said to have seen the film – and also wanted to ride an AS-1 as a guest at Sega's headquarters. A few years on from this, he would create the epic taxi chase scene for his classic sci-fi adventure the Fifth Element – recently combined with another Sega classic as well – and when comparing them, it is not hard to see where he most likely got some of the inspiration from.

In the end, Sega’s influential stay in the theme park industry was brief but potent, vividly demonstrating the need for interactivity in future theme park attractions. For all its lesser historical infamy, and the swift fall of many of the business endeavours that Sega touted in amusement operations, the AS-1 deserves to be held up as a talisman – both for that innovative spirit of blending the physical, virtual and interactive together, but also for a company and its creators in their exorbitant, booming and ultimately fearless prime.

“From the end of the 1980s, I was making prototypes for the AS-1 and I've had the opportunity to do location demonstrations… It's a fond memory. This is my memorable first job at Sega.” concludes Kenji Sasaki.